John Singer Sargent

Florence, 1856 - 1925, London

LC Heading: Sargent, John Singer, 1856-1925

10/6/2017 I.S.

Sargent, John Singer (12 Jan. 1856-15 Apr. 1925), painter, was born in Florence, Italy, the son of FitzWilliam Sargent, a surgeon, and Mary Newbold Singer. Though born in Italy and raised abroad, Sargent considered himself American. Sargent's parents were from Pennsylvania, and his paternal line included Epes Sargent of Gloucester, Massachusetts, whose portrait was painted by John Singleton Copley. Sargent's early education consisted of a patchwork of tutors and short periods of attendance at local schools in Austria, Italy, England, and France. Recognizing her young son's skill, Sargent's mother, who herself painted in watercolor, taught him to use this demanding medium. A childhood friend, Violet Paget (pseudonym Vernon Lee), suggested in her 1927 essay, "J.S.S.: In Memoriam," that Sargent's painting gift came from his mother, who, she wrote, was invariably "painting, painting, painting away, always an open paint-box in front of her, through all the forty years I knew her" (Charteris, p. 235). Sargent's cousins Emma Worcester Sargent and Charles Sprague Sargent noted in their 1923 history of the Sargent family that Mary Sargent instructed her son that he "might begin as many sketches each day as he liked, but that one of them must be finished" (p. 86). His mother's instruction served as the basis for Sargent's lifetime of disciplined, artistic production.

Sargent received more formal artistic education at the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Florence. By the age of eighteen Sargent and his family were firmly committed to his pursuit of a career as an artist. In Paris he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he remained for three years, finishing his studies there in 1877. He made his first trip to the United States in 1876 in order to claim his American citizenship. With his mother and sister he visited the Centennial Exposition, traveled widely in the United States, and then returned to Paris to resume his professional studies. In 1874, concurrent with his academic training and probably more important to his future career, Sargent entered the teaching studio of Émile Auguste Carolus-Duran, a portrait painter and muralist of French and Spanish descent. There he met American artist James Carroll Beckwith, with whom he shared a studio in Paris. In 1877 the two young artists assisted Carolus-Duran with his ceiling decorations for the Palais du Luxembourg. With this experience of large-scale decorative work, Sargent established the foundation for his own later important mural commissions in Boston. In addition, Sargent's association with Carolus-Duran enabled him to gain access to Parisian patrons and to begin to build his reputation as a painter of portraits. Between 1877 and 1879 Sargent exhibited several works at the Salon, and in 1879 his portrait of Carolus-Duran (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass.) received an honorable mention.

Sargent confirmed his talent with several subject pictures, including Fumée d'Ambre Gris (1880, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) and El Jaleo (1882, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston), both of which were exhibited at the Salon and received considerable critical praise. One critic wrote in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts of El Jaleo, a large-scale oil painting of a Spanish dancer and musicians in a dusky interior, that it "reveals the most remarkable qualities of observation and invention" (Downes, p. 129). El Jaleo builds on Sargent's study of seventeenth-century Spanish painter Diego Velasquez, whose works he had copied at the Prado Museum in Madrid in 1879 at the suggestion of Carolus-Duran. Sargent followed the success of his dramatic El Jaleo with a portrait of Virginie Gautreau (Madame Pierre Gautreau) begun in 1883 and completed and exhibited at the Salon in 1884 (Metropolitan Museum of Art). The portrait, exhibited under the title Madame X, did not receive the kind of positive attention El Jaleo had. In fact, it caused a scandal: both Sargent's skill and his subject's renowned beauty were criticized as being superficial. In 1915, after three decades of hanging prominently in the artist's studio, the controversial portrait was chosen by Sargent as his entry in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Shortly after that exhibition he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, noting that he considered the painting one of his finest works.

