Sarah Wyman Whitman

Lowell, 1842 - 1904, Boston

Whitman, Sarah de St. Prix Wyman (5 Dec. 1842-25 June 1904), designer and fabricator of stained glass, bookcover designer, painter, and writer, was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, the daughter of William W. Wyman, a banker, and Sarah Amanda Treat of Boston. Immediately following her birth, in the wake of a financial scandal and legal trials involving her father, the family moved to Baltimore. The Wymans returned to Lowell in 1853, but throughout her life, Baltimore held a special place in Whitman's heart, and she returned regularly to her childhood home for family visits and Christmas holidays.

In Lowell, young Sarah was fortunate to have as her tutor the intellectually gifted Elizabeth "Lissy" Mason Edson, daughter of the rector of St. Ann's Episcopal Church. Edson introduced Sarah to the plays of William Shakespeare, the work of English historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, poetry, penmanship, and drawing. She taught her German and French and instilled in her an enduring love and appreciation for learning. The two women became and remained cherished friends.

In June 1866 Sarah Wyman married Henry Whitman of Boston, a Nova Scotia-born wool merchant. It was an unhappy, childless marriage, but it gave her the freedom to pursue a career in art. Once settled in Boston, Whitman entered the studio of William Morris Hunt, champion of the Barbizon school, teacher, and cultural arbiter; she studied with Hunt for three winter seasons (1868-1871). In 1870-1871 she also attended sculptor William Rimmer's classes in drawing and artistic anatomy. Four years later, in the summer of 1875, Whitman resumed her studies. Armed with letters of introduction from Hunt, she toured Italy and France, probably with Elizabeth Bartol, another former member of Hunt's class. Whitman twice returned to France, in the summer of 1877 and again late in 1878 or early 1879, to study with Hunt's former master Thomas Couture. Whitman's studies with Couture marked the end of her formal training. She revisited Europe many times but did not seek out other teachers. The influence of Hunt and Couture remained constant and strongest in her portraits, in the soft modeling of the figure, the shadowy harmonies of contrasting lights and darks, the broken brush work. The summer of 1877 was the defining moment for Whitman: it led to her decision to live "the life of an artist in the thick of conventional adjustments & demands," that is, regardless of the disapproval then ascribed to women who earned money from their art.

Despite her doubts, given her limited formal education and art training, Whitman's accomplishments were remarkable. A member of both the National Academy of Design (1877) and the Society of American Artists (1880), she began to exhibit almost yearly in New York and Boston. William Brownell, writing in Scribner's 1881, considered her to be "representative of the successful women-painters of Boston." Whitman's reputation as a celebrated painter of flowers, landscapes, and portraits led to her first one-woman exhibition of oil paintings in 1882 at Doll & Richards, one of Boston's most prestigious galleries, and possibly to a second exhibition there in 1883.

