Image Not Available

for George Wyndham

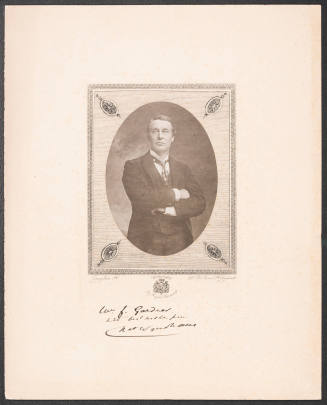

George Wyndham

London, 1863 - 1913, Paris

LC heading: Wyndham, George, 1863-1913

found: Who's who 2010 & who was who WWW site, 1 Sep., 2010: (Wyndham, Rt Hon. George; b. London, 19 Aug., 1863; d. 8 June, 1913)

Biography:

Wyndham, George (1863–1913), politician and author, was born in London on 29 August 1863, the eldest son in the family of two sons and three daughters of Percy Scawen Wyndham (1835–1911), politician and country gentleman, and his wife, Madeline Caroline Frances Eden (d. 1920), the daughter of Sir Guy Campbell, first baronet. He was educated at Eton College, and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, from where he was commissioned into his father's regiment, the Coldstream Guards. He served in Egypt during the Suakin campaign of 1885: he later played a prominent role as an officer of the Cheshire yeomanry. On 7 February 1887 he married Sibell Mary, Countess Grosvenor (1855–1929), daughter of Richard George Lumley, ninth earl of Scarbrough, and widow of Victor Alexander Grosvenor, Earl Grosvenor. They had one child, Percy Lyulph, born in December 1887, who followed his father into the Coldstream Guards, and who was killed in action in September 1914. Wyndham's stepson was Hugh Richard Arthur, second duke of Westminster (1879–1953).

Military and parliamentary service were engrained in the traditions of the Wyndham family, as in other tory county dynasties. Wyndham followed his father into both the army and the House of Commons, and served as MP for Dover from 1889 until his death in 1913. Ireland was also important to the family: Wyndham had connections with the Irish landed gentry (his uncle the second Lord Leconfield owned 44,000 acres in counties Clare and Limerick, while the seventh earl of Mayo, proprietor of 7500 acres in Kildare and co. Meath, was his cousin). He had a rather more distant, if much better advertised, connection with Irish insurgency (his maternal great-grandfather was Lord Edward FitzGerald, the rebel leader of 1798). Wyndham's first political employment came in 1887, as private secretary to Arthur Balfour (chief secretary for Ireland, 1887–91): later, when returned as MP for Dover, he served as Balfour's parliamentary private secretary. Wyndham was associated with the successes of Balfour's administration: he received a training in Balfourian strategy, and made personal connections that would serve him later in his ministerial career.

The Souls and literature

But Wyndham possessed other social and political networks, most notably in the Souls, the aristocratic clique formed in 1887 in reaction to the philistinism and heartiness of the prince of Wales's Marlborough House set. Wyndham was central to the Souls, partly because of his family connections, and partly because of his association with Balfour, who was the guru of the group. The Souls were a carry-over from the Crabbet Club, which revolved around Wyndham's cousin Wilfrid Scawen Blunt: but Wyndham—and also his sisters Pamela and Mary [see Charteris, Mary Constance]—were much more central to the life of the new connection than of the old. The Souls valued intellectual dexterity, physical beauty, and (though this was less explicit) high-born connections; and Wyndham satisfied each of these requirements in full. His brightness was never much in doubt, although the diffuseness of his thought and his tireless loquacity wearied his friends. His good looks caught the notice of fellow Souls and other admiring contemporaries: Margot Asquith thought Wyndham and Lord Pembroke ‘the handsomest of the Souls’ (Asquith, Autobiography, 185). However, this handsomeness was complemented by a rather dandified and jumpy manner, which irritated even his social peers, and certainly alarmed back-bench tories: Arthur Lee observed that

the rank and file [of the party] had never cottoned to his dandified and over-polished parliamentary manners, which led one old Tory member to mutter in my hearing after one of Wyndham's Burke-conscious perorations, ‘damn that fellow, he pirouettes like a dancing master’. (Good Innings, 128–9)

