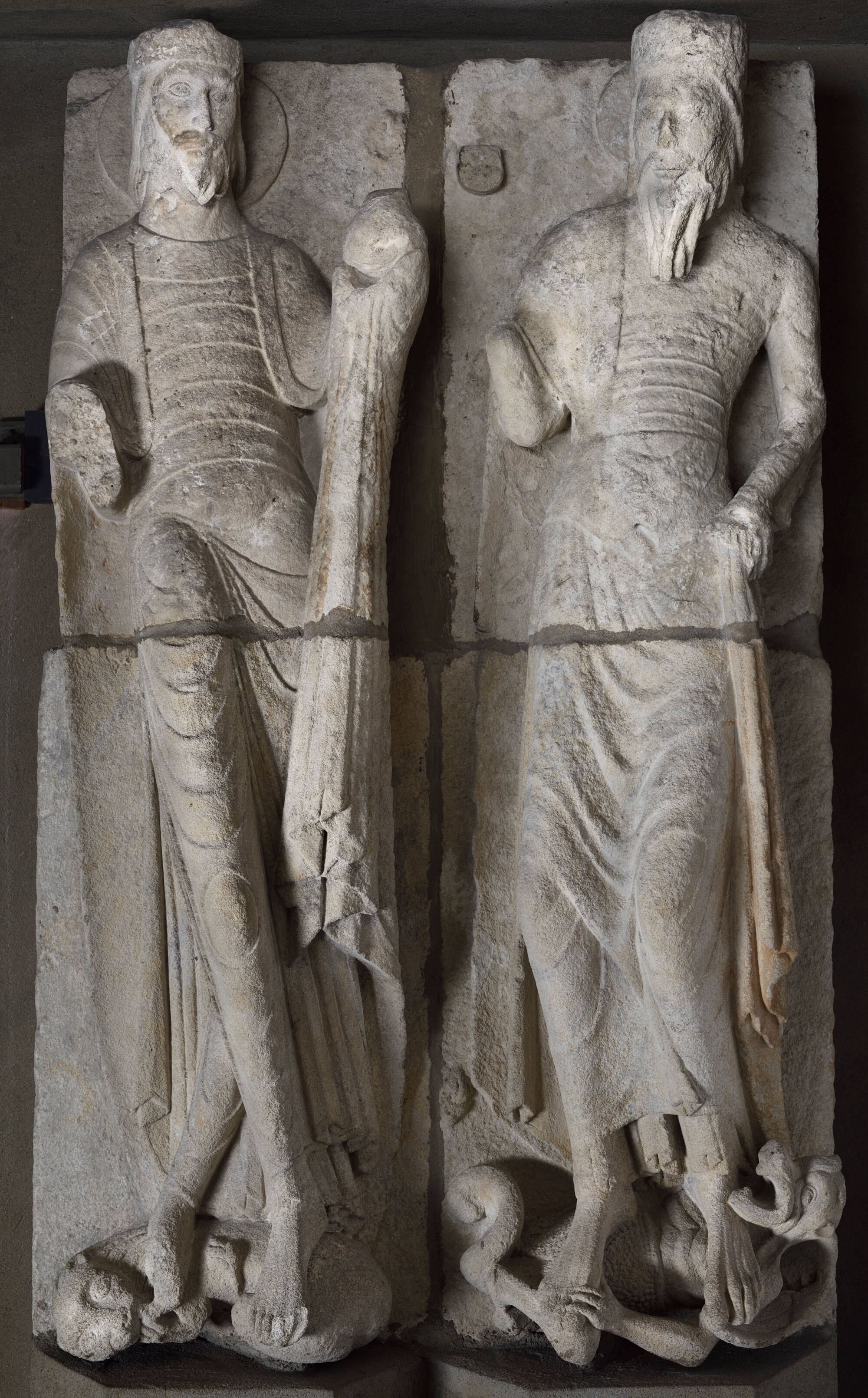

Two Elders of the Apocalypse

maker

Unknown

Datemid 12th century

Place MadePathenay, Poitou-Charentes, France, Europe

MediumLimestone

Dimensions77.4 x 99 x 25.9 cm (30 1/2 x 39 x 10 3/16 in.)