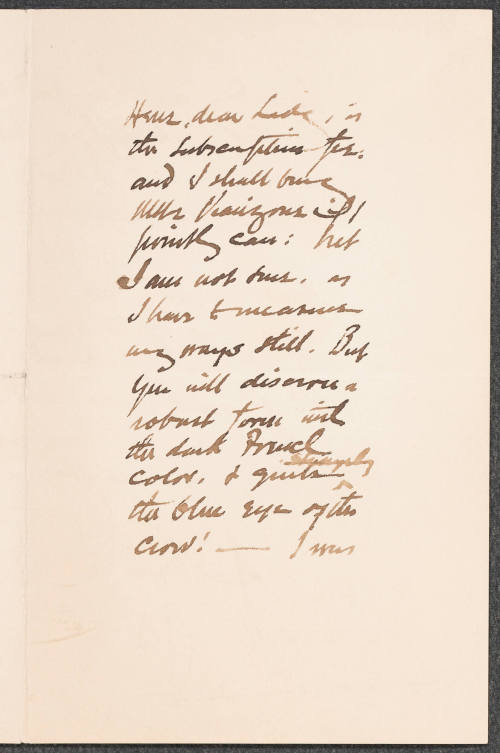

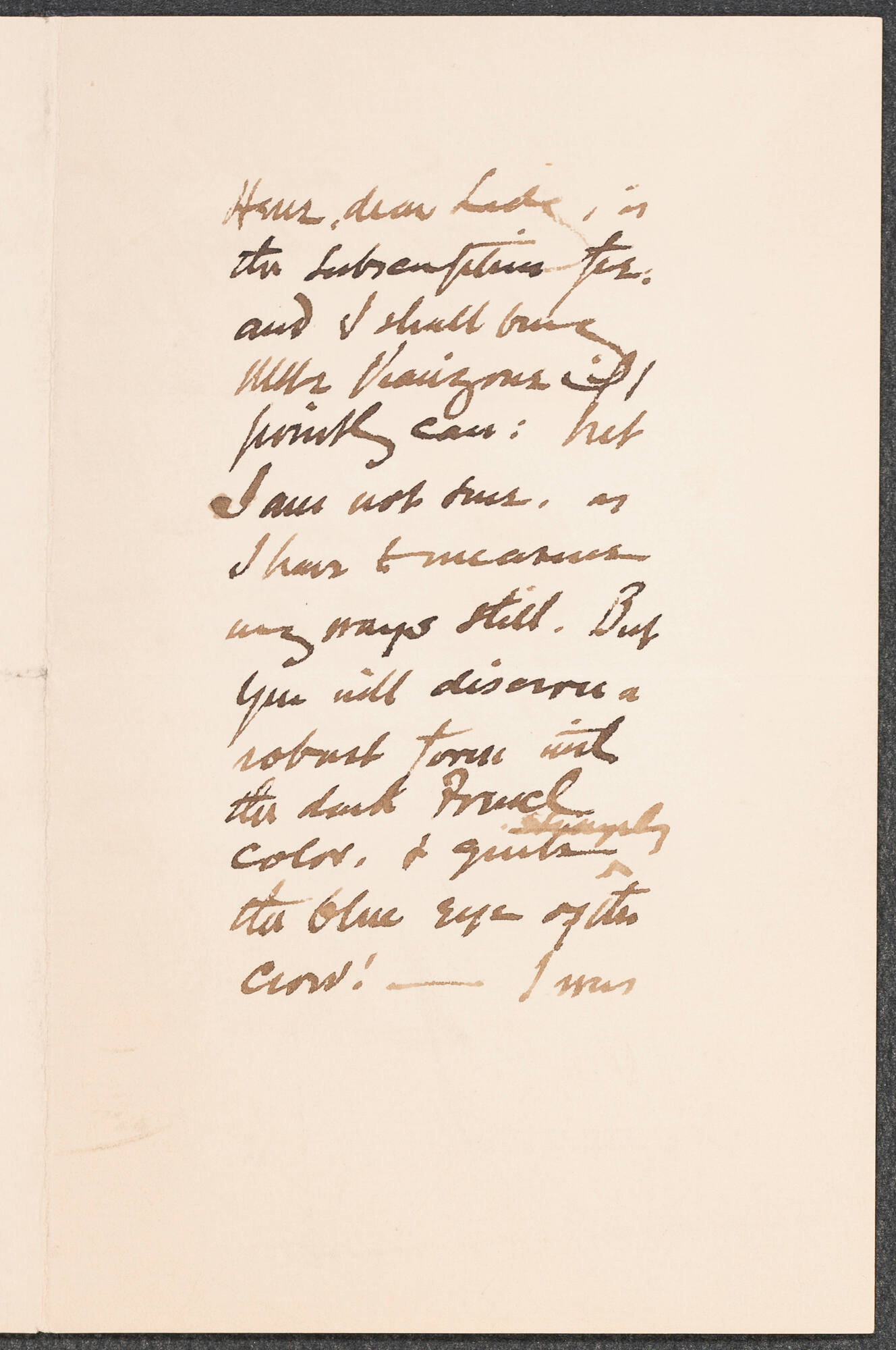

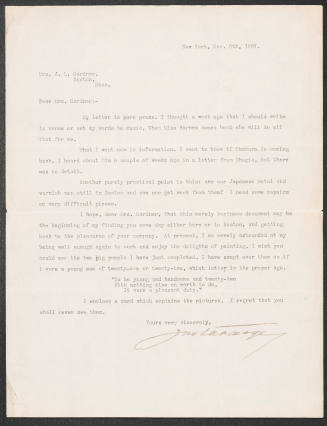

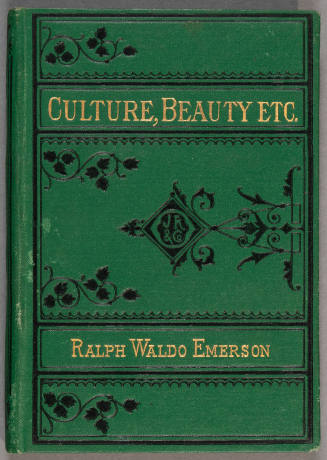

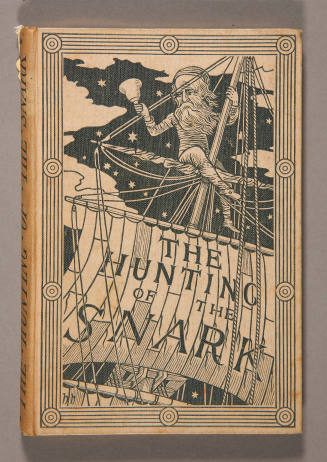

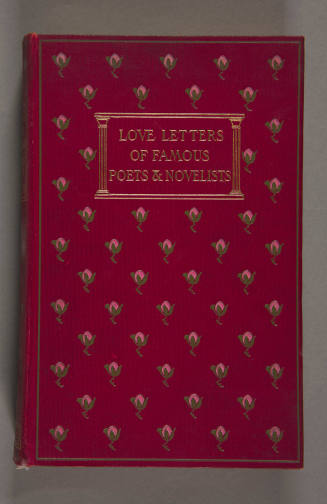

Whitman lived on Beacon Hill, and during this period she became closely associated with the circle of writers and artists gathered at 148 Charles Street, the home of Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett. The bookcover design for Verses by Sarah Chauncey Woolsey (pseudonym Susan Coolidge), a close friend of Fields and Jewett, started Whitman in 1880 on a long career as a stylist and designer of trade bookbindings. She designed books for many of the writers who were welcome at Charles Street, among them, James Russell Lowell, Amy Lowell, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and William Dean Howells. Whitman designed most of the bookcovers for Jewett, with whom she became very close and devoted. Jewett dedicated Strangers and Wayfarers to her in 1890.

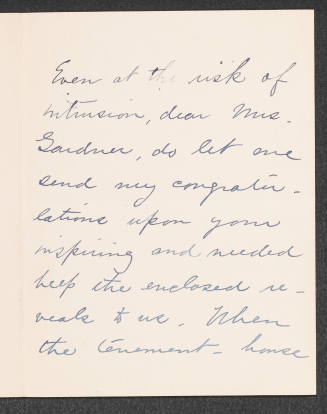

Working chiefly for Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Whitman stripped away the fussy clutter of bookcover designs of the period and brought to her work a spare elegance that reflected the influence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, James A. M. Whistler, and the growing popularity of Japanese fabric design. By 1887, with the publication of The Vision of Sir Launfall by James Russell Lowell, Houghton Mifflin began to capitalize on Whitman's name recognition as cover designer and began to feature her name prominently in their advertisements. By the mid-1890s Whitman was regarded as "the pioneer of designing for modern cloth covers," and her innovative designs ranked with those by William Morris, Walter Crane, Elihu Vedder, Stanford White, and others. Her distinctive lettering, an informal, vernacular style comparable to calligraphy, began to appear on almost every book issued by Riverside Press, a division of Houghton Mifflin noted for high standards of book form and printing. For the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 Whitman designed the Houghton Mifflin book pavilion.

