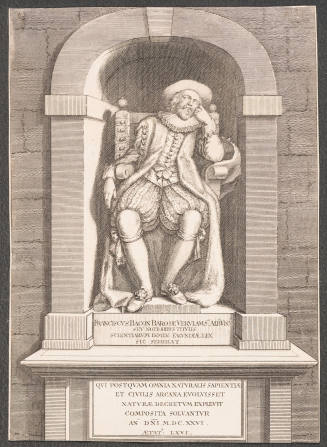

Francis Bacon

Bacon, Francis, Viscount St Alban (1561–1626), lord chancellor, politician, and philosopher, was born on 22 January 1561 at York House in the Strand, London, the second of the two sons of Sir Nicholas Bacon (1510–1579), lord keeper, and his second wife, Anne (c.1528–1610) [see Bacon, Anne], daughter of Sir Anthony Cooke, tutor to Edward VI, and his wife, Anne, née Fitzwilliam. He was baptized in the local church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, but spent most of his childhood, together with his elder brother, Anthony Bacon (1558–1601), at Gorhambury, near St Albans, Hertfordshire, which their father had purchased in 1557. In the 1560s Nicholas Bacon built a new house there, and this house (together with Verulam House, which Francis Bacon built nearby later in his life) became one of his three central emotional places (the other two being York House where he again lived, as lord keeper and lord chancellor later in his life, and Gray's Inn, where he lived for most of his life). The well-known story that Elizabeth I often referred to Francis as ‘the young Lord-Keeper’ is presumably no more than a legend.

Early years and education

Bacon received his early education at home. Judging by their own experiences his parents must have set great store by education. In Nicholas Bacon's career from a sheep-reeve's son to lord keeper schooling had been crucial. His second wife's learning matched his own: her father, Sir Anthony Cooke, had inculcated classical erudition and protestant piety in his five daughters, and Anne Bacon was fluent in Greek and Latin as well as in Italian and French. Her erudition and piety were put to good use when, during Francis's infancy, she translated John Jewel's Apologia ecclesiae Anglicanae into English.

The chaplains who served the Bacon household had strong leanings towards puritanism. One, John Walsall, a graduate of Christ Church, Oxford, acted as the sons' tutor from 1566 to at least 1569. By this time the Bacon brothers were joined in the schoolroom at Gorhambury by Sir Thomas Gresham's illegitimate daughter, who had just married their half-brother, Nathaniel Bacon. When she returned home she wrote a letter of thanks to Anne, Lady Bacon, including regards for ‘my brother Anthony and my good brother Frank’ (R. Tittler, Nicholas Bacon, 1976, 156). Although there is no direct evidence there is little doubt that Bacon went through the whole of the normal primary and grammar school curriculum at home. His schooling not only included Christian teaching but also thorough training in the classics.

Having provided seven or eight years' education for his youngest sons at home Sir Nicholas Bacon sent them to university. All his sons went to Trinity College, Cambridge. Anthony and Francis (who had just turned twelve) went up to Cambridge on 5 April 1573 and matriculated on 10 June. They stayed there until December 1575, although their period of residence was twice interrupted when plague broke out in the Cambridge area. At Trinity the brothers, with their companion Edward Tyrell, one of Sir Nicholas's wards, were put under the personal tutelage of the master, Dr John Whitgift, the future archbishop of Canterbury. From these years at Cambridge dates Bacon's earliest extant letter. It is a request addressed on 3 July 1574 to his half-brother Nicholas Bacon, who had promised to send a deer for the graduation of Nicholas Sharpe, a fellow Trinity member.

According to the accounts kept by Whitgift he bought for the Bacon brothers' use the major classical texts and commentaries. These included the Iliad, Plato and Aristotle, ‘tullies workes’ (perhaps Cicero's philosophical works and letters), Cicero's rhetorical works, Demosthenes' Orations, Hermogenes' Ars rhetorica in a facing-page Greek and Latin edition, as well as the histories of Livy, Sallust, and Xenophon (P. Gaskell, ‘Books bought by Whitgift's pupils in the 1570s’, Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 7, 1979, 284–93).

