Annie Fields

Fields, Annie Adams (6 June 1834-5 Jan. 1915), literary hostess, author, and social reformer, was born Ann West Adams in Boston, Massachusetts, the daughter of Zabdiel Boylston Adams and Sarah May Holland, both descended from prominent early Massachusetts settlers. Her father was a Boston physician who also taught at Harvard Medical School and served on the Boston school board. Annie's childhood pleasures included easy access to books and Sunday visits to such distinguished relatives as the Adamses of Braintree. At George B. Emerson's celebrated School for Young Ladies, where her training ranged from the classics and modern languages to experimental botany and "mental arithmetic," she also internalized two imperatives that would thereafter often conflict: self-fulfillment and selfless service.

In November 1854 twenty-year-old Ann West Adams married James Thomas Fields, a man of thirty-seven who was the "literary partner" in Boston's most important publishing firm, Ticknor and Fields; the couple had no children. Immediately, she became part of New England's burgeoning literary life and felt swept "upon a tide more swift and strong and all enfolding than her imagination had foretold." Two years later, the couple bought the brownstone house on Charles Street where their guests included many of the period's most celebrated authors.

In June 1859 the Fieldses embarked on a yearlong trip abroad that was at once a delayed honeymoon and a business trip. For Annie, it also became a kind of finishing school. She made friends with English writers she had long revered, most notably Charles Dickens and Alfred Tennyson; she reveled in the scenic and cultural splendors of England and the Continent; and her husband felt proud of the "great strike" she made wherever they went. Annie would later enjoy other trips abroad, with James and with Sarah Orne Jewett, but none would be as transforming. By the time she returned on the same boat that carried Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sophia Hawthorne, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, Annie Fields's self-confidence, sophistication, and circle of friendships had dramatically increased.

Her hospitality at Charles Street soon became legendary. Within a few days she might give a reception for fifty in her book-lined drawing room, a dinner for twenty in her flower-filled dining room, and a few breakfasts and lunches for overnight guests. Among her regular visitors were such literary celebrities as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Harriet Beecher Stowe and also many of the period's most eminent editors, statesmen, scientists, ministers, artists, actors, and musicians. Her hospitality was at its height in the 1860s, and it continued after James Fields's retirement in 1870, both at Charles Street and (after 1875) at the Fieldses' seaside "cottage" in Manchester. Even during the decades after her husband's death when Sarah Orne Jewett shared her life, the flow of guests at both houses continued to include old friends such as Whittier and Matthew Arnold and newer ones such as Willa Cather.

Annie Fields also undertook another kind of literary service during the 1860s. When James Fields became editor of the Atlantic Monthly in 1861, soon after Ticknor acquired it, he transformed it into a major periodical. Annie often served as James's unofficial literary assistant. At his request, she might correspond with a new contributor such as Rebecca Harding Davis, pass judgment on a submission from Henry James, or convey information about deadlines and publication dates. Some contributors directly enlisted Annie's help, as when Stowe set her a research task or Whittier asked if his latest poem seemed appropriate for the Atlantic; Fields herself occasionally solicited manuscripts. Sometimes she also served Ticknor and Fields by reading book manuscripts, as when her enthusiasm for Elizabeth Stuart Phelps's The Gates Ajar helped launch a new career.

Fields's journals became an even more sustained way of serving her husband and the reading public. Her 1859-1860 diary includes lively records of her encounters with notables such as Dickens, Tennyson, Hawthorne, and Stowe. Then in 1863, out of a renewed commitment to "record something of the interesting events in literature which are constantly passing under my knowledge," she began keeping a "journal of literary events and glimpses of interesting people" and maintained it for more than fourteen years. As a conscientious custodian of literary life, she preserved intimate glimpses of the "interesting people" she encountered: of a gaunt Hawthorne reminiscing about his childhood a few months before he died; of Stowe's nervousness before giving her first public lecture; and of the first time Dickens dined at Charles Street and reduced even the somber Professor Louis Agassiz to helpless laughter. James T. Fields drew heavily on her journals after he retired in 1870, when he prepared the essays on Dickens and Hawthorne that appeared first in the Atlantic and then in Yesterdays with Authors (1872)--his most important contributions to literary history. Later Annie Fields herself would draw on them for her own memoirs of writers she had known and loved, and her literary executor Mark A. DeWolfe Howe followed her lead in Memories of a Hostess: A Chronicle of Eminent Friendships (1922), a biography that still remains useful.

