Thomas Jefferson Coolidge

found: The Thomas Jefferson papers [MI] 1977: t.p. (Thomas Jefferson Coolidge) intro (great-grandson of Thomas Jefferson)

found: Who was who in America, v. 1, 1897-1942 (Coolidge, T(homas) Jefferson, b. 1831, d. 1920)

Coolidge, Thomas Jefferson (26 Aug. 1831-17 Nov. 1920), businessman and diplomat, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Joseph Coolidge, Jr., a businessman, and Eleanora Wayles Randolph. On his father's side Coolidge was descended from John Coolidge, one of the first settlers of Watertown; on his mother's side he was descended from Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States. His parents were members of the Boston elite, and throughout his life Coolidge moved in the same circles.

Much of Coolidge's early education took place in Europe, as his parents made frequent trips abroad. He attended a boarding school in England, spent five years at a boarding school outside Geneva, Switzerland, while his parents were in China on business, and finished off his secondary education at a Gymnasium in Dresden, Germany. These years were to enrich his diplomatic skills, for he became fluent in French and German.

In 1847 Coolidge returned to the United States and entered Harvard as a sophomore. His rigorous secondary education in Europe and his quickness of mind gave him advantages over his classmates, and he relied on these advantages to carry him through. He described himself as "lazy" while at Harvard, but he nevertheless graduated seventeenth in a class of more than fifty in 1850. In 1853 he was awarded an M.A., and in 1902 Harvard conferred on him an honorary LL.D. Despite his belief that Harvard did not greatly stir him as an undergraduate, Coolidge remained devoted to the university throughout his life. He served on the Harvard Board of Overseers from 1886 to 1897. He donated to Harvard the funds to construct the Jefferson Physical Laboratory, completed in 1884, as well as funds to promote research in the sciences. He also gave the university the resources to construct a small laboratory for chemical research as a memorial to his son, a member of the class of 1884.

Upon completing his education, Coolidge determined that his main responsibility was to make money, and he began a career in business. In 1852, however, his life took a momentous turn. He married Hetty Sullivan Appleton, daughter of William Appleton, who, together with Abbott Lawrence and Nathan Appleton, was largely responsible for creating the Massachusetts textile industry. In 1857 Coolidge's father-in-law prevailed on Coolidge to give up an independent business career and take on a salaried position in one of Appleton's textile firms. In the position of treasurer of the Boott Mills, Coolidge resuscitated the finances of the mills and gained a permanent reputation as a skilled manager of textile operations.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, Coolidge took advantage of the return of peace to give up active participation in business and take his entire family to Europe for three years, hoping thereby to restore his wife's health. When he returned in 1868, he was immediately enlisted by the Boston textile magnates as treasurer of the Lawrence Manufacturing Company. Eight years later he reached the pinnacle of the New England textile world when he became treasurer of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, one of the nation's largest textile manufacturing complexes. By custom, the treasurer was the officer most intimately involved in actual operations. Coolidge's financial management of the firm from 1876 to 1898 secured its future.

Coolidge used his now considerable fortune to participate in the great railroad expansion that marked the last quarter of the nineteenth century. In 1876 he joined the board of directors of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad and continued to play an important part in the railroad's affairs for many years as a major investor. He was briefly prevailed upon to accept the presidency of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, but he resigned the presidency in 1881, after just eighteen months in office.

In the 1880s Coolidge was principally responsible for the reconstitution of the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company, driven into bankruptcy by the speculations of Henry Villard. In 1887 he briefly assumed the presidency of the Boston and Lowell Railway long enough to arrange for its absorption into the Boston and Maine. In the mid-1890s he was one of a group of investors who engineered the reorganization of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Coolidge was also involved in the Boston banking business. He joined the board of directors of the Merchants Bank in 1876 and subsequently served on the boards of the New England Trust Company and the Bay State Trust Company. His chief participation in banking, however, occurred when he and his son jointly founded the Old Colony Trust Company in 1890. His son T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., became the president of the bank.

Notwithstanding his remarkable business acumen, Coolidge himself rated his various public roles as much more important. The first major public position he occupied was as a member of the Boston Parks Commission in 1875-1876. With the advice of Frederick Law Olmsted, the commission laid out the substantial system of parkways that threads through Boston. In 1889 Coolidge was appointed a representative of the United States to the Pan-American Congress, designed to build ties among the various countries of North and South America. At the congress, he defended the gold standard against the prosilver advocacy of nearly all the other participants. In his report he expressed his strong opposition to the proposal of an "international" silver dollar that would circulate freely in all the Americas.

