Bonham Norton

Norton, Bonham (1565–1635), printer and bookseller, was born in Onibury, Shropshire, the only son of William Norton (1526/7–1593), printer and bookseller, and his wife, Joan (d. in or after 1593), daughter of William Bonham (1497–1557), printer and bookseller. On 15 December 1590 he married Jane (c.1566–1640), daughter of Sir Thomas Owen of Condover, Shropshire, with whom he had nine sons and four daughters. Upon his father's death in 1593, Norton received the bulk of the estate, which included not only a significant amount of money but also large landholdings in Shropshire, Middlesex, and Kent. His wealth and connections quickly allowed him to become one of the most important and powerful stationers of the period. Freed by patrimony of the Stationers' Company on 4 February 1594, he was chosen into the livery five months later, elected as an assistant on 6 June 1597, and served as master of the company for 1613, 1626, and 1629. He served briefly as an alderman for Aldgate in London in 1607, was elected sheriff of Shropshire in 1611, received a grant of arms in 1612, and was elected a governor of Christ's Hospital in 1613. He also developed his property holdings in the Shropshire town of Church Stretton. He helped with the rebuilding of the town after a fire in 1593, providing a school and a court house as well as a large town house for himself, known as The Hall. By 1616 he held nine or ten copyholds in the manor (probably along with the local demesne wood of Bushmoor) and in that year, as ‘lord of the larger part of the lands and possessions’ in the town, he was granted the right to hold a Thursday market (VCH Shropshire, 10.93).

For most of his publishing career Norton dealt with privileged works, classes of valuable texts protected as monopolies by royal letters of patent. Between 1597 and 1599 he was a partner in the law book patent with Thomas Wight, who had acquired the privilege upon the death of its previous holder, Charles Yetsweirt. During that time they printed such profitable works as William West's general treatise on English law, Of Symboleography, and Sir Anthony Fitzherbert's La nouvelle natura brevium, a manual of legal procedure. In 1605 Norton and his cousin John Norton, along with fellow stationer and Shropshire native John Bill, established the Officina Nortoniana, a house that dealt primarily in scholarly books printed in London and on the continent. Two years earlier John had succeeded in wresting away the patent for Latin, Greek, and Hebrew printing from John Battersby, and the privileged titles that went with the office also became part of the Nortoniana business. Holding onto the right to print those titles, however, proved difficult. Both Battersby and his assignees brought court actions in an attempt to regain control over publishing rights, and in the middle of the fray Robert Barker, who held the office of king's printer, managed to acquire the reversion for John Norton's patent. It was not until 1606 that a working compromise agreeable to all parties was reached.

When John Norton died in 1612, Bonham Norton was named principal heir and executor of his cousin's estate. He immediately brought suit in the court of exchequer, asserting that the previous agreements were now void and claiming the sole right to exercise the privilege. Although the suit was denied, in January 1613 he obtained the royal patent for Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, to take effect when the existing patent expired. Further court actions followed, and it was not until Battersby's death in 1618 that he gained clear control over the materials. He then turned around in late 1619 and sold the patent to the Stationers' Company, who folded it into the newly formed Latin stock. Unfortunately the Latin stock venture proved unsuccessful, and Norton bought back the patent in 1624, holding it until his death.

Norton was an aggressive businessman, frequently using the law and company courts in an attempt to gain an advantage over his fellow stationers. Perhaps the most important series of the legal fights that Norton pursued concerned the important office of king's printer. For a number of years Norton had dealings with Robert Barker, and at some point he and John Bill apparently became partners with Barker in the king's printing office, perhaps as part of an investment arrangement to pay for the so-called Authorized Version of the Bible in 1611. Early in the partnership things went smoothly, so smoothly in fact that Barker's eldest son, Christopher, and Norton's eldest daughter, Sarah, were married in 1615. As was so often the case with Norton, the arrangement turned sour, and the constantly changing imprint formulae on books printed by the office from 1617 to 1629 bear witness to the legal imbroglio that followed.