Bacon's education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. But the impact of humanism had drastically changed the way in which this curriculum was taught. A particular emphasis was placed on practical problems at the expense of logical subtlety. As is evident from the books Bacon purchased in Cambridge there was a strong emphasis on philosophy, rhetoric, and history in his studies. This was a particularly typical feature of Renaissance humanism, whose main aim was to train youth for public life.

The next step for a gentleman intending a public career was entrance to the inns of court. Francis Bacon was entered at Gray's Inn on 27 June 1576 and was admitted in November. Meanwhile, however, he was sent to France to accompany Sir Amias Paulet, English ambassador to France. Originally both Francis and his half-brother Edward were to go, but in the end only Francis followed Paulet late in September 1576, whereas Edward travelled on his own, heading not only to protestant centres like Geneva and Strasbourg but also to Vienna, Venice, and Padua.

Travelling abroad was considered highly useful to a young gentleman's education—an opportunity for learning foreign languages and finding out about customs, politics, and institutions. But Bacon's stay in France (mostly in Paris, Poitiers, and Blois), which lasted almost exactly two and a half years, was not so much an educative grand tour. While he studied language, statecraft, and the civil law most of his time was presumably spent in performing routine diplomatic tasks.

When Bacon went to France he was only fifteen, and shared with Paulet's sons a tutor named Mr Duncumbe. When Duncumbe returned to England in October 1577 he was replaced by Jean Hotman, the son of the well-known Huguenot François Hotman. In 1578 Bacon was placed in the household of a civil lawyer to acquire a deeper acquaintance with civil law, then very important in diplomacy. This early exposure to Roman law had presumably a profound influence on his legal thinking, and when later in life Bacon developed his ideas of legal reform the impact of the Roman civil law was especially marked.

During his stay in France, perhaps in autumn 1577, Bacon once visited England as the bearer of the diplomatic post, delivering letters to Walsingham, Burghley, and Leicester and to the queen herself. Fairly soon after his return to France he planned a trip to Italy but Paulet did not grant him permission, mainly on religious grounds (Jardine and Stewart, 61–3).

Bacon's stay in France came to an abrupt end a few months before it was scheduled when the news of his father's death in February 1579 reached him. The youngest son made haste and arrived in London within a month of this event. He also brought the diplomatic post from Paulet, which included a recommendation from Sir Amias to the queen: ‘Mr. Francis Bacon, is of great hope, endowed with many good and singular parts; and if God give him life will prove a very able and sufficient subject to do your Highness good and acceptable service’ (Jardine and Stewart, 66).

His father's sudden death was a serious setback for Francis Bacon. Sir Nicholas had settled estates for all of his other sons and was in the course of doing so for the youngest one when he died. Moreover, Sir Nicholas's two families contested his will, and although an agreement was eventually reached with the help of Lord Burghley the half-brothers were never again close. The situation was worst for the youngest son, who had neither land nor income nor even a position.

Aged eighteen Bacon resumed his studies in Gray's Inn. Sir Nicholas had been a central figure in Gray's Inn and all his sons had been admitted there, but Francis was the only one who took up law as a profession. As a law student he was expected to attend readings or series of formal lectures on a specific English statute, to participate in hypothetical legal situations and thereby to learn cases, and to argue in moot courts (to argue on both sides of a case). Whether it was due to his natural talents or the seriousness with which he pursued his studies Bacon made rapid progress. He was admitted to the bar as an utter barrister of Gray's Inn (the equivalent of graduation) in June 1582, became bencher in 1586 and in November 1587 was elected as a reader, delivering his first set of lectures on church advowsons in Lent 1588.

Early career

While still pursuing his legal studies Bacon embarked on a public career. He sought the help of his uncle, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, and his aunt, Lady Burghley [see Cecil, Mildred], in September 1580, commending his earlier suit, which Burghley had promised to forward to the queen, and calling Burghley ‘my patron’. By October Burghley informed him of ‘her Majesty's gracious opinion and meaning towards’ him (Works, 8.13–14). When the duke of Alençon visited England in December 1580 Bacon was employed as a translator.

