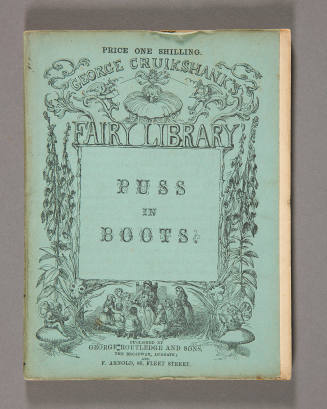

George Cruikshank

LC name authority rec. n80067117

LC headin: Cruikshank, George, 1792-1878

Biography:

Cruikshank, George (1792–1878), graphic artist, was born on 27 September 1792, and baptized on 6 November at St George's, Bloomsbury Way, London, the second son of Isaac Cruikshank (1764–1811), caricaturist, and his wife, Mary, née MacNaughton (1769–1853). At the time the family lived at 27 Duke Street; by 1808 they had removed to 117 Dorset Street, Salisbury Square. In that four-storey terrace house George, ‘cradled in caricature’ as he later put it (Jerrold, 1.72), and his elder brother, (Isaac) Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856), often watched their father prepare drawings and etchings in his attic studio. Their younger sister Margaret Eliza, born on 29 August 1807, also inherited the family proclivity for drawing.

Education

George Cruikshank's education was otherwise erratic. He attended classes at an academy in Edgware, but probably not for long. Like many of his generation, his ‘life school was in the street’ (P. Cruikshank, 53) and watching by his father's side. For the religious services which his devout mother insisted he attend at the Scotch church in Drury Lane, George had scant sympathy. But he was an ardent disciple of the theatre, whether play-acting with his boyhood chum Edmund Kean or attending plays on every kind of stage, from patent theatres to rowdy music–halls. Another childhood friend, Thomas Joseph Pettigrew, became a distinguished physician and antiquarian who helped both George and Robert Cruikshank to various artistic commissions in later years.

When, on 1 February 1803, Napoleon declared war on Britain, all the Cruikshank males caught ‘scarlet fever’. Their father, Isaac, joined a Bloomsbury volunteer troupe while Robert and George drilled alongside with blackened mop handles and toy drums. Shortly thereafter Robert went to sea as a midshipman in the East India service; marooned on St Helena, he was given up for dead by his family until he returned, alive, in January 1806, having heard the fateful news of Trafalgar while on his way home. During Robert's absence, George aspired to replace him as a seaman. But Isaac's health was deteriorating, and he needed his son's assistance. Reluctantly, George agreed to remain in the studio, even hiding out on occasion from press-gangs. He tried, briefly, to study at the Royal Academy; the keeper and professor of painting, Henry Fuseli, told him he might go in, but ‘must fight for a seat’ (Jerrold, 1.72–3). He may have attended one course of lectures, but, as he confided in old age, the press of work ‘was so great that he had no leisure for the lectures or work of an art student’ (ibid.).

George Cruikshank was sketching competently as early as 1799; by 1803 he was supplying simple designs to wood-engravers for children's games and books. His father taught him the rudiments of etching into copperplates; at the age of thirteen he was executing the titles of his father's caricatures, and also putting in backgrounds, furnishings, and dialogue. When Robert returned home in the winter of 1806, George had surpassed him in skill; though the brothers worked side by side, and with their father, the youngest of the trio by virtue of his talent and vigour surpassed his elders. Younger siblings, Margaret Eliza and a boy who died, aged four, in 1810, added to the family's financial strains, so George's and Robert's independently earned income was crucial. Commissions multiplied. Many prints were collaborative efforts; Robert also painted miniature portraits and George produced hundreds of designs for advertisements, twelfth-night characters, drolls, songheads, and frontispieces. Principal patrons were the dealers Robert Laurie and Jemmy Whittle (old friends of Isaac Cruikshank's) and Johnny Fairburn, an easy-going, genial printseller in the City of London. By 1808 George was no longer marking his work with initials; he signed broadside prints with his full patronym: ‘G. Cruikshank’.