Whitman's other driving interest was stained glass. Although there is no certainty about how she began or with whom she studied, it can be safely assumed that it was with John La Farge, a former student and friend of Hunt's and in 1877 the chief muralist and designer of stained glass for Trinity Church in Boston. Whitman's first known, major commission, in 1884-1885, to design the stained glass windows of Central Church (now United Church of Christ, Congregational) in Worcester, Massachusetts, may have come on the recommendation of La Farge, who was then "too busy to give the matter proper attention." Whitman personally supervised the work, from the design of the windows to the drawings for the wall decorations (now lost) to the handpainting (now lost) of scrollwork on the spandrels of the arches of the nave. It was an ambitious design program, a bold amalgam of traditional and nonconventional forms and painterly, striking colors, recalling the interior enrichment of Trinity Church. In 1886-1887 she received her second major church commission, to design the windows, organ case, and painted decorations for the apse (the apsidal windows and decorations are now lost) in Christ Church, Andover, Massachusetts. This commission reflected Whitman's personal approach to stained glass and interior design: quieter, more graceful and harmonious, stylistically closer in feeling and aesthetic to the school of William Morris in England. Although Whitman never fully and properly praised La Farge as the key figure in her development as designer and fabricator of stained glass, his fundamental conceptions of form, space, painterly color, and tone remained basic to her work.

