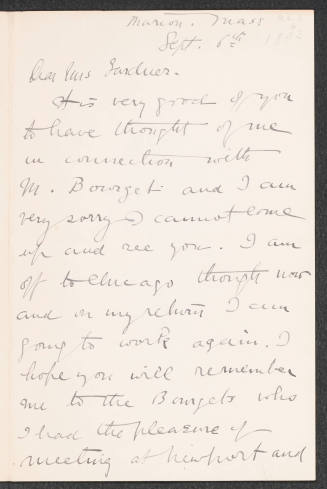

Richard Harding Davis

Newspaperman, war correspondent, novelist.

Richard Harding Davis.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC-USZ62-112723).

Davis, Richard Harding (18 Apr. 1864-11 Apr. 1916), foreign correspondent and author, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the son of Rebecca Harding Davis, a novelist, and Lemuel Clarke Davis, a newspaper editor. Davis's mother, once a promising writer, had turned to churning out potboilers to support her family, and Richard carried from childhood the burden of her frustrated ambitions.

There was no question that he would become a writer. An inattentive student, he drifted through various private academies and was fortunate to be accepted at Lehigh University in 1882. Although his grades placed him near the bottom of his class, he was already a well-developed personality, sporting the foppish wardrobe, complete with fawn-colored kid gloves and cane, that was to become his trademark. His refusal to submit to freshman hazing led to the abolition of the custom at Lehigh and attracted the attention of the national press. In 1885 he made a tour of the southern states as a correspondent for the Philadelphia Inquirer, of which his father was an editor. Invited to withdraw from Lehigh because of poor grades, he studied briefly at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, then became a reporter for the Philadelphia Press.

In 1889 Davis moved on to Charles Dana's New York Sun. During his first full day on the job, he scored a coup, making a citizen's arrest of a notorious con artist who had mistaken him for a gullible tourist. Within a few months Davis turned from the reporter's beat to fiction, launching a series of short stories featuring man-about-town Cortlandt Van Bibber, whose harmless escapades and chivalrous deeds provided the Sun's readers with a glimpse of upper-class manners and mores.

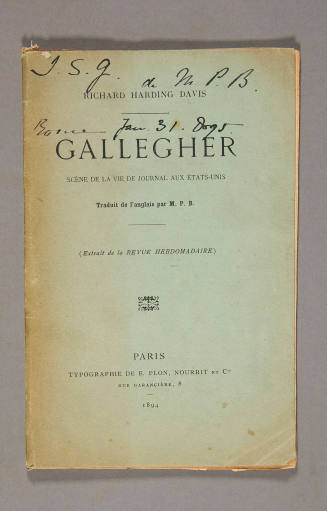

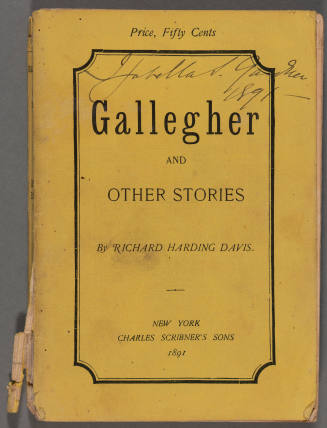

Davis had arrived on the scene at a time when journalism was coming to be seen as an exciting, even glamorous, profession. His novella, Gallegher (1890), the story of a newspaper copy boy who solves a murder, entranced critics and the public alike, inspiring numerous imitations. The popularity of Van Bibber and Gallegher was exceeded only by the celebrity of their creator. Charles Dana Gibson chose Davis as the model for the male counterpart of the Gibson girl, sealing his reputation as the 1890s ideal of American manhood. Pink-cheeked yet rugged, he combined a patina of European sophistication with a moral code that would not have embarrassed a Boy Scout.

A few months after Gallegher's publication, Davis was appointed editor of the prestigious Harper's Weekly. His interest in his editorial duties proved fitful, but he used the post as a platform to establish himself as a foreign correspondent. Vivid description and acerbic, confident judgments were the hallmarks of Davis's reporting from abroad. He never doubted the superiority of Anglo-Saxon virtues, yet he was quick to admit that Anglo-Saxons, like everyone else, often failed to live up to them, criticizing the overseas English for insularity and condescension and Americans for their superficial values and infatuation with overnight success.

