Edward Lear

Lear, Edward (British painter, printmaker, and author, 1812-1888)

Biography:

Lear, Edward (1812–1888), landscape painter and writer, was born on 12 (or possibly 13) May 1812 at Bowman's Lodge, Upper Holloway, London, the twentieth of the twenty-one children of Jeremiah Lear (1757–1833) and Ann (1769–1844), daughter of Edward Skerrett and his wife, Florence. Until 1799 Jeremiah Lear worked as a sugar refiner, but in that year he became a stockbroker. In 1790 he was elected a member of the Fruiterers' Company and a freeman of the City of London, and in 1799 was appointed master. Early biographical writing on Edward Lear's family was based on much misinformation. He himself claimed that his grandfather was Danish: ‘My own [name], as I think you know is really ... LØR, but my Danish grandfather picked off the two dots and pulled out the diagonal line and made the word Lear’ (Later Letters, 18–19). In fact, his father was of English descent; his mother's maternal grandmother was Scottish, and moved to London at some time in the mid-eighteenth century.

Early years and education

According to later family tradition, recorded about 1907, Jeremiah Lear became a bankrupt and was committed to king's bench prison where he remained for four years. No date is given for this, and what evidence there is suggests that there is no truth in it. Jeremiah's name is not found in any surviving record of debtors' prisons, nor is it listed in the London Gazette; indeed he remained a member of the livery of the Fruiterers' Company until his death, which would not have been possible had he been bankrupt. However, there is evidence that at some time in Edward's early childhood his father served a short prison sentence for fraud and debt. Probably at this time, but possibly from his birth, Edward was entrusted to his eldest sister, Ann, twenty-one years older than him, and responsible for his upbringing.

When he was eleven Lear was sent to school for a short period, but apart from this he was educated at home by Ann and his second sister, Sarah. This may have been because of his ill health, for he suffered from short sight, asthma, bronchitis, and, from the age of about five, epilepsy. All his life he was aware of his lack of formal education, although he came to see its possible advantage, writing in 1859:

I am almost thanking God that I was never educated, for it seems to me that 999 of those who are so, expensively and laboriously, have lost all before they arrive at my age—& remain like Swift's Stulbruggs—cut and dry for life, making no use of their earlier=gained treasures:—whereas, I seem to be on the threshold of knowledge. (Noakes, Edward Lear: the Life of a Wanderer, 17)

This image of life as a voyage of discovery informs much of his later ‘nonsense’.An important part of Lear's otherwise inadequate education was his sisters' tuition in drawing and painting, and at fifteen he began to earn his living as an artist. To begin with he relied on teaching, on decorating screens and fans, and on making morbid anatomy drawings. None of his medical work survives, but a commonplace book which he gave to a pupil about 1830 contains some of his decorative work. By 1829, however, he had become an ornithological draughtsman.

Lear as an ornithological draughtsman

Lear served an unofficial apprenticeship with the ornithologist Prideaux Selby who, between 1821 and 1834, published Illustrations of British Ornithology. One engraving in this work, the Great Auk, is known to be based on Lear's drawings. The early part of the nineteenth century was a period of excellence in natural history illustration, encouraged by zoological voyages and the need to identify and classify newly discovered species. The gardens of the Zoological Society of London were opened in 1829, and in June 1830 Lear applied to make drawings of the parrots there. Permission was given at a meeting chaired by the president, Lord Stanley, and Lear devoted the next two years to a publication of his own entitled Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots. This book, published for 175 subscribers in twelve parts between 1830 and 1832, was new in three ways: it was the first devoted to a single family of bird, the first in a large format (imperial folio) in which the illustrations were reproduced by lithography, and the first in which the artist worked direct from nature, using living birds rather than stuffed skins. Lear prepared the lithographic stones himself, and the prints were then hand-coloured. The work received immediate acclaim, the Red and Yellow Maccaw being compared by the naturalist William Swainson to John James Audubon's work. The day after the publication of the first two folios, he was recommended for associate membership of the Linnean Society.