Early caricatures

The images Cruikshank inscribed derived not only from London street culture but also from the vivid pictorialism of the Bible, Aesop's Fables, Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, and Swift's Gulliver's Travels, and from the design vocabulary of visual satire sharpened and elaborated by such past masters as William Hogarth and contemporaries such as Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray. This vocabulary ranged from mimetic images through degrees of distortion to symbolic forms and beyond to rebuses, mock coats of arms, and pictorial puzzles. Napoleon, for instance, might be represented realistically in a portrait bust, or as Gulliver appeared to the king of Brobdingnag, or as ‘little Boney’, or as a cloven-hoofed devil, or concealed among violets. Caricaturists, competing daily for the public's coppers, had to be inventors and plagiarists, taking popular forms and changing them to hit the new day's fancy. George Cruikshank was the most fecund, original, and deft graphic satirist after Gillray. Between 1808 and 1811, as he lampooned such public events as the Peninsular War and private scandals around the court and Covent Garden, Cruikshank perfected a repertoire of types, lines, symbolic figures such as the quintessential Englishman John Bull, and ways of telling a story that catapulted him into the front ranks. By the age of twenty he was celebrated.

In April 1811 Isaac Cruikshank won a drinking match and collapsed comatose. He never recovered. Robert and George had to maintain their family; Robert, hoping to become a well-paid portraitist, eventually went off on his own, leaving George as the principal breadwinner. So far as we know, he housed his sister until her death in August 1825 and his mother until her death on 10 August 1853. All their support came from his drawings and etchings.

Major caricatures

From 1811 Cruikshank's inventiveness and superior artistry rapidly propelled him to primus inter pares. A caricature of state miners (January 1811), executed for a radical printseller, may be his first extensive political design completed without his father's help. Thereafter Cruikshank produced hundreds of prints, for conservative dealers such as Hannah Humphrey (who commissioned him to complete a few of Gillray's designs) and her nephew George Humphrey to radical publishers and, on occasion, to printsellers such as J. J. Stockdale who distributed pornography. Napoleon was a principal target. Cruikshank parodied his dispatches during the Russian campaign of 1812–13 (Boney Hatching a Bulletin or Snug Winter Quarters!!!, December 1812), and adapted themes and images from imported Russian caricatures to depict a heroic Cossack extinguishing a Napoleonic flat candle (Snuffing out Boney!, May 1814). Cruikshank never tired of inventing new ways to belittle the emperor and render him ridiculous: calling on familiar British folklore, he turned Napoleon into a Corsican toad in the hole, a Tiddy Doll on Elba hawking broken gingerbread kings, and a noble whose coat of arms, supported by devils, commemorates Bonaparte's crimes. When the decimated French army recruited 300,000 new troops to replace the hundreds of thousands lost during the Russian campaign, Cruikshank imagined French Conscripts for the Years 1820, 21, 22, 23, 24 & 25: a mutilated veteran musters infants who would rather play at ‘Peep bo’ or go ‘home to my Mamme’ (18 March 1813). In such ways Cruikshank, his brother, and the other pictorial satirists of the period kept up the home spirits and bolstered the resolve of foreign allies.

At the same time, many of Cruikshank's caricatures lampooned venal office-holders in Britain and the licentious, corrupt court of the prince regent, memorialized in one image as a huge whale spouting the ‘Dew of Favor’ onto his favourite ministers (The Prince of Whales, May 1812). In another image, Cruikshank castigates the regent's proclivity to fall in love with bosomy wives whose cuckolded husbands were bought off with court sinecures (An Excursion to R[agley] Hall, October 1812). He designed forty-one folding plates on marital and martial subjects for the radical publication The Scourge (1811–16), thirty-two plates for a rival, The Meteor (1813–14), eight for The Satirist (1813–14), and numerous individual plates for Samuel Fores, William Tegg, S. Knight, Fairburn, and other printsellers. He depicted boxing matches, disorderly tavern scenes, Cockneys, the great clown Joey Grimaldi, religious zealots, sporting crazes (Lady Hertford rides the regent splayed on a velocipede or ‘hobby’; Royal Hobby's, 20 April 1819), and excesses of fashion, like dandies in cinching corsets from a series of plates called Monstrosities burlesquing fashion, which appeared annually from 1816 to 1825.