ClassificationsArchitectural Elements

Credit LineIsabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Accession numberS7n2

eMuseum ID719799

EmbARK ObjectID11360

TMS Source ID584

Last Updated8/14/24

Status

Not on viewWeb CommentaryMedieval art occupied only the margins of American collecting taste at the turn of the nineteenth century. When Mrs. Gardner acquired these three sculptures in 1916, they were among the most impressive examples of monumental medieval sculpture yet seen in America. The acquisition helped establish Gardner at the forefront of medieval collecting, blazing a trail that William Randolph Hearst, Raymond Pitcairn, and John D. Rockefeller Jr. would soon follow.

Often compared to statues at Chartres, these sculptures from Parthenay (a town in Poitou) possess qualities that define twelfth-century religious art. Static yet vividly compelling, the monumental figures express the timelessness of Christian theology while evoking the realism of everyday life. Facial expressions are minimized, lending an imposing, otherworldly allure, yet the soft modeling of the lips, eyebrows and curling locks of hair suggests real human qualities. Their stately character befits the crowned personages portrayed: Christ, on his triumphant entry into Jerusalem, and the Elders witnessing the Revelations of the Apocalypse.

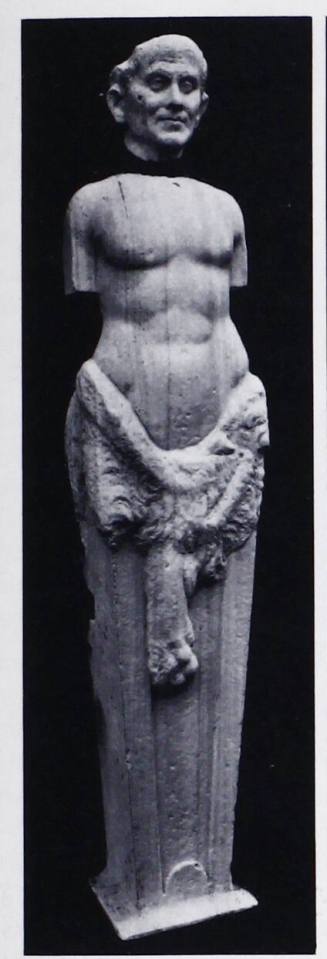

Controversy, too, lent the sculptures a certain notoriety. All came from the facade of a feudal lord’s courtly church, Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre, a site long important to French patrimony. Their acquisition by no less a connoisseur than Mrs. Gardner launched a frenzy of interest in Romanesque Parthenay. Soon more sculptures flooded the market, including several removed illegally as well as some outright forgeries. Mrs. Gardner’s own dealer, Georges Demotte, was pursued in the Paris courts, where eventually a sculptor in Demotte’s service admitted embellishing several unspecified statues. Before the affair could be resolved, the sculptor was found dead, the victim of an apparent suicide; soon afterward, Demotte, too, was mysteriously killed in a hunting accident. These bizarre episodes caused suspicions about the Gardner sculptures to linger until the 1940s, when scientific analysis finally demonstrated that the lower halves of the Elders were forgeries, while the magnificent busts and the entire Entry into Jerusalem relief were authentic. Today there is no hesitation in counting these works among the most important Romanesque sculptures in America. They speak as much to the excellence of medieval carvers as to modern passions for the art of the Middle Ages.

Source: Robert Maxwell, "Christ Entering Jerusalem, Two Elders of the Apocalypse," in Eye of the Beholder, edited by Alan Chong et al. (Boston: ISGM and Beacon Press, 2003): 21.

Often compared to statues at Chartres, these sculptures from Parthenay (a town in Poitou) possess qualities that define twelfth-century religious art. Static yet vividly compelling, the monumental figures express the timelessness of Christian theology while evoking the realism of everyday life. Facial expressions are minimized, lending an imposing, otherworldly allure, yet the soft modeling of the lips, eyebrows and curling locks of hair suggests real human qualities. Their stately character befits the crowned personages portrayed: Christ, on his triumphant entry into Jerusalem, and the Elders witnessing the Revelations of the Apocalypse.

