Lorenzo Monaco

Italian painter, illuminator and draughtsman. His name means Lorenzo the Monk, and he was a member of the Camaldolese Order. His mystical and contemplative works, distinguished by their sinuous line and radiant, high-keyed colour, represent the culmination of the Late Gothic style in Florence. He is remembered principally for his paintings on panel and in illuminated manuscripts, but he also worked to a limited extent in fresco, and a few drawings have also survived. His altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin (1414; Florence, Uffizi), painted for his own monastery, is a virtuoso display of the exquisite craftsmanship and brilliant colour of late medieval art.

1. Life and work.

(i) Before 1414.

He was born Piero di Giovanni but took the name Lorenzo when he entered the Camaldolese Order in the convent of S Maria degli Angeli in Florence. Neither the date nor the place of his birth is known. He is recorded as having taken his simple vows and received minor orders on 10 December 1391; in September 1392 he took solemn vows and was ordained subdeacon. He was ordained deacon in 1396 and, since contemporary practice appears to have been to advance to the diaconate at about the age of 21, this would suggest a birth date in the mid-1370s. His earliest identifiable works of art can be dated to the mid-1390s. The fact that he entered a Florentine convent strongly supports the idea of a Florentine origin, and early documents refer to him as of the ‘popolo di S Michele Bisdomini’, a parish located not far from S Maria degli Angeli. However, Siena has also been proposed as his place of birth, as his sinuous line and delicate colour are stylistically close to the art of contemporary Sienese painters. Moreover, a document of 29 January 1415 refers to him as ‘don Lorenzo dipintore da siene’. Whether or not ‘siene’ (which would be a strange spelling) refers to the city of Siena and why he is not referred to in this way in earlier documents remain questions to plague the biographer.

It is not known where Lorenzo trained. Vasari stated that he was apprenticed to Taddeo Gaddi, but this is impossible, since Taddeo was dead by 1366. However, Lorenzo’s style is akin to that of Taddeo’s youngest son, Agnolo Gaddi, and he may have trained in Agnolo’s shop. It has also been suggested that he was trained as a manuscript illuminator in the scriptorium of S Maria degli Angeli, which was renowned for its illuminated volumes. This latter theory is supported by similarities between his early work and the contemporary works of Don Simone Camaldolese and Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci (1339–90), major manuscript painters who worked for S Maria degli Angeli in the late 1390s.

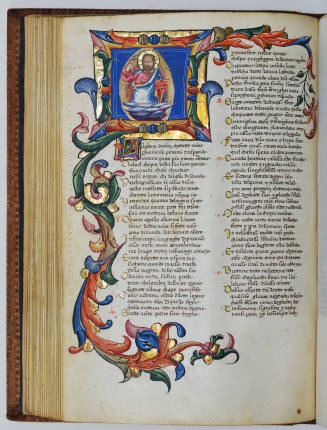

At around the time he was made deacon (1396), Lorenzo seems to have taken up residence outside the convent and established a private workshop, although he continued to follow the religious life. The location of this shop is not known, but he is recorded as operating a shop (perhaps the same one) in the parish of S Bartolo in Corso in early 1402. January 1399 marks his earliest recorded commission, an altarpiece (untraced) executed for the second Ardinghelli Chapel in S Maria del Carmine, Florence. His earliest identifiable works are a group of miniatures representing saints and prophets in initial letters in choir-books in the Biblioteca Medicea–Laurenziana in Florence (MSS Cor. 1, 5 and 8), dated 1396, 1394 and 1395 respectively. The dates inscribed in the volumes cannot be taken as the dates of the illuminations, as they are clearly specified as the dates of the completion of the volumes, that is of the writing, and the decorations may not have been added immediately. Nevertheless, it is relatively safe to assume that these volumes were ornamented in the final years of the 14th century. They reveal a youthful hesitation in the relationship of the figures to their enframing letters and a certain dependence on the work of such older illuminators in the scriptorium as Don Simone and Don Silvestro, a hesitation and dependency not apparent in the illuminations of a choir-book dated 1409 (Florence, Bib. Medicea–Laurenziana, MS. Cor. 3). However, the calligraphic use of line and the delicate colour tones that characterize Lorenzo’s later works are already in evidence. The loss of the Ardinghelli Altarpiece of 1399 is particularly unfortunate, as it would provide a basis for comparing Lorenzo’s work in two media at approximately the same date and would possibly clear up the question of whether he was initially trained as a painter of panels or of manuscripts.

