Francis Hopkinson Smith

Smith, Francis Hopkinson (23 Oct. 1838-7 Apr. 1915), mechanical engineer, writer, and artist, was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of Francis Smith, a musician, mathematician, and philosopher, and Susan Teakle. Smith was reared in the genteel society of old Baltimore, where he studied for entrance to Princeton University. Smith's family suffered economic ruin, however, and he never attended college. Before the Civil War he held jobs in a hardware store and an ironworks. Around 1858 he moved to New York City, where, after some training with a partner named James Symington, he set up an engineering firm. Over the years he increasingly complemented this enterprise with his work in the fine arts and as a speaker. He was usually thought of, and perhaps thought of himself, as a southern gentleman. In 1866 Smith married Josephine Van Deventer of Astoria, New York. They had two children.

Among Smith's major feats as an engineer were the government seawall around Governor's Island; another at Tompkinsville, Staten Island; the Block Island Breakwater; and the foundation of Bedloe's Island for Bartholdi's Statue of Liberty (1885-1886). His own favorite work was Race Rock Lighthouse (1871-1879), eight miles at sea off New London, Connecticut.

Smith also studied painting with the artist Alfred Jacob Miller. He became a member of the prestigious Tile Club in New York. Other members included painters such as Edwin Austin Abbey, Elihu Vedder, and William Merritt Chase. Smith traveled frequently to various parts of the world, sketching, painting, and taking notes (see, e.g., Well-Worn Roads of Spain, Holland, and Italy [1886] and A White Umbrella in Mexico [1889]). He referred to "my romantic life," getting to know people by going into the streets and sketching scenes while sitting under his artist's umbrella. Smith wrote and illustrated many books describing the places he had traveled, including Gondola Days (1897), Venice of To-Day (1897), Charcoals of New and Old New York (1912), In Thackeray's London (1913), and In Dickens' London (1914).

"Night in Venice," in Gondola Days, exemplifies Smith's technique of creating atmosphere and his almost musical facility with language: "A night of ghostly gondolas, chasing specks of stars in dim canals; of soft melodies broken by softer laughter; of tinkling mandolins, white shoulders, and tell-tale cigarettes. . . . No pen can give this beauty, no brush its color, no tongue its delight." With "pen," "brush," and "tongue," he refers to his own varied talents.

Smith's artist's eye for detail of color, texture, and proportion led to his creating brilliant imagery in fiction also. His travel sketches complemented his fiction style, and his close observations of people helped him produce fine fictional characterizations. Examples are in his books of short stories: A Day at Laguerre's and Other Days (1892), The Other Fellow (1899), At Close Range (1905), and The Wood Fire in No. 3 (1905). His stories stress atmosphere. It is for his novels, however, that Smith has been taken most seriously, as a bestseller in his lifetime and as a premodern writer whose works mark the end of the genteel era in the fine arts in America.

A contemporary, John S. Patton, described Smith as "of medium height, active, with iron-gray hair, close cropped, and gray moustaches, looking, at the first glance, like a prosperous French man of affairs." Smith's friend and fellow novelist Thomas Nelson Page spoke of him as possessing a bundle of qualities--always young, independent yet readily friendly, distinguished, witty, cheerful, optimistic, modest in his popularity, painstaking as a writer. He was often an advocate of liberal causes. For example, he forbade the exhibition of his pictures in Paris because of the Dreyfus case.

There is a pronounced autobiographical element in much of Smith's fiction. And dramatist Augustus Thomas noticed that "women in his treatment were always objects of romance to be protected." Literary historian Arthur Hobson Quinn remarks on Smith's constant revisions and of how, before writing The Tides of Barnegat (1906), he "went to Barnegat Light . . . and lived among the life-saving crew to gain the atmosphere." In the preface to the posthumously published novel Enoch Crane (1916), his son noted that Smith thought of his fictional characters as real persons: "It was my father's practise, in planning a novel, first to prepare a most complete synopsis from beginning to end--never proceeding with the actual writing of the book until he had laid out the characters and action of the story--chapter by chapter."

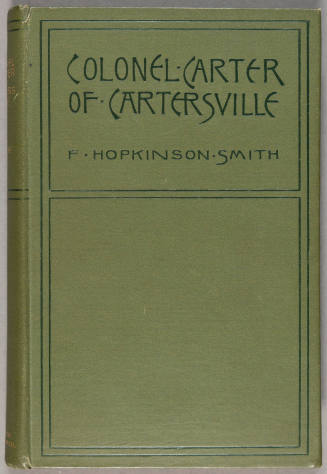

Probably the best liked of Smith's novels was his first, Colonel Carter of Cartersville (1891), about a conservative Virginia gentleman, stranded in New York, who tells after-dinner stories. Featured are pictures of happy Old South blacks and benevolent masters. The book was illustrated by Edward W. Kemble and the author. One of the stories, "One-Legged Goose," illustrates Smith's humor and his use of dialect in telling a tale: "Dem was high times. . . . Git up in de mawnin' an' look out ober de lawn, an' yer come fo'teen or fifteen couples ob de fustest quality folks, all on horseback ridin' in de gate. . . . Old marsa an' missis out on de po'ch, an' de little pickaninnies runnin' from de quarters. . . . " In a footnote Smith wrote, "This story . . . I have told for so many years and to so many people, and with such varied amplifications, that I have long since persuaded myself that [it is] my own. . . . [But] I know [it] is as old as the 'Decameron.' " A sentimental sequel, Colonel Carter's Christmas, appeared in 1903.