Controversy, too, lent the sculptures a certain notoriety. All came from the facade of a feudal lord’s courtly church, Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre, a site long important to French patrimony. Their acquisition by no less a connoisseur than Mrs. Gardner launched a frenzy of interest in Romanesque Parthenay. Soon more sculptures flooded the market, including several removed illegally as well as some outright forgeries. Mrs. Gardner’s own dealer, Georges Demotte, was pursued in the Paris courts, where eventually a sculptor in Demotte’s service admitted embellishing several unspecified statues. Before the affair could be resolved, the sculptor was found dead, the victim of an apparent suicide; soon afterward, Demotte, too, was mysteriously killed in a hunting accident. These bizarre episodes caused suspicions about the Gardner sculptures to linger until the 1940s, when scientific analysis finally demonstrated that the lower halves of the Elders were forgeries, while the magnificent busts and the entire Entry into Jerusalem relief were authentic. Today there is no hesitation in counting these works among the most important Romanesque sculptures in America. They speak as much to the excellence of medieval carvers as to modern passions for the art of the Middle Ages.

Source: Robert Maxwell, "Christ Entering Jerusalem, Two Elders of the Apocalypse," in Eye of the Beholder, edited by Alan Chong et al. (Boston: ISGM and Beacon Press, 2003): 21.

BibliographyNotesC.H. Arnauld. Monuments religieux, militaires et civils du Poitou (Niort, 1843), pp. 95-98. (as beginning of the 12th century)

C. Auber. "Notice sur l'église de la Couldre à Parthenay." Bulletin du Comité historique des arts et monuments (1849), pp. 125-128.

Bélisaire Ledain. La Gâtine Historique et Monumentale (Paris, 1876), pp. 72-82, figs. 24-25. (as "Elders of the Apocalypse")

"Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre." Congrès archéologique de France, Poitiers (Paris, 1903), pp. 46-47, ill. (as "crowned and haloed persons")

André Michel. "Les Bas-Reliefs de Notre-Dame de la Couldre au Musée du Louvre." Les Musées de France (1914), p. 67. (briefly mentions the two Kings not in the Louvre's collection; Mrs. Gardner kept this magazine in a folder on top of the desk in the Tapestry Room)

Andre Michel. "Les sculptures de l'ancienne façade de Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre à Parthenay." Monuments et Mémories (1916), pp. 179-95, fig. 1. (as "as figure in high relief;" middle of the 12th century, after 1135; pictured with legs for the first time)

Raimond van Marle. "Twelfth Century French Sculpture in America." Art in America and Elsewhere (1921), pp. 12-13. (as "crowned and bearded statues;" 2nd half of the 12th century)

Georges Turpin. "L'église Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre à Parthenay et ses sculptures." Bulletin de la Société historique et scientifique des Deux-Sèvres (1922), pp. 79-91. (as "Kings")

Arthur Kingsley Porter. Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads (Boston, 1923), pp. 334-36. (as "Elders of the Apocalypse;" perhaps by the unknown creator of Chadennac's simillar sculpture, about 1140)

"Statues Sold to 'Madame Gardner': Genuineness of Parthenay Pieces now under Fire." Boston Herald (Boston), 25 May 1923. (the legs as potentially forgeries; or constructed from fragments found later on the spot; this article and those that follow discuss a minor scandal relating to doubts in the Parthenay sculptures' authenticy. For more information, please see Meryle Secrest's publication referenced below.)

Edwin L. James. "Sold Fakes to Mrs. Gardner: Parisian says he stuck many Americans and Metropolitan Museum." Boston Herald (Boston), 2 Jun. 1923. (one king as "entirely fabricated;" the other as a forgery but the bust as authentic)

A.J. Philpott. "Bostonians not 'Stung' on Art: Gothic Sculptures here Declared Genuine." Boston Sunday Globe (Boston), 3 Jun. 1923. (as genuinely medieval)

"Victim of Sharpness." Boston Sunday Advertiser (Boston), 3 June 1923. (as likely forgeries)

"Mrs. Gardner will Sift 'Fake' Story: Not Satisfied she was Duped in Purchase of Statues." Boston Sunday Herald (Boston), 3 Jun. 1923.

A.P. "Repeats Gardner Statue is a Fake: De Motte Testifies at Paris Inquiry." Boston Herald (Boston), 20 Jun. 1923.