In total Lear produced forty-two lithographs of parrots, but after the appearance of the twelfth part in April 1832 he was forced to abandon the project because his subscribers were so slow in paying that he could no longer afford his printer or colourer. He now had to seek employment, and during the next five years he contributed plates to further works by Prideaux Selby, to Sir William Jardine's series The Naturalist's Library (1825–39), and to works by T. C. Eyton, Thomas Bell, and John Gould, in particular Gould's Birds of Europe (1832–7) and A Monograph of the Ramphastidae, or Family of Toucans (1834). As in the Parrots, he combined precise anatomical accuracy with bold, rhythmic designs and an understanding of the individual personalities of the birds. His work was so fine that he is now considered by many to be England's leading ornithological draughtsman.

One of those who admired Lear's work was Lord Stanley, one of the foremost natural historians of his day, who in 1834 became the thirteenth earl of Derby. He had built a private menagerie at his home at Knowsley, near Liverpool, and was looking for an artist who could make an accurate record of his collection. Lear was invited to take on the project, and between 1831 and 1837 spent long periods at Knowsley, making drawings and watercolours of both animals and birds. A small selection of more than 100 highly finished watercolours was published in 1846 in Gleanings from the Menagerie and Aviary at Knowsley Hall.

For Lear, however, the time at Knowsley produced more than his zoological work, for it was here that he was introduced to one of the earliest published book of limericks, Anecdotes and Adventures of Fifteen Gentlemen (1821?). He had been writing absurd verse since his childhood, but finding himself

in a Country House, where children and mirth abounded ... the greater part of the original drawings and verses for the first ‘Book of Nonsense’ were struck off with a pen, no assistance ever having been given me in any way but that of uproarious delight and welcome at the appearance of every new absurdity. (Lear, introduction to More Nonsense, 1871)

By the mid-1830s Lear was finding that the minutely detailed work required in natural history draughtsmanship was straining his already weak eyesight, and that the damp climate of the north-west was exacerbating his bronchitis and asthma. In these years his interest was turning increasingly to landscape. In 1835 he visited Ireland with Edward Stanley, bishop of Norwich, and his son, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, later dean of Westminster; he returned with a folio of pencil drawings, to which he added during the following year while touring the Lake District. Many of these drawings are characterized by sweeping, chunky lines drawn in soft pencil, demonstrating a release from the close discipline required in his ornithological work. In 1837 Lord Derby and his cousin Robert Hornby offered to send Lear to Rome where he could recover his health and paint landscape. As he left England in July he was turning his back on natural history work; during the rest of his life he produced no more than two or three drawings of birds and animals, although he was later to draw on his knowledge of them in the illustrations to his nonsense.

Roman years

From 1837 to 1848—apart from two extended visits to England—Lear lived in Rome, finding there an international community of artists with whom he spent the happiest period of his life. Among his friends were the Danish painter Wilhelm Marstrand, the English sculptors John Gibson and William Theed, the painters Penry Williams, Thomas Uwins, and Samuel Palmer, and the architect Thomas Wyatt. His routine was to breakfast and dine with others in the artistic community, spending his days drawing in the city or on the Campagna, or working in his studio, experimenting with different media and ways of handling paint. In the summer months he and his friends would explore other parts of Italy, going south to Naples in 1838 and north to Florence the following year, spending the summer months of 1840 closer to Rome, in Subiaco.

In summer 1841 Lear returned to England to publish his first landscape book, Views in Rome and its Environs, with twenty-five lithographic plates and a brief descriptive text. As with the Parrots, this was published for subscribers, a method he used for all his subsequent travel books. His income from painting and teaching was used for day-by-day expenses, but the money he earned from writing was invested in government bonds so that he could one day buy a house of his own.

