Okakura Kakuzo

Okakura Kakuzo (23 Dec. 1862-2 Sept. 1913), art historian, connoisseur, and author of The Book of Tea, was born in Yokohama, Japan, the son of Okakura Kanemon, a silk merchant and former samurai, and his wife, Kono. His eclectic upbringing and gift for languages fitted "Tenshin" (or "heart of heaven," the honorific name by which Okakura is known to the Japanese) for the role of cultural ambassador to the West. Okakura and his younger brother Yoshisaburo (later a professor of English and for a time a translator for Lafcadio Hearn) learned English at the local Christian mission school of Dr. James Hepburn, the inventor of the system for Romanization of Japanese words that is still in use. Okakura also studied classical Chinese at a Buddhist temple. An arranged marriage with Motoko Ooka took place in 1879; the couple would later have a son and a daughter.

Okakura graduated in 1880 from the Faculty of Letters at the newly founded Tokyo Imperial University, where he studied with Ernest Fenollosa, a leader in the effort to preserve traditional Japanese arts in the face of the Westernizing Meiji government. Inspired by Fenollosa, Okakura published in 1882 a defense of calligraphy as a fine art. Fenollosa and Okakura carried out an extensive government-sponsored survey of the art collections of Buddhist temples. In 1886 the two men were appointed to the Imperial Commission of Enquiry to study methods of art education in Europe and the United States with a view toward establishing a national art academy in Japan. In his own writings and speeches, Okakura marked out a middle path between unquestioning preservation of Japanese traditions and the wholesale adoption of "European" methods and ideas. "Conformity is the domicile of bad habits," he wrote. "Art is a product of past history combined with present conditions. It develops from this fusion of past and present."

During the summer of 1886, the historian Henry Adams and the painter John La Farge visited Japan. Their hosts were Fenollosa, Okakura, and Dr. William Sturgis Bigelow (a significant collector and benefactor of the Japan collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). That fall, Okakura and Fenollosa joined Adams and La Farge on their return journey, to begin their official tour of Western art institutions. Through his close personal friendship with La Farge, Okakura helped develop the fusion of Japanese and Western motifs that emerged in such impressive works as La Farge's Church of the Ascension mural in New York City (where the background is a Japanese mountain landscape) and the Adams Memorial in Washington by the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The latter was designed for the grave of Henry Adams's wife, Clover, who had committed suicide just before the Japan journey, and draws on Japanese conceptions of Kannon, the Buddhist deity of mercy.

After his return to Japan, Okakura rose rapidly in the arts establishment. In 1890, at the age of twenty-seven, he became director of the new Tokyo Art School (now the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music), which he led for eight years. He also served as curator of art at the Imperial Museum (now the Tokyo National Museum) and helped conceive the Japanese pavilion for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Political and personal troubles, including his affair with the wife of a prominent colleague in the Ministry of Education, led to Okakura's resignation from his official posts. Many of his teachers joined him in the founding of an alternative private art school, the Japan Art Institute. Several of Japan's leading modern painters, including Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunso, emerged from this school.

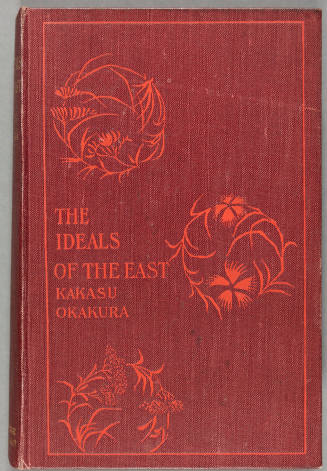

Okakura traveled to India in 1901, where he lived with the family of the Bengali poet, Nobel-prize winner, and partisan Rabindranath Tagore. This was the beginning of a new phase in Okakura's career: twelve years of nomadic wandering as international celebrity and writer of books for the English-speaking public. In India, Okakura drafted his first book in English, The Ideals of the East (1903), which opens with the famous and often quoted line: "Asia is one." On 10 February 1904, the day that Japan entered a war with Russia, Okakura boarded a ship in Yokohama bound for the United States. Dr. Bigelow, aware of Okakura's difficulties in Japan, had arranged for him to work as an adviser on Chinese and Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the department that Fenollosa had established in 1890. In September 1904 Okakura lectured on Japanese art at the St. Louis World's Fair.

