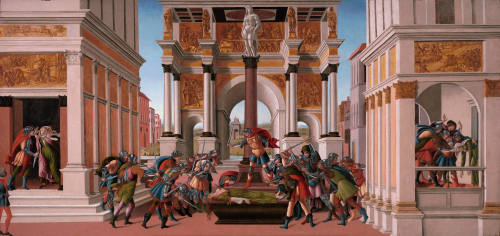

The Story of Lucretia

painter

Sandro Botticelli

(Florence, 1444 or 1445 - 1510, Florence)

Dateabout 1500

Place MadeFlorence, Tuscany, Italy, Europe

MediumTempera and oil on panel

Dimensions83.8 x 176.8 cm (33 x 69 5/8 in.)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineIsabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Accession numberP16e20

eMuseum ID723125

EmbARK ObjectID10986

TMS Source ID244

Last Updated10/29/24

Status

Not on viewWeb CommentaryAccording to legend, Lucretia’s brutal rape and tragic suicide precipitated the foundation of the Roman Republic. Botticelli distilled Lucretia’s shocking story into three episodes, beginning at the left. Beautiful and chaste, she attracts the unwanted attention of the king’s son, who threatens Lucretia at knifepoint with sexual assault or a dishonorable death. Raped, she collapses in shame before her outraged family, depicted at the right, and ultimately commits suicide.

The public display of Lucretia’s corpse galvanized the rebels led by Brutus. Brandishing a sword, he rallies an army to overthrow the corrupt regime. The architectural setting of the rebellion remakes the past into the present, likening ancient Rome to Renaissance Florence. Botticelli transformed Lucretia’s body—dagger embedded in her chest—into an emblem of liberty, like the biblical hero and Florentine icon David, who stands on the column above her.

Botticelli painted this work to decorate a palace in Florence in connection with a marriage. Perhaps with this in mind, Isabella Gardner placed a cassone, or wedding chest, beneath it. The Renaissance bride filled her cassone with prized and personal belongings—linens, undergarments, jewelry, cosmetics, and sewing implements. Mrs. Gardner draped a velvet textile (now a reproduction) over this cassone and put inside other textiles and an eighteenth-century guitar.

Botticelli painted this work to decorate a palace in Florence in connection with a marriage. Perhaps with this in mind, Isabella Gardner placed a cassone, or wedding chest, beneath it. The Renaissance bride filled her cassone with prized and personal belongings—linens, undergarments, jewelry, cosmetics, and sewing implements. Mrs. Gardner draped a velvet textile (now a reproduction) over this cassone and put inside other textiles and an eighteenth-century guitar.

BibliographyNotes

Bernard Berenson. "Les Peintures Italiennes de New York et de Boston ." Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1896), pp. 195, 206-07, ill.

Art Exhibition: Mrs. John L. Gardner, 152 Beacon St., Boston. Exh. cat. (Boston, 1899), p. 7, no. 13.

Catalogue. Fenway Court. (Boston, 1903), p. 10.

William Rankin. "Cassone Fronts in American Collections." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 9 (1906), p. 288.

Wilhelm Bode. Sandro Botticelli (London, 1925), pp. 96, 128-29, 141.

Philip Hendy. Catalogue of Exhibited Paintings and Drawings (Boston, 1931), pp. 66-69.

Gilbert Wendel Longstreet and Morris Carter. General Catalogue (Boston, 1935), p. 113.

Morris Carter. "Mrs. Gardner & The Treasures of Fenway Court" in Alfred M. Frankfurter (ed.). The Gardner Collection (New York, 1946), pp. 6, 56.

Stuart Preston. "The Tragedy of Lucretia" in Alfred M. Frankfurter (ed.). The Gardner Collection (New York, 1946), pp. 22-23, ills.

Corinna Lindon Smith. Interesting People (Norman, Oklahoma, 1962), p. 158

Guy Walton. "The Lucretia Panel in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston" in Essays in Honor of Walter Friedlaender (New York: The Institute of Fine Art, 1965), pp. 177-86.

