William Rothenstein

Bradford, Yorkshire, 1872 - 1945, Far Oakridge

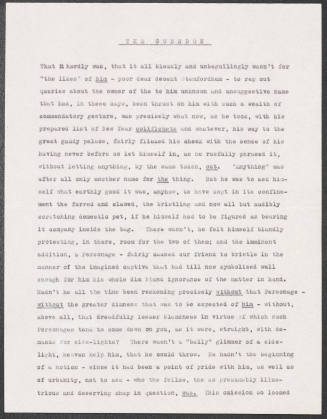

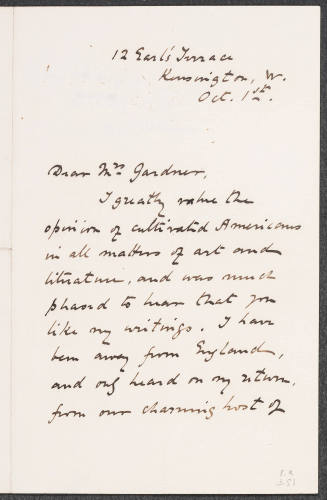

That reputation preceded Rothenstein to Oxford when the publisher John Lane commissioned him to produce a volume of lithographic portraits of Oxford personalities, Oxford Characters, to coincide with Max Beerbohm's Caricatures of Twenty-Five Gentlemen (both 1896). Rothenstein's advent inspired Beerbohm's description of him in his Seven Men (1919): ‘He was a wit. He was brimful of ideas. He knew Whistler. He knew Edmond de Goncourt. He knew everyone in Paris. He knew them all by heart. He was Paris in Oxford’ (Beerbohm, 3). With the publication of Oxford Characters Rothenstein met Aubrey Beardsley, Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, and Augustus John. Other volumes followed, the most notable being English Portraits (1898), which included Thomas Hardy, George Gissing, Robert Bridges, A. W. Pinero, Cunninghame Graham, Grant Allen, William Archer, and Henry James, with letterpress by Beerbohm and others. The French coastal landscape became Rothenstein's favourite subject for both drawings and oils and Vattetot, near Dieppe, a favourite gathering place for William, his younger brother Albert Rutherston (1881–1953), also a London artist, and New English Art Club friends.

On 11 June 1899 Rothenstein married Alice Mary Knewstub (1869–1955), who had appeared on the stage as Alice Kingsley. They had two sons, Sir John Knewstub Maurice Rothenstein (1901–1992), who became director of the Tate Gallery, and (William) Michael Francis Rothenstein (1908–1993), artist and designer, and two daughters, Rachel and Betty.

In 1903, after a chance visit to the Spitalfields Great Synagogue in east London, which served the large immigrant community from eastern Europe, and where Rothenstein first saw Orthodox Jews at prayer and study, he began his eight Synagogue Paintings. He rented a studio near by and persuaded synagogue members to sit to him, re-creating scenes of Jewish religious life. Of the eight paintings, three remained in England, one went to Melbourne, Australia, and one to Johannesburg, South Africa, and three (together with many of the accompanying studies and drawings) remain unaccounted for.

With time, Rothenstein became increasingly uncomfortable about his relations with some members of the New English Art Club, who found him too unyielding about the nature and function of art. He thought them unsympathetic towards both his painting and his views: even in his blithe and busy years in Paris he had been serious about art and during the early 1900s he became markedly more so. His greater intensity and earnestness were evident in his habitual dissatisfaction with his own work, his fears about loss of facility in draughtsmanship, and his concern over the spiritual content both in his own work and that of his colleagues. He withdrew from the New English Art Club and rejected a nomination (submitted without his knowledge) for his election to associate membership of the Royal Academy. Although he was honoured, he felt it dishonest to belong to a body of whose policy he disapproved.

When H. A. L. Fisher suggested in 1909 that Rothenstein should apply for the Slade professorship of fine art at Oxford, he hesitated because he would compete directly with Roger Fry, who he knew wanted the post. Fisher advised Rothenstein to leave his name in nomination and withdraw if the choice were between himself and Fry. If for the next appointment Oxford wanted a practising artist instead of a critic, Rothenstein's name could remain in consideration as candidate. However, neither he nor Fry was chosen; the matter remained literally academic.