From 1904 until his death in 1913, Okakura worked at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, then and now the most comprehensive repository of Japanese art outside Japan. In collecting ancient ritual jade implements and Taoist sculptures and paintings, Okakura went far beyond his contemporaries' taste for export porcelain, and his policy of filling gaps in the collection remains in place today. During this period, Okakura emerged as the very embodiment of Japan in dress and deportment, in the Boston of his close friend and patron, Isabella Stewart Gardner, who had just opened her eclectic museum on the Fenway. Gardner told Mary Berenson that Okakura was "the first person . . . who showed her how hateful she was, and from him she learnt her first lesson of seeking to love instead of to be loved."

In November 1904 Okakura published his second book in English, The Awakening of Japan. Nationalistic in tone and argument, the book celebrates Japanese prowess in the arts and on the battlefield. These themes recur in The Book of Tea (1906), Okakura's most popular book in English. Okakura linked Western incomprehension of the tea ceremony to the recently completed Russo-Japanese War. "The average Westerner . . . will see in the tea ceremony but another instance of the thousand and one oddities which constitute the quaintness and childishness of the East to him. He was wont to regard Japan as barbarous while she indulged in the gentle arts of peace; he calls her civilized since she began to commit wholesale slaughter on Manchurian battlefields." Okakura's philosophy of the "imperfect" and his sustained attack on "uniformity of design" are aspects of the wabi aesthetic of rustic poverty. This wabi taste for thatched roofs and unfinished beams was congruent with the American Arts and Crafts aesthetic--what Thorstein Veblen called in The Theory of the Leisure Class "the exaltation of the defective." Frank Lloyd Wright specified that it was in The Book of Tea that he first came across the idea of interior space that inspired his own "architecture of within."

Okakura's final years were marked by ill health, though he continued to travel to Japan and China in search of objects for the Museum of Fine Arts. In 1911 he was awarded an honorary degree from Harvard. Okakura's final months were spent completing an opera libretto called "The White Fox," about a vixen who takes human form to impersonate the lost love of her benefactor. Okakura died at age fifty of kidney failure in the mountain village of Akakura, northwest of Tokyo.

Bibliography

The major source for Okakura's books, articles, and correspondence is Okakura Kakuzo: Collected English Writings (1984), published by Heibonsha in Japan. The Book of Tea is available in several different editions. Yasuko Horioka, The Life of Kakuzo (1963), is published by Hokuseido in Japan. The catalog for an exhibition entitled Okakura Tenshin and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (2000)--especially the article by Anne Nishimura Morse, "Promoting Authenticity: Okakura Kakuzo and the Japanese Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston"--includes important information on Okakura as collector and connoisseur. "Tea with Okakura," by Christopher Benfey, New York Review of Books, 25 May 2000, pp. 43-47, provides an overview of Okakura's career. Stephen N. Hay, Asian Ideas of East and West: Tagore and His Critics in Japan, China, and India (1970), explores the friendship between Okakura and Tagore. Kevin Nute, Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan (1993), details Okakura's influence on Wright. For Okakura's relationship with Isabella Gardner, see Douglass Shand-Tucci, The Art of Scandal: The Life and Times of Isabella Stewart Gardner (1997). An obituary by William Sturgis Bigelow and John Ellerton Lodge, "Okakura-Kakuzo 1862-1913," appeared in Museum of Fine Arts [Boston] Bulletin 11, no. 67 (Dec. 1913): 72-75.

Christopher Benfey

Back to the top

Source:

Christopher Benfey. "Okakura Kakuzo";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-01634.html;

American National Biography Online April 2001 Update.

Access Date: Mon Jul 29 2013 16:01:52 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

Okakura, Tenshin [Kakuz]

Date born: 1863

Place Born: Yokohama, Japan

Date died: 1913

Place died: Niigata Prefect, Japan

Museum curator and historian of Japanese painting. After graduating from Tokyo Imperial University in 1880, Okakura became a member of the Ministry of Education. His interests later turned to art education, allowing him to travel to Europe and America to do research on art education methods. Upon his return to Japan, Okakura was appointed head of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. His leadership encouraged artists to develop a new style of painting that combined the conventional style of the Japanese painting technique Nihonga with Western realism. After resigning from the School of Fine Arts in 1898, Okakura created the Japan Art Institute. His interest in Western painting, and his knowledge of Japanese painting styles led Okakura to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where he served as both an advisor and as the head of the East Asian department. LMW

Home Country: Japan

Sources: The Dictionary of Art

Bibliography: The Ideals of the East: with Special Reference to the Art of Japan. London: J. Murray, 1920; The Awakening of Japan. New York: Special ed. for Japan Society, Inc., 1921.

Source:

http://www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/kokakurat.htm