John Milton Hay

Hay, John Milton (8 Oct. 1838-1 July 1905), diplomat and author, was born in Salem, Indiana, the son of Charles Hay, a physician, and Helen Leonard, a schoolteacher. The family lived in modest circumstances in Salem and then in Warsaw, Illinois. Hay attended Illinois State University (later Concordia College) in Springfield from 1852 to 1855. In 1855 he transferred to Brown University and graduated in 1858 with an M.A., although in fact the degree was more equivalent to a bachelor's degree.

Hay did not find academic life at Brown stimulating but was attracted to the literary circles of Providence and found it difficult to return to the Illinois prairie, where he read law with an uncle in Springfield and was admitted to the bar in 1860. He took a small part in the presidential campaign of Abraham Lincoln and went to Washington as one of Lincoln's personal secretaries. Technically he was a Pension Office clerk. In 1864 he was commissioned as a major and assistant adjutant general in the volunteers. In 1865 he was promoted to colonel, although he never served actively in the military, being deputed to the Executive Mansion. He left Washington in May 1865 following Lincoln's assassination but retained his military commission until 1867. Initially unimpressed with Lincoln, by 1863 Hay had come to consider him the indispensable leader. Lincoln influenced Hay's social and political thought significantly.

Following the Civil War, Hay secured minor diplomatic posts in Europe, serving as secretary of the American legation at Paris (1865-1866), secretary and chargé d'affaires ad interim at Vienna (1867-1868), and secretary at Madrid (1869-1870). He conducted no serious diplomatic work and devoted his time to becoming acquainted with European culture. His democratic beliefs also matured in these years, and he developed a loathing for European autocracy. In Castilian Days (1871) and several poems, Hay praised such romantic democrats as the Spanish Republican Emilio Castelar and even defended the radical Paris Commune.

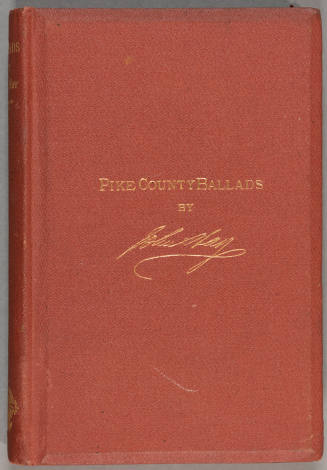

In 1870-1871 Hay achieved fame as a poet, many of his pieces dealing with life on the Mississippi and the frontier. Most appeared in Harper's Weekly. His first collection, Pike County Ballads and Other Pieces (1871), thrust him to national prominence. His writing was often compared with that of Mark Twain, with whom he became a lifelong friend. Several of the poems celebrated political and social democracy.

In 1870 Whitelaw Reid hired Hay as an editorial writer for the New York Tribune, a position he held until 1875. Hay's years in New York served to introduce him to the nation's literary elite.

In 1874 Hay married Clara Louise Stone, daughter of Cleveland investor and railroad magnate Amasa Stone. They had four children. Already economically comfortable from a handsome salary and royalties, Hay gained instant wealth from the marriage. In 1875 he moved to Cleveland. Thereafter, until 1897 when he was appointed American ambassador to Great Britain, Hay held only one official position: from November 1878 to 1881 he was assistant secretary of state, resigning shortly after President James A. Garfield's assassination. He wrote, with John G. Nicolay, his ten-volume History of Lincoln, which was serialized in Century magazine from 1886 to 1890, was first published as a complete set in 1894, and remains important. In addition, he spent his time managing investments, editing the Tribune for six months in 1881 while Reid was away on his honeymoon, working for Republican political candidates, and taking extended trips to Europe, particularly to England.

During these years Hay's social views underwent an important transformation. His pronouncedly democratic, even radical, views receded, and Hay became more and more conservative. The crucial cause was the Great Railway Strike of 1877, which affected Stone's (and Hay's) personal investments. Hay found the strike frightening. In 1883 he responded with an anonymous novel, The Bread-winners: A Social Study, which strongly attacked the labor unions that had struck the railroads. The book, which was widely reviewed, was the first fictional defense of the new industrialism of the Gilded Age, almost a mirror image of such famous reform novels as Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward (1888), Frank Norris's The Octopus (1901), and Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1906). The novel also revealed a certain disdain for uncultivated, nouveaux riches businessmen, but its primary message was that the upper class, whether cultured aristocrats or crass business leaders, should join forces to resist labor leaders and the unwashed masses (particularly Irish immigrants), who challenged those "old-fashioned decencies" (like good manners, hard work, and deference to one's social betters) that Hay increasingly held dear (Hay, Bread-winners, p. 109).

