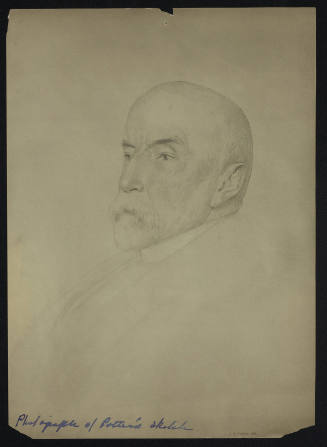

Henry Adams

Adams, Henry (16 Feb. 1838-27 Mar. 1918), historian, novelist, and critic, was born Henry Brooks Adams in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Charles Francis Adams, a diplomat, legislator, and writer, and Abigail Brooks. He enjoyed unparalleled advantages, chief among them his famous name and many family connections: he was the great-grandson of President John Adams and the grandson of President John Quincy Adams. Henry's father was a powerful force in national and international politics, serving as a congressman, a vice presidential candidate in 1848, and his country's minister to Great Britain during the American Civil War. He was also frequently mentioned as a possible presidential candidate. Presidents, high-ranking diplomats, and world leaders were thus as familiar to Adams as aunts, uncles, and grandparents are to less-favored youth.

Although Adams later depreciated his formal education, he attended the country's best schools, including the Dixwell School, and he graduated from Harvard College in 1858. Following Harvard he spent two years in Europe on what was then called "the grand tour." During this tour he became a newspaper correspondent for the first time. His letters to the Boston Courier in the spring of 1860 included an interview with Italian revolutionary leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, a meeting that Adams was able to arrange through family connections.

Adams returned to the United States in the fall of 1860, in time to vote for Abraham Lincoln for president. He also began reading law in Boston but ceased his legal studies almost immediately when the newly elected Lincoln appointed his father as minister to Great Britain. When his father asked Adams to accompany him as a private secretary he accepted, no doubt relieved since he had little desire to study or practice law. During the time that he spent in England Adams added greatly to his list of acquaintances and friends, including international celebrities. Besides being presented at court to Queen Victoria, the young Adams met political luminaries such as Prime Minister Henry Palmerston, reformers John Bright and Richard Cobden, and political philosopher John Stuart Mill. His social world extended to literary giants such as Robert Browning and Charles Dickens and to Britain's foremost geologist, Sir Charles Lyell, who had recently embraced Charles Darwin's controversial theory of evolution. Indeed, Adams reviewed the tenth edition of Lyell's Principles of Geology (1867) for the North American Review. In this piece, as well as in numerous letters and published writings over the years, Adams expressed serious doubts about evolution, not because of any theological misgivings (Adams was an agnostic by this time) but because of a strong streak of personal pessimism that led him to doubt any sort of progressive theory, especially when it involved human society. It was also during the years in England that Adams made a lifelong friend in Charles Milnes Gaskell who, like his father, James Milnes Gaskell, moved in liberal circles and was well connected socially. Throughout the rest of their lives Adams and Gaskell shared a deep interest in political reform in their respective countries and conducted a fascinating transatlantic correspondence.

While in England Adams began to give a great deal of thought to what had brought the United States into a ruinous civil war and to what he and other well-placed young men of his generation might do to save the American political experiment that his own ancestors had helped launch less than a century before. His reading of Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America (1835-1840) and several works by Mill convinced him that he and his counterparts back home could indeed play an important part in salvaging the United States. Particularly helpful in drawing such a conclusion was Mill's Consideration on Representative Government (1861), in which the author concluded that the masses need to be guided by a moral and intelligent elite.

In order to help guide public opinion in the United States after his return from England in 1868, Adams settled in Washington, D.C., as a freelance journalist, contributing articles to the North American Review, the Nation, and various British periodicals. Adams's most bitter attacks were aimed at President Ulysses S. Grant and at various individuals connected with the corrupt Grant administration.

In 1870, after much pressure from his family, Adams accepted a teaching position at Harvard, along with the unpaid editorship of the North American Review. He began teaching courses in medieval history but soon went on to develop offerings in early U.S. history. In 1872 Adams married Marian "Clover" Hooper (Marian Hooper Adams); they had no children. Meanwhile, Adams became active in reform politics, joining the Liberal Republicans in 1872 in their unsuccessful attempt to deny Grant a second term. During the Harvard years he also continued to write a number of articles for the periodical press. Adams resigned his editorship of the North American Review in 1876 and his Harvard position in 1877, in part because he felt smothered by such close proximity to his family and to Boston's stiff social conventions. He also left teaching in order to concentrate his energies on researching and writing the history of the United States during the early nineteenth century--the time, he had concluded, that the American experiment had begun to unravel.