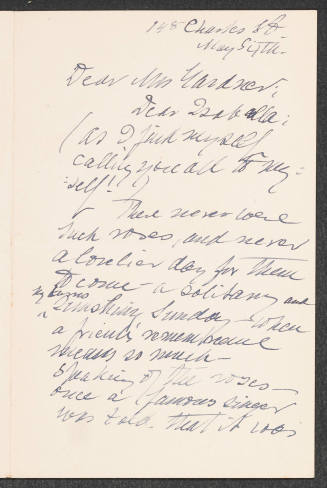

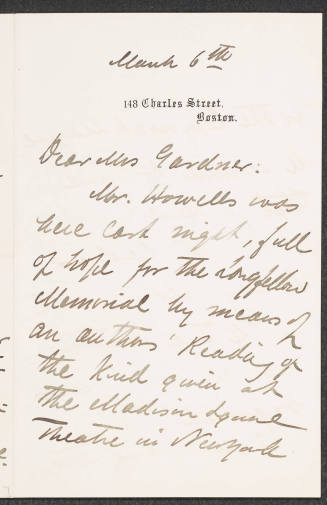

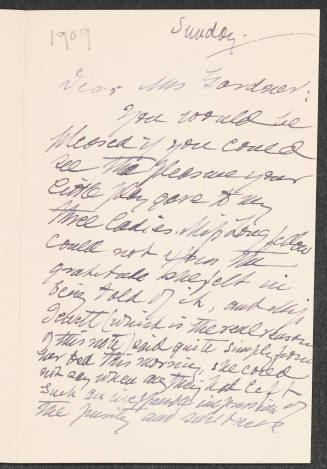

Annie Fields's voluminous correspondence with men and women on both sides of the Atlantic offers privileged entry into her life and theirs. Clearly, that correspondence was a mode of self-expression and sympathetic nurturance. It is also a rich literary resource. To a virtually unknown Staten Island woman named Laura Johnson, for example, Fields sent deeply sympathetic accounts of Hawthorne's last visits to Charles Street. Her comments to Rebecca Harding Davis about George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe inform us about nineteenth-century women writers' networks and about their individual struggles to develop their talents without abandoning "womanly" responsibilities.

Despite her own genteel reticence, Fields herself occasionally complained that her responsibilities thwarted her poetic "genius." Her husband offered support and encouragement by publishing eighteen of her lyrics in the Atlantic and by arranging separate publication of three longer and more ambitious works: Ode on the Inauguration of the Great Organ in Boston, Nov. 2, 1863. Recited by Miss Charlotte Cushman (1863); a dramatic idyll about the Shakers (which she would revise for the English Macmillan's) titled The Children of Lebanon (1872); and a dramatic sketch inspired by her mother's death, The Return of Persephone (1877). Even after James Fields retired from publishing, the work of Annie Fields was accepted by editors of the Atlantic and such prestigious periodicals as Harper's and Scribners. Houghton Mifflin published Orpheus: A Masque (1900) as well as two collections of her poems: Under the Olive (1881) and The Singing Shepherd and Other Poems (1895). Only rarely do we encounter in her writing the distinctive voice and original vision that modernists admire. But her poems are well crafted and high minded: they demonstrate mastery of period conventions, and contemporary critics such as Edward Stedman could praise her appropriation of Greek meters and compare her to Tennyson and John Keats.

She did not fare as well with her anonymous novel Asphodel, which her husband published in 1866. Though Lucy Larcom admired it as a study of women's friendships and Thomas Bailey Aldrich as a roman à clef about James Russell Lowell, Sophia Hawthorne and other friends who did not know who had written it condemned its weak plotting and thin characters. Perhaps because of that blow to her pride, Annie Fields never produced another novel.

But two years later came an entirely different kind of initiative, her first venture into the public sphere and the beginning of a new career as a social reformer. As a direct consequence of her lifetime commitment to public service and also as a way to channel her grief at the death of Charles Dickens, Fields established a workers' coffeehouse as an alternative to barrooms, a place where a worker could buy a good cup of coffee for a nickel and have a comfortable place to sit. The name she chose--the Holly Tree--implicitly paid tribute to Dickens, who had included in his 1867 reading tour a cheerful Christmas story titled "Boots at the Holly Tree Inn." Her own Holly Tree was a way to put Dickens's humanitarian ideals into practice and to modestly improve the lives of slum dwellers. Before long, she opened other Holly Trees and a women's residence, and philanthropists in other cities soon followed suit.

In 1872 a great fire devastated Boston's inner city, putting thousands out of work, and Fields became an increasingly venturesome entrepreneur. She raised enough money to maintain her home for working women when most of its occupants lost their jobs, and she opened a cooperative sewing room that employed up to thirty seamstresses. She also began visiting other unemployed workers to determine their individual needs. This led to her major philanthropic initiative. In 1875 she and her friend Mary Lodge founded the Cooperative Society of Visitors, adapting a system already established in England and Germany predicated on home visits to the needy and an efficient central administration committed to promoting self-sufficiency. From the start, Fields herself served as an officer and a visitor and also enlisted other volunteers--among them William Dean Howells, the renowned minister Phillips Brooks, and her sister Louisa Beal. The scope of her commitment expanded at the end of the decade when the society was absorbed into the larger and more influential Associated Charities of Boston.