Now Hay identified even more closely with the Republican party; increasingly he saw the Democrats as the source of all evil tendencies in American history. The Bread-winner's villain was Andrew Jackson Offitt, a name indicating Hay's contempt for social and perhaps political democracy. Each election year the Republicans benefited from Hay's purse as well as from his literary talents.

Hay had an extraordinary talent for attracting and keeping friends. "Make all good men your well-wishers," he poeticized, "and then, in the years' steady sifting, / Some of them turn into friends. Friends are / the sunshine of life" (Hay, Complete Poetical Works [1917], p. 185). Hay counted people of many sorts among his friends and acquaintances, including journalists, politicians, and businessmen. He was "much liked by all grades of people in Washington," observed the poet Walt Whitman (Horace Traubel, ed., With Walt Whitman in Camden [1959], vol. 4, p. 43). He thrived on social relationships with literary men and women and cultivated friendships with everyone who was anyone in American literary circles. He was close to Twain, William Dean Howells, Bret Harte, Henry James (1843-1916), and John La Farge (1835-1910), for example.

Hay's closest friends were in a private circle called the Five of Hearts, consisting of John and Clara Hay, Henry B. Adams and Marian "Clover" Adams, and Clarence King. King was a geologist and writer, who led a life of mystery and adventure envied by the more conventional Hay. It was the brilliant and eccentric Henry Adams with whom Hay was closest, despite their disagreements on several issues. When Hay moved to Washington, D.C., in 1886, he and Adams built adjoining houses. After Hay died, Adams made him the hero of his work, The Education of Henry Adams (1918).

Hay also established many friendships with prominent literary people and men of affairs in England. He fell in love with England, with its culture, manners, orderliness, and perhaps also its sharper class distinctions. Hay also believed increasingly in Anglo-Saxon domination as a principle for maintaining peace and order in the world, a view shared by many of his British friends.

Hay's familiarity with England gave rise to rumors by the late 1880s that President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901) would name him ambassador to the Court of St. James's. Harrison demurred, and Hay had to await the election of William McKinley in 1896. There is no question that Hay wanted the appointment. He contributed substantial funds to the McKinley campaign and also to a fund to help McKinley pay some private debts. During the campaign he visited the candidate in Canton, Ohio, and also contributed a campaign speech, "The Platform of Anarchy," which in highly colored language compared the Democratic and Populist candidate William Jennings Bryan and his supporters to "burglars and incendiaries." He then helped McKinley move Reid out of the running for the ambassadorship (a particularly difficult assignment that tested the very limits of Hay's ability to remain friends with Reid) and was elated when, in February 1897, McKinley asked him to go to London.

The nearly seventeen months that Hay spent in London were the happiest of his life. His reputation as a man of letters and his many British friendships gave him immediate entrée into the highest British circles. More fundamental to his diplomatic successes, Hay arrived in London at a time when the British government had decided to forge closer ties with the United States. Hay, a thoroughgoing Anglophile, wanted nothing more than to reciprocate. He was a key player in bringing about the "great rapprochement" that paved the way for the generally close ties between the two countries in the twentieth century. Henry Adams caught Hay's contribution perfectly. "In the long list of famous American Ministers in London," he wrote, "none could have given the work quite the completeness, the harmony, the perfect ease of Hay" (Adams, The Education of Henry Adams, p. 363).

At first, however, much to Hay's irritation, he was not entrusted to conduct negotiations on important matters. Instead McKinley dispatched former secretary of state John W. Foster to handle discussions about a long-standing and dangerous dispute between the United States and Canada over hunting seals in the Bering Sea, while Colorado senator Edward O. Wolcott (because his state's interest in the silver question) represented the United States in currency negotiations. Furthermore, as a sop to Reid, the president asked the editor to represent him at Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. Hay acknowledged Wolcott's competence but feared that Foster would behave tactlessly and botch the negotiations over the seals. In the end an agreement was not reached until 1911, and Hay blamed Foster's bad manners as well as a contentious American press determined to attack England at every opportunity.

If at first Hay had to make way for special representatives, caring for Anglo-American relations during the Spanish-American War of 1898 fell entirely to him. His views about a possible war with Spain are obscure. He was not among those urging a bellicose policy on McKinley, and he admired the president's courage in standing against the storm of popular opinion that demanded war. Even after the Maine was destroyed, Hay exhibited no sense of urgency. Vacationing in Egypt at the time, the ambassador did not cut short his holiday, causing some to complain. Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), for example, wrote privately that he could not "understand how John Hay was willing to be away from England at this time" (Elting Morison, ed., Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, vol. 1 [1951], p. 797).