Cruikshank often worked from suggestions by amateurs. George Humphrey, Frederick Marryat the novelist, ‘Alfred Crowquill’, and William Henry Merle provided ideas for many images. From 1815 Cruikshank's principal collaborator was the antiquarian book dealer and radical publisher William Hone. After the government failed to convict Hone of blasphemous libel in three trials during December 1817, publisher and artist collaborated on sixteen parodic pamphlets which Cruikshank illuminated with witty, allusive wood-engravings—‘Gunpowder in boxwood’, his brother called them (I. R. Cruikshank, The Revolutionary Association [print], 1821). As trade slumped and discontented labourers agitated for political and economic reforms, Hone and Cruikshank lampooned the government and attacked repressive laws. The Bank Restriction Note of January 1819, a mordant parody of an actual banknote which protests capital punishment for the passing of easily forged pound notes, was, Cruikshank later said, ‘the most important design and etching I ever made in my life’ (Jerrold, 1.93–4). Cruikshank and Hone continued in the vein of moderate radicalism, supporting freedom of the press but not universal suffrage, invoking Magna Carta, ancient liberties, and the constitution against governmental repression led by the home secretary Lord Sidmouth, and savaging republicanism, atheism, and the libertinism of the regent, the ‘Dandy of Sixty’. Among the most powerful of these propaganda pamphlets was The Political House that Jack Built, issued in December 1819 and inspiring conservative counterblasts such as The Real or Constitutional House that Jack Built.

When, at the death of George III on 29 January 1820, his eldest son became king and the long-estranged princess of Wales came back to England to claim her status as queen, Hone and Cruikshank took up Caroline's cause, along with City merchants, radical MPs, and William Cobbett. The pamphlets and toys Hone and Cruikshank invented, incorporating demotic imagery, children's verses, and radical propaganda, sold as many as 100,000 copies in a few days: The Queen's Matrimonial Ladder, an illustrated paperbound pamphlet incorporating ‘A National Toy’ in the form of a pasteboard ladder tracking the fourteen stages of the regent's ‘progress’ as persecutor of his wife, went through dozens of printings. The most powerful image, an adaptation of Gillray's Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion (1792), turns George IV into a gross, fuddled inebriate whose ‘Qualification’ (title of the plate) for matrimony (in 1795) had been that he was:

In love [with other women than his betrothed], and in drink, and o'ertoppled by debt;

With women, with wine, and with duns on the fret.

(W. Hone, [text of] The Queen's Matrimonial Ladder [pamphlet], 1820)

To spare himself from such devastating caricatures, in June 1820 the king directed that Cruikshank be paid £100 ‘not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation’, and in the following month both George and Robert Cruikshank had their round trips to the royal pavilion at Brighton paid in order to negotiate a further easing of their satiric representations (George, 10.xii). These royal tactics were unavailing. Graphic and verbal satirists continued to assault their king, and George IV did not help matters. His vanity, fear of mob ridicule, and venality made him and his brothers, in the words of the hard-pressed duke of Wellington a few years later, the ‘damn'dest millstone about the neck of any Government that can be imagined’ (A. Briggs, The Age of Improvement, 1783–1867, 1959, 186). (Impressions of all the prints referred to above are held in the British Museum.)

Book illustration

But the tempest over the mistreatment of Queen Caroline blew over quickly, leaving Hone and Cruikshank without cause or occupation. Hone withdrew into antiquarian research and Cruikshank commenced a second career, as book illustrator. His first significant venture, with his brother, Robert, and the writer Pierce Egan, was a rollicking account entitled Life in London (1820–21). Their knowledge was gained first-hand: Hone warned his friend Childs that unless he foreswore ‘late hours, blue ruin [gin], and dollies’ he would destroy himself (MS letter, Hone to Childs, 11 Jan 1821, Berg collection, New York Public Library). But George and his brother preferred the company of pugilists, journalists, jolly tars, gamblers, Grub Street hacks, Bacchanalians, and actors; often he would come home with the milk in the morning reeking of tobacco and beer and laugh while his sister-in-law scrubbed his face and his mother belaboured him with her fists.

