Charles Dudley Warner

Warner, Charles Dudley (12 Sept. 1829-20 Oct. 1900), author and editor, was born in Plainfield, Massachusetts, the son of Justus Warner and Sylvia Hitchcock, farmers. In 1837, three years after her husband died, Sylvia Warner took her two sons to a guardian in Charlemont, Massachusetts, and, in 1841, on to her brother in Cazenovia, New York. Warner attended classes at the Oneida Conference Seminary in Cazenovia, enrolled at Hamilton College, and graduated in 1851 with a B.A. While still a student he published articles in the Knickerbocker Magazine and was inspired by the favorable reception of his commencement speech to publish The Book of Eloquence: A Collection of Extracts in Prose and Verse, from the Most Eloquent Orators and Poets . . . (1853). After a stint as a railroad surveyor in Missouri in 1853-1854, Warner lived with an uncle in Binghamton, New York, worked as a real-estate conveyancer, and read law. In 1856 he received a bachelor's degree in law from the University of Pennsylvania. That same year Warner married Susan Lee; the couple had no children. He practiced in Chicago from 1858 to 1860.

Disliking his legal work, diminished as a consequence of the panic of 1857, Warner became an associate editor of the Hartford Evening Press, a Republican paper newly established by Joseph Roswell Hawley, whom he had met at the Oneida seminary and who was also a Hamilton alumnus. When the Civil War began, Hawley joined the Union army, whereupon Warner--too nearsighted for military service--was promoted to editor in chief. In 1867 he became part owner and editor of the Hartford Courant, which absorbed the Evening Press. He and his wife spent the following year vacationing in Europe, during which time he sent back popular travel dispatches to the Courant, later gathered into Saunterings (1872). His success as a book author had begun a year earlier with My Summer in a Garden, a set of whimsical essays written in a style often compared to that of Charles Lamb, one of Warner's favorite authors. His garden was his three-acre homestead, later called "Nook Farm," in Hartford. Wide acceptance of My Summer in a Garden was guaranteed when the celebrated Henry Ward Beecher provided a gracious introduction. The Reverend Beecher was the brother of Warner's Hartford neighbor Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin.

In 1873 Warner and his most famous Nook Farm neighbor, Mark Twain, were challenged one evening by their wives to write a better novel than the ones they were noisily ridiculing. The result was Warner and Twain's The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-Day (1874), a sometimes bitter but often jocose satire of political corruption in the East and greedy land speculation in the West. The response of American readers to The Gilded Age was varied. Many found it vicious or merely childish, while others praised the accuracy and bite of its satire. British readers delighted in its depiction of American materialism and venality and were pleased that a pair of Americans had criticized their own country. Although it was a quick, moderate bestseller, scholars later regarded The Gilded Age as satirically on target but ill proportioned, its best part being the first eleven chapters, by Twain, and the romantic plot elements, by Warner, being least effective. With the title, however, Warner helped name his era of American history.

Other Hartford literary neighbors included Horace Bushnell, the religious thinker; Harriet Beecher Stowe's suffragette sister Isabella Beecher Hooker and her lawyer husband John Hooker; J. Hammond Trumbull, the antiquarian; and Joseph Hopkins Twichell, a former Civil War chaplain and an author. Warner knew and was admired by all of them. The Hartford literary community was generally amiable, productive, and influential. William Dean Howells, the editor-novelist, was Warner's most significant contact with literary life outside Connecticut.