On the other hand, Hay did not oppose war and sent the State Department many reports from British newspapers that detailed horrendous conditions in Cuba. Many Britons called for American intervention to restore order and even to annex the island. Most important of all, Hay saw that a war with Spain had the potential to improve Anglo-American relations significantly. Once war was declared he used his skills to encourage subtle British support for the United States; among other instances, the British allowed Filipino resistance leader Emilio Aguinaldo to return from Hong Kong to the Philippines to fight the Spanish. In his arguments, Hay emphasized the advantages of a world ruled by Anglo-Saxon benevolence.

With the Spanish-American War in progress and the United States on the verge of a greatly expanded international role, McKinley needed a knowledgeable and experienced person to replace the aging and reputedly senile John Sherman (1823-1900) as secretary of state. In August 1898 he turned to Hay. The prospects of leaving England depressed Hay, and he considered declining the offer. In the end his sense of duty won out, but he was not happy. "All the fun of my life ended on the platform at Euston," he wrote to his wife shortly after his return (Dennett, John Hay, p. 196).

By the time Hay arrived in Washington, the "splendid little war," as Hay put it in one of his most remembered expressions, was over, but peace negotiations had not begun. The most important unsettled question was whether the United States should demand that Spain cede the Philippine Islands.

Hay was not an early advocate of imperial expansion. Although he may have approved of efforts in the 1860s to annex Santo Domingo (now Dominican Republic), his democratic idealism of the early years militated against imperialism. In 1884 he penned a poem urging the United States not to take Hawaii, but when in 1893 Grover Cleveland decided to reject Harrison's treaty of annexation, Hay strongly criticized the action.

As for the Philippines, like most Americans Hay had given little thought to the archipelago prior to May 1898. He soon came to favor retention of a coaling station, and during the summer his fears of German ambitions in the Pacific drove him toward annexation. In addition, the British wanted the United States to annex the islands, and Hay was aware of possible commercial advantages that might flow from annexation. The president's thought evolved in a manner very similar to Hay's, and in late October he demanded the cession of the entire archipelago.

When the Philippine-American War began in February 1899, Hay supported military efforts to defeat the Filipino resistance. He portrayed the Filipino leaders as venal and incompetent and in the spring of 1899 rejected advice that, since the United States had achieved major military victories in the initial encounters, it ought to make conciliatory gestures to bring about a settlement. American authority, he stated, would be established by military means. Hay defended America's imperial course against a chorus of bitter, sometimes personal, attacks from anti-imperialists. Some of the critics were his close friends, including Andrew Carnegie, Henry Adams, Twain, and Howells.

Acquisition of the Philippines heightened American interest in China. Fears that China might be divided among the European powers and Japan led Hay to issue the famous Open Door notes in 1899. The notes urged the powers to avoid discrimination against other countries within their spheres of influence and was implicitly hostile to the very idea of spheres. The next year, when Chinese traditionalists (Boxers) rose in revolt to challenge Western influence, the powers, including the United States, sent troops to relieve the besieged Western legations in Peking (Beijing). Fearing that this action might lead the powers finally to divide China, Hay sent another Open Door note that committed the United States to the maintenance of China's "territorial and administrative entity," thus challenging the spheres directly. Although Hay announced that all of the powers had accepted the American position, in fact none of the powers accepted it without reservations or exceptions. Hay knew that a successful policy required available force, and in one of his few disagreements with the president, he opposed withdrawing American troops from China.

Given the limited tools that he possessed, Hay's attempt to restrain the powers in China was probably the most he could have done, but whether it was the Open Door policy that preserved China is questionable. More likely the rivalries among the powers prevented a full-scale division. The Open Door notes also demonstrated Western contempt for China, which was not even informed of the policy in advance. Nevertheless, Hay's China policy was immensely popular in the United States and was an important political success for the McKinley administration.

Hay sought unsuccessfully to align his China policy with that of Great Britain but took the British point of view in South Africa, where in 1899 the Boer War broke out between Britain and Afrikaners. Although the American public sympathized with the Boer rebellion, Hay stood steadfast against it. He inhibited Boer efforts to acquire material and political support in the United States, fired American consuls who sympathized with the Boers, and appointed his own son, Adelbert Stone Hay, as consul at Pretoria.

In the western hemisphere, Hay was able to bring Britain and the United States closer by working to remove points of disagreement. The disputed boundary between Alaska and Canada was the most difficult to resolve. Originally a matter of small concern, the discovery of gold in the region made a specific delineation important.

Hay, primarily interested in forging strong Anglo-American ties, was willing to compromise. When an Anglo-American Joint High Commission proved unable to resolve the boundary issue, Hay wanted to submit it to binding arbitration but the Senate resisted, and the Canadians were intransigent. He then suggested leasing a strip of land that would allow the Canadians railroad access to the sea, a major Canadian objective. The Senate was strongly opposed, however, and the best Hay could do for the moment was to negotiate a modus vivendi with Britain that established temporary demarcation lines in crucial areas.