By the time the third and last session of the parliament, originally elected in 1572, met in January 1581 many by-elections had taken place. Among the new members was Francis Bacon, who had his twentieth birthday during the session. He sat for Bossiney, Cornwall, which was controlled by his godfather, the earl of Bedford. There is no evidence of Bacon's activities in this session. In the parliament of 1584 Lord Burghley won him a seat (Gatton, Surrey), but Bacon preferred the earl of Bedford's patronage, sitting for Weymouth and Melcombe Regis, Dorset. He was named to one committee and made his maiden speech on a bill concerning wards.

Bacon showed signs of sympathy to puritanism, not only attending the sermons of the puritan chaplain of Gray's Inn, but also accompanying his mother to the Temple chapel to hear the even more staunchly puritan sermons of Walter Travers. By 1584 Bacon, together with many key figures in the political nation, had become alarmed by both the perceived growing Catholic threat and the English church's suppression of the puritan clergy. He joined many others in critically reviewing in a tract this anti-puritan campaign led by his former tutor, recently appointed archbishop of Canterbury, John Whitgift, who demanded absolute submission to the church's discipline from the entire clergy.

Bacon's tract is his earliest extant longer writing and was obviously widely circulated. He strongly criticized the Catholics both within and without England and gave support for the puritan cause. But his argument was couched in strongly political terms. He appealed to ‘all reason of state’ and to the example ‘of the most wise, most politic, and best governed estates’. For the danger within the queen should do everything possible to strengthen protestantism, mainly through promoting preaching and schooling, because all her ‘force and strength and power’ consisted in her protestant subjects. As for the problems without, the best remedy was a political alliance with the enemies of Spain, above all with Venice and the Netherlands (Works, 8.47–56).

In 1585 Bacon felt that his age (twenty-four) blocked the advancement of his career. He requested Burghley's help with his career at Gray's Inn, and asked Sir Christopher Hatton and Sir Francis Walsingham to advance his suit for a political office. Although no office was forthcoming various other employments kept him busy. Through Walsingham's patronage Bacon was soon employed to investigate English Catholics. In the parliament which met in winter 1586–7 Bacon (sitting for Taunton, Somerset) was more visible than before. He argued for the execution of Mary, queen of Scots, and was named to the committee appointed to draw up a petition for her execution. He also spoke in favour of the proposed subsidy and sat on three other committees. In September 1587 the privy council consulted the attorney-general, the solicitor-general, and Bacon on legal matters concerning examination reports of two Catholic prisoners. Bacon's first surviving legal works—‘A brief discourse upon the commission of Bridewell’ and another discourse in law French on crown prerogatives and ownership—were also written in this period. (There is however a near contemporary attribution of the former to William Fleetwood, recorder of London, GL, MS 9384.) In August 1588 Bacon was appointed to a government committee examining recusants in prison and a few months later, in December 1588, he was appointed to a committee of lawyers which was to review existing statutes. When a new parliament met in February 1589 he was busy throughout the session with committee work. In November 1589 he was granted a reversion of the clerkship of star chamber. Although he did not succeed to the post until 1608 the reversion demonstrated Bacon's growing importance and, since the post was worth £1600 per annum, it gave him a promise of economic security.

This steady advancement of Bacon's political and legal career is aptly reflected by the importance attached to a position paper he wrote on ecclesiastical politics. ‘An advertisement touching the controversies of the Church of England’ (written some time between 1589 and 1591) was Bacon's response to the conflict between the Church of England and the nonconformists, sparked off by the publication of the pamphlets said to be written by one Martin Marprelate. These tracts used scathing satire in heavily censuring the Church of England. Richard Bancroft, chaplain to Sir Christopher Hatton and a future bishop of London, hired such writers as John Lyly and Thomas Nashe to answer in a similar irreverent style.