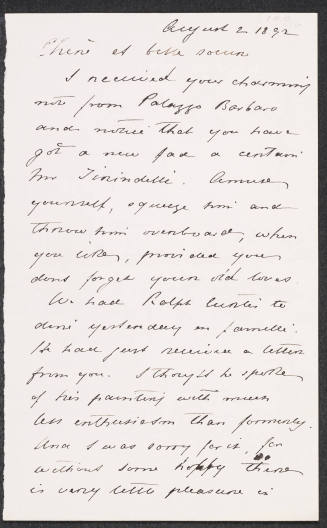

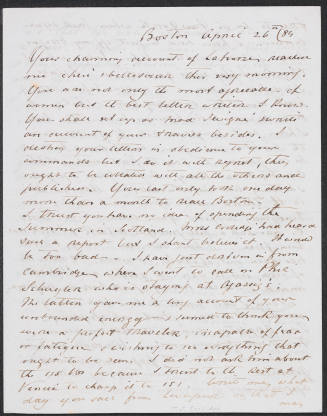

Coolidge himself believed that the peak of his career was reached when he was appointed the American minister to France in 1892. It was a post for which he was ideally suited. His private fortune enabled him to finance the entertaining that was a necessary part of the duties of a diplomatic representative, and his fluency in French and German enabled him to deal effectively with the French government and with the other members of the diplomatic corps stationed in Paris. His tenure in the post lasted less than a year, because in March 1893 the new president, Grover Cleveland, named a Democrat as the new ambassador. It was, however, Coolidge who had persuaded the U.S. government to raise the rank of its representative in Paris. Nevertheless, Coolidge described his year in Paris as "the happiest year of my life."

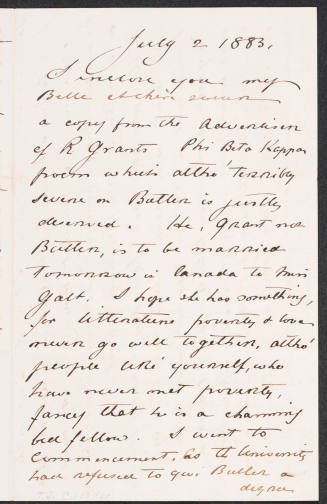

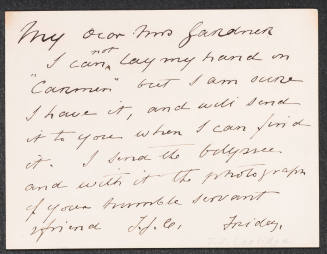

In 1900 Coolidge assessed his own life in a brief autobiography that he had privately printed in 1902. The forty-eight copies were distributed among his friends and associates. It was subsequently--after his death and with the permission of his family--printed by Houghton and Mifflin as T. Jefferson Coolidge, 1831-1920: An Autobiography and copyrighted by the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1923. In the autobiography Coolidge deliberately excludes nearly all material dealing with his business career. In Who's Who in America he described himself as a "diplomat," not as a businessman, and his autobiography deals mainly with his numerous travels and his experiences while serving as American minister to France. The autobiography is organized somewhat like a diary and evidently was based on diary notes kept by Coolidge. It is filled with accounts of travels all over America, the Caribbean, Europe, and down the Nile. The Coolidges appear to have been inveterate sightseers. It also makes clear that they had instant entrée to the elites of all the industrialized countries.

After the turn of the century, Coolidge gradually withdrew from active involvement in public or business affairs. He grew increasingly deaf, but his zest for participation was destroyed only when his son died in 1912. His wife had died in 1901, and another of his four children also preceded him in death. He remained physically vigorous until the day of his death in Boston.

Although Coolidge set greater store by his various public roles, the primary encomium passed on his life in the eulogy delivered to the Massachusetts Historical Society was that, in a time subsequently dubbed the era of the robber barons, Coolidge "was always and wholly without reproach . . . [for he] preferred . . . to carry down-town with him the honorable spirit of a gentleman for daily use in rooms where it did not habitually intrude."

Bibliography

The records of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company are preserved in the Manchester (N.H.) Historic Association. The association compiled a record of its Amoskeag holdings, Guide to the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company Records (1985). Three volumes of treasurer's reports for the years 1865-1922 cover Coolidge's years as treasurer. In addition, a cubic foot of treasurer's files, including correspondence, legal documents, and the like, for the years 1835-1915 includes Coolidge's operations. Coolidge's report to the Pan-American Congress in 1889 is printed as an appendix to the published version of his autobiography. A few details of Coolidge's business career are in Arthur M. Johnson and Barry E. Supple, Boston Capitalists and Western Railroads (1967), and Julius Grodinsky, Transcontinental Railway Strategy, 1869-1893: A Study of Businessmen (1967). The customary eulogy delivered to the Massachusetts Historical Society by John T. Morse, Jr., is printed in its Proceedings 54 (Jan. 1921): 141-49. It contains a number of details omitted from his autobiography and gives a measured assessment of Coolidge's contributions. An obituary is in the Boston Globe, 18 Nov. 1920.

Nancy Gordon,

Citation:

Nancy Gordon, . "Coolidge, Thomas Jefferson";

http://www.anb.org/articles/10/10-00326.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:07:47 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.