Another issue involved the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850, which provided that any canal across the Central American isthmus be jointly owned and operated by Britain and the United States. Many Americans wanted any canal to be American-controlled. After the modus vivendi on the Alaska boundary was reached in October 1899, the British accepted a new isthmian treaty negotiated by Hay and the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Pauncefote. However, jingoist Americans, including New York governor Theodore Roosevelt, felt that the treaty was insufficiently nationalistic and forced Hay to renegotiate it. After further British concessions, the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty was finally approved in December 1901. The British gave up their rights to mutual control of a canal.

Meanwhile, Hay sought to resolve the Alaska issue in an amicable way but by then Theodore Roosevelt, who thought the American position was unassailable, was president. Under great pressure, in 1903 the British accepted the essence of the American claim after a quasi arbitration. It was further evidence of the British determination to conciliate the United States, but Hay felt a settlement could have been reached with much better grace.

Although Hay thought Roosevelt too pugnacious on the boundary question, generally the two men got along well, as the acquisition of the Panama Canal Zone demonstrated. Freed by the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty of external restraints, Hay negotiated a treaty with Colombia (Panama then being a province of that country) for a canal zone. When Colombian legislators rejected the treaty, Hay preferred to investigate an alternative route through Nicaragua but offered no objection when Roosevelt decided to intervene directly in Panama. When in November 1903 Panamanians rose in revolt against Colombia, Hay supported Roosevelt's intervention and quickly negotiated an American-controlled canal zone with Panama.

With the completion of the canal treaty, Hay's creative days as secretary of state were over. He suffered increasingly from poor health, and Roosevelt more often controlled foreign policy directly. Hay, however, left a record of solid diplomatic achievements. He forged closer Anglo-American ties, presided over the acquisition of an overseas empire in the Pacific, issued the Open Door notes, and expanded American influence in Latin America. He died at Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire.

Bibliography

The two major collections of Hay papers are at Brown University and the Library of Congress. Substantial numbers of Hay letters are available in other collections, including the Wadsworth Family Papers, the Whitelaw Reid Papers, the Henry White Papers, and the Joseph Choate Papers, all in the Library of Congress. For descriptions of these and other collections of Hay's letters, see the bibliographical essays in Kenton Clymer, John Hay: The Gentleman as Diplomat (1975), and Patricia O'Toole, The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends, 1880-1918 (1990). Hay's diplomatic correspondence is available at the National Archives.

There is no complete published edition of Hay's letters and diaries. Shortly after Hay's death Clara Hay and Henry Adams published an unreliable edition, Letters of John Hay and Extracts from His Diary (1908). More reliable, but limited in scope, are Tyler Dennett, ed., Lincoln and the Civil War in the Diaries and Letters of John Hay (1939); George Montiero, Henry James and John Hay: The Record of a Friendship (1965); and George Monteiro and Brenda Murphy, eds., John Hay-Howells Letters: The Correspondence of John Milton Hay and William Dean Howells 1861-1905 (1980). William R. Thayer, The Life and Letters of John Hay (1915), also reproduces many Hay letters. A nearly complete bibliography of Hay's own writings by William Easton Louttit, Jr., is appended to the most complete biography available, Dennett, John Hay: From Poetry to Politics (1933).

There are several other good biographies. Howard I. Kushner and Anne Hummel Sherrill, John Hay: The Union of Poetry and Politics (1977), emphasizes the importance of Lincoln. A critical analysis of Hay's social thought and diplomacy is Clymer, John Hay (1975). The best account of Hay's life among the Five of Hearts is O'Toole, The Five of Hearts (1990). For Hay's relationship with Henry Adams one should not overlook Harold Dean Cater, ed., Henry Adams and His Friends: A Collection of His Unpublished Letters (1947).

Other noteworthy accounts of Hay include Robert L. Gale, John Hay (1978); Lorenzo Sears, John Hay: Author, Statesman (1914); Alfred L. P. Dennis, "John Hay," in The American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy, ed. Samuel F. Bemis (1928); and Foster R. Dulles, "John Hay," in An Uncertain Tradition: American Secretaries of State in the Twentieth Century, ed. Norman Graebner (1961). Important analyses of The Bread-winners include Frederic Cople Jaher, "Industrialism and the American Aristocracy: A Social Study of John Hay and His Novel, The Bread-winners," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 65 (Spring 1972): 69-93, and Charles Vandersee's introduction to The Bread-winners (1973). An obituary is in the New York Times, 2 July 1905.

Kenton J. Clymer

Back to the top

Citation:

Kenton J. Clymer. "Hay, John Milton";

http://www.anb.org/articles/05/05-00888.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Jul 29 2013 15:00:06 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.