Lorenzo’s large panel of the Agony in the Garden (Florence, Accad. B.A. & Liceo A.) is a dramatic and expressive work that may date from this period. The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Two Angels (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam), a characteristic early work, from the first years of the 15th century, supports the Florentine origin of Lorenzo’s style. The modest scale of the picture suggests a private, devotional function, perhaps as the wing of a diptych. It also places it technically within the realm of miniature painting, although the composition has a monumentality not to be found in most of Lorenzo’s manuscript paintings and small-scale predella panels. The most immediate source of the composition and conception is Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna (Florence, Uffizi). Lorenzo has taken over the poses of the Virgin and Child and has placed them within an architectural setting similar to that used by Giotto. The pointed barrel vault of the throne’s interior clearly establishes the spatial relationship between the two figures and their surroundings. The placement of the attendant angels, who envelop the finials of the arms of the throne with their sleeves and who cross the pierced openings of the structure with their torsos, further establishes a solid, tangible space. This is contrasted with the neutral gold ground with its elaborately tooled border that functions as pure ornament, almost in the way that the decorative edging of a manuscript page might function. At the same time, the colours, the Child’s wrap of deep raspberry-pink fading to almost pure white in the highlights, the Virgin’s steely blue mantle similarly modulated from total saturation to the palest tint, and the touches of vermilion in the cushion of the throne, the wings of the angels and the linings of their metallic blue-white mantles, all point to a dependence on the Orcagna tradition of the second half of the 14th century. At the same time, the softening of faces, both in modelling and in the mood they convey, and the humanizing of attitudes, show a familiarity with Spinello Aretino’s and Agnolo Gaddi’s revival of Giotto’s style in the late 14th century. However, the sinuous lines of the drapery contours and the decorative features, such as the ornamentation of the throne and the delicate, golden feathering of the angels’ wings, are indicative of the Late Gothic style. Lorenzo Monaco’s art is thus in the tradition of late 14th-century Florentine painting, close in time and style to that of such practitioners as Gherardo Starnina and the Master of the Bambino Vispo.

Lorenzo Monaco: Nativity, tempera on wood, gold ground, 8 3/4...Lorenzo’s only surviving documented work is the Monte Oliveto Altarpiece, with the Virgin and Child Enthroned, Attended by SS Bartholomew, John the Baptist, Thaddeus and Benedict (Florence, Accad. B.A. & Liceo A.), which is documented to 1407 and 1411 and bears an inscribed date of 1410. This picture draws on a similarly wide range of stylistic sources. In the same period Lorenzo painted four scenes from the Infancy of Christ (two, London, Courtauld Inst. Gals; one, New York, Met., see fig.; one, Altenburg, Staatl. Lindenau-Mus.) for an untraced altarpiece, and four paintings of Prophets (Abraham, Noah, Moses and David; all New York, Met.) in which the figures are more sculptural and three-dimensional and may date from c. 1408–10.

Among Lorenzo’s paintings on panel, one of the more unusual formats, which he utilized on several occasions, is that of the croce sagomata (cut-out cross), in which the crucified Christ is depicted hanging on the cross as in a Crucifixion scene, but with the cross and figure free-standing. This creates something of an illusion of sculpture. The carved Crucifixes by Donatello and Brunelleschi might indicate the growing popularity of such three-dimensional images in the early 15th century, as distinguished from the painted crosses that enjoyed acclaim in the 13th and 14th centuries. Lorenzo’s works of this kind include the Crucifix (Florence, Accad. B.A. & Liceo A.), a Crucifix in the museum of S Maria delle Vertighe in Monte San Savino, Tuscany, and the dramatic and expressive Crucifix with the Mourning Virgin and St John the Evangelist (Florence, S Giovannino dei Cavalieri), which may be the work described by Vasari as being in the church of the Romiti di Camaldoli (S Salvatore) outside Florence. In this last-named work he added cut-out figures of the Virgin and St John to create a larger tableau. Lorenzo appears to have played a major role in popularizing the croce sagomata form, which survived until the end of the 15th century.

