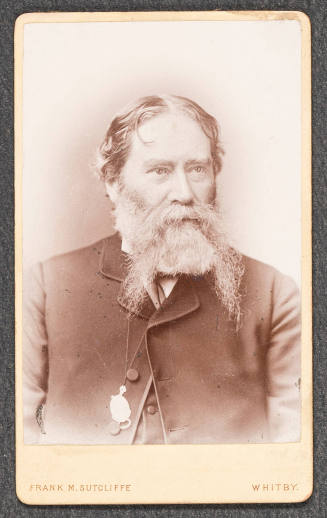

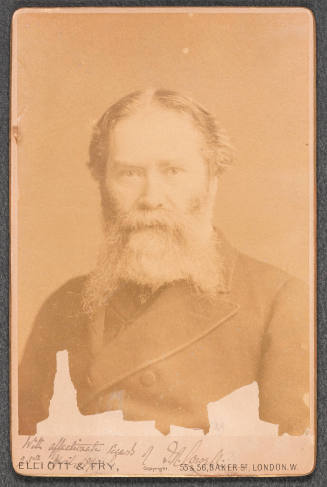

James Russell Lowell

Lowell, James Russell (22 Feb. 1819-12 Aug. 1891), author and diplomat, was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the son of Charles Lowell, a liberal Congregational minister, and Harriet Brackett Spence. Among New Englanders who were apt to take ancestry seriously, the Lowell family was already firmly established in the region's ecclesiastical and legal annals. During the nineteenth century the Lowell name became synonymous with manufacturing wealth and State Street trusts, but Charles Lowell's descendants benefited little from this tradition. Their area of prominence was in literature; both James Russell Lowell's sister Mary Lowell Putnam and brother Robert Traill Spence Lowell were accomplished writers, though neither enjoyed the public recognition of their brother.

Lowell's early education in Cambridge met the best standards of the day, and he entered Harvard in 1834. His studies there were not particularly challenging, and he soon gave more attention to social and literary matters than his preceptors thought wise. Spoiled and immature, Lowell frequently ran afoul of the Harvard authorities; eventually his violation of college regulations and neglect of his studies led to his suspension several months before graduation, and he was sent to nearby Concord to finish his studies under the direction of the local minister. This was by no means severe punishment. Lowell's chief regret was that his enforced absence from Cambridge prevented him from fulfilling in person the office of class poet, an honor voted him by his classmates in recognition of his budding literary talents, which had already been displayed in essays and poems published in Harvardiana, the college magazine of which Lowell was an editor. But neither these pieces nor the Class Poem (1838) reveal a literary power altogether exceptional for the time. Even the ardent passion for literature displayed in this early work and the earnest satire that marks the best parts of the Class Poem are fairly typical of undergraduate performances of that day.

No matter how great Lowell's literary interests and talent were at the time of his graduation, they would not have been sufficient to ensure him a vocation in literature in the United States during these antebellum years; like others with similar tastes and desires, he was forced to earn his way in the world. Because the ministry, medicine, or business could not long hold his interest (though he considered all three), he finally settled on law. Awarded the bachelor of laws degree at Harvard's Dane Law School in 1840, and admitted to the Massachusetts Bar two years later, Lowell attempted to establish a legal practice in Boston, but within six months he became convinced that for him law was just as impractical as, and probably even more unprofitable than, a literary life, so he gave up his practice and turned to literature for support.

Periodical publication in America was making significant gains during the 1840s, and Lowell's poems found ready acceptance in the leading literary journals, such as the Southern Literary Messenger, Graham's Magazine, and the United States Magazine and Democratic Review. While the money paid for his work was small and irregular, the reputation Lowell won during these early years as a lyric poet lasted his lifetime. His first volume of verse, A Year's Life (1841), was followed soon after by Poems (1844), Poems: Second Series (1848), and the greatly popular Vision of Sir Launfal (1848). The critical response to Lowell's verse was unusually favorable, and N. P. Willis did not greatly exaggerate when he later called Lowell the best-launched poet of his generation. But this early recognition of Lowell's poetic talents was undiscriminating, far more patriotic than critical. Nor are the deficiencies that characterized these early poems--technical infelicities and irregularities, didacticism, obscurity, and affected literary tone--ever entirely absent even from his more mature performances, especially those written in the lyrical mode. Later Lowell did write some distinguished poetry in a philosophical, public vein, particularly The Cathedral (1870), the magisterial Ode Recited at the Commemoration of the Living and Dead Soldiers of Harvard University (1865), and the 1874 elegy occasioned by the death of his friend Louis Agassiz, but his achievement in serious verse is small. Lowell himself was aware of his limitations as a poet, and he increasingly expressed to friends his misgivings. His reference to the volume of poems Under the Willows (1869) as "Under the Billows or dredgings from the Atlantic" is not only a masterful pun (many of the poems having first appeared in the Atlantic Monthly), but also accurate in describing the forced quality of much of the book's contents.