In the 1890s Whitman did some of her finest work in stained glass, windows she designed and made in the Lily Glass Works, the studio she established in 1887. Among her crowning achievements were the Elizabeth Robbins Memorial Window, St. Ann's Church, Kennebunkport, Maine (1892); the windows in the Fogg Memorial Building, Berwick Academy, South Berwick, Maine (1890-1894); the Bishop Phillips Brooks Memorial Window, Parish House, Trinity Church, Boston (1895-1896); and the Martin Brimmer Memorial Window (1895-1898) and Honor & Peace (1896-1900), Memorial Hall, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Through years crowded with major commissions and soaring success, Whitman continued to paint and to exhibit her work. She won an honorable mention in the Paris Exposition of 1889 and had a third, one-woman exhibition at Boston's St. Botolph Club, a prominent men's club with exhibition space newly opened to local women artists. Also in 1889 Whitman painted her first known mural, The Heavenly Pilgrimage (now in storage), for Central Church. Recognition of Whitman's varied career came in November 1892 with an exhibition at Doll & Richards that brought together all aspects of her art, including her bookcover designs and stained glass; in December the exhibition moved to Avery Galleries in New York. In addition to the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Whitman participated in the 65th Annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy (1895-1896) in Philadelphia. She received another honorable mention at the Paris Exposition of 1900 and a Bronze Medal at the Pan-American Exposition held in Buffalo, New York, in 1901.

Despite the pressures of her work Whitman found time to explore other avenues of design: a silver goblet and pitcher (1892), a monument to Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes (1895), a plaque for the Hemenway Gym at Radcliffe (1897), and the plaque over the entrance to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (1900). She designed interiors for Radcliffe: Fay House (1885), Bertram Hall (1900), and Agassiz House (1902); the offices of Houghton Mifflin (1900-1901); and the Parkman School, Forest Hills (1903-1904). She also found time to compose sonnets, write about art history and bookcover design for young people, examine the nature of crafts, and promote the importance of art in the public schools.

Whitman's sense of social responsibility extended to the community. She taught Bible classes for thirty years at Trinity Church and during summers at Beverly Farms Baptist Church on the North Shore. She taught art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and was the first woman member on the Council of the School (1885). Her commitment to education, especially for women, led to her early involvement in the founding of Radcliffe College (1886). At the turn of the century Whitman was active in the formation of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts (1897), and she organized the Women's Auxiliary of the Massachusetts Civil Service Reform Association (1901).

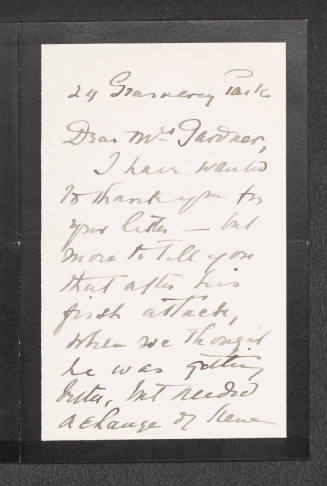

It was at this time, in 1900, that years of neglect took their toll and that Whitman's health began to fail. At her death in Boston, she was mourned by a large circle of friends. William James summed up the sense of loss in a letter to his brother Henry, "She leaves a dreadful vacuum in Boston." In a memorial address, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes spoke of her as "a woman worthy of public honor and loving pride." In the late fall of 1804 the Friends of Radcliffe College bought Whitman's last work in stained glass, made specially for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, held that year in St. Louis, "in commemoration of her services to the college and to the community in which she lived." (First placed in the newly opened Agassiz House, it was moved in 1907-1908 to what is now the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College.) Whitman was honored also with a memorial exhibition of her stained glass and bookcover designs by the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts (1905); a memorial loan exhibition of her paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts (1906); a paten given by Trinity Church women's Bible class (1906); a stained glass window installed in the Parish House, Trinity Church (c. 1910); and by the naming of the Whitman dormitory at Radcliffe College (1912).