"Declares he Sold 'Kings' to Mrs. Gardner." Boston Sunday Herald (Boston), Jun. 24 1923.

Paul Deschamps. La sculpture française à l'époque romane (Paris, 1930), p. 72.

Erwin. O. Christensen. Account of Two Reliefs from Parthenay in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Unpublished manuscript. (Boston, 1931), pp. 1-5. (as "Two Elders of the Apocalypse;" French, 12th century; lower left portion as restored, entire right portion as restored)

Gilbert Wendel Longstreet and Morris Carter. General Catalogue (Boston, 1935), pp. 49-50. (the lower halves as forgeries)

James J. Rorimer. "The Restored Twentieth Century Parthenay Sculptures." Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts (1942), pp. 123-30, fig. 1.

René Crozet. L'art roman en Poitou (Paris, 1948), p. 224.

M. Aubert et al. Description raisonnée des sculptures du Moyen Age, de la Renaissance et des temps modernes (Paris, 1950), pp. 51-53.

Guy Isnard. Faux et imitations dans l'Art (Paris, 1959), pp. 143-46.

William N. Mason. “Notes, Records, Comments.” Gardner Museum Calendar of Events 6, no. 21 (20 Jan. 1963), p. 2.

George L. Stout. Treasures from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1969), p. 68. (as by 1135)

Walter Cahn. "Romanesque Sculpture in American Collections. IV. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston." Gesta (1969), pp. 47-49, no. 1a. (as "Two Kings;" French, middle of the 12th century)

Cornelius C. Vermeule III et al. Sculpture in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1977), pp. 75-78, no. 106.

Walter Cahn. "Medieval Sculpture" in James Thomas Herbert Baily (ed.). The Connoisseur: An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors, "Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum" (London, 1978), p. 21.

Rollin van N. Hadley (ed.). The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner 1887-1924 (Boston, 1987), pp. 524-25, 528-39, 614, 618, 620.

Paul Williamson et al. Northern Gothic Sculpture, 1200-1450 (London, 1988), pp. 19-20.

Robert A. Maxwell. Romanesque Parthenay: Art and Urbanism in Fedual Aquitaine. PhD. diss. (New Haven: Yale University, 1999), passim.

Alan Chong and Giovanna De Appolonia. The Art of the Cross: Medieval and Renaissance Piety in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Exh. cat. (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2001), p. 25.

Alan Chong et al. (eds.) Eye of the Beholder: Masterpieces from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 2003), p. 21, ill. (as "Two Elders of the Apocalypse;" mid 12th century)

Meryle Secrest. Duveen: A Life in Art (New York, 2004), pp. 207-223.

Robert A. Maxwell et al. "The Dispersed Sculpture of Parthenay and the Contributions of Nuclear Science." Jounral of the Society for Medieval Archaeology (2005), pp. 247-80, no. 7, fig. 7.

Charles T. Little (ed.). Set in Stone: The Face in Medieval Sculpture. Exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007), pp. 86-87, 189.

Robert A. Maxwell. The Art of Medieval Urbanism: Parthenay in Romanesque Aquitaine (Philadelphia, 2007), pp. 147, 222-23, 229, 237, 244, 249, fig. 222.

Robert A. Maxwell. "Accounting for taste: American collectors and twelfth-century French sculpture." Journal of the History of Collections (Feb. 2015), pp. 1-12, fig. 4. (dated about 1160s-1170s with restoration)

C. Auber. "Notice sur l'église de la Couldre à Parthenay." Bulletin du Comité historique des arts et monuments (1849), pp. 125-128.

Bélisaire Ledain. La Gâtine Historique et Monumentale (Paris, 1876), pp. 72-82, figs. 24-25. (as "Elders of the Apocalypse")

"Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre." Congrès archéologique de France, Poitiers (Paris, 1903), pp. 46-47, ill. (as "crowned and haloed persons")

André Michel. "Les Bas-Reliefs de Notre-Dame de la Couldre au Musée du Louvre." Les Musées de France (1914), p. 67. (briefly mentions the two Kings not in the Louvre's collection; Mrs. Gardner kept this magazine in a folder on top of the desk in the Tapestry Room)