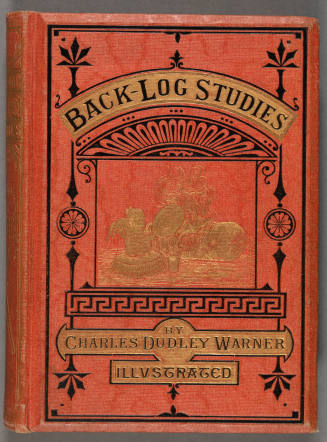

Having achieved a loyal audience, Warner set out to become a popular voice of Victorian America, a culture of wide interests but settled values. In the next quarter of a century, he turned out book after book in several genres, attracted a loyal readership, and earned a comfortable income. My Winter on the Nile: Among the Mummies and Moslems and In the Levant (both 1876) are the best of his several travel books, resulting from four more leisurely trips abroad that he and his wife eventually took. (In all, they lived seven years outside of the United States.) In the Wilderness (1878) was inspired by a vacation in the Adirondacks, and Our Italy, Southern California (1891), by sightseeing on the West Coast. In these and other such books, Warner is detailed, idealistic, mildly witty, and pro-American--but also occasionally a little simple, bland, and bookish. Better is his Being a Boy (1877), an idealization of his childhood in which he recalls working hard on the family farm, enjoying nature when he could, and absorbing old-fashioned, rural moral values. In 1881 he published two biographies. The one on Captain John Smith of Virginia, though thorough, is of little value; but with his Washington Irving, in which he discusses his subject's genial style and praises his moral messages, he inaugurated "The American Men of Letters Series," later volumes of which he edited. Of his several volumes of essays, Backlog Studies (1873) playfully extols rural home life, while The Relation of Literature to Life (1897) soberly theorizes that great books can enlarge the reader's conception of the value of life. The three novels that he wrote on his own form a trilogy of little merit. A Little Journey in the World (1889), The Golden House (1895), and That Fortune (1899) return to the theme of The Gilded Age, warning against the ruthless acquisition of great wealth and its ostentatious misuse and then dramatizing its almost inevitable ruinous consequences. His weakest book, The People for Whom Shakespeare Wrote (1897), is superficial and derivative, and its popularity attests to the loyalty of his readers.

For fifteen years beginning about 1885, Warner took to the lecture circuit not only to promote the cause of the pre-Civil War moral intensity of life but also to espouse such postbellum liberal causes as African-American suffrage, improvements in education, and prison reform. He was a contributing editor of Harper's New Monthly Magazine from 1884 to 1898 and in his eclectic columns prescribed a return to simpler and more agreeable modes of behavior, inveighed against the subjectivity of changing fashions, advocated the development of mechanical and agricultural skills for traditionally disadvantaged laborers, and called for fairer American and international copyright laws. Warner and several friends compiled the Biographical Dictionary and Synopsis of Books Ancient and Modern (1896). Its title does not betray the superficiality of its thousands of brief entries. Dante, for example, is covered in six lines. On the other hand, Library of the World's Best Literature (1896-1897), which Warner assembled with his brother George and others in thirty volumes, justifiably sold far and wide throughout the United States. He earned $10,000 for his part in this enormous publication, which included some introductory material written by him. Warner, whose health deteriorated from about 1898, died in Hartford.

A sincere and generous friend of authors often more talented and forward-looking than he, Warner in his time was a successful and respected advocate of conservative literary trends. He was a little too genteel and confident, given the violent social, cultural, and political changes the progressive writers of the 1890s predicted the twentieth century would bring.

Bibliography

Warner's papers are in more than ninety repositories. The bulk, however, are in the Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.; The Stowe, Beecher, Hooker, Seymour, Day Memorial Library and Historical Foundation, Hartford, Conn.; the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; the Department of Archives and Manuscripts, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge; the Buffalo and Erie County Library, Buffalo, N.Y.; and libraries at Columbia University, Cornell University, Harvard University, Trinity College, Union College, the University of Virginia, and Yale University. Jacob Blanck, Bibliography of American Literature 8 (1990): 477-500, provides a complete Warner bibliography. Mrs. James T. Fields, Charles Dudley Warner (1904), a standard biography, extensively quotes from Warner's travel writings, letters to William Dean Howells, and articles advocating prison reform. Kenneth R. Andrews, Nook Farm: Mark Twain's Hartford Circle (1950), describes the social and intellectual activities of the Hartford literary community of which Warner was a central figure. Justin Kaplan, Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain: A Biography (1966), and John C. Gerber, Mark Twain (1988), analyze The Gilded Age and contrast Twain's and Warner's respective efforts in its composition. Obituaries are in the New York Times, 21 Oct. 1900, and the Hartford Daily Courant, 22 Oct. 1900.

Robert L. Gale

Source:

Robert L. Gale. "Warner, Charles Dudley";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01721.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Jul 22 2013 14:31:26 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)