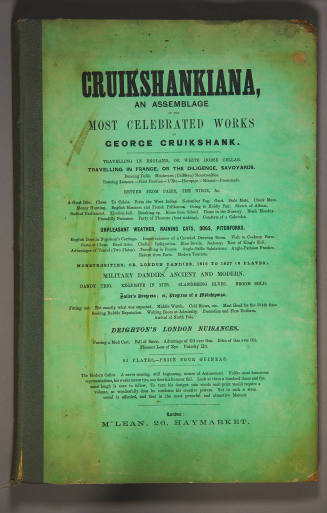

Other illustrations soon followed, chief among them being those for two volumes translating the brothers Grimm's fairy tales into English (German Popular Stories, 1823–6). These delicate copperplate vignettes, so different from the coarser political satires of the preceding decade, evoked a powerful response from John Ruskin, who, remembering them from his nursery days, called the etchings ‘the finest things, next to Rembrandt's, that, as far as I know, have been done since etching was invented’ (Ruskin, The Elements of Drawing, 1857, in Works, 15.222). Starting in 1826, Cruikshank issued his own albums, plates independent of letterpress which contained comic depictions of scenes, characters, and fads: Phrenological Illustrations (1826) was followed by Illustrations of Time (1827), four series of Scraps and Sketches (1828–32), and My Sketch Book, in nine parts from 1833 to 1836. In 1828 Cruikshank drew for Sebastian Prowett, a Pall Mall publisher with a considerable interest in the fine arts, images of an Italian puppeteer performing the conjugal endearments of one of England's most beloved couples, Punch and Judy. It was largely from looking at these comic vignettes and albums that Charles Baudelaire decided Cruikshank's ‘distinctive quality’ was ‘his inexhaustible abundance of grotesque invention’. Baudelaire acknowledged his other strengths, including ‘delicacy of expression’ and ‘understanding of the fantastic’, but felt that Cruikshank's characters were sometimes more vital than conscientiously drawn (C. Baudelaire, ‘Some foreign caricaturists’, in Selected Writings on Art and Literature, ed. and trans. P. E. Charvet, 1972, repr. 1992, 23–4). No doubt Baudelaire would have agreed with many other critics on the artist's inability to portray female beauty. Nevertheless, Cruikshank's sketches of street scenes influenced Henry Monnier's albums of the 1820s and 1830s; and in succeeding generations Paul Garvani, Gustave Doré, and the Goncourt brothers disseminated Cruikshankian subjects and designs to French audiences.

Cruikshank married Mary Ann Walker (b. c.1807) in her parish of Dunstable in Bedfordshire on 16 October 1827. The couple was childless, and until she died in 1849 Mary Ann suffered from ill health, possibly tuberculosis. Settled now into domesticity in a Pentonville terrace house, Cruikshank sought more steady income. One of his hopeful ventures was a comic almanac, issued annually, comprising jokes, poems, stories, lampoons, and full-page plates representing monthly events. These publications, like many other of his independent publications, were issued by Charles Tilt who, along with his successor, David Bogue, remained a principal publisher until the 1850s. The first few years of Cruikshank's Comic Almanack (1835–53) went well; William Makepeace Thackeray supplied stories in 1839 and 1840 and the pictures were capital. But it became difficult to sustain invention over the decades, and competition from Punch's Almanack (beginning December 1844), which many including Charles Dickens saw as an imitation of Cruikshank's, eventually doomed the artist's venture. Another project initiated in 1835 was to provide comic steel-engravings to Fisher & Son's Anglo-French edition of Sir Walter Scott's fiction, the capstone to five years during which George had produced illustrations of classic eighteenth-century novels for the publisher Roscoe's Novelists Library and developed what Frederick Antal called an ‘average-European’ style (Hogarth and his Place in European Art, 1962, 191).