Lear was back in Rome in December 1841, spending the following summer in Sicily and the Abruzzi. He returned to the Abruzzi the next year, collecting drawings and keeping a detailed journal of his travels. At the end of 1845 he was once more in England, this time staying for more than a year preparing two volumes of his Illustrated Excursions in Italy. The first, published in April 1846, containing thirty lithographic plates and forty vignettes, described his journeys in the Abruzzi; the second, which appeared the following August, contained fifteen lithographic plates and thirteen vignettes, with brief topographical and historical notes. One of his travel companions, Charles Church, nephew of Sir Richard Church, described how Lear believed that it was the combination of words and pictures, rather than pictures alone, that best re-created an image of the places he had visited, an interdependence also characteristic of his limericks. Queen Victoria, one of the subscribers, was so impressed with the work that she invited Lear to give her a series of twelve drawing lessons; two examples of her work done under his tutelage are in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle.

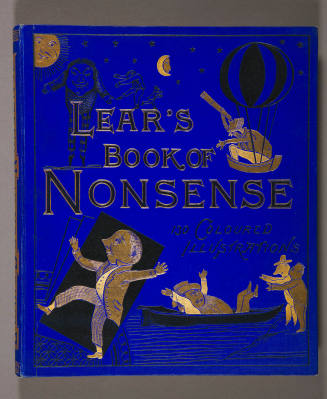

In that same year, 1846, Lear also published A Book of Nonsense, a two-volume collection of seventy-two limerick verses and drawings. Lear himself did not use the word limerick: the first occurrence dates from 1898 in the Oxford English Dictionary and its origins are obscure; he called the verses his ‘Nonsenses’ or his ‘Old Persons’. The first edition did not received much attention; it was not until the third, single-volume edition, published in 1861 and containing 112 verses and drawings, that the limerick swept to popularity. Its appeal to a nineteenth-century children's audience came partly from its simplicity and partly from the benignly anarchic exploits of the characters; Lear's men and women display human foibles and excesses which are accepted without criticism. In other writers' hands the limerick has become sophisticated and often bawdy, almost ceasing to be a verse-form for children, so that some contemporary audiences now find Lear's verses tame. In their time, however, and within the context of children's literature, they were revolutionary and liberating, while his line-drawings, confident and bold, have had a lasting influence on illustration, particularly in the development of the cartoon. Lear published the book himself, selling the rights to Routledge in November 1862 for £125. A Book of Nonsense went through twenty-four editions in Lear's lifetime, and has never been out of print.

In December 1846 Lear returned to Rome. He was now working increasingly in oils, the earliest of which date from 1838 and are freely handled plein-air sketches on paper; his first commissioned oil painting is dated 1840. The paintings of this period measure typically 10 by 15 inches, but in 1847 he began work on the painting Civitella di Subiaco, measuring 50 by 76 inches (Clothworkers' Hall, the City of London). As he turned increasingly to oil painting, the purpose of Lear's watercolours and drawings changed. He now saw them less as works of art in their own right, but rather as the basis for later studio oils and finished watercolours. In works of the mid-1840s we can see the gradual development of his mature watercolour style, which was established by 1847. His method was to make an accurate pencil drawing on the spot, annotating the drawing with descriptive notes which could relate to content (‘rox’, ‘sheep’, ‘fig trees’), to colour (‘dove grey’, ‘dim purple’, ‘bloo ski’), or to form (‘wider apart’, ‘this set of lines is the real proportion’). A friend described him at work:

When we came to a good subject, Lear ... would lift his spectacles, and gaze for several minutes at the scene through a monocular glass he always carried; then, laying down the glass, and adjusting his spectacles, he would put on paper the view before us, mountain range, villages and foreground, with a rapidity and accuracy that inspired me with awestruck admiration. (Later Letters, 23)