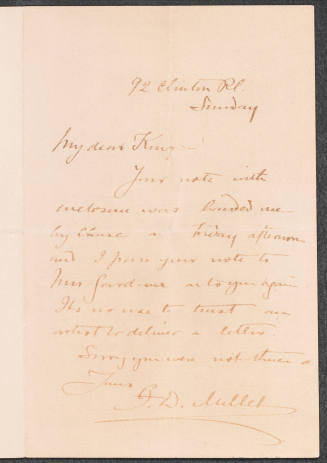

Sargent's experience in Paris was discouraging and might have proven disastrous for his career had he not had good friends in London, including American author Henry James, whom Sargent met in 1884 and who helped Sargent establish himself in England. In 1886 Sargent left Paris for London and the United States. James's review of Sargent's work was published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine in October 1887. The essay included biographical data as well as descriptions of and responses to Sargent's major works to date, including El Jaleo, his innovative Venetian subject pictures, as well as his portraits of Carolus-Duran, Virginie Gautreau, the Boit children (1882, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Charlotte Louise Burckhardt (1882, Metropolitan Museum of Art), which received James's highest praise. James concluded, "Mr. Sargent is so young, in spite of the place allotted to him in these pages, so often a record of long careers and uncontested triumphs, that, in spite also of the admirable works he has already produced, his future is the most valuable thing he has to show" (p. 691). James's critical yet complimentary essay, published in a popular American periodical, enhanced Sargent's reputation in the United States. Upon the occasion of James's seventieth birthday Sargent was commissioned to paint the author's portrait, which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Sargent and James remained friends until James's death in 1916.