Cruikshank met Charles Dickens through John Macrone, a young Manxman preparing a fourth edition of Harrison Ainsworth's novel Rookwood with illustrations by Cruikshank (1836). Macrone had proposed to Dickens that his ‘sketches’ of London life, then being printed in various periodicals, be collected in several volumes and reissued with illustrations by Cruikshank; Dickens agreed. On 17 November 1835 Dickens called on the artist at his home and studio in Amwell Street, Pentonville. As over the next year they worked together on two series of Sketches by Boz (first series, two vols., February 1836; second series, one vol., December 1836), the relationship warmed from wary professionalism to bibulous bonhomie, interrupted by an occasional outburst of temper, of which each collaborator had his share. These volumes were a great success, both on account of Dickens's rising popularity and because Cruikshank's plates introduced deft and spirited graphic commentaries on the text and the town. In December 1836 the publisher Richard Bentley, seizing an opportunity to sign up the most popular urban artists of the day, hired Dickens to edit, and Cruikshank to illustrate, his new magazine, Bentley's Miscellany. Into that journal, from January 1837 to November 1843, Cruikshank poured some of his best work, especially in illustrating Oliver Twist and Ainsworth's follow-on, Jack Sheppard. Both texts were significantly enhanced by the plates, which often served as the armatures upon which the many dramatic renditions of the novels were staged.

Although Dickens's literary adviser, John Forster, objected to the designs for the illustrations to the last instalments of Oliver Twist, and Dickens too asked for one of the plates to be redrawn, other contemporaries thought these the summit of the artist's achievement. Richard Ford, writing in the Quarterly Review, asked why Royal Academicians ‘have not ere now insisted on breaking through all puny laws’ and voted ‘this man of undoubted genius his diploma’ (64, June 1839, 102). Fagin in the Condemned Cell was roundly praised at the time of its publication; Cruikshank often afterwards enacted stories about its creation; and even Dickens used it as a point of reference, telling his last illustrator, Luke Fildes, that the picture of the Rochester cell in which John Jasper would be incarcerated in Edwin Drood should be ‘as good a drawing’ as Cruikshank's (F. G. Kitton, Dickens and his Illustrators, 1899, 214).

The decade between 1835 and 1845 was, for many commentators, the high water mark of Cruikshank's artistic life. The intense focus on his few projects with Dickens, and the rancorous disputes that broke out in later decades, have led biographers to imagine that Oliver Twist was the climax of the artist's achievement and that his inability to satisfy Dickens commenced his long falling-off. In fact Cruikshank had decades of acclaim behind him, for a variety of images and social campaigns, before he met Dickens, who was dubbed ‘the CRUIKSHANK of writers’ by the Spectator (26 Dec 1836, 1234). And the very fame that book illustration brought to the middle-aged draughtsman had its downside: if his plates were attached to books (and copyrighted in the name of the publisher who issued those books), then when the titles went out of print so too did the illustrations, an arrangement over which the artist had no control. While Cruikshank's extraordinary assemblage of wood-engravings and steel etchings for Ainsworth's historical novels such as The Tower of London (1840) and Windsor Castle (1842–3, wood-engravings by W. Alfred Delamotte) deserves to rank among his most sustained, original, and brilliantly executed productions, the texts to which they were attached have so fallen from sight that the plates can hardly be found.

It is also the case that in the 1840s Cruikshank's work begins to bifurcate. He continues to etch many light-hearted or melodramatic scenes, but he also begins to insert a more rigorous, less ‘devil may care’ morality into some of his work. Domestic idyll is threatened not only by scary railroad monsters smashing into the kitchen—a representation of the railway mania that zigzagged the stock exchange in the 1840s—but also by satanic forces unleashed by individuals unable to control their passions. His etchings for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 (1845) ‘strike savagely off the page’, as the novelist John Fowles has observed (Fowles, xxvii). Whereas Maxwell tried to maintain impartiality in his narrative, Cruikshank indicts both sides through portrayals that have often been compared to Goya's Disasters of War.

The Bottle

Two years later this strain of excoriating remonstrance issued forth in the first of Cruikshank's many mid-century diatribes against personal indulgence: The Bottle (1847). ‘The Follies of youth’, he noted in his diary on 27 September 1846, ‘punish us in our old age’ (Patten, 2.234).

