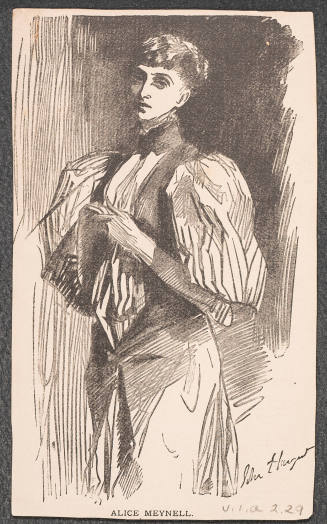

Alice Meynell

LC Name authority rec. n50036625

LC Heading: Meynell, Alice, 1847-1922

Biography:

Meynell [née Thompson], Alice Christiana Gertrude (1847–1922), poet and journalist, was born at Barnes, Surrey [Barnes is actually a district in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/tgn/1004045], on 11 October 1847, the younger daughter of Thomas James Thompson (1809?11–1881) and his wife, Christiana Jane Weller (1825–1910), daughter of Thomas Edmund Weller (1799–1884) and his wife, Elizabeth Dixon Southerden.

Thomas James Thompson was born in Jamaica, the son of an Englishman, James Thompson, and his Creole mistress. His grandfather Dr Thomas Pepper Thompson had emigrated from Liverpool and had grown rich on the ownership of sugar plantations, and when his son James predeceased him Dr Thompson brought his grandson to England. At his death he left him a substantial legacy. After leaving Cambridge without taking a degree, Thomas James dabbled in politics and the arts. He was a widower in his mid-thirties when he married Christiana Weller at Barnes parish church on 21 October 1845. Their two daughters, Alice, and the elder Elizabeth (1846–1933) [see Butler, Elizabeth Southerden, Lady Butler], were educated entirely by himself; his teaching was to be a great influence on them.

Christiana Weller, to whom Thompson was introduced by his friend Charles Dickens, was a concert pianist and an amateur painter. It was perhaps from her that Elizabeth inherited a talent which was to make her famous as a painter of battle scenes under her married name, Lady Butler.

Thompson's prosperity did not last, and it was partly for reasons of economy that he and his family travelled constantly, living in rented houses which were sometimes in England but more often in Italy. From 1851, when Alice was four, they seldom stayed long in the same place, but it was the Ligurian coast of Italy that they chiefly frequented—Albaro, Nervi, Sori, Portofino (then a fishing village)—and the two young girls learned to speak Italian fluently, but with a Genoese accent. Alice's legacy from these years was a lifelong love of Italy.

In 1868 the Thompsons stayed for a time at Malvern, Worcestershire, and it was there that Alice took instruction and was received into the Roman Catholic church, on 20 July at St George's, Worcester. As an Anglican she had been religious from childhood. Her mother had joined the Catholic church some time before without telling her family. It seems that there was no later discussion on the matter between her and Alice, as the parents apparently were unaware of their daughter's intention. Thomas James was to convert to Catholicism shortly before his death in 1881. Alice's faith became the most important thing in her life. ‘I saw when I was very young’, she wrote many years later, ‘that a guide in morals was even more necessary than a guide in faith. It was for this that I joined the Church. Other Christian societies may legislate, but the Church administers legislation’ (A. Meynell to her daughter Olivia, n.d., Meynell MSS). And, again in later years, she said that the antithesis of slavery was not so much liberty as voluntary obedience which gives the truest freedom (Meynell MSS).

In the course of Alice's instruction at Worcester by Father Dignam, a young Jesuit priest, the two became friends, but this later developed into a hopeless love. Dignam asked to be sent abroad and communication between them ceased. Alice had been writing poetry for the two or three years prior to her conversion, and now her deep sorrow, though unnamed, was the subject of several fine poems which would later become well known, among them ‘Renouncement’, a piece often found in anthologies. Her first published poems appeared as Preludes in 1875 and met with praise from Tennyson, Coventry Patmore, Aubrey de Vere, and John Ruskin. Wilfrid John Meynell (1852–1948), a young Roman Catholic journalist in London, read a review of her work in the Pall Mall Gazette, and his admiration for the poems led to a meeting. The couple fell in love and, after overcoming parental opposition over Meynell's lack of money, they were married in London at the church of the Servite Fathers on 16 April 1877.

The Meynells settled in Kensington, at 47 Palace Court, and worked hard at journalism, which was their only income. Their first child—a son—was born in 1878, and thereafter they had seven more children, of whom one died in infancy, but Alice Meynell managed to be a very loving mother while continuing the essential journalistic work. Wilfrid Meynell, with Alice's help, edited the Weekly Register (known to the family as The Reggie) for seventeen years, and both made considerable contributions to it. During one of Wilfrid's rare absences, Alice edited it by herself and wrote to him: ‘My own Love ... Never again shall I fear taking The Reggie for you; I am going in at a canter with both hands down’ (A. Meynell to W. Meynell, 1893, Meynell MSS).