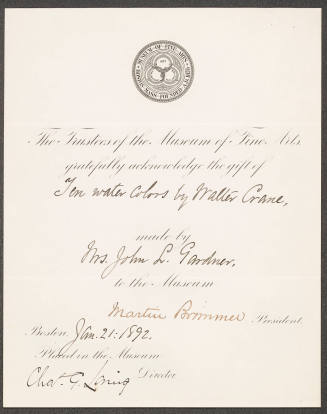

In January 1910 his earnestness had important and lasting international effect when, with Walter Crane and Ananda Coomaraswamy, Rothenstein went to the Royal Society of Arts in support of Ernest Havell, retired principal of the Government School of Art in Calcutta, who protested against the school's policy for teaching Indian students, whose training consisted of copying classical casts and mediocre European art to the exclusion of indigenous design and motifs. Sir George Birdwood, a former curator of the Government Museum in Bombay and a founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum in that city, declared that India had no fine arts and that the figure of the Buddha was no more spiritual than a boiled suet pudding. Outraged, Rothenstein, who was already interested in Mughal painting, founded, together with Havell, in 1910, an India Society to educate the British public about Indian arts. In the winter of 1910–11 he went to India with the painter Christiana Herringham, who had been copying the rapidly deteriorating Buddhist wall-paintings in the Ajanta caves in central India. In Calcutta he met the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, whom he introduced to literary and artistic circles in London in 1912. Rothenstein was instrumental in the publication by the India Society of translations of Tagore's Bengali lyrics Gitanjali (Song-Offerings), for which he was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1913, the first such award to an Asian. The influence of Indian art led to changes in Rothenstein's own painting: enamoured of the mass and solidity of Indian architecture, his own Indian scenes became heavier in style where formerly they had been light and delicate.

Rothenstein was in India when Roger Fry's first post-impressionist exhibition created a sensation at the Grafton Galleries in London in November 1910. Unimpressed by post-impressionism, he feared that its sudden excessive publicity would seduce younger artists from ‘more personal, more scrupulous work’ (Rothenstein, Men and Memories, 2.219). Although he agreed to work with Fry on a second exhibition, crossed letters and misunderstandings ultimately prevented their co-operation. While Fry became an advocate of post-impressionism, Rothenstein was increasingly in demand as a lecturer, and he turned his attention to philosophical questions concerning the meaning of art, the function of art schools and museums, the artist's role in an industrial culture, and, in the decline of personal patronage, the importance of generating municipal support for artists and craftsmen.

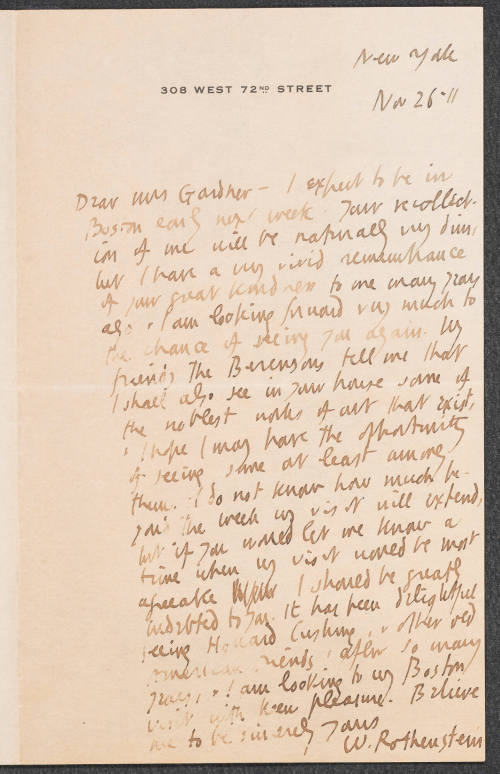

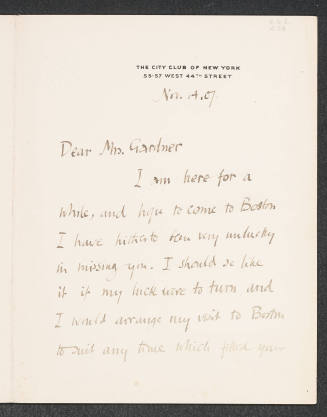

After his return from India, and an American tour in 1911, Rothenstein and his wife moved to Iles Farm, Far Oakridge, near Bisley, Gloucestershire, though they kept their flat in Hampstead. The mellow Cotswold stone and the local craftsmen who made furniture and fittings for their old farmhouse became the subject of Rothenstein's paintings at this time.