Prompted by a Manchester reformer, Joseph Adshead, Cruikshank arranged to produce a set of complex narrative plates, similar to those Hogarth had issued a century earlier, promoting temperance. The artist chose an experimental medium, glyphography, which reduced the costs of the prints and thus might make them widely available to the working classes. It was, however, a rather crude process, so Cruikshank had to invent designs that did not depend on delicate lines or multiple gradients of black. The decline and fall of a respectable labourer and his family, tracked in eight plates which were issued on various qualities of paper and later in reduced size sometimes accompanied by verses supplied by Charles Mackay, struck many as extraordinarily effective. Matthew Arnold composed a sonnet in tribute and Dickens urged Forster to a complimentary notice. But Dickens, in a disagreement that was eventually to split the former collaborators asunder forever, cautioned that the consumption of beer, wine, and spirits should be understood as originating ‘in sorrow, or poverty, or ignorance’, not simply in a thoughtless tipple to celebrate the day (Charles Dickens to John Forster, 2 Sept 1847, in The Letters of Charles Dickens, ed. M. House and others, 1965–, 5.156–7). For Dickens, a moderationist, social remedies, especially education and a living wage, would eliminate excess drinking; for Cruikshank, who knew from his own family the ravages of alcoholism, drinking was a destructive habit that could only be stopped by will-power. Indeed, once he had completed his graphic series, Cruikshank realized he ought to heed his own lesson and turn teetotal himself. He did, and until his death he lectured, often somewhat intemperately but usually to appreciative audiences throughout the British Isles, on the evil effects of drink and the beneficial results of sobriety. He refused, however, to sign the pledge because ‘pledged to the Almighty on the faith and honour of a gentleman’ (Whittaker, 233).

The Bottle garnered much acclaim; it became a standard decoration in temperance rooms and a customary prize at teetotal gatherings. But neither it nor its equally potent successor, The Drunkard's Children (1848), made money. Cruikshank's supporters could not understand why the artist was poor, after more than a quarter century when his name had been a byword for prodigious invention, humour, and social commentary. Unknown even to some of his closest friends, however, commissions for illustrations came less frequently with each passing year, neither the Comic Almanack nor any of the periodicals he initiated in the 1840s including Omnibus (1841–2) and Table Book (1845) yielded substantial sums, and Mary Ann was dying. While playing in Dickens's amateur theatrical company during the mid-1840s reunited Cruikshank with cronies of earlier days and with the principals of Punch, for which he refused to work, he was not really a member of the inner circle. Tolerated more as an eccentric, sometimes unmannerly, Cruikshank was increasingly isolated from the most popular humorists of the day and relegated to second-rate commissions for third-rate projects.

Domestic concerns

After Mary Ann's death on 28 May 1849, Cruikshank collapsed. As he explained to his oldest friend, William Henry Merle:

The many years of anxiety, & the desperate struggle that I have had to keep up my position—as a poor Gentleman—the long—years long, illness of my poor wife—and then the crushing blow of her death! was altogether too much for my strength to bear ... for the first time in my life—[I] could not work!! (to Merle, 6 Nov 1849, in Patten, 2.277)

It was not just the loss of his wife that had overwhelmed him. Many of his old collaborators—authors and publishers—were dead; one of the last, Frederick Marryat, had succumbed in August 1848 after learning of the death of his beloved son at sea. The temperance plates yielded scant revenue, and the hoped-for American sales did not materialize. Chartism and the revolutions of 1848 further dampened interest in Cruikshank's art. And he continued the generosity of his youth, lending money whenever he had an extra sovereign and then growing surprised and eventually disappointed when the loans were not returned. Himself often in debt, especially to Merle, Cruikshank had managed his slender resources so thriftlessly that unless he could sell new work—he owned very little of his previous production—he could not eat. He was, to his surprise, bankrupt; alluding to the California gold rush, he commented to Bogue ruefully: ‘I [am] ... more convinced than ever, that England is not California’ (3 Feb 1849, in Patten, 2.269).