Upon leaving Harvard Adams settled in Washington, the city that he had come to prefer more than any other in the country and a place where he could make use of government archives for his ambitious historical research. He and his wife also took several trips to Europe, in part so that he could search foreign archives for material relating to American history. The principal result of these labors was his nine-volume work The History of the United States during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (1889-1891). Throughout the work there is a note of fatalism and pessimism: the United States had failed to realize its highest ideals because the American people could not escape the bonds of human nature, and the rest of the world refused to allow the nation to pursue its noblest goals without interference. According to Adams, countries as well as their leaders--the United States included--"were bourne away by the stream, struggling, gesticulating, praying, murdering, robbing; each blind to everything but a selfish interest, and all helping more or less unconsciously to reach the new level which society was obliged to seek" (vol. 4, p. 302).

In the course of writing his history, Adams managed to publish biographies of Albert Gallatin (1879) and John Randolph (1882), both important political personalities of the Thomas Jefferson and James Madison periods and both, according to Adams, brought down by forces over which they had little or no control. Adams thus finished his studies of early nineteenth-century U.S. history by concluding that his countrymen were not, as many of them seemed to believe, a chosen people under a new dispensation and thereby released from the common failings of humanity.

The years of writing history in Washington were the happiest in Adams's adult life, despite the fact that his marriage was childless. Residing across the street from the White House on Lafayette Square, the Adamses constantly entertained people of merit, distinction, and wit. Among their closest friends were diplomat and writer John Hay and naturalist Clarence King. King, Hay and his wife, Clara, and the Adamses formed an intimate circle that they dubbed the "Five of Hearts." Out of this social scene, and out of a continuing fascination with American politics, came much of the material for Adams's anonymously written novel, Democracy (1880), a thinly veiled account of political corruption and intrigue in the nation's capital.

Adams published a second novel, Esther, in 1884 (under the pseudonym Frances Snow Compton); the book grappled with the seemingly irreconcilable conflict between science and religion that troubled many well-educated men and women during the Gilded Age. Its protagonist, Esther Dudley, is forced by her lack of faith to break off her engagement to a young clergyman and is nearly driven to suicide at the end of the novel.