“Notes, Records, Comments.” Gardner Museum Calendar of Events 8, no. 44 (4 Jul. 1965), pp. 2-3. (excerpting Guy Walton, pp. 177-86)

George L. Stout. Treasures from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1969), pp. 120-21.

Philip Hendy. European and American Paintings in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1974), pp. 38-41.

Ronald Lightbown: Botticelli: Complete Catalogue, Vol. II (Berkeley, 1978), pp. 101-103, no. B91.

Ellen Callmann. Beyond Nobility: Art for the Private Citizen in the Early Renaissance. Exh. cat. (Allentown: Allentown Art Museum, 1980), pp. xix-xx, ill.

Herbert P. Horne. Botticelli: Painter of Florence (Princeton, 1980), pp. 285-86.

Rollin van N. Hadley. Museums Discovered: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1981), pp. 48-49.

Rollin van N. Hadley (ed.). The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner 1887-1924 (Boston, 1987),pp. 35, 39-40, 176, 294, 487.

Ronald Lightbown. Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work (New York, 1989), pp. 264-269.

Hilliard Goldfarb. Imaging the Self in Renaissance Italy. Exploring Treasures in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum III. Exh. cat. (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1992), pp. 29-31.

Hilliard Goldfarb and Susan Sinclair. Isabella Stewart Gardner: Woman and the Myth. Exh. cat. (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1994), 19-20.

Anne B. Barriault. Spalliera Paintings of Renaissance Tuscany: Fables of Poets for Patrician Homes (University Park, Pennsylvania, 1994), pp. 154, 181, no. 13.2.

Jonathan Nelson. "Filippino Lippi's 'Allegory of Discord': A Warning about Families and Politics." Gazette des Beaux-Arts (Dec. 1996), pp. 237-52.

Laurence Kanter. "Sandro Botticelli, The Tragedy of Lucretia" in Hilliard Goldfarb et al. Italian Paintings and Drawings Before 1800 in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Unpublished manuscript. (Boston, 1996-2000).

Hilliard Goldfarb et al. Botticelli’s Witness: Changing Style in a Changing Florence. Exh. cat. (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1997), pp. 56-60.

Alexandra Grömling and Tilman Lingesleben. Alessandro Botticelli: 1444/45-1510. (Köln, 1998), pp. 110-13, no. 125.

Cristelle L. Baskins. "Lucretia: Dangerous Familiars" in Cassone Painting, Humanism, and Gender in Early Modern Italy (Cambridge, 1998), pp.128-59, fig. 54.

Alan Chong et al. (eds.) Eye of the Beholder: Masterpieces from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 2003), pp. 68-69.

Pierluigi De Vecchi. "Movement, Action and Expression in the Work of Sandro Botticelli" in Botticelli and Filippino: Passion and Grace in Fifteenth-Century Painting. Exh. cat. (Paris: Musée du Luxembourg; Florence: Palazzo Strozzi, 2004), pp. 42-43, fig. 3.

Alessandro Cecchi. Botticelli (Milan, 2005), pp. 341-45.

Cynthia Saltzman. Old Masters, New World: America’s Raid on Europe’s Great Pictures (New York: Penguin Books, 2008), pp. 45, 57, 67, 69.

Jacqueline Marie Mussacchio. Art, Marriage, and Family in the Florentine Renaissance Palace (New Haven and London, 2008), pp. 239-41, fig. 253.

Andrea Di Lorenzo. Botticelli: Nell Collezioni Lombarde. Exh. cat. (Milan: Museo Poldi Pezzoli, 2010), pp. 74-79, ill.

Jeremy Howard (ed.). Colnaghi: The History (London, 2010), p. 27, fig. 3.

Maria Cristina Rodeschini Galati. Sandro Boticelli: 'persona sofistica' : i dipinti dell'Accademia Carrara (Bergamo, 2012), p. 33, fig. 5.

Irene Mariani. "The Vespucci Family and Sandro Botticelli: Friendship and Patronage in the Gonfalone Unicorno" in Gert Jan van der Sman and Irene Mariani (eds.). Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510): Artist and Entrepreneur in Renaissance Florence (Florence, 2015), pp. 210-11, fig. 6.