Smith's next triumph was Tom Grogan (1896), a novel about blackmail, arson, and attempted murder--as well as labor strife--on the New York waterfront. The wife of a stevedore who dies becomes the "Tom" running the deceased husband's business in secret. She is an extremely strong character, strong of both body and spirit. Like Tom Grogan, Caleb West, Master Diver (1898) in part exploits Smith's engineering expertise. First serialized in the Atlantic Monthly in 1897-1898, Caleb West was also issued, in 1899, in a "special edition limited to one hundred thousand copies." In 1902 The Fortunes of Oliver Horn continued Smith's high reputation and large sales. It is a more noticeably autobiographical novel, which Quinn calls a "romantic-idealistic" story. Then, in 1906, Smith published perhaps his best-written novel, The Tides of Barnegat. Here he deals with family problems, including divorce. Although tragedy strikes Barnegat, a New Jersey fishing community, the selfless heroine and the book's secondary characters come to a happy ending.

The chapter "The Surprise," from Peter (1908), one of Smith's late novels, illustrates his style in description and dialogue. There he writes:

It was wonderful how young he looked, and how happy he was, and how spry his step, as the two turned into William Street and so on to the cheap little French restaurant with its sanded floor, little tables for two and four, with their tiny pots of mustard and flagons of oil and red vinegar--this last, the "left-overs" of countless bottles of Bordeaux--to say nothing of the great piles of French bread weighing down a shelf beside the proprietor's desk, racked up like cordwood, and all the same color, length and thickness. . . . "And now, I have got a surprise for you, Uncle Peter," cried Jack, smothering his eagerness as best he could. The old fellow held up his hand, reached for the shabby, dust-begrimed bottle, that had been sound asleep under the sidewalk for years; filled Jack's glass, then his own; settled himself in his chair and said with a dry smile: "If it's something startling, Jack, wait until we drink this," and he lifted the slender rim to his lips. "If it's something delightful, you can spring it now."

Smith's is a most readable, word-painting kind of fiction.

Scribner's published a ten-volume Beacon Edition of Smith's works around 1903, revised and augmented, with illustrations and high-quality paper and bindings. The illustrators included Howard Chandler Christy, whose works perfectly complement Smith's. This edition was increased to twelve volumes around 1906.

Between 1902 and 1915 Scribner's also issued, in high compliment to the author, a twenty-three volume edition, The Novels, Stories and Sketches of F. Hopkinson Smith. Many illustrations--by various hands--are in color, and here a reader can see Smith's own impressionistic drawings wonderfully reproduced.

Smith received many honors for his work in the fine arts: a bronze medal at the Buffalo Exposition in 1901, a silver medal from the Charleston Exposition in 1902, and gold medals from the Philadelphia Art Club in 1902 and from the American Art Society in 1902. In Augustus Thomas's published tribute to Smith, he called him "an artist . . . of living," who remains "notable for his expression . . . as measured by his own emotions." His was the "ability to transmute the ordinary into the beautiful." Smith died in New York.

Smith left a heritage of engineering feats that provide safer and greater access to the waters around New York City, along with his fine starlike design for the base of the Statue of Liberty. He exemplifies in his travel sketches and in his paintings and illustrations the rare renaissance mind and person of letters of his era. His fiction is still rewarding reading, and his career shows how a writer of enormous fame can fade into obscurity as times and tastes change.

Bibliography

The main repositories of Smith's manuscripts are the Beinecke Library, Yale University, and the Alderman Library, University of Virginia. Major published works not mentioned above are Old Lines in New Black and White (1855), A Book of the Tile Club (1890), American Illustrators (1892), A Gentleman Vagabond, and Some Others (1895), The Under Dog (1903), The Veiled Lady (1907), The Romance of an Old-Fashioned Gentleman (1907), Forty Minutes Late (1909), and The Arm Chair at the Inn (1912). There is no major biography. For critical assessment of Smith and his work, see Horace Spencer Fiske, Provincial Types in American Fiction; Theodore Hornberger (1903); "The Effect of Painting on the Fiction of F. Hopkinson Smith," University of Texas Studies in English 23 (1943): 162-92, and "Painters and Painting in the Writings of F. Hopkinson Smith," American Literature 16 (1944): 1-10; H. W. Mabie, "Hopkinson Smith and His Work," Book Buyer 25 (1902): 17-20; Thomas Nelson Page, "Francis Hopkinson Smith," Scribner's, Sept. 1915, pp. 305-13; Arthur Hobson Quinn, American Fiction: An Historical and Critical Survey (1936); Courtland Y. White III, "Francis Hopkinson Smith" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1932); and G. Willets, "F. Hopkinson Smith in Three Professions," Arena 22 (1899): 68-70. See also Augustus Thomas, Commemorative Tribute to Francis Hopkinson Smith (1922). Obituaries are in American Art News, 13 Apr. 1915, and the New York Times, 8 Apr. 1915.

William K. Bottorff

Online Resources

Francis Hopkinson Smith, Colonel Carter of Cartersville, 1919

http://metalab.unc.edu/docsouth/smith/menu.html

From the Documenting the American South Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Back to the top

Citation:

William K. Bottorff. "Smith, Francis Hopkinson";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01524.html;

American National Biography Online October 2008 Update.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:07:15 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2008 American Council of Learned Societies.