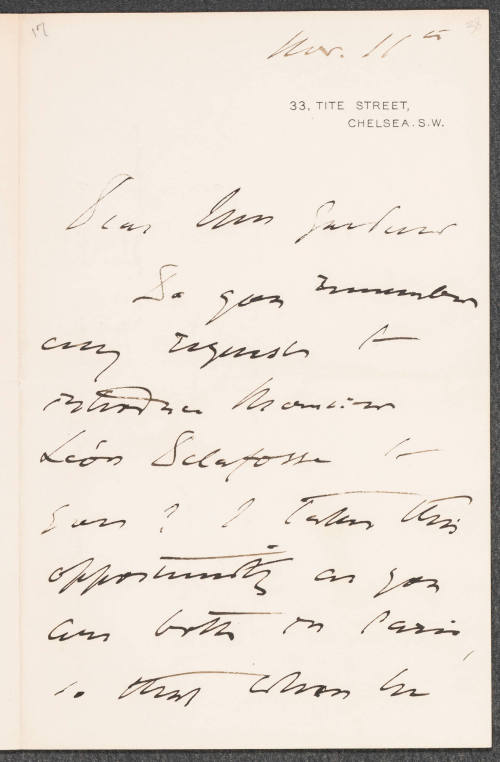

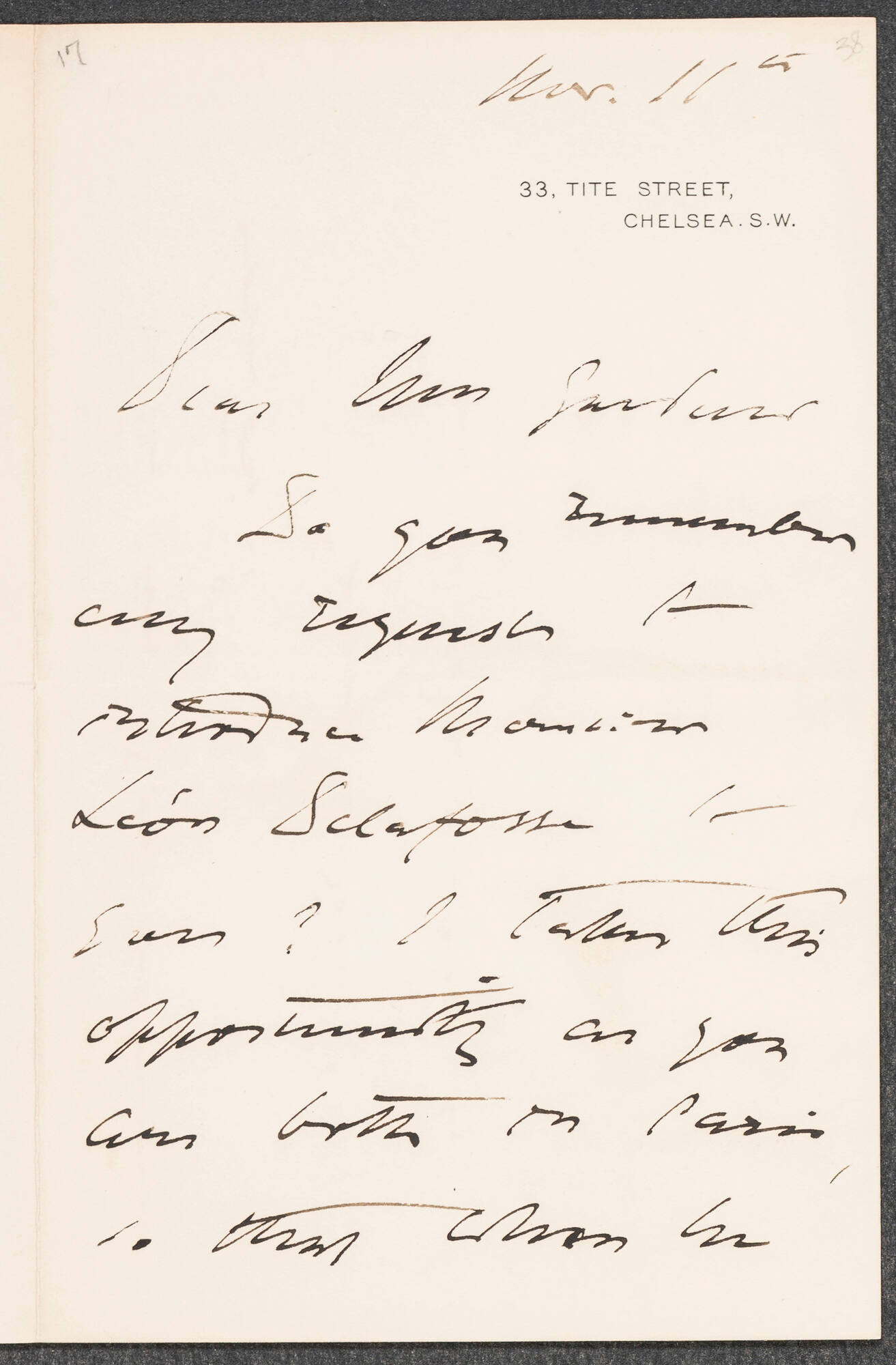

In 1886 Sargent rented James McNeill Whistler's former studio on Tite Street in London. Sargent met Whistler in 1881, and although the two artists were never particularly close socially or artistically, Sargent respected Whistler's work and in 1892 recommended Whistler as a contributor to the murals proposed for the Boston Public Library. Sargent is consistently linked to his American contemporaries Whistler and Mary Cassatt because, like them, he spent much of his professional career in Europe, the implication being that he, like them, withdrew from mid- and late nineteenth-century America in favor of Europe. However, Sargent was born and educated abroad and therefore could not withdraw to Europe; rather he remained where he had been raised and traveled regularly to the United States to carry out commissions and to visit family and friends.