Lowell soon discovered that his verse was not likely to provide him with a financial basis on which to build the life he desired, especially marriage to the poet Maria White (Maria White Lowell) of Watertown, Massachusetts, to whom he had become engaged in 1840. Hoping to profit from the burgeoning public interest in periodicals, Lowell, in partnership with his friend Robert Carter (1819-1879), founded a magazine of his own, the Pioneer, the first number appearing in January 1843. His expectations for the monthly, however, were more than just financial; as he wrote in the magazine's prospectus, it would provide "intelligent and reflecting" readers with something better than "the enormous quantity of thrice-diluted trash" that was the ordinary fare of magazines at the time. Lowell solicited and received contributions from an impressive group of writers, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Jones Very, John S. Dwight, and Elizabeth Barrett in England, but an eye problem that required his absence from Boston and financial misunderstandings with the magazine's publisher caused the venture to fail within three months. After such an ambitious beginning, the failure of what he had envisioned to be the great American magazine was an enormous disappointment, especially since the debt he incurred delayed his marriage to Maria White until December 1844.

No doubt Lowell's defeat in the economic chance-world of periodical publishing contributed to his growing political radicalism; and though Maria White was not the source of his antislavery sentiments, as was sometimes claimed, she did encourage her fiancé to take a more active role in reform movements, bringing Lowell increasingly into the public arena. He became a chief editorial writer in the 1840s for the Pennsylvania Freeman and the National Anti-Slavery Standard, and during that decade he published scores of prose articles and poems in support of abolition and other liberal causes. Generally in sympathy with the Garrisonian wing of the antislavery movement, Lowell attacked not only slavery, but also the church, the Constitution, and, on occasion, even the Union itself. But his tolerance for human frailty and his sense of irony and humor prevented him from being as unrelenting a reformer as many of his compatriots thought desirable. His shrewdness and wit found their natural expression in satire, which was as likely to be turned against the reformers as against the objects of their zeal. Humorous satire, Lowell believed, was a means to establish equilibrium in a world out of balance. He looked on creation with a laughing eye, a point of view not generally favored by polemicists. In his best poetry and essays, even in the stories remembered and told afterward about him, humor is never absent, and its range is as varied as the occasions that elicited it, witty and learned at times, boisterous and close to bawdy at others.

Nowhere is Lowell's humor better revealed than in The Biglow Papers (1848), a curious little masterpiece of political satire occasioned by the war with Mexico (1846-1848). In the beginning the book was no more than some clever newspaper verses written in Yankee dialect and printed under the name of Hosea Biglow, an upcountry farmer whose practical good sense far outshines the patriotic cant of the supporters of the war (which Biglow, like Lowell, saw as an imperialistic drive to expand westward the area of slavery). The Yankee oracle, a regional variety of the cracker-barrel philosopher so popular in the Jacksonian era, was by no means new to American literature, though he spoke generally in prose rather than verse. Lowell's contribution to the tradition was in turning this rustic figure into an effective and memorable poet, in raising the vernacular voice to a level not only of trenchant political satire but of high artistic expression. Immediately successful, the verses were copied and quoted, imitated and admired, even by those out of sympathy with Lowell's politics, a response that led Lowell to decide to make a book out of the Biglow material. For this he created two other Yankee voices: the picaresque Birdofredum Sawin, a townsman of Hosea who has hurried off to enlist, assured by the promise of wealth and adventure to be had in Mexico, and Homer Wilbur, a pedantic but well-meaning Congregational minister whose job it is to bring the verses before the public in proper form. The result is a work that transcends generic categories: a medley of voices and moods, prose and verse, classic English, Yankee speech, and tortured Latin. Some of it is dated, as one would expect of occasional satire, but much is timeless, classic, the finest political satire of nineteenth-century America.

By the time of the Compromise of 1850 Lowell had largely withdrawn from active participation in reform movements, though his sympathies could still be stirred by the tide of liberalism that was then redefining the relationship between individuals and their societies in Europe and the United States. But like many others, most notably his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, he believed that reform must first be manifested within the self. Lowell was also still determined to find within the structures of American economic life a way to maintain his and his family's well-being through a devotion to literature, if not solely as a poet, then as a man of letters. He had made his debut as a serious critic of literature in a collection of prose essays titled Conversations on Some of the Old Poets (1845), but far more popular was A Fable for Critics (1848), a satiric jeu d'esprit in verse surveying the state of letters in the United States.