Carl Brandon Strehlke. "Bernard and Mary Berenson Collect: Pictures Come to I Tatti" in Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls. The Bernard and Mary Berenson Collection of European Paintings at Villa I Tatti (Milan, 2015), pp. 20, 22, 42.

Jeremy Howard. "From print selling to picture dealings: Colnaghi 1760-2002," "The Colnaghi Archive: A general introduction" and "Colnaghi, Bernard Berenson and Mrs. Gardner's first Botticelli" in Colnaghi. Colnaghi Past, Present, and Future: An Anthology (London, 2016), pp. 4, 7-8, 20-26, 278, fig. 7.

Oliver Tostmann. "Bernard Berenson and America's Discovery of Sandro Botticelli" in Mark Evans et al. Botticelli Reimagined. Exh. cat. (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2016), pp. 108-109, fig. 56.

Nathaniel Silver. "'She triumphed in the face of fierce competition' Nathaniel Silver on Isabella Stewart Gardner." Apollo Magazine (March 2016), p. 44.

Liliana Beatrice Ricciardi. Le rose del Piacere: da Zeus a Sperelli violenza e seduzione (Modena: Il Bulino edizioni d'arte, 2018), p. 50, fig. 37.

M. Cristina Rodeschini et al. Le storie di Botticelli: tra Boston e Bergamo. Exh. cat. (Milan: Officina Libraria, 2018), pp. 13, 15, 20-22, 27-36, 48-49, 54, 116-121; ill. pp. 12, 20 (fig. 7), 26, 29 (fig. 2), 117-118, 121; cat. no. III.2 pp. 105-107.

Giovanni Valagussa et al. Accademia Carrara di Bergamo: dipinti del Trecento e del Quatrocento: catalogo completo (Milan: Officina libraria, 2018), pp. 97-100.

Jeremy Howard. "Selling Botticelli to America: Colnaghi, Bernard Berenson and the Sale of the Madonna of the Eucharist to Isabella Stewart Gardner." Colnaghi Studies 4 (March 2019), pp. 137-140, 146, 153, ill. pp. 138 fig. 1, 166.x

Alison Wright. Frame Work: Honour and Ornament in Italian Renaissance Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), pp. 58-59, fig. 35.

Anne B. Barriault. "Battening spalliera paintings: reflections on twenty-five years of research." The Burlington Magazine (Jan. 2020), pp. 37-45, fig. 2.

Jeremy Howard. "Botticelli: Heroines and Heros Review". The Burlington Magazine (Oct. 2020), pp.902-903, fig. 3.

Henri De Riedmatten. Le Suicide De Lucrèce: Èros et politique à la Renaissance. (Actes Sud, 2022), pp. 49 (fig. 2), 65 (fig. 13), 68 (fig. 15).

Furio Rinaldi. Botticelli Drawings. Exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 2023), p.186, fig. 35.1.

ProvenanceNotesProbably commissioned for Giovanni di Guidantonio Vespucci (1476–1534) and Namicina di Benedetto Nerli at Casa Vespucci, Via de' Servi, Florence, about 1500. (as part of a spalliere)

Purchased by the patrician Piero Salviati in 1533. (as part of the purchase of Casa Vespucci)

By descent to Lucrezia Salviati and her husband, the musician, writer and scientist Giovanni de Bardi di Vernio, after 1568 until about 1584.

Collection of Bertram Ashburnham, 5th Earl of Ashburnham (1840–1913), Ashburnham Place, Sussex by 1894.

Purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner from Bertram Ashburnham, London for £3400 on 19 December 1894 through the American art historian Bernard Berenson (1865–1959).

Purchased by the patrician Piero Salviati in 1533. (as part of the purchase of Casa Vespucci)

By descent to Lucrezia Salviati and her husband, the musician, writer and scientist Giovanni de Bardi di Vernio, after 1568 until about 1584.

Collection of Bertram Ashburnham, 5th Earl of Ashburnham (1840–1913), Ashburnham Place, Sussex by 1894.

Purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner from Bertram Ashburnham, London for £3400 on 19 December 1894 through the American art historian Bernard Berenson (1865–1959).