On the outbreak of war in 1914 the Rothensteins were affected by prejudice towards German names. With his brothers Charles (who carried on the family business in Bradford) and Albert, Rothenstein decided to change the family name to Rutherston. At the moment of legal commitment, William decided that the change meant too great a sacrifice of continuity and identity, and he alone, of his family, continued to carry the name of Rothenstein. Through Charles à Court Repington he approached the War Office in 1916 with a proposal that official war artists make (as the Germans were doing) an artistic record of soldiers and scenes of action. After much bureaucratic delay, the plan was approved, though he had little hope, in view of his German name, of being appointed an official war artist. In December 1917 he was finally allowed to go to the western front, where indeed his name did cause some difficulty. Painting as close to the front lines as he could get, he was at one point mistakenly arrested as a spy. Many of his battle scenes painted both before and after the armistice are in the collections of the Imperial War Museum in London.

In 1917 H. A. L. Fisher, then vice-chancellor of Sheffield University, persuaded Rothenstein to accept the university's new chair of civic art, the first of its kind in England, and an ideal position in which to pursue his interest in the philosophical aspects and civic uses of art. After the war the Rothensteins returned to London, and in 1919 Fisher, then president of the Board of Education, appointed Rothenstein visitor to the Royal College of Art, London, with a brief to report on its teaching methods and ethos. It was Fisher's long-held belief that art schools prepared art-school teachers instead of artists, and he considered it essential to restore the old pupil–master relationship. Rothenstein's report found that the separation between training and employment for artists on the one hand, and for designers and industrial craftsmen on the other, was imbalanced, and advised that art training should encourage experimentation and flexibility for both. Fisher then appointed Rothenstein, a painter without an art diploma, as principal of the college, a decision which drew forth strong protest from the National Society of Art Masters. By keeping a studio in the college where he worked two days a week, Rothenstein emphasized the importance he attached to the role of practising artist within the teaching of an art school. When asked for advice by the Federation of British Industries, he arranged for students to be taken on as paid apprentices, and the college created a new lectureship in industrial design.

Rothenstein had a remarkable ability to recognize genius in artists whose styles differed radically from his own. In 1907 George Bernard Shaw (who personally thought that Jacob Epstein's drawings looked like burnt furze-bushes) sent the sculptor to Rothenstein, who obtained on his behalf a grant from the Jewish Aid Society. When Epstein's sculptures for the British Medical Association building in London aroused allegations of obscenity, Rothenstein helped to mobilize support for his work. In 1908 he helped to obtain similar aid for the painter Mark Gertler and recommended him for a Slade scholarship. In 1922, when Henry Moore arrived at the Royal College of Art, Rothenstein overrode his colleagues' objections and engaged him as a teaching assistant. Following a day of heavy criticism of his work by teaching staff, Moore, on returning late to the college, found Rothenstein waiting to say that he must not allow himself to be swayed by such criticism but must continue in his chosen direction.

In 1925 Rothenstein's doctors discovered that he had a heart condition. During convalescence Rothenstein wrote Men and Memories (1931–2) and Since Fifty (1939), a treasure trove of information about art and artists since the 1890s. He was knighted in 1931 for services to art and in 1934 received the honorary degree of DLitt from Oxford University. A number of his works were acquired for the Tate Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery in London. When the Second World War began, Rothenstein again offered his services as a war artist, though poor health kept him from going abroad. Instead he made portrait drawings of airmen at RAF bases in England, many the last likenesses of those who did not return. (The Imperial War Museum, London, and the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon, Middlesex, have many of these in their collections.) In the last year of the war his health declined again; he died at Far Oakridge on 14 February 1945 and was buried at St Bartholomew's Church, Oakridge, Gloucestershire. On 6 March a memorial service for Rothenstein was held at St Martin-in-the-Fields in London; in his tribute to the painter Max Beerbohm acknowledged that Rothenstein had been ‘assuredly a giver, a giver with both hands, in the grand manner’ (Speaight, 410).