(ii) 1414 and after.

The most ambitious of Lorenzo’s surviving works is the great Coronation of the Virgin (5.12?4.50 m; Florence, Uffizi; see COLOUR, COLOUR PL. II, FIG.). This picture, painted for his own convent of S Maria degli Angeli and dated February 1413 (NS 1414), is his only signed and dated work and shows him at the height of his power. The rather lengthy inscription indicates that he was still following the religious life, though he had been living outside the convent for around 18 years. Although enclosed within a tripartite frame that recalls the triptych format popular in 14th-century altarpieces, the pictorial field is unified into a single space. In the upper centre, in front of a Gothic ciborium from which angels look on, Christ places the crown on the head of his mother, who is dressed in the white of the Camaldolese habit. Crowds of saints, ten on either side (and all male, as befits a convent of men), witness the event. From a pinnacle above the central field a Blessing Redeemer looks down, while the Annunciation is re-enacted in the two pinnacles over the side compartments. Ten prophets grace the pilasters of the frame, and a predella of six laterally elongated quatrefoils offers four stories from the Legend of St Benedict flanking the Nativity and the Adoration of the Magi.

The great courtly ritual represented on the principal field has its roots in Florentine tradition, going back to the Baroncelli Altarpiece (c. 1330; Florence, Santa Croce) from Giotto’s workshop and developed by numerous followers of Giotto in the second half of the 14th century. The graceful sway of the bodies arrayed in syncopated ranks plays against the sinuous rhythms of their drapery. The delicate colours—perhaps appearing more pastel-toned than intended, due to a 19th-century cleaning with soda—are a perfect complement to these linear rhythms, setting off the folds under a veil of almost translucent tonalities. Thus a balance is achieved between the three-dimensional elements of illusionism and the decorative qualities of pure surface pattern. The predella panels create a similar fusion of decorative line and colour with functional space and drama. The awkward frame of the quatrefoil shape is made to harmonize with the architectural and compositional elements within the paintings, so that a chevron pattern links the six subjects together horizontally, while at the same time they function individually as dramatic narratives within a functional, if abbreviated, space.

Lorenzo and his shop used the S Maria degli Angeli (Uffizi) Coronation as a model for another major Camaldolese commission, probably very shortly thereafter. Originally painted for the monastery of S Benedetto fuori della Porta a Pinti, outside Florence, and seen by Vasari in S Maria degli Angeli (where it was placed after the destruction of S Benedetto), this is surely the Coronation of the Virgin of which the major panels are now in the National Gallery, London. (For the history and reconstruction of this work, see Eisenberg, pp. 138–45.) Of generally inferior quality compared with its prototype, it demonstrates the popularity of Lorenzo’s style with a segment of the artistic public, and the way in which that style was treated by his immediate following.

The Annunciation with SS Catherine of Alexandria, Anthony Abbot, Proculus and Francis of Assisi (c. 1418; Florence, Accad. B.A. & Liceo A.) develops Lorenzo’s use of complex rhythms and lyrically graceful figures. The Adoration of the Magi (Florence, Uffizi), of uncertain provenance, dates from the early 1420s and is distinguished by the aristocratic elegance and exoticism of the figures. An altarpiece of the Deposition (Florence, Mus. S Marco) was commissioned by Palla Strozzi for the sacristy of Santa Trìnita, Florence. Begun by Lorenzo Monaco, probably c. 1420–22, it was finished by Fra Angelico. The painted frame by Lorenzo survives; the three pinnacle panels, with the Resurrection, a Noli me tangere and the Holy Women at the Tomb, remain with the altarpiece, while three small panels intended as predella scenes, the Nativity, the Legend of St Onuphrius and St Nicholas Calming the Storm (Florence, Accad. B.A. & Liceo A.), are now separate.