Avoiding the mutual muckraking of both sides in the controversy Bacon emphasized his impartiality and called for a cessation to hostilities. According to him the puritans too easily imitated the government of foreign presbyterian churches. ‘It may be’, Bacon wrote in a remarkable passage, that ‘in civil states, a republic is a better policy than a kingdom’. Yet, in church government, hierarchy rather than ‘the parity and equality of ministers’ was to be sought (Bacon, ed. Vickers, 10). Nevertheless Bacon placed the main blame for the controversy at the bishops' door. ‘The imperfections ... of those which have chief place in the church have ever been principal causes and motives of schisms and divisions’ (ibid., 6). Although his name was not mentioned in the tract Bancroft received Bacon's bitterest censure.

‘An advertisement’ was never printed in Bacon's lifetime, but several extant manuscript copies attest to its wide circulation. Both sides of the controversy—a presbyterian tract in 1591 and a treatise by Bancroft in 1593—invoked ‘An advertisement’ in their own defence (Bacon, ed. Vickers, 498). Bacon's famous comment on another occasion that ‘her Majesty, not liking to make windows into men's hearts and secret thoughts’, also indicates his middle path (Works, 8.98).

In 1592 Bacon was commissioned to write a response to the Jesuit Robert Persons's anti-government tract Responsio ad edictum reginae Angliae, entitled ‘Certain observations made upon a libel’. Just like Thomas Wilson and Thomas Norton in 1570, so Bacon in 1592 emphasized ‘the resemblance between the two Philips, of Macedon and Spain’, and thus identified England with republican Athens. English statesmen and counsellors were just like ‘the Orators’ in Athens, being ‘sharpest sighted’ and looking ‘deepest into the projects and spreading’ of the two Philips (Works, 8.182–3).

Bacon and Essex

Bacon's life and career during the 1590s was dominated by his close friendship with Robert Devereux, the second earl of Essex. It is not clear when this relationship began and when it developed into an intimate friendship, but as early as summer 1588 there was at least a patronage relationship. In June 1588 Bacon wrote to the earl of Leicester asking his support for a suit which Essex was advancing on Bacon's behalf.

Quite suddenly in the early 1590s Bacon broached the entirely novel theme of natural philosophy that occupied him for the rest of his life. Early in 1592 he wrote to Lord Burghley. In one of his most famous letters, assuring his ‘devotion’ both as ‘a good patriot’ and ‘an unworthy kinsman’, Bacon expressed anxiety about his age: ‘I wax now somewhat ancient; one and thirty years is a great deal of sand in the hour-glass’. But instead of merely putting forward a suit for office, he was, Bacon told his uncle, pursuing a place for a higher purpose. He wrote:

I confess that I have as vast contemplative ends, as I have moderate civil ends; for I have taken all knowledge to be my province; and if I could purge it of two sorts of rovers, whereof the one with frivolous disputations, confutations, and verbosities, the other with blind experiments and auricular traditions and impostures, hath committed so many spoils, I hope I should bring in industrious observations, grounded conclusions, and profitable inventions and discoveries; the best state of that province. This, whether it be curiosity, or vain glory, or nature, or (if one take it favourably) philanthropia, is so fixed in my mind as it cannot be removed. And I do easily see, that place of any reasonable countenance doth bring commandment of more wits than of a man's own; which is the thing I greatly affect. (Works, 8.109)

In 1592 Bacon also produced a device entitled ‘Of tribute, or, Giving that which is due’. There is no evidence that it was ever performed. The device consists of four speeches—the first arguing for ‘the worthiest virtue’ (fortitude), the second for ‘the worthiest affection’ (love), the third for ‘the worthiest power’ (knowledge), and the fourth for ‘the worthiest person’ (Queen Elizabeth). The one on knowledge enlarged on the plans and ambitions which Bacon outlined in his letter to Burghley. He excoriated extant natural philosophy for both its barren products and its futile methods, the main culprits being ‘the Grecians’ (scholasticism) and ‘the alchemists’ (Paracelsians). Bacon thus argued against the barrenness of scholastic natural philosophy and against the preposterous claims of alchemy. He hinted that he would form a new method which would replace both exploded schools, and produce not just words but works.