Slowly Cruikshank returned to art, this time essaying oil painting, which he had attempted decades earlier. The results were, on the whole, unsatisfactory. His lifetime practice of working on a small scale with delicate instruments was quite wrong for the bolder gestures required by large canvases; ‘the etching point feeling was always in his fingers’, he conceded, when a ‘painter should paint from his shoulder’ (Jerrold, 2.146, 139). He sold a few pictures, usually of literary or humorous subjects. An early effort, The Disturbed Congregation (oil on panel, 1849; Royal Collection), depicts an outraged beadle (modelled by his nephew Percy Cruikshank) giving a potent look of reprimand to a guilty young lad (Percy's boy, George) who has dropped his peg top in church. The prince consort purchased it for 30 guineas, but royal patronage dried up thereafter. In the 1860s Cruikshank expended years of labour on a gigantic canvas warning against the evils of drink, The Worship of Bacchus (1862; Tate Collection), and on the engraving from it that he published along with an explanation of the hundreds of incidents displayed in his ‘diagram of drunkenness’. But this project, like almost all the others Cruikshank tried in the last thirty years of his life, failed. The time and effort he expended on graphic temperance sermons exceeded what any of his conservative, middle-class, and working-class teetotal admirers were willing to pay for, either in an outright contribution or to purchase a plate.

Both professional and domestic prospects seemed to brighten around the time of the Great Exhibition. Cruikshank teamed up with Henry Mayhew, as he had for a couple of comic narratives in the late 1840s, to produce an illustrated serial, to be issued monthly during the exhibition, about the misadventures of a Cumberland family who travel down to London on the spur of the moment. 1851, or, The Adventures of Mr. and Mrs. Sandboys, began bravely enough with a bravura frontispiece showing the whole world going to the exhibition. Unfortunately, neither author nor artist could sustain the story. In the end Mayhew barely cobbled together enough text to fill his pages, and Cruikshank drew plates that sometimes bore no relation to the letterpress. The serial didn't sell, and neither did Cruikshank's plain or coloured etching of the opening of the exhibition, which had to compete with many other single plates and a huge wood-engraving in the Illustrated London News. Prince Albert received a copy early in July.

In the preceding year, on 7 March 1850, Cruikshank had remarried. Eliza Widdison (1807–1890), niece of the publisher Charles Baldwyn who had commissioned the first volume of German Popular Stories back in the 1820s, was the same age as Mary Ann; she had received a little education and survived on the small annuities paid to her widowed mother and aunt with whom she lived. Although her resources were meagre, she clung to her status as the daughter of a gentleman. The wedding, by licence, took place at Holy Trinity Church, Islington. Cruikshank, Eliza, his mother, her mother and aunt, a married cook, and a maid of all work moved to 48 Mornington Place, renamed 263 Hampstead Road in 1864. The transformation of the hot-headed bohemian of the regency era into a sober householder who even renounced tobacco seemed complete.

But it was not. Eliza was a reliable, kindly woman who adored her husband and believed him to be the champion of the age. She and the ageing relatives, who all died between 1851 and 1853, looked after his every want. But something prompted Cruikshank to stray. Shortly after his mother's death the housemaid, Adelaide Attree (bap. 1831, d. 1914), confessed that she was pregnant. Eliza was sympathetic but had to let her go. Eliza did not know that her husband was the father, and that he set up Adelaide in a flat nearby that doubled as a studio. And as a nursery. Adelaide gave birth to eleven children, ten surviving infancy: George Robert (b. 20 Nov 1854), Annie Adelaide (b. 1858), William Henry (b. 12 Jan 1860), Albert Edward (b. 10 Jan 1863), Alfred Mills (b. 1 March 1865), Eliza Jane (b. 16 March 1867), Ada Rose (b. 22 Sept 1868), Emma Caroline (b. 15 Nov 1869), Ellen Maude (b. 9 March 1873), and Arthur Attree (b. 17 March 1875). The presumption remains that these were all Cruikshank's children. He did what he could to provide for them, sending money surreptitiously through confidential servants or friends. There is evidence that Eliza knew something about the other family, but not perhaps its extent or her husband's full involvement. Sustaining two separate households on slender means, presenting himself to his loving wife as an upright, honest, and thoroughly principled artist, and keeping the second family a secret forced Cruikshank into financial expedients and concealments that often shortened his temper. These strains also impelled him to look for work in any place where it could be found.

Temperance

One activity that consumed huge amounts of time from 1847 to the end of Cruikshank's life was attendance at temperance meetings. He became an eccentric and beloved figure, his own self-caricature, the St George of water drinkers. Dora Montefiore was fascinated by him when as a child she saw him in the 1860s: ‘he had a long mesh of iron grey hair which he trained across the top of his head and kept in its plac