Davis's career as a war correspondent began with coverage of an abortive revolution in Honduras in 1893 and continued through the early stages of World War I. In between, he covered almost every international conflict of importance, including the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, the Boer War, and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. He is best remembered for his reporting from Cuba. In 1897 he and artist Frederic Remington visited the island on behalf of the New York Journal, but Davis's attempt to join the Cuban insurgents was frustrated by the Journal's premature publicity. A year later, when the United States declared war on Spain, Davis traveled with the Fifth Army as a representative of the New York Herald and Harper's Weekly.

An admirer of Theodore Roosevelt, Davis attached himself to the Rough Riders, covering (and taking part in) the unit's skirmish with Spanish troops at Las Guasimas. His thrilling, if inaccurate, account of the Rough Riders' charge up Kettle (San Juan) Hill made Roosevelt a war hero. As he and other correspondents on the scene realized, the heroics of the battlefield stood in sharp contrast to the unpreparedness of the general staff. Davis thought it unpatriotic and bad for morale to discuss such matters while victory hung in the balance, but three days after the battle he penned a scathing exposé. The Herald withheld the article until after the signing of the armistice, and when it appeared it created a sensation, in part because such criticisms were not expected from a writer of Davis's relatively conservative views.

In between assignments abroad, Davis enjoyed a second career as an author of short stories and romantic novels. The latter typically featured a self-made American man who engages in deeds of derring-do in an exotic locale and is rescued from cynicism and certain amorphously defined temptations by the love of an intelligent, tomboyish American girl. Soldiers of Fortune (1897) was a tremendous commercial success and established the formula so firmly in the public mind that Davis felt trapped by his own facility. In Captain Macklin (1902) he attempted to move beyond clichés, creating a flawed protagonist and a plot that revealed the American government as capable of deception. He was devastated when reviewers and readers failed to recognize the work as a step forward.

Although Davis was often mentioned in the society pages as the escort of Ethel Barrymore, Maude Adams, heiress Helen Benedict, and others, these relationships were wholly platonic. Throughout his adult life, he suffered periodic bouts of paralyzing depression. Davis's letters contain only scattered hints of the nature of his distress; however, his extreme physical modesty and obsession with personal cleanliness were often noted by his contemporaries. The great love of his youth was the Princess Alix of Hesse, whom he had encountered only once, in passing, when they happened to tour the Acropolis on the same day. This infatuation from afar inspired his novel The Princess Aline (1895), and in 1896 he went to Moscow to report Alix's coronation as the Empress Alexandra of Russia.

Like the protagonist of The Princess Aline, Davis idealized women yet was consumed by anxiety that no particular woman was ideal enough to make him happy. While this conflict presented itself in an extreme form in his personal life, uncertainty about the changing role of women (which he favored, in principle) and shifting moral standards in general, combined with the fear that domesticity meant the end of personal self-development, were themes that struck a responsive chord with his public, both male and female.

In about 1898 Davis concluded that he had at last found the perfect mate in Cecil Clark, the daughter of family friends and an accomplished portrait painter and sportswoman. His decision to ask for her hand in marriage received international publicity when he hired a fourteen-year-old messenger to hand-carry his proposal from London to America in a race against the transatlantic mails. Clark accepted, with the proviso that she would not share her husband's bed. Davis interpreted this condition as an extension of bluestocking high-mindedness and was confident that Cecil would relent in time. They were married in May 1899. She was, however, a lesbian, and the marriage was never consummated.

The acquisition of an elegant if emotionally distant wife and a rural estate in Mount Kisco, New York, spurred Davis to augment his income by writing for the stage. Several of his plays were hits, including The Dictator (1904), a farce that opened on Broadway with John Barrymore as the male lead, and a musical, The Yankee Tourist (1907). But once again, Davis's attempts to tackle more ambitious material were little appreciated by reviewers. One of the highest-paid writers of his day, he was nevertheless perpetually on the brink of bankruptcy, and the fear of commercial failure constrained his efforts at experimentation.

