Owen Wister

Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1860 - 1938, Saunderstown, Rhode Island

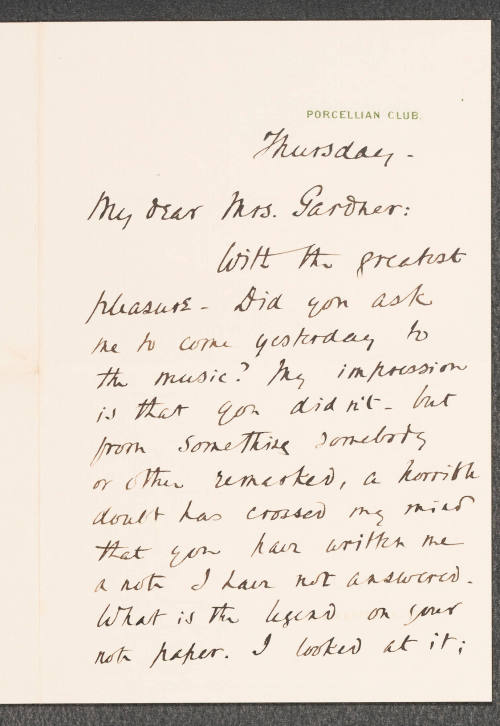

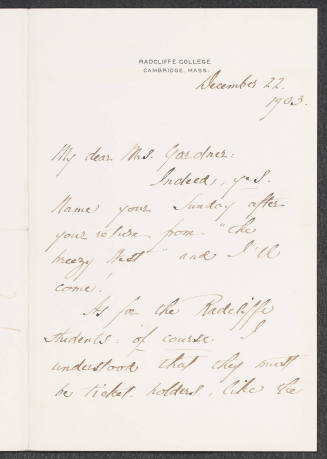

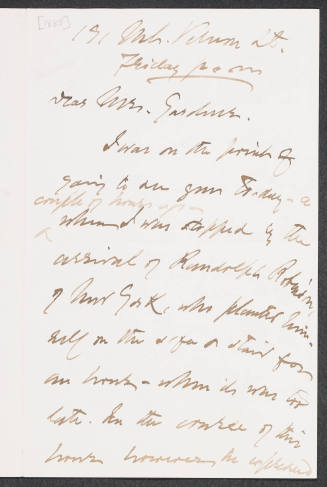

Both at the exclusive St. Paul's School, in Concord, New Hampshire, which he attended from 1873 to 1878, and then at Harvard, Wister's chief interest was in music, although his social interests also took much of his time. While at Harvard, Wister was welcomed into the higher reaches of Boston society, and within Harvard itself he formed lifelong relationships through his clubs. His friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, an older classmate, would prove to be particularly rewarding and enduring.

Graduating summa cum laude from Harvard in 1882, Wister intended to pursue a career in music. To that end he returned to Europe. His compositions were approved by Franz Liszt, to whom he had secured an introduction through his grandmother Fanny Kemble. His studies were further encouraged by Antoine-François Marmontel and Ernest Guiraud, teachers to some of the most famous European composers. Wister's one-act comic opera, La Sérénade, was performed in Paris in early 1883, and he then commenced work on a longer opera, Montezuma.

Wister's relationships with his parents had been strained for some time, his mother being particularly critical and demanding and his father being suspicious of his son's ambitions. Later in 1883 Dr. Wister secured a position for his son in a Boston brokerage. Although he apparently almost immediately relented and agreed to support Owen's studies in Paris, Wister now abandoned music as a profession. For the rest of his life, however, he continued to compose music and to write music commentary. Back in the United States, he worked in Boston and then spent a brief time as a clerk in a Philadelphia law office. He had long suffered from varieties of ill health, including bouts of severe headaches and episodes of semiparalysis of the face. In the summer of 1885, on the advice of Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, and, accompanied by two of his mother's spinster friends, he took a trip to Wyoming for a rest cure.