Later, following his colour notes, he would spend winter evenings in his studio laying in watercolour washes, and then go over the pencil lines and annotations in sepia ink.In 1847 Lear paid two visits to Naples and Sicily, collecting material for a projected book, Journals of a Landscape Painter in Southern Calabria, &c. (1852). In these as in others of his journeys he would travel on foot, or on horseback, from first light until it grew dark, stopping to draw wherever he saw suitable scenery and settling down each night to write up his journal. Many of the places he visited were uncharted and scarcely known beyond their own communities, and people who travelled with him have described the discomfort and hardship of the conditions, the primitive food and often disagreeable sleeping places, and how he pushed himself physically so that he could not only cover large distances but also produce the work which was one purpose of his journeys. It was thus that he hoped to reach the more remote and most beautiful places which he wanted to see; for a person who had endured a sickly childhood and who continued to suffer from short sight, from chest infections, and from epilepsy, it was an extraordinary achievement.

As Lear went through Calabria he sensed the growing political unrest there, and in April 1848 he decided he must leave Italy. However, before returning to England he decided to spend fifteen months gathering material from which he could later work. He went first via Malta to Corfu, and then on to Greece, where he visited Athens, Marathon, Thermopylae, and Thebes. Prevented from continuing his Greek travels by an outbreak of cholera, he went to Constantinople before returning to Greece, and then on to Albania, journeys described in Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, &c. (1851). By December he was back in Malta, and from there, at the beginning of 1849, he set out for Egypt and Sinai. In February, in Malta once more, he met Franklin Lushington, who was to become his closest friend, and with whom he now explored southern Greece. By July 1849 he was in England, where he planned to settle down and build a reputation as a landscape painter, particularly of remote and unusual places.

The middle years

Until now Lear had been largely self-taught, and he believed that his lack of knowledge, especially of human anatomy, would hamper his artistic ambitions. When in autumn 1849 he received a legacy of £500, he decided to fulfil a long-standing ambition and apply as a student to the Royal Academy Schools. He was now thirty-seven. He had first to pass a qualifying exam: he enrolled at Sass's School of Art, where he prepared drawings for the examiners, and in January 1850 he was accepted. Almost nothing has survived from this period of Lear's life, and we do not know how long he stayed at the academy, nor why he left. It seems that he was there for only a few months, although he later looked back on this brief interlude as a valuable time. Then, in 1852, came the most significant meeting of his painting career, when he was introduced to William Holman Hunt, a leading member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

In his days as a natural history draughtsman Lear had known the importance of working direct from nature, and in this he shared something of the Pre-Raphaelites' approach to painting; he now asked for Hunt's help in overcoming the technical problems he encountered as he worked on large oils. In summer 1852 they rented a farmhouse together at Fairlight, Sussex. Here he was able to watch Hunt painting and to make notes about his methods in ‘Ye booke of Hunte’. Hunt's influence can be most clearly seen in Lear's use of colour as the browns and ochres of his Roman work were replaced by warmer pinks and mauves, and clear greens. That summer he painted Reggio (Tate collection), The Mountains of Thermopylae (Bristol City Art Gallery), and The Quarries of Syracuse (priv. coll.).

The Mountains of Thermopylae was exhibited at the British Institution in spring 1853, and The Quarries of Syracuse at the Royal Academy in 1853, where it was chosen by Frederick Lygon, later sixth Earl Beauchamp, as his Art Union prize. In March that year Lord Derby commissioned Lear to paint Windsor Castle from St Leonards, one of only three oil paintings he did of English scenes. The weather was bad and the light unpredictable, and Lear grumbled about the problems this caused, writing to Holman Hunt: ‘supposing a tree is black one minute—the next it's yellow, and the 3d green: so that were I to finish any one part the whole 8 feet would be all spots—a sort of Leopard Landscape’ (Noakes, Edward Lear: the Life of a Wanderer, 93). Indeed, he was finding the English climate increasingly difficult, for his asthma and bronchitis had returned. In December 1853, to escape the English winter, he sailed for Egypt. By the late spring he was back in London, but in August he left for a walking holiday in Switzerland, a country to whose landscape he did not respond. Back in London, he faced another winter of rain and semi-darkness. His lungs were now so bad that he could scarcely go out, and he realized that he could not settle permanently in England. Franklin Lushington had recently been appointed judge at the supreme court of justice in the Ionian Islands, and so Lear decided to join him and make a winter home in Corfu. They sailed from Dover in November 1854.