By 1910 Davis had fallen in love with Bessie McCoy, a dancer known as "the Yama-Yama Girl" after her performance of a similarly named novelty number in the Broadway show The Three Twins. Only after the death of his mother, who had remained a dominant influence in his life, did he feel free to ask Cecil for a divorce, and he and Bessie were married in 1912. The summer of 1914 found Davis in Belgium, where he wrote a much-praised account of the Germans' entry into Brussels (With the Allies [1914]) and was briefly detained as a spy. His only child was born the following January--a joyful occasion overshadowed by recurring bouts of angina, misdiagnosed as indigestion. He died of a massive heart attack at "Crossroads Farm," his home near Mount Kisco.

Even at the height of his fame, Davis struck many of his contemporaries as an anachronism. Despite his self-conscious attempt to speak for youth, he remained trapped in an indeterminate sensibility, caught between the modern temperament and the genteel tradition. He was often criticized as a prig and a self-promoter, and for his tendency to write of war as a stimulating exercise for gentlemen. As the critic Philip Littell put it, an ideal day in the life of Richard Harding Davis consisted of "shrapnel, chivalry and sauce mousseline, and so to work the next morning." Davis did his best to live up to his own moral code and generally succeeded. A ferociously hard worker, he often extended himself to help colleagues and friends in need. Moreover, when not carried away by the enthusiasms of the moment, he was a reliable observer. An advocate of a standing army and by temperament pro-establishment, he was skeptical of imperial adventures, and his prejudices were generally subordinated to his sense of fair play.

Much of Davis's journalism and the best of the short stories, especially "The Reporter Who Made Himself King," "The Bar Sinister," and "The Deserter," are still worth reading; even the more dated novels are well paced and radiate with a suppressed eroticism that might profitably be studied by would-be authors of popular fiction. But it is Davis's style that has had a lasting impact on American letters. He made personal journalism an accepted literary genre, and as the prime exemplar of "muscular Christianity" defined a new and self-consciously masculine sensibility. Ernest Hemingway is Davis's most obvious heir, but others, including Frank Norris and Sinclair Lewis, acknowledged a debt to him. One can also discern his influence in the careers of Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe.

Bibliography

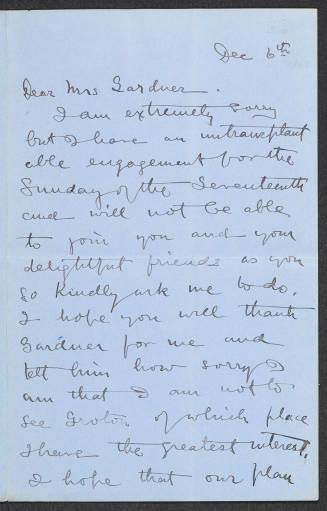

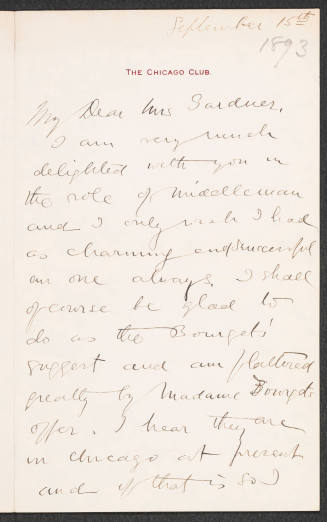

The bulk of Davis's papers are in the Barrett Collection of the Alderman Library at the University of Virginia. Other correspondence remains in the hands of the family and private collectors. Scribner's published an edition of Davis's collected works in 1916, but Henry Cole Quimby, Richard Harding Davis: A Bibliography (1924), lists many additional entries, including unsigned newspaper articles. The Adventures and Letters of Richard Harding Davis (1917), edited by his brother Charles, gives the flavor of Davis's opinions. Fairfax Davis Downey, Richard Harding Davis: His Day (1933), is informal in tone. More complete accounts of his life are in two more recent biographies: Gerald Langford, The Richard Harding Davis Years (1961), and Arthur Lubow, The Reporter Who Would Be King (1992). For a negative view on Davis see Philip Littell, "Richard the Lion-Harding," in Book & Things (1919).

Joyce Milton

Source:

Joyce Milton. "Davis, Richard Harding";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00429.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Jul 29 2013 13:56:43 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)