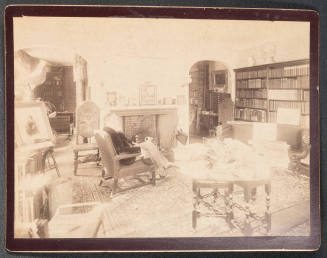

The sale of some land Maria Lowell had inherited allowed the couple to sail in July 1851 to Europe, where they remained fifteen months. In part these travels were to advance Lowell's literary ambitions, but the Lowells also hoped that the mild climate of Rome, where they spent the winter, would benefit Maria Lowell's health, which, never strong, now grew worse. Back in Cambridge in 1852, Lowell continued his studies, worked over some of the impressions gathered during his European trip (later included in Fireside Travels [1864]), and enjoyed the friendships in which his life was extraordinarily rich, relationships maintained over the years by a correspondence not only entertaining but of significant literary merit. Underneath the happy surface, however, was sadness. Three of the four children born to the Lowells between 1845 and 1850 did not survive their second year; only their second daughter lived to maturity. Then in 1853 Maria Lowell died, leaving her husband distraught. Lowell published little during these years; instead, he made his library a place of refuge where he commonly spent twelve to fifteen hours a day at work. The range of his reading was enormous, including the major modern languages as well as the classics, and his mastery of what he read was thorough. He did see through to press popular editions of Dryden, Donne, Marvell, Keats, Wordsworth, and Shelley, and in January 1855 he delivered a series of lectures on the English poets before the Lowell Institute, the influential lyceum association in Boston. His success in these lectures led Harvard to offer Lowell the chair in modern literature that had been Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's, which Lowell accepted on the condition that he first be given a year to study in Germany and Italy. He assumed the post in the autumn of 1856. Lowell's tenure as a Harvard professor coincided with the period of that school's transformation from a small, provincial college to a modern university. Though he was not a principal architect of this great change, Lowell did play an important role in guiding the university in its development during the two decades he spent on the faculty.

Two events in 1857 did much to renew Lowell's outlook: his marriage to Frances Dunlap of Portland, Maine, and his editorship of the Atlantic Monthly, a new monthly that promised to fulfill his early dream of a magazine that, under his guidance, would not compromise in political or artistic matters. Even in the 1840s, when literary nationalism was most intense, Lowell had known that the basis for a great American literature was to be found in neither "sublime spaces" nor "democracy," but rather in economic and social compensation for authors. Now his editorial position would make a difference. Although somewhat wanting in matters of business and editorial routine, he more than compensated in his literary taste and editorial judgment. He was able during the magazine's important early years to maintain that difficult balance between commercial and aesthetic demands, and he did so without sacrificing political responsibility. At his insistence, the Atlantic was one of the first important American periodicals to take a decided stand against slavery; it also engaged in political controversy of other kinds, and under Lowell's stewardship the Atlantic became a leading voice in national debate. Lowell's own political writings began appearing in its pages during his tenure as editor, essays in support of the emerging Republican party and, long before most other New Englanders had measured his greatness, its leader, Abraham Lincoln. Even after his resignation from the Atlantic editorship in 1861, Lowell continued to be one of its most valued writers, especially on political questions during the Civil War. It was then, too, that he again assumed the personae of Hosea Biglow and his down-east friends. The appearance of these new "Biglow Papers" in the Atlantic (1862-1866) met with considerable success, especially verses, such as "Sunthin' in the Pastoral Line," in which Lowell achieves an admirable ironic detachment and lyrical simplicity, a thorough mastery of vernacular art. But, as a book, The Biglow Papers: Second Series (1867) lacks the harmonious design of the first series.

In 1864 Lowell was named coeditor with Charles Eliot Norton of the North American Review, a position he held until 1868. While the actual editorial duties fell mostly on Norton, much of the best writing in the journal was Lowell's, both his political pieces, now supporting a more moderate approach to Reconstruction than that desired by the radical wing of the Republican party, and his literary essays, certainly his greatest achievement during the postwar years. Unburdened by a philosophical system or program, Lowell as a critic possessed a scholar's care for detail and a stylist's delight in expression, and his major essays, such as "Chaucer" (1870), "Spenser" (1875), and "Dante" (1872), remain durable pieces of critical exposition, informed by an appreciation of the literary text in both its historical and linguistic complexities. These, along with many of his other prose pieces, were collected in Among My Books (1870), My Study Windows (1871), and Among My Books: Second Series (1876); not only did they establish beyond question Lowell's reputation as the nation's leading man of letters, but they were also among the most popular of his books, much more so than the poetry he published after the war, The Cathedral, Three Memorial Poems (1877), and Heartsease and Rue (1888).