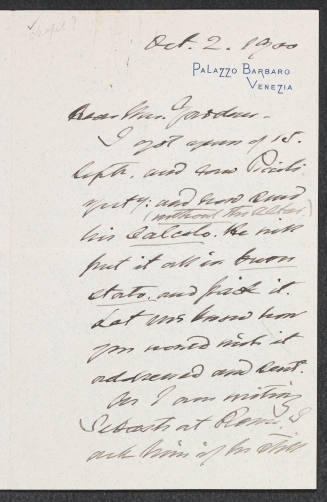

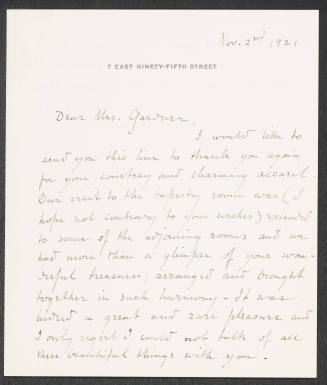

After moving to London Sargent began to receive many important portrait commissions from American and English patrons. During his 1887-1888 trip to the United States he painted Elizabeth Allen Marquand (1887, Art Museum, Princeton University), Mrs. Edward D. Boit (1888, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Mrs. Adrien Iselin (1888, National Gallery of Art). Sargent's portraits were greeted with praise, but the praise was not unqualified. One observer wrote with mock horror or delight in the Art Amateur (Apr. 1888) that "Boston propriety has not yet got over the start Mr. John D. [sic] Sargent's exhibition of portraits at the St. Botolph Club gave it. . . . Not, of course that there were any nudities . . . but the spirit and style of the painter were so audacious, reckless and unconventional! He actually presented people in attitudes and costumes that were never seen in serious, costly portraits before." The author's comments suggest that Sargent's style was not entirely familiar to or embraced by his audience. His style was unconventional, and it both puzzled and pleased audiences because of the "attitudes" in which he presented his sitters. A particularly compelling work of this trip was his portrait of wealthy Boston art collector and trendsetter Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). Henry James had introduced Gardner to Sargent when she visited London in 1886. Their meeting resulted in a commission that Sargent carried out at Gardner's home in Boston. The full-length portrait, in which Gardner directly engages her viewers from a position of authority, was a test of the artist's patience, as it went through eight renderings before Gardner accepted the ninth and final version. Gardner remained an important patron, purchasing El Jaleo for the Spanish court of her mansion on Fenway Park in Boston, as well as ten watercolors and six smaller oils.

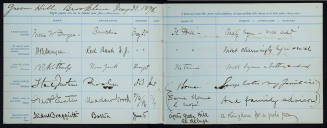

While active as a portrait painter, Sargent's subjects also included landscape and genre. One of Sargent's most important works from the 1880s was a subject picture titled Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885-1886, Tate Gallery, London). The image, a depiction of two children lighting Chinese lanterns at dusk in a garden, was painted over a two-year period in the garden at "Farnham House" at Broadway, an artists' colony in the English Cotswolds. It is a large-scale work and was painted entirely outdoors. One of Sargent's early biographers, William Howe Downes, quotes a letter from Edwin Austin Abbey to Charles Parsons in which Abbey describes the painting as being "seven feet by five" and writes that "as the effect only lasts about twenty minutes a day--just after sunset--the picture does not get on very fast" (Downes, p. 24). Sargent exhibited Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose at the Royal Academy in 1887. It was acquired for the Tate Gallery that year and, according to Downes, was the first of Sargent's paintings to be purchased by a public institution. Painting outdoors, or en plein air, was a popular practice among the French impressionists, particularly Claude Monet. Sargent met Monet in 1876 and painted with him in 1887, an event recorded in Sargent's image titled Claude Monet Painting at the Edge of a Wood (Tate Gallery). Sargent is credited by one biographer, Charles Merrill Mount, with bringing impressionism to England. Over several seasons spent at Broadway, Sargent painted a number of masterful plein air works, including St. Martin's Summer (1888, private collection), Violet Fishing (1889, Ormond family), and Paul Helleu Sketching with His Wife (1889, Brooklyn Museum). Paintings such as these from the mid- and late 1880s led observers to place Sargent among the American impressionists. The classification may indeed be appropriate for these works but does not characterize Sargent's oeuvre.