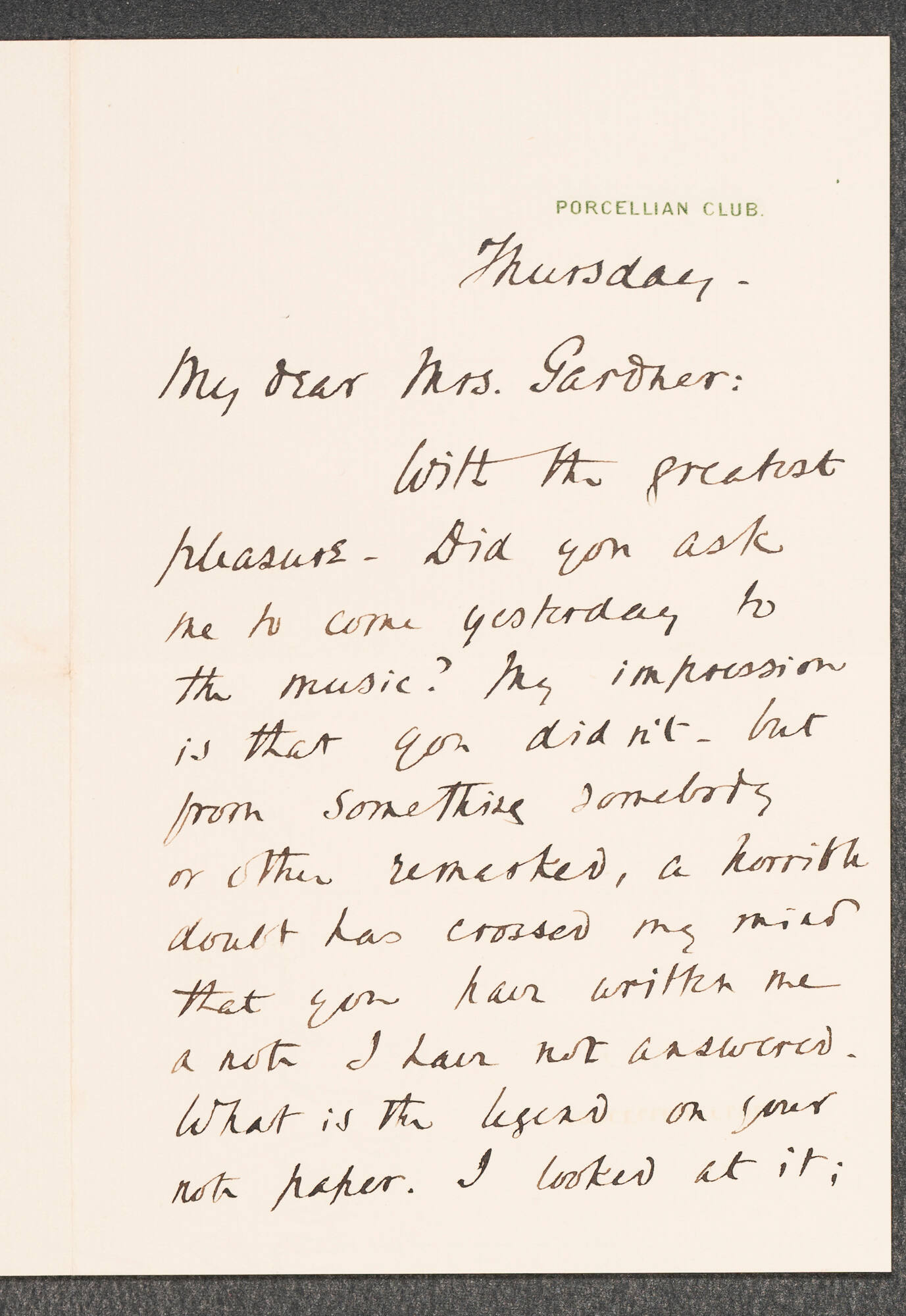

That trip at once restored Wister's health and changed his life. ("I'm beginning to be able to feel I'm something of an animal and not a stinking brain alone," he wrote in his journal soon after his arrival at the ranch where he stayed.) At the end of the summer he returned east to attend Harvard Law School, from which he graduated in 1888. He then settled in Philadelphia, where he practiced law sporadically. Wyoming, however, had been an inspiration, and he returned to the West repeatedly, recording his encounters with cowboys and others, anecdotes he heard, and his observations of details of western life. In the fall of 1891, after his fifth summer in the West, he drew upon his notebooks for the first of his western tales, "Hank's Woman" and "How Lin McLean Went East," both published in 1892, the first in Harper's Weekly and the second in Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Henceforth writing became a daily occupation for Wister, and hereafter, although in fact from his midforties onward he would largely abandon specifically western themes, Wister would become famous for his western tales.