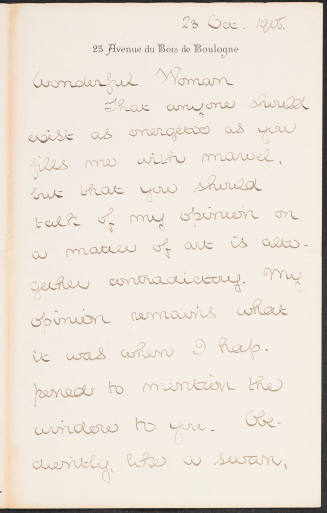

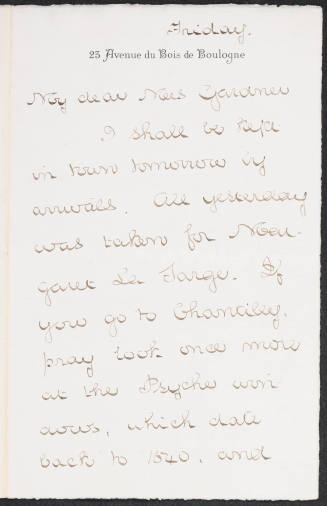

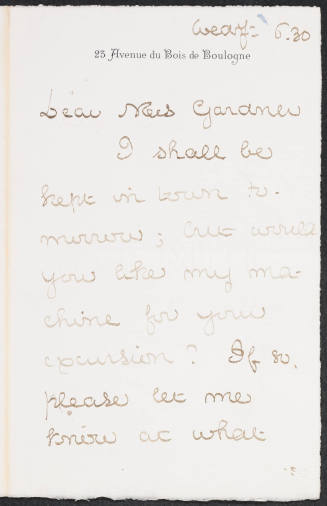

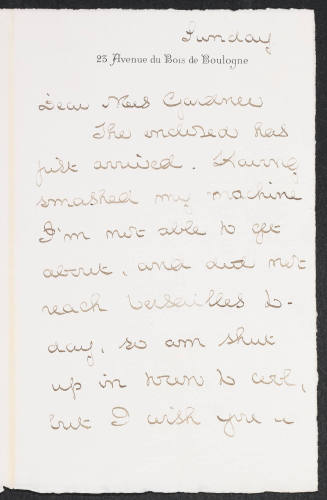

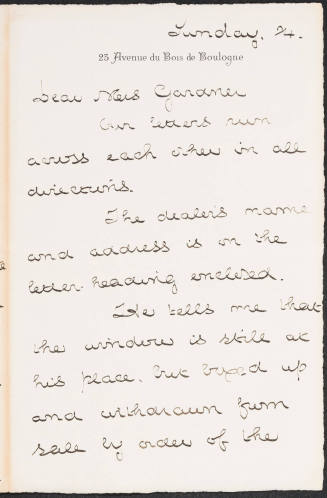

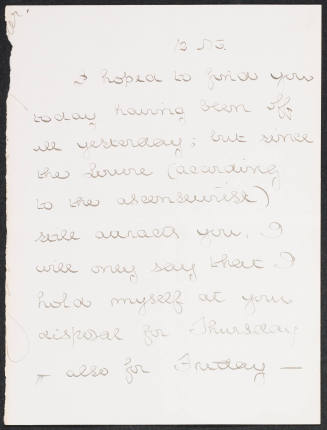

Many observers have connected the character and dilemmas of Esther Dudley with Adams's wife, Marian, who likewise lacked religious faith and who, unlike Esther, actually took her own life in 1885 after a period of deep depression. Marian's suicide was a terrible blow to Adams, one from which he never fully recovered. He sought distraction in an around-the-world voyage (1890-1892) with artist and friend John La Farge. His friendship with Elizabeth Sherman Cameron, the wife of U.S. senator Don Cameron from Pennsylvania, also became an important source of comfort after the suicide. This friendship--which soon turned to love, at least on Adams's part--has been the subject of intense speculation over the years, although it seems that the relationship was emotional rather than physical.

Adams interrupted his ambitious journey with La Farge with a long stay in Paris. This marked the beginning of an annual trek to France (until World War I put a halt to the peregrinations), with Adams typically spending the summer and autumn months in the French capital and the rest of the year in Washington. Using Paris as a base, he took frequent trips around France as well as to other parts of Europe, including a visit to Russia in 1901. Adams could easily afford such travel with an income, on various inheritances, of about $60,000 per year by 1900.

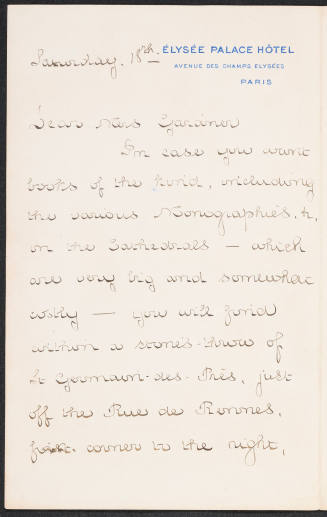

It was during the 1890s in France that Adams renewed his interest in French Gothic cathedrals. Out of this fascination came his book Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres, privately printed in 1905 and published in 1913. Although styled as an elaborate guidebook to two of France's most magnificent works of architecture, the book is a hymn of praise for the High Middle Ages, increasingly a golden age in the past for Adams and for many other thinkers on both sides of the Atlantic who were alarmed at various trends in the "modern world." Chief among these trends was the lack of intellectual and spiritual unity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the denial by many scientists and philosophers of either absolute truth or universal law.

This contrast between what Adams called the unity of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (as symbolized by the Virgin of Chartres) and the multiplicity of the early twentieth century (as symbolized by the dynamo) was a recurrent theme in The Education of Henry Adams, privately issued in 1904 and 1906 and published in 1918. Although autobiographical in nature, Adams refers to himself in the third person and ignores many important aspects of his life, including the years of his marriage and his wife's tragic suicide. The book also conveys a strong message of personal failure that was at odds with the reality of his successful life. This persona of failure has been interpreted by readers in various ways: as a manifestation of Adams's pessimism, as evidence of his disappointment over his role in American politics, or simply as a vehicle for reflecting on the shortcomings of the modern world as a whole and American life in particular.

The Education of Henry Adams, however fascinating, must be approached with much care because of Adams's many calculated distortions. It should be read along with other writings by Adams and especially in the context of his sparkling and often brilliant personal correspondence, most of which has been collected and published. Yet even there, the tone of personal and social criticism is unmistakable. Adams's social critiques also appeared in several works that were published during his last decade, including two essays intended for historians, "The Rule of Phase Applied to History" (1909) and "A Letter to American Teachers of History" (1910). Both of these works were attempts to draw analogies between recent theories in physics, such as the "rule of phase" and the second law of thermodynamics, and social and political trends in what Adams continued to insist was an imperiled modern world. Adams saw such theories, in part, as a means of combating assertions by social evolutionists (or social Darwinists as they are often called) that progress was automatic and inexorable.