In this late period, probably after 1420, Lorenzo undertook the decoration of the Bartolini Salimbeni Chapel in Santa Trìnita, Florence, his first and only known attempt at fresco painting. The programme, probably the most complex he ever undertook, consisted of eight scenes from the Life and Legends of the Virgin on the walls, Four Prophets on the vault and Four Saints on the soffits of the entrance arch (all in situ). The scheme was completed with the addition of an altarpiece of the Annunciation , with a predella of four scenes, the Visitation, the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi and the Flight into Egypt (all in situ). The frescoed scenes were all taken from the apocryphal literature, while those that make up the altarpiece were all scriptural. On the axis of the chapel, the Assumption of the Virgin on the exterior wall above the entrance aligns with the Miracle of the Snow in the lunette of the back wall, which in turn is situated directly above the Annunciation in the altarpiece. It is known that two feast days were singled out for special celebration in this chapel, the Feast of the Annunciation on 25 March and an unspecified feast in August. The Miracle of the Snow was commemorated on 5 August and the Assumption of the Virgin on 15 August. Perhaps the otherwise unspecified August celebration combined and commemorated both of these events. The entire complex was undoubtedly arranged to suit the needs of particular Marian devotions associated with the chapel and its donors.

In devising the eight scenes from the Marian legend, Lorenzo depended on the numerous cycles existing in and around Florence, in particular those of the Gaddi family workshop. He once again demonstrated his reliance on Florentine traditions and, in particular, on the tradition initiated by Giotto. The altarpiece of the Annunciation, however, suggests that Lorenzo had encountered the new naturalism of the 1420s. Its iconography depends on a Sienese, rather than a Florentine tradition, but an attempt has been made to depict the architectural setting more convincingly, on a scale somewhat in accord with that of its occupants. The space is complex, with room opening on room, revealing a labyrinth of spaces. Nevertheless, it retains the insubstantiality of Lorenzo’s earlier structures, which served more as backdrops to set the scene than as actual, inhabitable spaces. The figures, too, have become more voluminous, wrapped in fabric heavier than that of the figures in the Uffizi Coronation, but at the same time retaining all of their courtly elegance. As the angel Gabriel alights to deliver his greeting to Mary, he does not rest on the patterned floor so much as hover in front of it. The inverted perspective of the floor patterning might appear to encourage this perception on the main panel, but in the Visitation panel of the predella, Elizabeth similarly seems to float in front of the unarticulated ground rather than to rest on it; and in the Nativity of the predella Joseph, sitting on the ground at the lower right, appears to hover on his elegantly outspread mantle like some mystic levitating on a magic carpet. The colour scheme has altered, with greater use of more sombre, earthy colours, especially in the grounds, to set off the increasingly complex arrangements of softer, more delicate colours in the figures.

Lorenzo Monaco’s death, like his birth, is not recorded. In the 14th and 15th centuries religious houses kept their own death records, separate from the secular libri dei morti kept by the Comune, but such records for S Maria degli Angeli have not survived. A marginal notation in another document from the convent indicates that he died on 24 May, but the year is not specified. A contract for an altarpiece dated 3 March 1421 (NS 1422) indicates that he was still living at that time. Vasari stated that he died at the age of 55, but gave no indication of the year. If his age is given correctly and the supposition of his birth date in the middle years of the 1370s is also correct, he would then have died sometime in the middle to late 1420s. This date would be consistent with the style of the works judged to be his latest, which demonstrate a growing sense of naturalism, commensurate with the developments in the art of Masaccio and Fra Angelico in the 1420s.

2. Working methods and technique.

Most of Lorenzo Monaco’s works are in tempera on panel; he was supremely gifted as a colourist, and his sharp greens and yellows, bright pinks and blues are softly modelled and orchestrated contrapuntally; his craftsmanship in gold was exquisitely refined, and each of the haloes in the vast Coronation of the Virgin bears a different design. He prepared his pictures with drawings, some of which have survived; a drawing of Six Kneeling Saints (Florence, Uffizi) is a preparatory study for a group in either the Uffizi or the London Coronation of the Virgin. An unusual pair of drawings, the Visitation and the Journey of the Magi (both Berlin, Kupferstichkab.), in pen and brush with brown ink, coloured washes and tempera on parchment, fall somewhere between manuscript illuminations, presentation drawings and working drawings. A somewhat rare example of verre églomisé painting depicting the Virgin of Humility with SS John the Baptist and John the Evangelist (Turin, Mus. Civ. A. Ant.), although executed primarily by Lorenzo’s shop, represents another graphic medium that Lorenzo explored.