In 1890 Sargent and Abbey were asked to contribute murals to the new Boston Public Library designed by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White. Both artists accepted the commission. Sargent's work was to be installed on the vaulted ceiling of the hall outside the special collections library. His subject was to have been Spanish literature, but after returning from a trip to the Near East in the winter of 1890-1891 he changed his subject to religious history. He did not conceive of the mural cycle as a chronological history of world religions but rather as a complex composition examining aspects of religious thought. Sargent returned to his London studio to sketch out ideas for his figures and paint the final canvases. The paintings were then shipped to the United States and installed by craftsmen who finished the architectural details and gilding with the canvases in place. Sargent's first section was installed in 1895, followed by three more in 1903, 1916, and 1919. The murals were well-received by contemporary critics, with the exception of his 1919 panel, "Synagogue," which the Boston Jewish community criticized for what it perceived as a negative interpretation of Judaism.

While at work on the project for the Boston Public Library, Sargent continued to receive numerous portrait commissions, including one from President Theodore Roosevelt completed in 1903 (While House Collection), as well as two additional mural commissions, from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (1916-1921) and from the Widener Memorial Library at Harvard University (1922). During World War I the British government commissioned Sargent to produce a work in honor of the joint effort of the British and Americans. Sargent traveled in 1918 to the western front, where he painted a number of watercolors of the soldiers and the landscape (Imperial War Museum, London). Based on his experience at the western front, he painted his almost life-sized work Gassed to fulfill his commission (1919, Imperial War Museum). Also at this time he painted a large-scale portrait of British officers for the National Portrait Gallery.

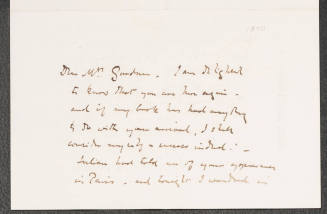

In addition to placing himself in the public eye, Sargent's American murals gave him the opportunity he needed to break away from the restrictive and demanding routine of commissioned portraiture. Flattering the sitter had become drudgery, and in 1907 he wrote Mrs. Daniel Sargent Curtis (a relative) that he "made a vow not to do any more portraits" and "shall soon be a free man." Exceptions to his vow included portraits of President Woodrow Wilson (1917, National Gallery of Ireland) and John D. Rockefeller (1917, Kykurt, Tarrytown, N.Y.).

Having a secure income from the murals enabled Sargent to concentrate on other subjects and media, most notably watercolor. Watercolor played a central role in the last twenty years of Sargent's life. His subjects, taken from his travels across Europe, the Near East, and North America, were familiar to his American and British audiences from their own travels or literary and historical sources; the audience and the artist shared knowledge of the places painted. It has been suggested that Sargent painted in watercolor only on holidays as an escape from portraits and murals; however, Sargent exhibited and sold his watercolors regularly and paid careful attention to the details of their subject, execution, and public display. The first major exhibition of Sargent's watercolors was held at Knoedler's Gallery in New York in 1909. It consisted of approximately eighty-six watercolors of subjects ranging from Venice to Bedouins. Sargent preferred that they be sold as a group to a public institution rather than as individual images to private collectors, and the Brooklyn Museum complied, purchasing eighty-three of the watercolors for its collection. Following Brooklyn's example, in 1912 the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston purchased forty-five watercolors, including images of Carrara and the Simplon Pass; in 1915 the Metropolitan Museum purchased ten, including Italian and Spanish subjects, and in 1950 was given approximately 200 more by the artist's younger sister Violet (Mrs. Francis Ormond); and in 1917 the Worcester Museum purchased eleven, including images of Florida. With such consistent public patronage Sargent could support himself with work of his own choosing.

Sargent never married and after his death in London was survived by his younger sisters, Emily and Violet. His two sisters inherited their brother's work and arranged for it to be dispersed among American institutions.