By the 1920s Sarah Wyman Whitman's reputation had waned as the large, admiring circle of friends and patrons died and was replaced by a newer generation of artists and collectors as well as newer, avant-garde styles and tastes. The taste for Barbizon painters and the historicism of William Morris, his associates, and the Arts and Crafts movement were superseded by French impressionism. Whitman's work came to be viewed as old-fashioned and of uneven quality, the result no doubt of her having undertaken too much in order to satisfy her patrons.

Bibliography

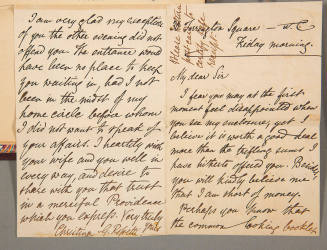

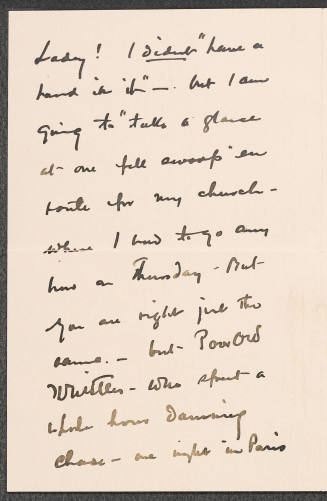

A miscellaneous collection of Whitman's letters, recollections, and notes is in the Radcliffe College Archives, Schlesinger Library, Cambridge, Mass. Houghton Library at Harvard University has personal correspondence both to and from Whitman as well as business letters and advertisements of her work covering nearly twenty years. Letters that best reveal Whitman's personality are in the "Constantia" letters (1887-1902) in the Fonthill manuscripts at the Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pa., and in Manibus O Date Lilia Plenis: Letters of Sarah Wyman Whitman (1907), a posthumous tribute edited by Sarah Orne Jewett. Another collection of letters, located in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (Reel D32), affirms the close friendship between Whitman and Martin Brimmer, the first president of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Whitman's approach to art and her work can best be described in "William Morris Hunt," International Review, Apr. 1880, pp. 389-401, her emotional tribute to her late teacher; "Stained Glass," Handicraft, Sept. 1903, pp. 117-31; "Cups," Handicraft, June 1902, pp. 57-60; "The Memorial Windows at Trinity Church," Church Militant, Jan. 1901, pp. 8-12-16; and Notes on an Informal Talk on Book Illustration Inside and Out . . . (1894). Her concern for art education is discussed in Notes of Three Composition Class Criticisms by Mrs. Henry Whitman, Mr. Arthur Dow, and Mr. I. M. Gaugengigi (Boston Art Students Association, 1893); The Making of Pictures: Twelve Short Talks with Young People (1886); and "The Pursuit of Art in America," International Review, Jan. 1882, pp. 10-17. Martha J. Hoppin, "Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1900: The Pupils of William Morris Hunt," American Art Journal 13, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 17-46, is a significant source of information about the careers of Hunt's pupils. John Chapman, "Mrs. Whitman," in Memories and Milestones (1915), is an effusive essay that attempts to capture Whitman's personality. The stained glass windows in Memorial Hall at Harvard University caught the attention of Annie Fields, "Notes on Glass Decoration," Atlantic Monthly, June 1899, pp. 807-11, and Mason Hammond, The Stained Glass Windows in Memorial Hall, Harvard University (1978; rev. ed., 1983). Obituaries are in the Boston Sunday Herald, 26 June 1904, and the Boston Evening Transcript, 27 June 1904. The record of the memorial service held at the Beverly Farms Baptist Church on 17 July 1904 was published by Merrymount Press, Boston. The Women's Auxiliary of the Massachusetts Civil Service Reform Association (July 1904), the Public School Art League (Nov. 1904), the Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin (Sept. 1904), and the American Art Annual (1905-1906) were among the organizations that formally recognized her passing.

Betty S. Smith

Back to the top

Citation:

Betty S. Smith. "Whitman, Sarah de St. Prix Wyman";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00927.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:52:50 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts, 1848 - 1906

American, 1870 - 1885

London, 1830 - 1894, London

Stockbridge, Massachusetts, 1862 - 1929, Clifton Springs, New York

Edinburgh, 1811 - 1890, Aryshire, Scotland

Paisley, Scotland, 1855 - 1905, Syracuse, Sicily