Mary Lago

Sources

W. Rothenstein, Men and memories: recollections of William Rothenstein, 2 vols. (1931–2) · W. Rothenstein, Since fifty: men and memories, 1922–1938 (1939) · W. Rothenstein, Men and memories: recollections, 1872–1938, of William Rothenstein, ed. M. Lago, abridged edn (1978) · M. Beerbohm, ‘Enoch Soames’, Seven men (1919) · Max and Will: Max Beerbohm and William Rothenstein, their friendship and letters, 1893 to 1945, ed. M. Lago and K. Beckson (1975) · Imperfect encounter: letters of William Rothenstein and Rabindranath Tagore, 1911–1941, ed. M. Lago (1972) · M. Lago, Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian art scene (1996) · R. Speaight, William Rothenstein: the portrait of an artist in his time (1962) · E. B. Havell, ‘Art administration in India’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 58 (1909–10), 274–85, esp. 290–91 · Henry Moore to Gilbert and George: modern British art from the Tate Gallery (1973) [exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, 28 Sept – 17 Nov 1973] · J. Rothenstein, Modern English painters, 1–2 (1952–6) · J. Rothenstein, The portrait drawings of William Rothenstein, 1889–1925 (1926) · Royal Air Force Museum, Sir William Rothenstein: a catalogue of the Royal Air Force Museum's collection (1989) · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1946) · WWW

Archives

BL OIOC, corresp. relating to Indian art, MS Eur. B 213 · Harvard U., corresp. and papers · Tate collection, notebooks and drafts for autobiography · Tate collection, corresp. and papers; study collection of drawings, lithographs, and sketches · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., corresp. :: BL, corresp. with G. K. Chesterton and F. A. Chesterton, Add. MSS 73239, fols. 151–64; 73454, fols. 83, 108 · BL, corresp. with Sir Sydney Cockerell, Add. MS 52750 · BL, corresp. with Macmillans, Add. MS 55232 · BL, letters to Albert Mansbridge, Add. MS 65253 · Bodl. Oxf., letters to H. A. L. Fisher · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with Gilbert Murray · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with E. J. Thompson · King's AC Cam., letters to Roger Fry · LUL, letters to T. S. Moore · Merton Oxf., Beerbohm MSS · NL Scot., letters to R. B. Cunninghame Graham · NL Wales, corresp. with Thomas Jones · Ransom HRC, corresp. with John Lane · U. Birm. L., letters to M. H. Spielmann · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Sir Edmund Gosse

Likenesses

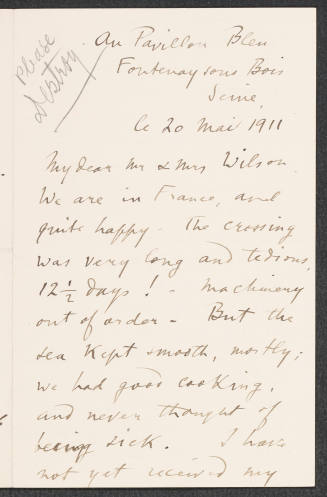

W. Rothenstein, self-portraits, oils, c.1890, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield · photographs, 1894–1940, NPG · J. S. Sargent, lithograph, 1897, BM, NPG · H. Tonks, group portrait, 1903 (with family), Athenaeum, London · A. John, oils, c.1904, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool · W. Rothenstein, self-portrait, oils, c.1906, Cartwright Memorial Gallery, Bradford · W. Rothenstein, self-portrait, oils, 1917, Carlisle City Art Gallery · M. Beerbohm, caricature, 1924 (The old and the young self), priv. coll. · W. Rothenstein, self-portrait, oils, 1930, NPG [see illus.] · M. Beerbohm, caricature, V&A · E. Dulac, pencil sketch, Royal Air Force Museum, London · A. K. Lawrence, charcoal and pencil drawing, Athenaeum, London · W. Orpen, oils (The selecting jury of the New English Art Club, 1909), NPG · W. Orpen, pencil, pen, ink, and watercolour drawing, NPG · W. Rothenstein, self-portrait (aged eighteen), priv. coll. · W. Rothenstein, self-portraits, drawings, NPG · A. Rutherston, ink and wash drawing, Man. City Gall. · H. Tonks, pencil and watercolour caricature (as Sancho Panza), BM

Wealth at death

£22,497 15s. 3d.: probate, 18 Jan 1946, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Mary Lago, ‘Rothenstein, Sir William (1872–1945)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2013 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35842, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Sir William Rothenstein (1872–1945): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35842

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Brighton, 1872 - 1898, Menton, France

Ledbury, England, 1878 - 1967, near Abingdon, England

Alnwick, Northumberland, 1840 - 1922, London