Technical elements in the execution of the frescoes in the Bartolini Salimbeni Chapel in Santa Trìnita, such as the irregularity of the giornate, which do not always coincide with complete figures and which occasionally cut through haloes and other elements, indicate his lack of familiarity with the medium. The blue background, painted a secco, has vanished. Detailed drawings must have existed for these frescoes. The sinopie that have been uncovered are very brief and sketchy, indicating that the compositions must have been worked out extensively on paper. The chapel was whitewashed in the early 18th century, and the paintings were unknown until 1887, when they were cleaned and restored by Augusto Burchi. A restoration in 1961–2 undid some of the damage done by Burchi’s attempt to re-create the original condition of the paintings, but the paintings are in very poor condition. In places the intonaco has entirely fallen away, revealing the underlying sinopie.

Lorenzo directed a large workshop, and the inscription on the Uffizi Coronation of the Virgin emphasizes that it was a collaborative work. The extensive collaboration of the workshop, even in smaller works, has been discussed by Eisenberg, who has stressed that this shop produced many devotional images, such as the Virgin and Child Enthroned (c. 1418; Edinburgh, N.G.), for which Lorenzo supplied only the design.

3. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

Early sources, other than the scant documentation about his life and work in S Maria degli Angeli, reveal little about Lorenzo Monaco. He is not mentioned at all by Ghiberti in his autobiographical I Commentarii (written c. 1447–55), even though the stylistic affinity of the two artists would suggest that they represent the sculptural and painterly incarnations of the same spirit. Albertinelli (1510) said very little; Il libro di Antonio Billi (written c. 1516–30) and the manuscript by the Anonimo Magliabechiano (written c. 1537–42) pay him sparse attention, mentioning only a handful of works (mostly untraced). Vasari devoted a Vita to him but, apart from praising his virtue and listing a small number of his most important works (mostly untraced), he provides little concrete information, filling much of the chapter with an estimation of the contemplative life and of other monk painters from S Maria degli Angeli. However, the minimal information provided by Vasari remained virtually the sole source of Lorenzo Monaco’s biography and critical assessment until the latter part of the 19th century.

Modern critical assessment of Lorenzo Monaco’s style began with Carlo Pini and Gaetano Milanesi in the mid-19th century. A.-F. Rio, in 1861, lumped Lorenzo together with Gentile da Fabriano and Fra Angelico as manifestations of a ‘mystical school’ of Florentine painters. It was J. A. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle, in 1864, who set the appreciation of Lorenzo’s work on a new path. Proposing him as one of the legitimate heirs of Giotto, they found in his work a depth and feeling akin to that of the earlier master, such that they recognized and identified as his paintings some that were then attributed to Giotto himself, to Taddeo Gaddi and to other 14th-century painters. Crowe and Cavalcaselle began the reconstitution of his oeuvre that culminated in the Lists of Bernard Berenson that first appeared in 1909. At the start of the 20th century Roger Fry recognized the quality of Lorenzo’s work; but Osvald Sirén wrote the first complete monograph on the artist in 1905.

Lorenzo Monaco does not seem to have been highly regarded in the years following his death. His style was not widely imitated. Only a handful of artists followed immediately in his footsteps, though none of them ranked in the first order of 15th-century Florentine painters, and they were mostly of an archaicizing temperament. Although Lorenzo was apparently esteemed in his lifetime, especially by his brethren in S Maria degli Angeli, his work fell from favour not long after, and even his great Coronation altarpiece for the convent was replaced in the 16th century with a painting by Alessandro Allori, Lorenzo’s work being relegated to the provincial convent of the Order at Cerretto. Many of his works hung in museums with attributions to better-known artists until the ‘rediscovery’ of Lorenzo in the late 19th century and in the 20th.