As Henry James noted in his 1887 essay, John Singer Sargent achieved high standing at a young age. He continued to prove himself throughout his career by exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy and the National Academy of Design in New York (becoming a full member of each in 1897), in the American sections of international expositions, at the Union League in New York and at London's Grosvenor Gallery and Carfax Gallery. In 1907 he was recommended for a knighthood by Britain's King Edward VII but declined as he was unwilling to give up his U.S. citizenship. He was awarded in 1909 both the Order of Merit from France and the Order of Leopold from Belgium. At the height of his career Sargent was immensely popular both professionally and socially. He was not, however, without critics, beginning with the exhibition of Madame X and continuing into the twentieth century. Art critic Roger Fry, for example, was a vocal critic of what he perceived to be Sargent's conservatism in an era of great artistic and cultural change. Indeed, the advent of modernism eventually led to a decline in Sargent's standing. After his death his murals and portraits began to lose their public appeal. The murals were dismissed as vacant, and he was criticized as lacking the talent for such decorative work; his portraits were described as both technically and intellectually superficial. Yet Sargent was still recognized as an important American artist. He brought American art to an international audience and helped strengthen the American patronage of native artists. Sargent's life and work have again become the subject of active scholarship as demonstrated by the abundance of publications and exhibitions that investigate his artistic production.

Bibliography

Sargent's papers consist primarily of correspondence located in the Archives of American Art and in the files of his correspondents, such as the Curtis family in the Boston Athenaeum and Vernon Lee in the Special Collections Library of Colby College, Waterville, Maine. Sargent has been the subject of a number of biographies, including William Howe Downes, John S. Sargent: His Life and Work (1925); Evan Charteris, John Sargent (1927); Charles Merrill Mount, John Singer Sargent: A Biography (1955); and Stanley Olson, John Singer Sargent: His Portrait (1986). In addition to Henry James's article, "John S. Sargent," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Oct. 1887, many contemporary reviews and accounts of Sargent and his work may be found in Robert H. Getscher and Paul G. Marks, James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent: Two Annotated Bibliographies (1986). Monographs on Sargent's art include Richard Ormond, John Singer Sargent: Paintings, Drawings, Watercolors (1970); Carter Ratcliff, John Singer Sargent (1982); and Trevor Fairbrother, John Singer Sargent (1994). Sargent's art has generated important scholarship by individuals such as Margaretta M. Lovell, A Visitable Past: Views of Venice by American Artists, 1860-1915 (1989), and in exhibition catalogs such as Patricia Hills, ed., John Singer Sargent (1986); Mary Crawford Volk, ed., John Singer Sargent's El Jaleo (1992); Theodore Stebbins Jr., ed., The Lure of Italy: American Artists and the Italian Experience, 1760-1914 (1992); and Marc Simpson, ed., Uncanny Spectacle: The Public Career of the Young John Singer Sargent (1997). Museums holding significant collections of Sargent's watercolors have compiled rich catalogs of their holdings, including Susan Strickler, ed., American Traditions in Watercolor: The Worcester Art Museum Collection (1987); Metropolitan Museum of Art, American Watercolors from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with commentaries by Stephen Rubin (1991); and Sue Welsh Reed and Carol Troyen, Awash in Color: Homer, Sargent and the Great American Watercolor (1993). Among the doctoral dissertations that focus on different aspects of Sargent's work are M. Elizabeth Boone, "Vistas de Espana: American Views of Art and Life in Spain, 1860-1898" (City Univ. of New York Graduate Center, 1995); Kathleen L. Butler, "Tradition and Discovery: The Watercolors of John Singer Sargent" (Univ. of California, Berkeley, 1994); and Derrick Cartwright, "Reading Rooms: Interpreting the American Public Library Mural, 1890-1930" (Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1994).

Kathleen L. Butler

Back to the top

Citation:

Kathleen L. Butler. "Sargent, John Singer";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00778.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 10:58:09 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated9/26/24

Troy, New York, 1861 - 1933, Boston

Boston, 1825 - 1908, Venice

Garden City, New York, 1861 - 1890, Boston

Dublin, 1848 - 1907, Cornish, New Hampshire

Brookline, Massachusetts, 1841 - 1927, Boston

Boston, 1871 - 1961, Boston

Boston, 1846 - 1894, Dinard, France

Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, 1846 - 1912