Ceramic Plate: A Courtly Couple

maker

Unknown

Dateabout 1208

Place MadeKashan, Isfahan province, Iran, Middle East

MediumFritware with overglaze-painted luster design and splashes of turquoise

Dimensions35 cm (13 3/4 in.)

ClassificationsVessels

Credit LineIsabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Accession numberC15w10

eMuseum ID730156

EmbARK ObjectID11675

TMS Source ID862

Last Updated8/14/24

Status

Not on viewWeb CommentaryThe invention of luster painting – the decoration of ceramics with a glittering, metallic film – is usually credited to ninth-century Muslim potters in Iraq. A complicated technique in which metal oxides are fired in a reducing kiln, luster painting passed within a few centuries from Iraq via Egypt to Iran (Persia), presumably through migrant potters who guarded the technique as a trade secret. The decorative potential of luster’s other-worldly iridescence was explored by Iranian potters during the twelfth through fourteenth centuries, a period of brilliant innovation and prolific production in the ceramic arts circumscribed by the reigns of the Great Saljuqs and the Il-Khanids.

The finest painting and most ambitious decorative programs for lusterware were produced in the central Iranian city of Kashan. Several stylistic features of the Gardner Museum’s plate suggest an attribution to Kashan: the monumental figures set against a luster background, the kidney-shaped leaves, the plump-breasted bird, and the minute spirals painted and scratched through the luster. Scholars have linked the plate to two famous luster-painted plates in the Freer Gallery of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum, because their ceramic bodies seem to have been produced from the same mold with 29 scallops in the cavetto. The Freer plate, arguably the most accomplished of the three, bears a date of 1210.

At its center, the plate in the Gardner Museum presents a vignette of courtly life in the classical period of Islamic civilization. The elevated status of an elegantly attired couple is revealed in their refined decorum and possessions. The serene countenances of the couple betray neither the pains of separation and romantic disappointment lamented in the concentric bands of poetry, nor the pleasures of their musical activity. The figure on the left plucks an ancient harp (chang) that rests on his knee. For centuries, the Persian harp was one of the most prized instruments in aristocratic circles, and was celebrated in poetry and painting. The lower hand of the figure on the right holds a folded handkerchief (mandil), another allusion to wealth and refined manners. Beautiful and costly handkerchiefs were a source of pride among the wealthier classes and an elaborate etiquette governed their usage.

Source: Mary McWilliams, "Ceramic Plate: A Courtly Couple," in Eye of the Beholder, edited by Alan Chong et al. (Boston: ISGM and Beacon Press, 2003): 168.

The finest painting and most ambitious decorative programs for lusterware were produced in the central Iranian city of Kashan. Several stylistic features of the Gardner Museum’s plate suggest an attribution to Kashan: the monumental figures set against a luster background, the kidney-shaped leaves, the plump-breasted bird, and the minute spirals painted and scratched through the luster. Scholars have linked the plate to two famous luster-painted plates in the Freer Gallery of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum, because their ceramic bodies seem to have been produced from the same mold with 29 scallops in the cavetto. The Freer plate, arguably the most accomplished of the three, bears a date of 1210.

At its center, the plate in the Gardner Museum presents a vignette of courtly life in the classical period of Islamic civilization. The elevated status of an elegantly attired couple is revealed in their refined decorum and possessions. The serene countenances of the couple betray neither the pains of separation and romantic disappointment lamented in the concentric bands of poetry, nor the pleasures of their musical activity. The figure on the left plucks an ancient harp (chang) that rests on his knee. For centuries, the Persian harp was one of the most prized instruments in aristocratic circles, and was celebrated in poetry and painting. The lower hand of the figure on the right holds a folded handkerchief (mandil), another allusion to wealth and refined manners. Beautiful and costly handkerchiefs were a source of pride among the wealthier classes and an elaborate etiquette governed their usage.

Source: Mary McWilliams, "Ceramic Plate: A Courtly Couple," in Eye of the Beholder, edited by Alan Chong et al. (Boston: ISGM and Beacon Press, 2003): 168.