Barker began the exchange in 1618 by filing suit in the court of chancery to evict Norton and Bill from the business. Barker claimed that he had placed his son Christopher in the establishment with the understanding that Norton and Bill would ‘ayde and direct [Christopher] for his best advantage in the execution of the said office of printinge’ (Plomer, ‘King's printing house’, 356). Earlier in the decade Barker, tired of the squabbles and deeply in debt, had determined to sell the patent. Norton and Bill set their sights on this prize, and according to Barker's statement, they ‘did cunningly devise & practise how to obteyne & get the said office of printing wholly into their own hands’ (ibid., 357), even using Christopher against his father. A complicated sales agreement ensued, one that included a clause whereby Barker had the option after a year and a day to buy back the operation. Barker claimed that all the sales documents were destroyed in a fire shortly after the deal was signed, and that Norton and Bill had subsequently refused to turn over the office or to render an account of the business. Norton responded in his own statement to the court that he and Bill had reluctantly bought the patent only after it had become clear that there were no other potential buyers, that the option to buy back the business claimed by Barker had never been part of the deal, and that he was in no way bound to give an account of the office.

On 7 May 1619 the court found for Barker, holding that the transaction had not been a sale but only security for a loan. Norton was ordered to surrender the office, although Bill's right to the office was upheld and he continued to operate the establishment along with Barker. The court also ordered Barker to repay Norton his initial investment, which he apparently failed to do, for some time in 1620 Norton reoccupied the office. Again Barker sued, and for the rest of the decade he attempted to regain the patent while Norton employed all manner of evasions and subterfuges. Finally, on 20 October 1629, the court of chancery settled the matter, awarding the office of king's printer to Barker and Bill. Norton's response was unwise. His agents broke into the office immediately after the decree and carried off stock and equipment. Norton refused to divulge the whereabouts of one of the agents (his son Roger) and was imprisoned. He also publicly accused the lord keeper of taking a bribe to decide in Barker's favour. After a trial in Star Chamber in July 1630, Norton was fined £6000 and again imprisoned ‘during his majesties pleasure’ (Plomer, ‘King's printing house’, 366). Whether at this point Norton remained in prison or retired to his family home in Shropshire is unclear. Perhaps signalling his withdrawal from the trade, in 1632 the rights to a number of popular titles were transferred to Joyce Norton, the widow of his cousin John, and her partner Richard Whitaker.

Norton died intestate on 5 April 1635, and the administration of his estate was granted to his son John, a lawyer, on 28 May 1636. He was buried in St Faith's under St Paul's, under the choir of St Paul's Cathedral in London, where his widow erected a monument next to those of his father and three of his sons.

David L. Gants

Sources H. R. Plomer, ‘The king's printing house under the Stuarts’, The Library, new ser., 2 (1901), 353–75 · W. A. Jackson, ed., Records of the court of the Stationers' Company, 1602 to 1640 (1957) · STC, 1475–1640 · H. G. Aldis and others, A dictionary of printers and booksellers in England, Scotland and Ireland, and of foreign printers of English books, 1557–1640, ed. R. B. McKerrow (1910) · N. Mace, ‘The history of the grammar patent, 1547–1620’, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 87 (1993), 419–36 · H. R. Plomer, Wills of English printers and stationers (1903) · Arber, Regs. Stationers · E. G. Duff, A century of the English book trade (1905) · W. Dugdale, The history of St Paul’s Cathedral in London (1658) · VCH Shropshire, 10.76, 79, 85, 92–4, 101, 108, 115, 118 · A. Hunt, ‘Book trade patents, 1603–1640’, The book trade and its customers, 1450–1900: historical essays for Robin Myers, ed. A. Hunt, G. Mandelbrote, and A. Shell (1997), 27–54

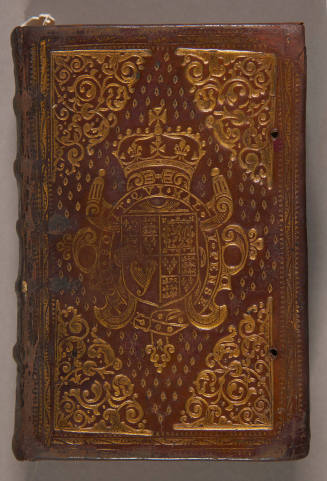

Archives BL, drawing of arms granted February 1612, Harley MS 6095, fol. 17v · BL, drawing of arms, Harley MS 6140, fol. 40r

© Oxford University Press 2004–14

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

David L. Gants, ‘Norton, Bonham (1565–1635)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/20338, accessed 27 Jan 2014]