Like many of the stories, sketches, and essays to follow, the two early tales pointed to fundamental differences between western manners and assumptions on the one hand, and those of the traditional East on the other, leading sometimes to tragic consequences and sometimes to comedy. "Hank's Woman" is a somber story about a cowboy who has married a religious, tradition-bound Austrian maid-servant who had been abandoned in the West by her European employers. The union is unlikely from the beginning, and ends with the killing of Hank by his wife, followed by her own accidental death as she tries to dispose of the body. "How Lin McLean Went East" is a brief comic sketch in which the rapscallion gambling and womanizing cowboy Lin visits his successful businessman of a brother in Boston, who is embarrassed by his ways and his appearance, whereupon Lin returns to the West.

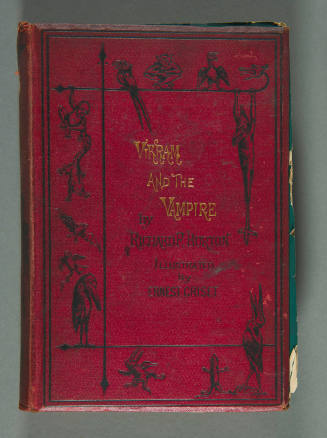

Wister combined and elaborated his various tales in Red Men and White (1896), Lin McLean (1898), and The Jimmyjohn Boss (1900), and the novel The Virginian (1902), which he dedicated to Theodore Roosevelt. The Virginian, with its lanky, competent, gentlemanly and soft-spoken but nonetheless ominous hero, proved to be the archetypal American western, while "the Virginian" himself became the basic model for the cowboy in fiction and film to come. In this original, however, he is a fairly complex character and not merely a wild man from the West. Wister comments at length on his aristocratic bearing. Moving through his various adventures, the Virginian is sometimes tender and is often shy. He is given to ironical joshing and sometimes to practical jokes, but at the same time he is so proud a man that he will kill rather than accept even a mild insult. Thus in the most famous line of dialogue in the novel, after the villain Trampas accuses him of cheating at poker saying, "Your bet, you son-ofa----," he draws his pistol and says, speaking gently but with the sound of death, "When you call me that, smile!" Near the end of the novel, moreover, in a famous duel scene, in fact he will kill Trampas. The novel was a great best seller both in its own day and subsequently. It was adapted to the stage, made into movies, and in the 1960s became the basis for a television series.

At the end of this archetypal western, the hero does marry the eastern schoolmarm, herself the daughter of a distinguished Vermont family with ancestry going back to Revolutionary days, and, far from riding off into the sunset, he becomes a rich and important man with a grip on many enterprises. Here, as in an 1895 essay written in collaboration with Frederic Remington, "The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher," Wister would seem to have been as much intent upon recovering supposedly lost values and character for the East as in portraying the West for itself. The Virginian is the appropriate mate for a descendent of a Revolutionary War hero. In the 1895 essay the cowboy is seen to be the true remaining Anglo-Saxon, "still forever homesick for out-of-doors," and a potential savior for an East that, in Wister's view, had been adulterated by new immigrants.