Andre Michel. "Les sculptures de l'ancienne façade de Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre à Parthenay." Monuments et Mémories (1916), pp. 179-95, fig. 1. (as "as figure in high relief;" middle of the 12th century, after 1135; pictured with legs for the first time)

Raimond van Marle. "Twelfth Century French Sculpture in America." Art in America and Elsewhere (1921), pp. 12-13. (as "crowned and bearded statues;" 2nd half of the 12th century)

Georges Turpin. "L'église Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre à Parthenay et ses sculptures." Bulletin de la Société historique et scientifique des Deux-Sèvres (1922), pp. 79-91. (as "Kings")

Arthur Kingsley Porter. Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads (Boston, 1923), pp. 334-36. (as "Elders of the Apocalypse;" perhaps by the unknown creator of Chadennac's simillar sculpture, about 1140)

"Statues Sold to 'Madame Gardner': Genuineness of Parthenay Pieces now under Fire." Boston Herald (Boston), 25 May 1923. (the legs as potentially forgeries; or constructed from fragments found later on the spot; this article and those that follow discuss a minor scandal relating to doubts in the Parthenay sculptures' authenticy. For more information, please see Meryle Secrest's publication referenced below.)

Edwin L. James. "Sold Fakes to Mrs. Gardner: Parisian says he stuck many Americans and Metropolitan Museum." Boston Herald (Boston), 2 Jun. 1923. (one king as "entirely fabricated;" the other as a forgery but the bust as authentic)

A.J. Philpott. "Bostonians not 'Stung' on Art: Gothic Sculptures here Declared Genuine." Boston Sunday Globe (Boston), 3 Jun. 1923. (as genuinely medieval)

"Victim of Sharpness." Boston Sunday Advertiser (Boston), 3 June 1923. (as likely forgeries)

"Mrs. Gardner will Sift 'Fake' Story: Not Satisfied she was Duped in Purchase of Statues." Boston Sunday Herald (Boston), 3 Jun. 1923.

A.P. "Repeats Gardner Statue is a Fake: De Motte Testifies at Paris Inquiry." Boston Herald (Boston), 20 Jun. 1923.

"Declares he Sold 'Kings' to Mrs. Gardner." Boston Sunday Herald (Boston), Jun. 24 1923.

Paul Deschamps. La sculpture française à l'époque romane (Paris, 1930), p. 72.

Erwin. O. Christensen. Account of Two Reliefs from Parthenay in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Unpublished manuscript. (Boston, 1931), pp. 1-5. (as "Two Elders of the Apocalypse;" French, 12th century; lower left portion as restored, entire right portion as restored)

Gilbert Wendel Longstreet and Morris Carter. General Catalogue (Boston, 1935), pp. 49-50. (the lower halves as forgeries)

James J. Rorimer. "The Restored Twentieth Century Parthenay Sculptures." Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts (1942), pp. 123-30, fig. 1.

René Crozet. L'art roman en Poitou (Paris, 1948), p. 224.

M. Aubert et al. Description raisonnée des sculptures du Moyen Age, de la Renaissance et des temps modernes (Paris, 1950), pp. 51-53.

Guy Isnard. Faux et imitations dans l'Art (Paris, 1959), pp. 143-46.

William N. Mason. “Notes, Records, Comments.” Gardner Museum Calendar of Events 6, no. 21 (20 Jan. 1963), p. 2.

George L. Stout. Treasures from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1969), p. 68. (as by 1135)

Walter Cahn. "Romanesque Sculpture in American Collections. IV. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston." Gesta (1969), pp. 47-49, no. 1a. (as "Two Kings;" French, middle of the 12th century)

Cornelius C. Vermeule III et al. Sculpture in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1977), pp. 75-78, no. 106.

Walter Cahn. "Medieval Sculpture" in James Thomas Herbert Baily (ed.). The Connoisseur: An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors, "Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum" (London, 1978), p. 21.

Rollin van N. Hadley (ed.). The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner 1887-1924 (Boston, 1987), pp. 524-25, 528-39, 614, 618, 620.

Paul Williamson et al. Northern Gothic Sculpture, 1200-1450 (London, 1988), pp. 19-20.

Robert A. Maxwell. Romanesque Parthenay: Art and Urbanism in Fedual Aquitaine. PhD. diss. (New Haven: Yale University, 1999), passim.