‘Is truth ever barren?’, Bacon asked and immediately provided the answer in another rhetorical question: ‘Shall he not be able thereby to produce worthy effects, and to endow the life of man with infinite new commodities?’ Moreover, he pointed to the mechanical artificers who had created printing, artillery, and the compass, as his forerunners. It is extremely significant that Bacon called knowledge ‘the worthiest power’, thus making as early as 1592 his novel link between natural philosophy and power (Bacon, ed. Vickers, 34–6).

When a new parliament met on 19 February 1593 Bacon sat as knight of the shire for Middlesex. This mirrored his enhanced importance. Nevertheless it was a catastrophic session for him. The queen had had two reasons to summon parliament: religious conformity and money. When the appeal for funds was made Bacon was among the first to speak, but curiously pleaded ignorance of war and did not speak about money but about the urgent need of a law reform. The appointed committee suggested the repetition of the exceptional grant of two subsidies made in the previous parliament. But in a conference of both houses Lord Burghley announced that the Lords would not assent to anything less than three subsidies, paid in three years (twice as quickly as usually), and that the assessments must be improved.

Burghley's son, Sir Robert Cecil, reported this message to the House of Commons. With Cecil seated Bacon, who had been a member of the committee of both houses, rose and, while assenting to three subsidies, opposed joining with the Lords in granting it. The Commons, Bacon insisted, should stand upon its privilege of first offering a subsidy. If his earlier speech had been rather irrelevant this one must have been a worse irritant for his uncle. But more was to come. After several days of work the Commons referred the matter to yet another committee. The councillors wanted three subsidies paid in three or four years. When the committee met again, on the morning of 8 March, Bacon rose and announced that he would assent to three subsidies ‘but not to the payment under six years’. ‘The gentlemen’, he said, ‘must sell their plate and the farmers their brass pots ere this will be paid. And as for us, we are here to search the wounds of the realm and not to skin them over’. He was convinced that a quick payment of three subsidies in three years would ‘breed discontentment in the people’ and make ‘an ill precedent’. Moreover, history amply demonstrated that ‘of all nations the English care not to be subject, base, taxable’ (Works, 8.223). Bacon's heroic eloquence seems to have won no support. Walter Ralegh argued against him, as did Cecil, who refuted each of his cousin's arguments. The committee agreed to three subsidies payable in four years.

Many of those who had opposed the unprecedented demand for three subsidies in three years incurred the ire of the queen. Bacon's speeches, while ostensibly high principled, were scarcely prudent for a gentleman looking for a career in the service of the queen. He may have been reprimanded during the session, and certainly felt the queen's anger afterwards. The queen thought that Bacon was ‘in more fault than any of the rest in Parliament’ (Works, 8.254). As soon as Burghley had informed him of the queen's anger Bacon tried to excuse his speech. ‘The manner of my speech’, he told his uncle, ‘did most evidently show that I spake simply and only to satisfy my conscience, and not with any advantage or policy to sway the cause’. In expressing his sincere opinions Bacon had simply endeavoured to signify his ‘duty and zeal towards her Majesty and her service’ (ibid., 8.234). ‘There is’, he later added, ‘variety allowed in counsel, as a discord in music, to make it more perfect’ (ibid., 8.362).

Such justifications failed to make amends. The disaster of Bacon's speeches was made much worse by the fact that immediately afterwards Essex launched a campaign on Bacon's behalf for the office of attorney-general. During the campaign Bacon gained some legal experience. In January and February 1594 he argued his first two cases in king's bench and one in the court of exchequer, which won him general applause. He was also involved in the treason trial of Roderigo Lopez, and prepared its official account. Yet by spring 1594 it was clear that Edward Coke was to become the next attorney-general. Bacon told Essex that he would ‘retire myself with a couple of men to Cambridge, and there spend my life in my studies and contemplations, without looking back’ (Works, 8.291).