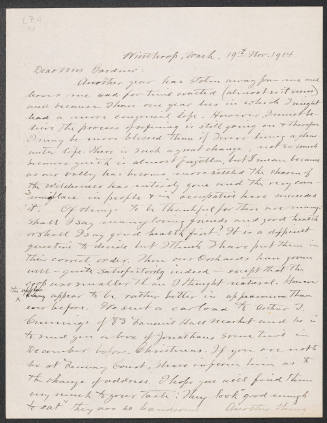

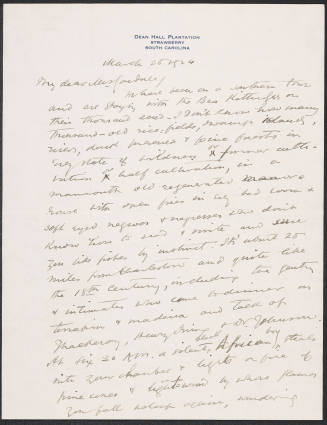

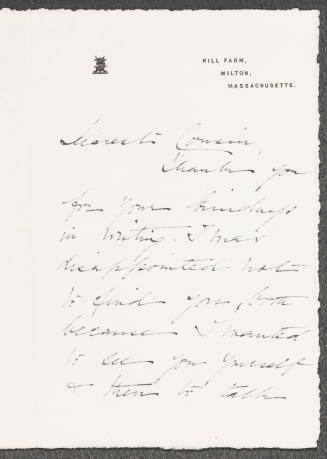

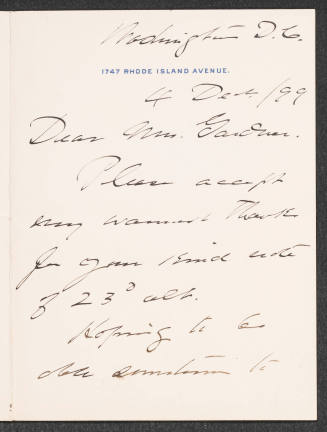

In 1898 Wister married a distant cousin, Mary Channing Wister, the great-granddaughter of William Ellery Channing (1780-1840). As might be expected given the social position which he occupied with his wife, Wister came to be ever more conservative in his views. He wrote one more novel, Lady Baltimore (1906), in which he expressed appreciation of the aristocratic society of Charleston, South Carolina, to which he himself had access as a descendent of Pierce Butler. His other writing ranged from a lengthy comic sketch Philosophy 4 (1903), a baldly anti-Semitic tale about a couple of Harvard undergraduates, to How Doth the Simple Spelling Bee (1907), which attacked the simplified-spelling movement, to a brief three-act satire on Prohibition, Watch Your Thirst (1923). In 1904 he became vice president of an organization called the Immigration Restriction League. During World War I, he published The Pentecost of Calamity (1915), in which he attacked supposed German barbarism and urged American participation in the war. In A Straight Deal, or The Ancient Grudge (1920), he vehemently attacked supposed anti-British feeling in the United States, following that book however with a less angry Neighbors Henceforth (1922) in which he urged American cooperation with the Allies.

Wister also wrote accounts of three presidents: Ulysses S. Grant (1900), The Seven Ages of Washington (1907), and Roosevelt: The Story of a Friendship, 1880-1919 (1930), although the last was as much about Wister himself as it was about Theodore Roosevelt. His collected works were published in a standard edition of eleven volumes in 1928.

A week after his seventy-eighth birthday, at his summer home in Saunderstown, Rhode Island, Wister was struck by a cerebral hemorrhage and died the next day. His wife had died in childbirth, in 1913. Wister was buried in Philadelphia, next to his wife's grave. He was survived by five of his six children.

Bibliography

The primary collection of Owen Wister papers is in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Other letters and papers are in the Houghton Library of Harvard University and the American Heritage Center of the University of Wyoming. For Wister's journals see Fanny Kemble Wister, ed., Owen Wister Out West: His Journals and Letters (1958). Letters and documents are reprinted in Ben Merchant Vorpahl, My Dear Wister: The Frederic Remington-Owen Wister Letters (1972). Both books contain biographical essays. The most substantial biography of Wister is Darwin Payne, Owen Wister: Chronicler of the West, Gentleman of the East (1985). Earlier biographies are John L. Cobbs, Owen Wister (1984), and Richard W. Etulain, Owen Wister (1973), both of which have bibliographies. Important discussion of Wister's interest in the West along with that of other Eastern patricians is to be found in Edward G. White, The Eastern Establishment and the Western Experience: The West of Frederic Remington, Theodore Roosevelt, and Owen Wister (1968).

Marcus Klein

Back to the top

Citation:

Marcus Klein. "Wister, Owen";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01795.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:56:41 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

New York, 1862 - 1933, Poughkeepsie, New York

Washington, D.C., 30 December 1841 - 5 December 1914, Philadelphia

active Wellesley Hills, Massachusetts,1858 - 1930

Montpelier, Vermont, 1837 - 1917, Washington, D.C.

Torquay, Devon, England, 1821 - 1890, Trieste, Italy