Despite his mordant views and lingering grief over his wife's death, Adams continued to enjoy a wide circle of friends during the last period of his life. Hay, who was the secretary of state from 1898 to 1905, remained a close friend and confidant until his death in 1905. Hay and Adams had built adjoining houses on Lafayette Square in Washington during the mid-1880s that were designed by their architect friend Henry Hobson Richardson. Adams and Hay often took walks in the afternoon, with Hay unburdening himself to Adams. Although Adams seldom hesitated to give advice, it remains unclear whether he had any direct influence on foreign policy. Yet he often served as an unofficial go-between, meeting with foreign envoys in his home and conveying their conversations to Hay.

In this way Adams continued to enjoy an insider's view of U.S. foreign policy. At the same time, he used his yearly stints in Paris as a window onto the European scene. He was particularly alarmed by the race for colonial spoils at the beginning of the twentieth century, and he was highly critical of his own country's decision in 1898 to annex the Philippines at the end of the Spanish-American War. Nevertheless, he grew alarmed at early signs of decline in British power, fearing that a decay of the British Empire would lead to disequilibrium and possibly war. "To anyone who has studied history," he wrote to Hay in 1900, "it is obvious that the fall of England would be paralleled by only two great convulsions in human record: the fall of the Roman Empire in the fourth century and the fall of the Roman Church in the sixteenth." Another recipe for disaster was the great potential of Russia, coupled with tremendous political and social instability in that country. As he confessed to his friend Elizabeth Cameron in 1904, "I am half crazy with fear that Russia is sailing straight into another French Revolution which may upset all Europe and us too." The outbreak of World War I in 1914 confirmed Adams's worst fears, but he was consoled by the hope that the war might lead to a great Atlantic alliance that would keep the peace for many years.

Adams's health deteriorated after he suffered a serious stroke in 1912, although he recovered enough to go about most aspects of his daily life. He died at his home in Washington, D.C. Adams was buried in Washington's Rock Creek Cemetery, beside his wife and beneath the large bronze statue of a grieving woman that Adams had commissioned from his sculptor friend Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the years just after Marian's death.

Although Adams's reputation has passed through several phases since his death, his analyses of American society and politics and his insightful criticisms of modern Western culture assures his continued relevance and importance. Adams was also a gifted writer whose prose style and use of symbolism mark him as one of the country's greatest literary figures.

Bibliography

Adams's papers have been assembled in various places, but the most important repository is the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston. These papers are part of that institution's impressive collection relating to the larger Adams family. The bulk of Adams's correspondence is in J. C. Levenson et al., eds., The Letters of Henry Adams (6 vols., 1983; rev. ed., 1988). The most complete biography of Adams remains the three-volume work by Ernest Samuels, The Young Henry Adams (1948), Henry Adams: The Middle Years (1958), and Henry Adams: The Major Phase (1964). A one-volume condensation of this trilogy, including new materials that had come to light since the earlier publications, is Samuels, Henry Adams (1989). Also see Edward Chalfant, Both Sides of the Ocean: His First Life, 1838-1862 (1982), and Chalfant, Better in Darkness, 1862-1891 (1994). Among the many books on various aspects of Adams's life and works are David R. Contosta, Henry Adams and the American Experiment (1980); William Dusenberre, Henry Adams and the Myth of Failure (1980); Levenson, The Mind and Art of Henry Adams (1957); and Brooks D. Simpson, The Political Education of Henry Adams (1996). A volume of essays by leading Adams scholars is Contosta and Robert Muccigrosso, eds., Henry Adams and His World (1993). Studies of Adams's family life include Earl N. Harbert, The Force So Much Closer Home: Henry Adams and the Adams Family (1977); Otto Friedrich, Clover (1979); and Eugenia Kaledin, The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams (1981). Concerning Adams's many friends see Patricia O'Toole, The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends (1990), and Ernest Scheyer, Circle of Henry Adams (1970). Also very helpful in understanding Adams and his rich social connections is Harold Dean Cater's lengthy introduction to his collected Adams letters, Henry Adams and His Friends (1947). An exploration of the relationship between Adams and Elizabeth Cameron may be found in Arline B. Tehan, Henry Adams in Love (1983).

David R. Contosta

Source:

David R. Contosta. "Adams, Henry";

http://www.anb.org/articles/14/14-00009.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Jul 22 2013 16:09:10 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)