No such retirement took place. In July 1594 the queen made Bacon one of her learned counsel and he was employed in several legal cases. One of them—obviously an investigation of the aftermath of Dr Lopez's conspiracy—required him to travel north. Due to an illness Bacon got no further than Huntingdon. He took this opportunity to visit Cambridge and take his MA degree.

Bacon wrote parts of the Gesta Grayorum, the Christmas festivities of 1594–5 at Gray's Inn. It was presented on 3 January 1595 in front of a formidable audience. Similar to the earlier device (‘Of tribute’), it had six speakers arguing their choice of life. The first defended ‘the Exercise of war’, the second advised ‘the Study of Philosophy’, the third ‘Eternizement and Fame by Buildings and Foundations’, the fourth defended ‘Absoluteness of State and Treasure’, the fifth ‘Virtue and a gracious Government’, and the sixth ‘Pastimes and Sports’. The second speech, pleading the cause of philosophy, urged ‘the conquest of the works of nature’, commending the erection of ‘a most perfect and general library’, ‘a spacious, wonderful garden’, ‘a goodly huge cabinet’, as well as ‘a still-house [laboratory], so furnished with mills, instruments, furnaces, and vessels, as may be a palace fit for a philosopher's stone’ (Bacon, ed. Vickers, 54–5). But the device was part of Christmas festivities, and the day was carried by the last counsellor who declared ‘let other men's lives be as pilgrimages ... but princes' lives are as progresses, dedicated only to variety and solace’ (ibid., 60).

When Edward Coke was appointed attorney-general the solicitor-generalship became vacant. Essex pressed hard to secure it for Bacon, and if anything the suit became even more prolonged and exhaustive than the earlier one. Bacon even asked for a licence to travel abroad but the queen refused him. Venting his frustration to his brother Anthony, Bacon said that the queen had sworn that ‘she will seek all England for a Solicitor rather than take me’ (Works, 8.348). By July 1595 he could no longer contain himself but wrote to Lord Keeper Puckering: ‘There hath nothing happened to me in the course of my business more contrary to my expectation, than your Lordship's failing me and crossing me now in the conclusion, when friends are best tried’ (ibid., 8.364–5). Trying to atone Essex referred to Bacon's burst of anger as ‘a natural freedom and plainness’, which Bacon had also used with Essex as well as with other friends (ibid., 8.366).

Whatever Bacon's hopes, they were dashed early in November 1595 when the queen appointed Sir Thomas Fleming as solicitor-general. Most scholars agree that Bacon's opposition to the subsidy bill in 1593, which had offended the queen, and Essex's perseverance in pursuing the suit, which had annoyed her, account for Bacon's failure to obtain the post. Essex consoled Bacon by offering him a gift of land. Bacon responded that while he was ‘more beholding to you than to any man’, yet Essex could not purchase his loyalty, and that his first obligation was always to the queen and the public service (Works, 8.373). Afterwards, Bacon sold the land for £1800.

The painful experience of these suits led Bacon temporarily to entertain the idea of a purely scholarly career and ‘not to follow the practice of the law ... because it drinketh too much time, which I have dedicated to better purposes’ (Works, 8.372). But when, in spring 1596, the office of master of the rolls fell vacant it gave him new hope that a place would also be vacated to which he could succeed, receiving strong support from Essex.

Intellectual and literary pursuits, most of them closely related to Essex and his circle, took up much of Bacon's time in the late 1590s. Essex had commissioned him to write a device for the Accession day celebration, presented at Essex House on 17 November 1595. Again Bacon's contribution consisted of three men defending their respective forms of life: a hermit defending contemplation, a soldier defending fame, and a statesman arguing for experience. These arguments were refuted by a squire who concluded by confirming his master's (representing Essex) dedication to the queen. In this, as in the earlier dramatic entertainments, Bacon could be seen as dramatizing his own choices between the active and contemplative modes of life.