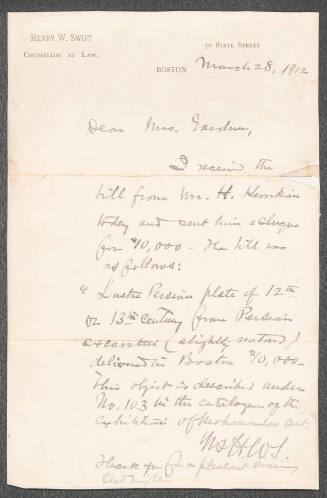

BibliographyNotesH. Kevorkian. Catalogue of the Exhibition of Mohammedan Art from the Caliphate Epoch to the XVIII Century. Exh. cat. (New York: Folsom Galleries, 1912), p. 34, no. 103. (as discovered at Hamadan, 12th century)

Gilbert Wendel Longstreet and Morris Carter. General Catalogue (Boston, 1935), p. 102. (as Persian (Rayy), 13th or 14th century)

Rollin Hadley. “Notes, Records, Comments.” Gardner Museum Calendar of Events 9, no. 25 (20 Feb. 1966), p. 2. (as Persian, Rayy or Kashan, 13th century)

George L. Stout. Treasures from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1969), pp. 90-91, ill. (as Persian, 13th century; possibly Kashan, about 1210)

Walter B. Denny. "Some Islamic Objects in the Gardner Museum." Fenway Court (1971), pp. 11-12, fig. 8. (as Kashan, early 13th century)

Yasuko Horioka et al. Oriental and Islamic Art: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1975), pp. 114-15, no. 50. (as Persian (Kashan), about 1210)

Walter B. Denny. "Far Eastern and Islamic Art" in James Thomas Herbert Baily (ed.). The Connoisseur: An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors, "Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum" (London, 1978), pp. 78, 80, fig. C. (as Persian (Kashan), about 1210)

Rollin van N. Hadley. Museums Discovered: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1981), pp. 202-03, ill. (as Persian (Kashan), about 1210)

Rollin van N. Hadley (ed.). The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner 1887-1924 (Boston, 1987), p. 496.

Mary McWilliams in Alan Chong et al. (eds.) Eye of the Beholder: Masterpieces from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 2003), pp. 168-69, ill. (as Iranian (Kashan), about 1200)

Gilbert Wendel Longstreet and Morris Carter. General Catalogue (Boston, 1935), p. 102. (as Persian (Rayy), 13th or 14th century)

Rollin Hadley. “Notes, Records, Comments.” Gardner Museum Calendar of Events 9, no. 25 (20 Feb. 1966), p. 2. (as Persian, Rayy or Kashan, 13th century)

George L. Stout. Treasures from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1969), pp. 90-91, ill. (as Persian, 13th century; possibly Kashan, about 1210)

Walter B. Denny. "Some Islamic Objects in the Gardner Museum." Fenway Court (1971), pp. 11-12, fig. 8. (as Kashan, early 13th century)

Yasuko Horioka et al. Oriental and Islamic Art: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1975), pp. 114-15, no. 50. (as Persian (Kashan), about 1210)

Walter B. Denny. "Far Eastern and Islamic Art" in James Thomas Herbert Baily (ed.). The Connoisseur: An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors, "Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum" (London, 1978), pp. 78, 80, fig. C. (as Persian (Kashan), about 1210)

Rollin van N. Hadley. Museums Discovered: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 1981), pp. 202-03, ill. (as Persian (Kashan), about 1210)

Rollin van N. Hadley (ed.). The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner 1887-1924 (Boston, 1987), p. 496.

Mary McWilliams in Alan Chong et al. (eds.) Eye of the Beholder: Masterpieces from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, 2003), pp. 168-69, ill. (as Iranian (Kashan), about 1200)

MarksNotesInscribed (around the outer rim, in naskhi script): The heart is branded with the grief of your love on its soul; separation from you makes the world like a prison; that heart that has not the patience for union with you, alas that it can suffer through separation.

Inscribed (on the reverse side, in blue chalk): 721

Inscribed (on the reverse side, in blue chalk): 721

ProvenanceNotesDiscovered at Hamadan, Iran inside a strong brick pot, under the supervision of the Armenian archaeologist and collector Hagop Kevorkian (1872-1962) before 1912.

Purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner from Hagop Kevorkian, New York for $10,000 on 28 March 1912.

Purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner from Hagop Kevorkian, New York for $10,000 on 28 March 1912.