The issue of Lear's supposed homosexuality has been much discussed. He never married, but evidence suggests that this was because of his epilepsy; he believed it to be inherited, and that he might pass it on to his own children. However, he longed for children of his own, and in 1867 he contemplated proposing to Augusta (Gussie) Bethell, daughter of the lord chancellor, who would almost certainly have accepted him. But at the last minute he drew back, probably believing that once she knew of his illness she would refuse to marry him. Although his childhood companions were aware of his illness, no adult friend ever realized that he was an epileptic. The loneliness which maintaining this secret forced upon him is an important key to Lear's personality, the source both of his lonely unhappiness and of much of his nonsense. His closest friendships were with men, and for a time he had a powerful, but unreciprocated, emotional involvement with Franklin Lushington, but beyond this there is no evidence to suggest that he was a homosexual. Despite his loneliness, and his frequent bouts of debilitating depression, until the last and loneliest years of his life when he became irritable and cantankerous, more especially to strangers, Lear was a sought-after and convivial companion, with a wide circle of acquaintance and many real friends who remained trusted and supportive even in the final years of his life. Children responded to his tall, shambling, bearded, bespectacled figure with warmth and happiness, and he treated them with humorous understanding and respect.

In August 1856 Lear crossed over from Corfu to Greece and went on to Mount Athos, but while he was there his servant, Giorgio Kokali, was taken ill with malaria. Lear had to stay close to the monastery where Kokali was being looked after, which meant that he could spend more time than usual on individual drawings, and on 9 and 10 September 1856 he drew one of his finest watercolours, The Monastery of St Paul (priv. coll.). After a second winter in Corfu he returned via Venice to London. In that year, 1857, The Quarries of Syracuse was exhibited in the International Exhibition in Manchester. The following March he went from Corfu to revisit Egypt and Palestine, travelling on to Petra and Lebanon. Lushington had now resigned his post, and so Lear decided that the following winter he would return to Rome. Within days he realized that it was a mistake: both he and the city had changed. He had taken rooms for three years, but after a second winter he decided not to return. Instead he spent the winter of 1860–61 in England; his sister Ann was unwell and he wanted to be near her, and he planned to work on a large painting of the cedars of Lebanon.

Although he had made a number of studies of the cedars during his trip to Lebanon in 1858, Lear wanted to work from living trees: these he found at Oatlands Park Hotel in Weybridge. In March Ann died, and his sense of loneliness deepened, but work on the 9 foot painting progressed well, and it was completed in May 1861. The Cedars of Lebanon was his largest and most important painting, and he awaited the critical response to it anxiously. In August it was exhibited in Liverpool, where it was highly praised, but in the following May, when it was shown in the Great International Exhibition in South Kensington, it was hung so high that it could scarcely be seen. The influential Tom Taylor, reviewing the exhibition in The Times, dismissed the painter as being no more than a mirror of the scene where he should have recreated what he saw and set upon it the seal of his own mind, a charge of lack of poetic feeling frequently levelled against topographical painting at that time. This was something to which Lear was particularly sensitive, delighting in Arthur Stanley's description of him as ‘the Painter of Topographical Poetry’ (Noakes, Edward Lear, 1812–1888, 132), and he was both mortified and angered by what he saw as uninformed and unjust criticism.