Wyndham once claimed, amid the disappointments of his later career, that he was ‘an artist who has allowed himself to drift into politics’ (Mackail and Wyndham, 2.656). His literary and artistic ambitions have indeed sometimes been seen as an alternative to, or diversion from, his political life. This is probably a misperception. Wyndham's literary efflorescence certainly came when the tories were out of office (1892–5) and when he had been apparently passed over for ministerial preferment (1895–8). He was an admirer of W. E. Henley, and wrote extensively for Henley's newspapers, including the imperialist weekly the National Observer. Wyndham also contributed to Henley's series of Tudor Translations, for which he edited North's Plutarch (1895). Wyndham shared some of Henley's broader artistic vision, including a passion for the work of Auguste Rodin (he commissioned a portrait bust from the sculptor). His other literary or literary–historical endeavours included an edition of The Poems of Shakespeare (1898), Ronsard and La Pléiade (1906), and an address, given as lord rector of the University of Edinburgh, The Springs of Romance in the Literature of Europe (1910). His Essays in Romantic Literature were published posthumously, in 1919.

Much of this work expressed an artistic vision which was well integrated within Wyndham's political philosophy. He was a tory romantic, who unblushingly believed that the sum of human happiness was as great in the feudal era as in his own day. He identified the governing idea of his own age as ‘cosmopolitan individualism’: this had suffocated the last vestiges of romance and the feudal ideal at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Cosmopolitan individualism was associated with a surfeit of democracy and with the vagaries of international finance: Wyndham was suspicious of both, and saw democracy as a precursor to ‘Caesarism’ and capitalism as antagonistic to his vision of Englishness. His anger at ‘cosmopolitan finance’ came, especially in later life, to be expressed in directly antisemitic terms. After Henley's death (in 1903) he found a receptive and stimulating audience for such speculations with Hilaire Belloc and (to a lesser extent) G. K. Chesterton.

Chief secretary for Ireland

Imperialism, for Wyndham, was the only serious alternative to the rising menace of socialism. When (in 1898) he was appointed as under-secretary at the War Office, he had the opportunity to meld this imperialist vision with his extensive knowledge of the army. He had, in addition, two clear political opportunities: first, his superior, the secretary of state, was the marquess of Lansdowne, and thus in the House of Lords; and second, the outbreak of the South African War (in October 1899) gave his own relatively junior office an enhanced significance. The scale of the conflict, and the reverses experienced by the British in the early months of the war, made Wyndham's position at first both administratively arduous and politically vulnerable. But he defended British policy with some skill, and one speech in particular—delivered in the Commons on 1 February 1900—commanded widespread admiration.

This enhanced parliamentary standing, combined with mounting British military successes on the front, meant that Wyndham was assured of ministerial promotion. In October 1900 he was appointed chief secretary for Ireland. He was still outside the cabinet (the lord lieutenant for Ireland, Earl Cadogan, held onto this palm); but his new office was widely recognized as one of the most difficult in British politics. And his appointment—at the age of thirty-seven—identified him as one of the high-fliers among a remarkably talented younger generation of Conservative politicians.

In Ireland Wyndham followed, broadly, the strategies laid down by Balfour. Some attention was paid to the social and economic welfare of the Irish people, and determined efforts were made to advance land purchase, a central feature of Balfour's administrative programme in the late 1880s. Wyndham's tenure of the Irish Office coincided with a period of centrist political speculation, both in Britain and in Ireland: a land conference, held in 1902 and uniting landlord and tenant representatives, together with the Irish Reform Association were perhaps the most tangible expressions of this—short-lived—consensual impulse in Irish politics. The report of the land conference, which advocated an ambitious extension of the land purchase programme, formed the basis for the Land Act of 1903, known as the Wyndham Act: the measure has been seen as Wyndham's main achievement in Ireland, and it therefore marked the summit of his political career. He believed that the Land Act represented the first of a series of legislative coups by which he and his supporters would resolve many of the central dilemmas of Irish political life. The confidence was characteristic, but misplaced. Efforts to establish a Catholic university foundered in 1904. In the summer of 1904 the Irish Reform Association produced a proposal outlining a limited form of administrative devolution for Ireland. This was soon disowned by Dublin Castle. But Wyndham's senior civil servant, Sir Antony MacDonnell, had been involved in the discussions that had preceded the publication of these documents; and it came to be believed that the chief secretary himself lay behind the initiative. Denounced by Irish Unionists (who saw a betrayal of principle) and by many Irish nationalists (who feared that a relatively consensual British administration might demoralize the national cause), Wyndham resigned office in March 1905. The devolution affair hung like a pall over the remaining years of his political career.