In addition to literary devices Bacon used letters of advice to display his learning and intellectual abilities, and to put his ideas across. The first of these was a series of three letters addressed to the earl of Rutland (who travelled in Europe during 1595–7) perhaps late in 1595 or early in 1596, which Bacon wrote on Essex's behalf. Bacon strongly argued for the vita activa, which needed above all ‘liberality or magnificence, and fortitude or magnanimity’. Underlying these virtues, however, was ‘knowledge, which is not only the excellentest thing in man, but the very excellency of man’. Restricting his account to ‘civil knowledge’, Bacon emphasized that such a knowledge consisted of doing ‘good unto others’ and it therefore contrasted sharply with ‘the study of artes luxuriae’ (Works, 8.9–12).

Bacon wrote a somewhat different letter of advice to Essex himself in October 1596, after the latter's Cadiz expedition had weakened his position at court. Calling Essex ‘a nature not to be ruled’, Bacon advised him studiously to avoid giving such an impression. But he also counselled him to shun the impressions of ‘a military dependence’ and ‘a popular reputation’. In both these, however, the earl should avoid the appearance but not the characteristic itself. He must abolish a military dependence ‘in shows to the Queen’ but retain it in practice. Similarly, in the queen's presence he must ‘speak against popularity and popular courses vehemently; and tax it in all others: but nevertheless to go on in your honourable commonwealth courses as you do’ (Works, 9.41–4).

Yet another intellectual pursuit to which Bacon devoted time in the 1590s was his idea of reforming the English law. In 1593 he had mentioned in parliament how in ancient Rome ‘ten men’ had been appointed ‘to correct and recall all former laws’ (Works, 8.214). In the Christmas festivities at Gray's Inn in 1594–5 he had the counsellor advising the prince in ‘Virtue and a gracious Government’ to advocate a similar project (Bacon, ed. Vickers, 59). In new year 1597 Bacon presented the queen with a work, ‘Maxims of the law’, which was meant as an example of how the English law should be restructured. It consists of twenty-five maxims in Latin each of which is followed by a fuller treatment.

Early in 1597 Bacon appeared in print for the first time. Some of his essays had already been circulated in manuscript (in 1597 he noted that ‘they passed long agoe from my pen’; Works, 6.523), and in 1596 one of them was plagiarized in Edward Monings's The Langrave of Hessen his Princelie Receiving of her Majesties Embassador, which borrowed a few passages from Bacon's essay ‘Of studies’. On 24 January 1597 one Richard Serger entered in the Stationers' register ‘a book entitled ESSAYES of M.F.B. with prayers of his Sovereigne’ (Bacon, ed. Vickers, 546). In order to forestall this publication Bacon immediately assigned the rights to Humfrey Hooper. On 7 February 1597 the first edition of Bacon's Essayes, together with Religious Meditations and Places of Perswasion and Disswasion, was published. The ten essays treated personal and courtly issues and belong, too, to the literature of advice. They were written in a terse, aphoristic style (individual sentences were marked with a paragraph sign), which Bacon conceived as a genre setting down discrete observations on life, and aspiring to some kind of objective validity. The slim volume had considerable success and was reprinted in 1597, 1598, 1606, and 1612.

In 1597 Bacon tried his fortune with Lady Hatton, a young, rich widow (and the daughter of Burghley's eldest son)—but without success. To make matters worse she married Bacon's old rival Edward Coke in November 1598. One of the chief reasons for Bacon's suit was economic. His estate was ‘weak and indebted’, both because of the lack of inheritance and because he in his ‘own industry’ had ‘rather referred and aspired to virtue than to gain’ (Works, 9.61). When the marriage suit failed Bacon endeavoured to use his reversion of the star chamber clerkship to relieve his necessities. He would give it to the lord keeper Thomas Egerton's son if Egerton would give him the mastership of the rolls. Again the plan fell through, and in September 1598 Bacon was arrested for debt. Although his income increased considerably over time his economic situation was never secure, and he often had difficulties in settling his debts.

In the parliament which sat from October 1597 to February 1598 Bacon was an active member for Ipswich, serving in numerous committees. He delivered his speech in favour of three subsidies, payable in three years. He initiated the important social and economic legislative work of the session with a motion against enclosures and the depopulation of towns and houses of husbandry, and for the maintenance of tillage, which he had not written, he said, ‘with polished