Lear had priced The Cedars at 700 guineas, but after its dismissal by the critics it failed to sell. ‘What I do with the Cedars I do not know’, he wrote a year later:

probably make a great coat of them. To a philosopher, the fate of a picture so well thought of & containing such high qualities, is funny enough:—for the act of two Royal Academicians in hanging it high, condemn it first,—& 2ndly the cold blooded criticism of Tom Taylor in the Times, quasi=approving of its position, stamps the poor canvass into oblivion still more & I fear, without remedy. (Noakes, The Painter Edward Lear, 77)

Five years later it was still unsold, and he wrote in despair:

sometimes I consider as to the wit of taking my Cedars out of its frame & putting round it a border of rose colored velvet,—embellished with a fringe of yellow worsted with black spots, to protypify the possible proximate propinquity of predatorial panthers,—& then selling the whole for floorcloth by auction. (Noakes, Edward Lear: the Life of a Wanderer, 178)

It was eventually bought in 1867 for 200 guineas; its present whereabouts is unknown. From the time of Lear's return to England in 1849 his paintings had been commanding increasing prices and finding ready buyers. The failure of this work was the turning point of his career, and he was to live the rest of his life in professional isolation, disappointment, and financial insecurity.

In summer 1861 Lear travelled to Florence to make a painting for one of his most consistent patrons, Frances, Lady Waldegrave, later the wife of his close friend Chichester Fortescue. Lear spent the two following winters in Corfu, and it was here in November 1862 that he began the first of a series of watercolours which lastingly damaged his reputation, but which brought in a steady but undramatic income: he called these his Tyrants. First, he sorted through the drawings he had done on his travels, selecting sixty on which to base studio watercolours. Then he prepared sixty sheets of paper and, working on them in two groups, he drew pencil outlines of thirty views, which he spread out around his studio. He then moved from one to the next, laying in blue washes, then red, then yellow, and so on, until he had thirty completed works. He then repeated this process with the second group. ‘For the present I have done with oil painting, & have collapsed into degradation & small 10 & 12 Guinea drawings calculated to attract the attention of small Capitalists’ (Noakes, Edward Lear: the Life of a Wanderer, 156). When they were finished he ordered sixty frames, and by mid-February he was ready to exhibit them. The small capitalists responded, for within days many had sold and he could once more pay his bills. Between 1862 and 1884, Lear produced nearly one thousand Tyrants. The income from their sale was essential, but they did his reputation little good. As a friend later remarked: ‘if he had exercised a judicious selection of his exhibition pieces, instead of hanging good, bad and indifferent pictures together ... his value at the time would have been considerably enhanced’ (Malcolm, 118).

With the first set of Tyrants finished, Lear turned his mind to other possible sources of income. The Ionian Islands had been ceded to the Greeks in 1863, and before leaving he toured the islands in preparation for Views in the Seven Ionian Islands, which he published in December 1863. In this he returned to the format of the earlier books; there were twenty lithographic plates, each with a short descriptive text, but no personal account of his journey. In April 1864 he left Corfu, and set out to explore Crete. By June he was back in England. With the failure of his artistic ambition, he began to consider living permanently abroad. The savings from his publications, and a small legacy from Ann, meant that he could afford to build a house where he would live quietly and paint. He needed now to find a suitable place: in winter 1864–5 he was in Nice, and after spending a month working on a group of 240 Tyrants, he set out with Giorgio Kokali to walk along the corniche. In blustery winter weather he crossed into Italy, passing through San Remo, his first visit to the place where he spent the last seventeen years of his life.

In the following winter Lear went via Venice to Malta, but he found it a dull, unstimulating place to winter. A year later he was in Egypt, keeping a detailed diary of his voyage down the Nile, one of several which he planned, but failed, to publish. In 1867–8 he wintered in Cannes, wondering if France might be the best place to settle, and from there he visited Corsica, the subject of his last, and least successful, travel book, Journal of a Landscape Painter in Corsica, which was published in 1870.