Wyndham's fall raises wider issues concerning his administration of the Irish Office. He once declared, playfully, that Ireland ‘can be governed only by conversation and arbitrary decisions’ (Letters, 2.6). It seems clear that he could be an incurably verbal and sometimes cussed minister. The editor of his letters, J. W. Mackail, remarked that Wyndham was a good talker but a bad listener; Margot Asquith complained perceptively that Wyndham was

never in proportion, because he cannot take in a [third] of what he gives out—and when he allows you to state your point of view you find yourself modifying your difference so as not to come out too crudely against his many long, keen, almost perorated convictions. (Margot Asquith's diary, 28 March 1896)

Wyndham was passionate about ideas in politics and literature. He was a man with a very keen sense of honour; but this was also compatible with a sometimes cavilling or excessively legalistic approach to the truth: Margot Asquith, again, thought him ‘not only nerveless but not rigidly straight’ (ibid., 28 Oct 1905). There seems little doubt in fact that Wyndham debated the idea of devolution with political friends in 1903–4, even if he finally (and belatedly) grasped the political impossibility of the venture.

Wyndham had also, as a tory romantic, some bonds of empathy with aspects of Irish nationalism: he was certainly fired by his reading of Irish history. He had a vaulting self-confidence: ‘I shall pass a Land Bill, reconstruct the Agriculture Department and Congested Districts Board, stimulate Fishing and Horse-breeding; and revolutionize Education’, he announced, without conscious irony, in January 1902 (Mackail and Wyndham, 2.436). In addition he had an almost Gladstonian sense of mission with regard to Ireland: the Irish, he declared in October 1903, ‘do still believe in me, and tremble towards a belief in the Empire because of their belief in me’ (Letters, 2.79). But for those Irish who already professed a belief in the empire, he and his administration had little time. Romantic Irish nationalism was closer to Wyndham's most fundamental convictions than the evangelical vulgarities, the urban grubbiness, and the commercial banalities of Ulster Unionism.

Wyndham's obsessive and passionate temperament, combined with the thinness of his political skin, meant that the last months of his time in Ireland were marred by a physical and mental breakdown: Arthur Balfour was ‘seriously alarmed’ by the belief that Wyndham's nerves had been ‘utterly ruined’, and that he was ‘really hardly sane’ (Balfour to Sibell Grosvenor, January 1905, Wyndham MSS). He had pursued his desperate crusade through an adrenalin-charged and oppressive routine of work: he had come to rely increasingly on drink. By the time of the devolution crisis, he had no resources upon which to draw. His racked health was the occasion, though not the reason, for his resignation from office. This very public collapse in health (regardless of the serious political questions involved) caused lasting damage to his credibility.

Disillusion and death

Wyndham survived the electoral decimation of the tories in December 1905, and was active in campaigning for his party throughout the later Edwardian period. He was increasingly attracted by tariff reform, and—while publicly loyal to Balfour—he accepted very largely the Chamberlainite prescription of protectionism and socially progressive legislation. He enjoyed a renewed prominence in 1910–11, by virtue of his significant role in the tory election campaigns in January and December 1910, and his very trenchant opposition to the Parliament Bill. He was a convinced die-hard, and was bitterly disappointed by the Lords' ultimate collapse in August 1911. Thereafter disillusionment with parliamentary politics set in. Many of his later letters betray a frustration with the fudges and compromises of political life, and an increasing thirst for action: ‘Let there be murder, or even rape, rather than vague aspiration, and no end achieved. Let something be done—even to DEATH’, he wrote in January 1913 (Mackail and Wyndham, 2.733). His wider cultural and temperamental affinities are illustrated by such declarations, which invite comparison (for example) with the language of advanced Irish nationalist ideologues such as Patrick Pearse. He lost faith in the future, believing that English civilization was threatened with collapse: analogies between England in 1912–13 and Constantinople in 1453 were evoked.