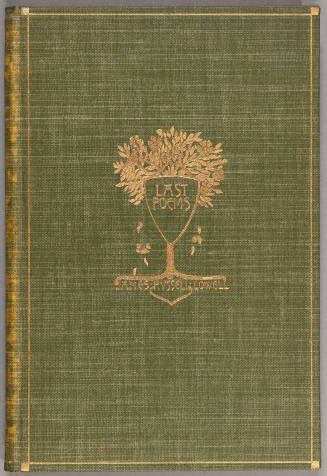

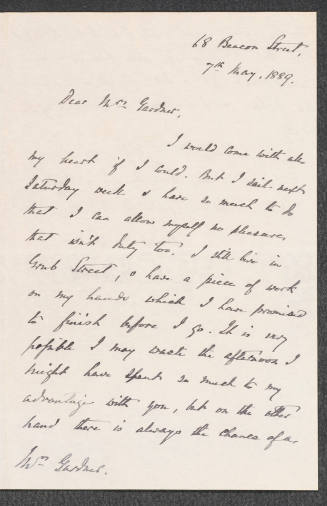

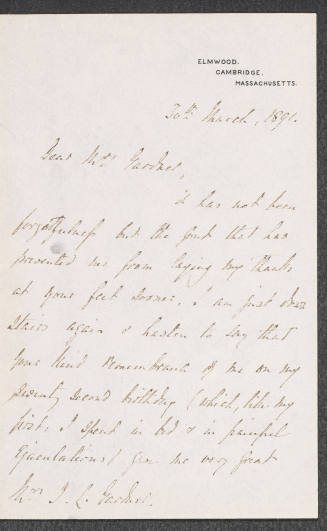

Lowell might have spent the rest of his days reasonably content as a professor of literature at Harvard and a much-sought-after essayist for the leading magazines; at least he did not seem to himself any better off when he took a two-year leave in Europe from 1872 to 1874. His interest in politics continued, though the causes that he now supported, most often in the Nation, were far less noble than those that had motivated him during his youth; now it was the reform of government, especially the civil service, and the recognition in the United States of international copyright. The political verse he published in the Nation, humorous and satirical short pieces, along with his more serious political essays, earned him great respect in the world of affairs, a far more important sphere than literature in the American sense of things. A delegate from Massachusetts to the Republican convention in 1876, he was one of his state's presidential electors later that year. His support for Rutherford B. Hayes in that disputed election undoubtedly contributed to his being appointed U.S. minister to Spain in 1877. Three years later he became U.S. minister at the Court of St. James, a post he held with considerable acclaim until 1885 when, the Democratic party having gained power at home, he was recalled. Alone again following the death of his wife in 1885, Lowell continued as long as his health allowed to spend part of each year in England, where he was in demand as a speaker and a friend, an ambassador of goodwill between the two English-speaking nations, great in the public view, a triumph of style and character. Shortly before his death from cancer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Lowell was able to see into press the ten-volume Riverside Edition of his Writings (1890). Later, Charles Eliot Norton issued several more volumes of essays and poems, Latest Literary Essays and Addresses (1892), The Old English Dramatists (1892), and Last Poems (1895), and he edited the first collection of Lowell's Letters (1894). But by the time Norton came out with the expanded sixteen-volume Elmwood Edition of Lowell's Complete Writings in 1904, literary fashion had lost most of its interest in Lowell, which subsequent years have done nothing to change. But this neglect of Lowell in the twentieth century does not invalidate his importance to his own time; and no understanding of the cultural life of America in the nineteenth century can be complete without recognition of Lowell's centrality and versatility.

Bibliography

The major depository for Lowell's letters and manuscripts is the Houghton Library, Harvard University. Other important collections are at the Library of Congress; the Massachusetts Historical Society; the Pierpont Morgan Library; the Berg Collection, New York Public Library; the University of Texas Library; and the Clifton Waller Barrett Library at the University of Virginia. These materials are the basis of several biographical studies of Lowell, including Martin Duberman, James Russell Lowell (1966), and Leon Howard, Victorian Knight-Errant: A Study of the Early Career of James Russell Lowell (1952). The standard edition of Lowell's Letters was assembled by Charles Eliot Norton (3 vols., 1904). See also M. A. DeWolfe Howe, ed., New Letters (1932). Other printed gatherings of letters, as well as other primary and secondary materials, are listed in Robert A. Rees's bibliographical essay on Lowell in Rees and Earl N. Harbert, eds., Fifteen American Authors before 1900 (1984).

Thomas Wortham

Online Resources

Making of America: Lowell, J. R.

http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/moa/browse.author/l.266.html

Links to digital texts of seventy-six poems and essays by Lowell; part of the Cornell/Michigan Making of America project.

Back to the top

Citation:

Thomas Wortham. "Lowell, James Russell";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01029.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 16:46:04 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.