As early as 1872 Fields wrote an article about the Holly Tree Coffee Rooms for the Christian Union, expanding her role as a professional writer to include her role as a reformer. Before long, periodicals such as Harper's and the Atlantic welcomed and even solicited articles from her about social reforms. Her most influential contribution to the literature of social reform was a book about the Associated Charities. How to Help the Poor, published by Houghton Mifflin in 1883, went through three printings and sold more than 22,000 copies.

Fields's overlapping commitments to reform, to education, and to self-fulfillment for herself and others also generated other initiatives. She taught classes for working women at the North End Mission; she helped her husband arrange a series of college-level courses for women; she supported Boston University as the area's first coeducational institution of higher learning; she advocated medical education for women; she organized a club for women writers; and as chair of the Massachusetts committee, she solicited and selected exhibits for the Women's Pavilion at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. During the mid-1870s she sometimes accompanied her husband on his lecture tours. Despite her own ladylike reluctance to mount the public platform, she delivered acclaimed lectures in and beyond Boston on reforms she supported, frequently but not exclusively on the Associated Charities.

Annie Fields's greatest trauma was the death of her husband in the spring of 1881. Life then seemed almost unendurable, but by midsummer she was renewing her commitment to self-fulfilling service by preparing the tribute to his life, James T. Fields: Biographical Notes and Personal Sketches. A few months later she entered another loving partnership, with a writer eighteen years her junior--Sarah Orne Jewett. Until Jewett's death in 1909, the two women spent most of each year together, in Charles Street, in Manchester, and as traveling companions. Maintaining their separate interests and careers, together they entertained old friends and new ones, wrote at nearby desks, and criticized each other's work. As Henry James put it, their "reach together" was firm and easy. During all those years, Fields remained an active charity worker and an increasingly productive woman of letters, publishing poems and essays until her death. Her most enduring literary contributions are the biographies of writers whose lives she had shared, including the two collections A Shelf of Old Books (1895) and Authors and Friends (1896), Letters of Celia Thaxter (1895), Life and Letters of Harriet Beecher Stowe (1897), Nathaniel Hawthorne (1899), Charles Dudley Warner (1904), and Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett (1911).

She died at her Charles Street home. As she stipulated in her will, the house was demolished but not the garden she hoped future generations would enjoy; the Manchester house and its contents went to her nephew; many paintings and other works of art went to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and a few to old friends; many books and manuscripts went to Harvard and Dartmouth; and the largest of her financial bequests went to the Associated Charities. As one obituary concluded, "Her long life, active and useful to the end, bridged the most brilliant half century of Boston's three hundred years--'all of which she saw and a part of which she was.' "

Bibliography

Major collections of Annie Fields's letters and manuscripts are at the Huntington Library, the Houghton Library, the Boston Public Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the New York Public Library. Smaller collections are at the Boston Athenaeum, the Schlesinger Library, the Library of Congress, the Morgan Library, the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, and various university libraries. The sixty-one diaries at the Massachusetts Historical Society--which cover the years 1859-1860 and 1863-1877 in dense detail and also include entries for 1896, 1898, 1905, and 1907-1912--are available on microfilm.

Friends' tributes include Therese Bentzon, "Mrs. J. T. Fields: Drawing-Rooms and Interiors," in The Condition of Woman in the United States (1895); Willa Cather, "148 Charles Street," in Not under Forty (1936); Henry James, "Mr. and Mrs. James T. Fields," Atlantic Monthly, July 1915, pp. 21-31; and the opening chapter of Harriet Prescott Spofford, A Little Book of Friends (1916). Useful secondary studies include Judith A. Roman, Annie Adams Fields: The Spirit of Charles Street (1990); Barbara Ruth Rotundo, "Mrs. James T. Fields, Hostess and Biographer" (Ph.D. diss., Syracuse Univ., 1968); James C. Austin, Fields of the Atlantic Monthly (1953); William S. Tryon, Parnassus Corner (1963); Paula Blanchard, Sarah Orne Jewett (1995); and Nathan Irvin Huggins, Protestants against Poverty (1971). Rita K. Gollin's studies include "Annie Adams Fields," Legacy 4, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 27-33; "Mrs. and Mr. James T. Fields," in Patrons and Protegees (1988).

Rita K. Gollin

Back to the top

Citation:

Rita K. Gollin. "Fields, Annie Adams";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00538.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:36:36 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.