Bibliography

F. Albertinelli: Memorie di molte statue et picture sono nella inclyta ciptà di Florencia ... (Florence, 1510/R Letchworth, 1909) ( OPENURL )

A. Billi: ‘Il libro di Antonio Billi’ (MS. c. 1516–30; Florence, Bib. N.); ed. C. von Fabriczy, Archv. Stor. It., ser. 5, vii (1891), pp. 299–368 ( OPENURL )

Anonimo Gaddiano [Magliabechiano]: ‘Il codice dell’Anonimo Gaddiano nella Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze’ (MS. c. 1537–42; Florence, Bib. N.); ed. C. von Fabriczy, Archv. Stor. It., ser. 5, xii (1893), pp. 15–94, 275–334 ( OPENURL )

G. Vasari: Vite (1550; rev. 2/1568); ed. G. Milanesi (1878–85), ii, pp. 17–32 ( OPENURL )

A.-F. Rio: De l’art chrétien, i (Paris, 1836, 2/1861–7) ( OPENURL )

J. A. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle: A New History of Painting in Italy (London, 1864), i, pp. 551–8 ( OPENURL )

R. E. Fry: ‘Florentine Painting of the Fourteenth Century’, Mnthly Rev., iii (1901), pp. 112–34 ( OPENURL )

R. E. Fry: ‘Pictures in the Collection of Sir Hubert Parry at Highnam Court, near Gloucester: I’, Burl. Mag., ii (1903), pp. 117–31 ( OPENURL )

O. Sirén: Don Lorenzo Monaco (Strasbourg, 1905) ( OPENURL )

R. van Marle: Italian Schools (1923–38), ix, pp. 115–69 ( OPENURL )

M. Meiss: ‘Four Panels by Lorenzo Monaco’, Burl. Mag., c (1958), pp. 191–8 ( OPENURL )

E. Borsook: The Mural Painters of Tuscany: From Cimabue to Andrea del Sarto (London, 1960, rev. Oxford, 1980) ( OPENURL )

B. Berenson: Florentine School (1963) ( OPENURL )

G. P. de Montebello: ‘Four Prophets by Lorenzo Monaco’, Bull. Met., xxv/4 (1966), pp. 155–68 ( OPENURL )

C. Gardner von Teuffel: ‘Lorenzo Monaco, Filippo Lippi und Filippo Brunelleschi: Die Erfindung der Renaissancepala’, Z. Kstgesch., xlv (1982), pp. 1–30 ( OPENURL )

M. Eisenberg: Lorenzo Monaco (Princeton, 1989) [complete cat. and bibliog.] ( OPENURL )

D. Gordon: ‘The Altarpiece by Lorenzo Monaco in the National Gallery, London’, Burl. Mag., cxxxvii/1112 (1995), pp. 723–7 ( OPENURL )

James Czarnecki

Italian painter, illuminator and draughtsman. His name means Lorenzo the Monk, and he was a member of the Camaldolese Order. His mystical and contemplative works, distinguished by their sinuous line and radiant, high-keyed colour, represent the culmination of the Late Gothic style in Florence. He is remembered principally for his paintings on panel and in illuminated manuscripts, but he also worked to a limited extent in fresco, and a few drawings have also survived. His altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin (1414; Florence, Uffizi), painted for his own monastery, is a virtuoso display of the exquisite craftsmanship and brilliant colour of late medieval art.

1. Life and work.

(i) Before 1414.

He was born Piero di Giovanni but took the name Lorenzo when he entered the Camaldolese Order in the convent of S Maria degli Angeli in Florence. Neither the date nor the place of his birth is known. He is recorded as having taken his simple vows and received minor orders on 10 December 1391; in September 1392 he took solemn vows and was ordained subdeacon. He was ordained deacon in 1396 and, since contemporary practice appears to have been to advance to the diaconate at about the age of 21, this would suggest a birth date in the mid-1370s. His earliest identifiable works of art can be dated to the mid-1390s. The fact that he entered a Florentine convent strongly supports the idea of a Florentine origin, and early documents refer to him as of the ‘popolo di S Michele Bisdomini’, a parish located not far from S Maria degli Angeli. However, Siena has also been proposed as his place of birth, as his sinuous line and delicate colour are stylistically close to the art of contemporary Sienese painters. Moreover, a document of 29 January 1415 refers to him as ‘don Lorenzo dipintore da siene’. Whether or not ‘siene’ (which would be a strange spelling) refers to the city of Siena and why he is not referred to in this way in earlier documents remain questions to plague the biographer.