From 1883 to 1895 the Meynells also edited Merry England, a monthly. On a fairly regular basis Alice contributed articles, mainly of literary criticism, to The Spectator, The Tablet, the Saturday Review, The World, and the Scots Observer. Her first volume of essays, The Rhythm of Life, published in 1893, consisted mainly of work reprinted from periodicals. Of the essay that gave the book its title, W. E. Henley, editor of the Scots Observer, wrote that it was ‘one of the best things it has so far been my privilege to print’ (W. E. Henley to A. Meynell, 1889, Meynell MSS). In 1893 Alice Meynell began to write a weekly column in the Pall Mall Gazette which was widely read and much admired, and she became sought after by lionizing hostesses.

In this busy household the children, as they grew older, sat under the dining-room table editing their own ‘magazine’, while their parents used the table-top as their working area. Two of the children, Viola Mary Gertrude Meynell (1885–1956) and Francis Meredith Wilfrid Meynell (1891–1975), both became well-known writers, Viola publishing a memoir of her mother in 1929 and one of her father in 1952.

Alice Meynell became acquainted with Coventry Patmore through her review of his poems, and an increasingly close friendship developed between them. For her it was an amitié amoureuse but Patmore (widowed twice and married to his third wife) fell in love with her. She felt that their relationship was a threat to her happy marriage, and thus severed all communication with him.

Francis Thompson (not a relative) had become a part of the Meynells' lives through their editorship of Merry England, and from then until his death in 1907 they cared for this brilliant but most impractical poet as if he were one of their own children. He loved Alice Meynell with hopeless adoration, and George Meredith, too, had fallen in love with her. She had an intense admiration for the poetry of Patmore, Thompson, and Meredith and was very proud of their public acclaim of her own work, but their love for her was not always easy to deal with, and it created jealousy among them. Her capacity to inspire deep affection in people of all ages was intensely strong throughout her life.

Five more volumes of Alice Meynell's essays appeared, as well as a book on Ruskin, and an anthology of Patmore's poetry and one of English lyric poetry. During a period of almost twenty years, when motherhood and journalism claimed her time, she wrote no poetry, but after 1895 (the year in which she was mentioned as a possible Poet Laureate) she returned to poetry, and this second part of her literary life produced some of her finest work, including some poems on the First World War. She had always been a staunch supporter of women's suffrage and more general principles of women's rights—at the age of eighteen she had written in her diary: ‘Of all the crying evils in the depraved earth ... the greatest, judged by all the laws of God and humanity, is the miserable selfishness of men that keeps women from work’ (Schlueter and Schlueter, 323). This questioning of women's social status is seen in her later work, especially in the meditative Mary, the Mother of Jesus (1912; new edn 1923).

In the year before she died Alice Meynell experienced a final creative period of productivity, her outburst of song, like the swan's, preceding her silence. In her poems written then, as in her prose, there is tightly packed thought, with every line and paragraph having been subjected to a stern discipline. The rules of her art echoed those of her life. She died at her London home, 2A Granville Place, on 27 November 1922 and was buried in Kensal Green cemetery. Her husband survived her.

June Badeni

Sources V. Meynell, Alice Meynell: a memoir (1929) · J. Badeni, The slender tree: a life of Alice Meynell (1981) · P. Schlueter and J. Schlueter, eds., An encyclopedia of British women writers (1988) · Meynell MSS, Greatham, near Pulborough, Sussex · private information (2004) · DNB · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1923) · m. cert. [Thomas James Thompson and Christiana Jane Weller] · d. cert. [Thomas James Thompson] · d. cert. [Christiana Jane Thompson]

Archives Boston College, literary papers · CUL · Hunt. L., letters · L. Cong. · NRA, corresp. and literary papers · priv. coll. :: Bodl. Oxf., letters to Elizabeth, Lady Lewis · Ransom HRC, corresp. with John Lane · Somerville College, Oxford, letters with poems to Percy Withers · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Edmund Gosse · U. Nott. L., letters to Fred Page · UCL, letters to Arnold Bennett

Likenesses A. Stokes, watercolour sketch, 1877, priv. coll. · J. S. Sargent, pencil drawing, 1895, NPG · W. Rothenstein, lithograph, 1897, NPG · W. Rothenstein, two lithographs, 1897, BM, NPG · S. Schell, platinum print photograph, 1913, NPG [see illus.] · O. Sowerby, drawing, 1921, priv. coll. · J. Russell & Sons, photograph, NPG · photograph, NPG

Wealth at death £538 17s. 10d.: administration, 18 Oct 1923, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

June Badeni, ‘Meynell , Alice Christiana Gertrude (1847–1922)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2010 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/35008, accessed 30 Sept 2015]