Wyndham once (in January 1910) defined the ‘two poles of political existence’ as being the frontier and the home (Mackail and Wyndham, 2.651). Having fought and lost on different political and geographical frontiers, he turned in his last months to the home. He devoted attention to the family estate (some 4000 acres in Wiltshire) and to the problems and responsibilities of the middling landowner. Public frustrations were balanced by private joys. His beloved son was married (to Diana Lister) on 17 April 1913. His last days were spent in Paris, in the company of Lady Plymouth, and among the bookshops and restaurants of that city. He died suddenly, from a blood clot, around 10 p.m. on 8 June 1913, in his rooms at the Hôtel Lotti on the rue Castiglione, Paris.

Wyndham's reputation remains entrapped within the mire of the devolution controversy. It is possible that, had another ministerial opportunity come his way, he might have combined the bitter lessons supplied by the Irish Office with his genuine political talents to good effect: there is some evidence for believing that this was his own hope. Perhaps, however, the flaws in his judgement were irredeemable. To the end his intellect blossomed with political ideas, but remained largely barren of any wider strategic sense. Margot Asquith, an admittedly unforgiving arbiter, perhaps hit the mark when, in assessing Wyndham, she decreed that ‘an imagination that can work out and foresee the results of big measures is far rarer than the imagination that creates nymphs and moons and passions and patriotism’ (Margot Asquith's diary, October 1904).

Alvin Jackson

Sources J. W. Mackail and G. Wyndham, The life and letters of George Wyndham, 2 vols. (1925) · Letters of George Wyndham, 1877–1913, ed. G. Wyndham, 2 vols. (privately printed, Edinburgh, 1915) · M. Egremont, The cousins: the friendship, opinions and activities of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and George Wyndham (1977) · J. A. Thompson, ‘George Wyndham: toryism and imperialism’, in J. A. Thompson and A. Mejia, Edwardian conservatism: five studies in adaptation (1988) · A. Jackson, The Ulster party: Irish unionists in the House of Commons, 1884–1911 (1989) · A. Gailey, Ireland and the death of kindness: the experience of constructive unionism, 1890–1905 (1987) · E. H. H. Green, The crisis of conservatism: the politics, economics and ideology of the Conservative Party, 1880–1914 (1995) · C. T. Gatty, George Wyndham: recognita (1917) · J. Biggs-Davison, George Wyndham: a study in toryism (1951) · Margot Asquith's diary, priv. coll. · M. Asquith, The autobiography of Margot Asquith, 2 vols. (1920–22) · A good innings: the private papers of Viscount Lee of Fareham, ed. A. Clark (1974) · Eaton Hall, Chester, Wyndham MSS · Burke, Peerage (1937) [Leconfield] · WWW · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1913)

Archives Eaton Hall, Chester, MSS (copies in PRONI) · NRA, family corresp. · NRA, priv. coll., corresp. and papers :: BL, corresp. with Arthur James Balfour, Add. MSS 49803–49806 · BL, letters to G. K. Chesterton, Add. MS 73241, fols. 95–105 · BL, corresp. with Sir Charles Dilke, Add. MSS 43916–43920 · BL, corresp. with Mary Gladstone, Add. MS 46241 · Bodl. Oxf., Selborne MSS, corresp. with Lord Selborne · Glos. RO, letters to Sir Michael Hicks Beach · Herts. ALS, letters mostly to Lady Desborough · Knebworth House, letters to Lord Lytton · NA Scot., corresp. with A. J. Balfour · U. Birm., corresp. with Austen Chamberlain · U. St Andr., corresp. with Wilfrid Ward

Likenesses B. Stone, photograph, 1902, NPG · G. C. Beresford, photographs, 1903, NPG [see illus.] · A. Rodin, bronze bust, 1904, Tate collection · A. Rodin, bronze bust, 1904, Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin · H. Speed, oils, 1914, Dover town hall · Elliott & Fry, photograph, NPG; repro. in Our Conservative and Unionist Statesmen, vol. 2 · B. Partridge, group portrait, caricature, ink drawing, NPG; repro. in Punch (6 May 1903) · Spy [L. Ward], caricature, lithograph, NPG; repro. in VF (20 Sept 1900) · photograph, NPG · plaster cast of death mask, NPG

Wealth at death £205,584 3s. 8d.: probate, 25 June 1913, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Alvin Jackson, ‘Wyndham, George (1863–1913)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/37052, accessed 16 Oct 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Ware, England, 1856 - 1916, London

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Innerleithen, Scotland, 1864 - 1945, London

Blackburn, England, 1838 - 1923, Wimbledon, England