It is not known where Lorenzo trained. Vasari stated that he was apprenticed to Taddeo Gaddi, but this is impossible, since Taddeo was dead by 1366. However, Lorenzo’s style is akin to that of Taddeo’s youngest son, Agnolo Gaddi, and he may have trained in Agnolo’s shop. It has also been suggested that he was trained as a manuscript illuminator in the scriptorium of S Maria degli Angeli, which was renowned for its illuminated volumes. This latter theory is supported by similarities between his early work and the contemporary works of Don Simone Camaldolese and Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci (1339–90), major manuscript painters who worked for S Maria degli Angeli in the late 1390s.

At around the time he was made deacon (1396), Lorenzo seems to have taken up residence outside the convent and established a private workshop, although he continued to follow the religious life. The location of this shop is not known, but he is recorded as operating a shop (perhaps the same one) in the parish of S Bartolo in Corso in early 1402. January 1399 marks his earliest recorded commission, an altarpiece (untraced) executed for the second Ardinghelli Chapel in S Maria del Carmine, Florence. His earliest identifiable works are a group of miniatures representing saints and prophets in initial letters in choir-books in the Biblioteca Medicea–Laurenziana in Florence (MSS Cor. 1, 5 and 8), dated 1396, 1394 and 1395 respectively. The dates inscribed in the volumes cannot be taken as the dates of the illuminations, as they are clearly specified as the dates of the completion of the volumes, that is of the writing, and the decorations may not have been added immediately. Nevertheless, it is relatively safe to assume that these volumes were ornamented in the final years of the 14th century. They reveal a youthful hesitation in the relationship of the figures to their enframing letters and a certain dependence on the work of such older illuminators in the scriptorium as Don Simone and Don Silvestro, a hesitation and dependency not apparent in the illuminations of a choir-book dated 1409 (Florence, Bib. Medicea–Laurenziana, MS. Cor. 3). However, the calligraphic use of line and the delicate colour tones that characterize Lorenzo’s later works are already in evidence. The loss of the Ardinghelli Altarpiece of 1399 is particularly unfortunate, as it would provide a basis for comparing Lorenzo’s work in two media at approximately the same date and would possibly clear up the question of whether he was initially trained as a painter of panels or of manuscripts.

Lorenzo’s large panel of the Agony in the Garden (Florence, Accad. B.A. & Liceo A.) is a dramatic and expressive work that may date from this period. The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Two Angels (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam), a characteristic early work, from the first years of the 15th century, supports the Florentine origin of Lorenzo’s style. The modest scale of the picture suggests a private, devotional function, perhaps as the wing of a diptych. It also places it technically within the realm of miniature painting, although the composition has a monumentality not to be found in most of Lorenzo’s manuscript paintings and small-scale predella panels. The most immediate source of the composition and conception is Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna (Florence, Uffizi). Lorenzo has taken over the poses of the Virgin and Child and has placed them within an architectural setting similar to that used by Giotto. The pointed barrel vault of the throne’s interior clearly establishes the spatial relationship between the two figures and their surroundings. The placement of the attendant angels, who envelop the finials of the arms of the throne with their sleeves and who cross the pierced openings of the structure with their torsos, further establishes a solid, tangible space. This is contrasted with the neutral gold ground with its elaborately tooled border that functions as pure ornament, almost in the way that the decorative edging of a manuscript page might function. At the same time, the colours, the Child’s wrap of deep raspberry-pink fading to almost pure white in the highlights, the Virgin’s steely blue mantle similarly modulated from total saturation to the palest tint, and the touches of vermilion in the cushion of the throne, the wings of the angels and the linings of their metallic blue-white mantles, all point to a dependence on the Orcagna tradition of the second half of the 14th century. At the same time, the softening of faces, both in modelling and in the mood they convey, and the humanizing of attitudes, show a familiarity with Spinello Aretino’s and Agnolo Gaddi’s revival of Giotto’s style in the late 14th century. However, t