In many ways these were rootless and dispiriting years, and yet it was during the latter half of the 1850s and throughout the 1860s, when Lear had given up hope of becoming a sought-after painter, that he produced his finest watercolours. He had achieved a masterly control of his medium, combining powerful composition with strong line and a fluid freedom in the handling of paint which would establish him as one of the great English watercolour painters. But—living in a time when an artist's reputation was made in mixed exhibitions of large oils—he regarded these small masterpieces as no more than the basis of his studio work. Then, in the late 1860s, Lear discovered a new means of expression. The success of the third edition of A Book of Nonsense (1861) had made his a household name. In February 1865 he wrote a prose story, the ‘History of the Seven Families of the Lake Pipple-Popple’, for the children of Lord and Lady Fitzwilliam, who were wintering close to him in Cannes. Two years later he composed ‘The Story of the Four Little Children who Went Round the World’ for Gussie Bethell's nephews and nieces. Then, in December 1867, when Janet, the six-year-old daughter of his friend John Addington Symonds, was ill in bed, Lear wrote and illustrated for her a poem called ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’: this was the first of his nonsense songs which can be positively dated.

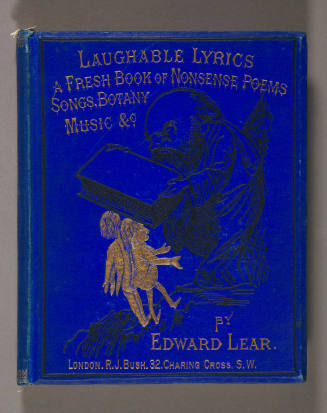

It is interesting to speculate whether, if Lear had achieved his ambition as a painter, he would have written the songs which were composed over the next nine years, between December 1867 and August 1876, and which are the most enduring of his nonsense creations. Some are simple nursery songs; some are tales of misfits who travel together to places where their oddities no longer matter and where they can dance and sing joyously together. Others are poems of risk and adventure, loneliness and rejection. Be bold, he is saying to the children, and dare to leave behind the safe world you know, for as you go in search of distant places you may discover majestic beauties and new freedoms which the faint-hearted cannot even imagine. But in the songs of the later 1870s he speaks also of the loneliness which can await those who find themselves abandoned on some distant shore. He published two nonsense books in quick succession, Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets (1871), which contained among others ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’, ‘The Duck and the Kangaroo’, ‘The Daddy Long-Legs and the Fly’, and ‘The Jumblies’, and More Nonsense (1872), a book of 100 new limericks.

Later nonsense writing, and the return to Italy

Meanwhile, Lear decided that southern France was too fashionable and too expensive, and instead he began to search for land across the border in Italy. At the end of 1869 he found a plot in San Remo, a place ‘Neither too much in, nor altogether out of the world’ (Noakes, Edward Lear: the Life of a Wanderer, 204). He designed the house, which he called Villa Emily, so that he would have a large first-floor studio looking out over olive groves towards the sea, and a ground-floor exhibition room where he could have a permanent exhibition of his work to which people could come on open days. He moved in during March 1871 and, once he was settled, his thoughts turned to a project he had had in mind since 1851, a series of drawings for Alfred Tennyson's poems. He had met Tennyson that year, and shortly after their meeting had sent Alfred and his new wife, Emily, a copy of his Albania journal as a wedding present; in response to this, Tennyson had written the poem ‘To E.L. on his Travels in Greece’. Later, as Lear found Alfred increasingly overbearing, the friendship between them cooled, but he remained devoted to Emily, who understood perhaps more than anyone the loneliness and sadness of his life. He set a number of Tennyson's poems to music, publishing some of them between 1853 and 1860. These settings are no more than pleasant Victorian ballads, but Alfred was delighted by them, saying that ‘they seem to throw a diaphanous veil over the words—nothing more’ (C. Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson, 1949, 441). Lear knew that Tennyson disliked his work being illustrated, and he cautiously disclaimed his drawings as illustrations, suggesting that ‘“Painting=sympathizations” would be better if the