Alan Chong and Giovanna De Appolonia. The Art of the Cross: Medieval and Renaissance Piety in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Exh. cat. (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2001), p. 25.

Alan Chong et al. (eds.) Eye of the Beholder: Masterpieces from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 2003), p. 21, ill. (as "Two Elders of the Apocalypse;" mid 12th century)

Meryle Secrest. Duveen: A Life in Art (New York, 2004), pp. 207-223.

Robert A. Maxwell et al. "The Dispersed Sculpture of Parthenay and the Contributions of Nuclear Science." Jounral of the Society for Medieval Archaeology (2005), pp. 247-80, no. 7, fig. 7.

Charles T. Little (ed.). Set in Stone: The Face in Medieval Sculpture. Exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007), pp. 86-87, 189.

Robert A. Maxwell. The Art of Medieval Urbanism: Parthenay in Romanesque Aquitaine (Philadelphia, 2007), pp. 147, 222-23, 229, 237, 244, 249, fig. 222.

Robert A. Maxwell. "Accounting for taste: American collectors and twelfth-century French sculpture." Journal of the History of Collections (Feb. 2015), pp. 1-12, fig. 4. (dated about 1160s-1170s with restoration)

ProvenanceNotesCreated for the upper facade of the church of Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre, Parthenay in the mid 12th century. The facade would have had three registers. These two figures would have likely occupied the middle register, and various biblical scenes in high relief, including an Annunciation to the Shepherds (now housed at the Musée du Louvre, Paris) and the equestrian figure of Christ Entering Jerusalem (museum no. S7n2), occupied the upper register.

Sold by the Ursuline community with the rest of Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre and its convent to Pierre-Jean Andrieux, Nantes, a former priest, in 1796.

Probably relocated to the garden of the former convent by 1834.

Purchased back from Pierre-Jean Andrieux by the Ursuline community with the church and its associated properties in for the purpose of making the church a protected monument in 1856.

Recorded in the convent garden (with museum no. S7n1) in 1876.

Purchased by the antiquarian and art dealer Valentin Guille, Fontenay-le-Co, Paris, with the Christ Entering Jerusalem (museum no. S7n2), and two more sculptures now in the collection of the Musée du Louvre, Paris from Nathalie Guilhard, one of two individuals who had inherited ownership of the church and convent, for 600 francs probably in 1910.

Purchased by the antiquarian and art dealer Victor Poulit, Nantes for 1,200 francs from Valentin Guille immediately following his acquisition.

Purchased by the antiquarian Auguste Duthil, Bordeaux and by the Belgian art dealer Georges-Joseph Demotte (1877-1923), Paris from Poulit a few days later. Soon after this, Demotte purchased Duthil's sculptures, reuniting the lot.

Purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner from Georges-Joseph Demotte (1877-1923), Paris for 150,000 francs on 15 September 1916, through the American art historian Bernard Berenson.

Sold by the Ursuline community with the rest of Notre-Dame-de-la-Couldre and its convent to Pierre-Jean Andrieux, Nantes, a former priest, in 1796.

Probably relocated to the garden of the former convent by 1834.

Purchased back from Pierre-Jean Andrieux by the Ursuline community with the church and its associated properties in for the purpose of making the church a protected monument in 1856.

Recorded in the convent garden (with museum no. S7n1) in 1876.

Purchased by the antiquarian and art dealer Valentin Guille, Fontenay-le-Co, Paris, with the Christ Entering Jerusalem (museum no. S7n2), and two more sculptures now in the collection of the Musée du Louvre, Paris from Nathalie Guilhard, one of two individuals who had inherited ownership of the church and convent, for 600 francs probably in 1910.

Purchased by the antiquarian and art dealer Victor Poulit, Nantes for 1,200 francs from Valentin Guille immediately following his acquisition.

Purchased by the antiquarian Auguste Duthil, Bordeaux and by the Belgian art dealer Georges-Joseph Demotte (1877-1923), Paris from Poulit a few days later. Soon after this, Demotte purchased Duthil's sculptures, reuniting the lot.

Purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner from Georges-Joseph Demotte (1877-1923), Paris for 150,000 francs on 15 September 1916, through the American art historian Bernard Berenson.