Rudyard Kipling

LC name authority rec. n79103792

LC Heading: Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936

Biography:

Kipling, (Joseph) Rudyard (1865–1936), writer and poet, was born in Bombay, India, on 30 December 1865, the son of John Lockwood Kipling (1837–1911), professor of architectural sculpture in the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art in Bombay, and his wife, Alice Kipling [see under Macdonald sisters]. The name Joseph (never used) was family tradition, elder sons being named Joseph or John in alternation; ‘Rudyard’ came from Lake Rudyard in Staffordshire, where his parents had first met. Both his father and his mother were the children of Methodist ministers, and both quietly rebelled against their evangelical origins. Kipling was brought up in indifference to organized religion; although he always believed in the reality of the spiritual, he never held any religious doctrine. His childish impressions of Muslim, Hindu, and Parsi—he recalled ‘little Hindu temples’ with ‘dimly-seen, friendly Gods’ (Kipling, Something of Myself, chap. 1)—made him more sympathetic to those forms than to the charmless protestantism he afterwards encountered in England.

Early years and education

In 1871 the Kipling family, now including his younger sister Alice (always called Trix), Rudyard's only sibling, returned to England on leave. On their return to India the parents left their children with people in Southsea, now part of Portsmouth, who had advertised their services in caring for the children of English parents in India. It was a usual practice for the children of the English in India to be thus separated from their parents, but Rudyard and his sister were not prepared for the event. ‘We had had no preparation or explanation’, Kipling's sister wrote; ‘it was like a double death, or rather, like an avalanche that had swept away everything happy and familiar’ (Fleming, 171). Nor is it known why the parents chose to put them in the hands of paid guardians rather than with one or more members of Alice Kipling's family. One sister was married to Alfred Baldwin, a prosperous manufacturer: their child, about the same age as Rudyard, was Stanley Baldwin, afterwards prime minister; another sister had married Sir Edward Burne-Jones, the painter; a third sister had married Sir Edward Poynter, who became president of the Royal Academy. By 1871 all of these families would have been able and willing to receive the Kipling children.

Instead they went to Southsea, to a house now notorious as the House of Desolation (so-called in Kipling's ‘Baa baa, black sheep’). Kipling was not yet six years old; Trix was three. Here he attended ‘a terrible little day-school’ (Kipling, Something of Myself, chap. 1). The woman who cared for them, Mrs Pryse Agar Holloway, is, in Kipling's account of her as Aunty Rosa, a monster. Deliberately cruel and unjust, she tries to set sister against brother, systematically humiliates the young Kipling, allows her son to terrorize him mentally and physically, and denies him simple pleasures. She also introduces a Calvinistic protestantism into Kipling's experience: ‘I had never heard of Hell, so I was introduced to it in all its terrors’ (ibid.). He took refuge in reading. One of his punishments was to be compelled to read devotional literature: in this way he acquired a mastery of biblical phrase and image. The Kipling children remained with Mrs Holloway for five and a half years: towards the end of that time, Kipling's eyesight began to fail, and to his other miseries were added ‘the nameless terrors of broad daylight that were only coats on pegs after all’ (ibid.). Kipling's mother returned from India in April 1877, and for the rest of the year her children lived with her. At the beginning of the next year Kipling went off to public school; Trix returned to the care of Mrs Holloway.

The truth of Kipling's description of his childhood has been doubted: Mrs Holloway was not cruel but misunderstood by a spoiled, preternaturally imaginative child; ‘Baa baa, black sheep’ is fiction, not autobiography; or, if autobiography, then shamelessly self-indulgent. And how can one explain Trix's return to Southsea? We cannot now know the facts. The effects of Kipling's abandonment in the House of Desolation upon his psyche, and, in turn, upon his works, continues to be at the centre of biographical and interpretive arguments. Kipling's own judgement was that his sufferings ‘drained me of any capacity for real, personal hate for the rest of my days’, a conclusion not generally agreed with. He also thought that the experience contributed to the growth of the artist: ‘it demanded constant wariness, the habit of observation, and attendance on moods and tempers’ (Kipling, Something of Myself, chap. 1). If he blamed his parents, that did not appear in his behaviour towards them; he was not merely dutiful and loving but seems genuinely to have admired them both.

Kipling believed that what ‘saved’ him during his Southsea ordeal was an annual visit to his aunt, Georgiana Burne-Jones, at The Grange, in Fulham, London, where he ‘possessed a paradise’ of ‘love and affection’ (Kipling, Something of Myself, chap. 1). He was also much interested at The Grange in the example of his uncle at work and by Burne-Jones's conversations with such friends as William Morris, interests that Kipling's own artist father must have helped to encourage. We know little about Kipling's imaginative development until rather late in his school-days, but the impact of Burne-Jones and of the group to which he belonged, devoted to the highest standards of craftsmanship and to an unembarrassed worship of beauty, must be allowed to have had an important part in forming Kipling.

At the beginning of 1878 Kipling was sent to the United Services College at Westward Ho!, Bideford, north Devon, founded in 1874 by army officers in order to provide an affordable public school for their sons. Most of the students had the army as their goal. The headmaster, Cormell Price, an Oxford graduate, was a friend from early days of both Burne-Jones and of Kipling's mother. The new, raw, impoverished school was an unlikely place, but, after a long period of unhappiness following his entry, Kipling thrived there. For this happy result he always credited Price, whose virtues he magnified in the figure of the Head in Stalky & Co.; more practically, he remained devoted to Price to the end of his days, helping him financially in his retirement and, after Price's death, acting as a trustee for Price's son. It is now impossible to see Kipling's school-days uncoloured by Stalky & Co. (1899), Kipling's fictional version of his life at Westward Ho! The bare facts that we have are often mildly at variance with Stalky, but the energy of the Stalky version overwhelms all attempts to correct the record. One may safely say that Kipling did make friends with Lionel Dunsterville (Stalky), with G. C. Beresford (M'Turk), was himself a recognizable original for Beetle, and was impressed more than he knew by the example of William Carr Crofts (King) and his passion for Latin literature. He admired Price, was given the run of Price's library, and edited the school paper, revived by Price for the express purpose of allowing Kipling to edit it. He also began to experiment in poetry, the form of literature he loved first and best. The extent and variety of Kipling's precocious exercises in poetry have been made clear in Andrew Rutherford's edition, Early Verse by Rudyard Kipling (1986), which includes fluent imitations of popular ballads, Pope, Keats, Browning, and Swinburne, among many others. In 1881 his parents privately printed a selection of this work under the title Schoolboy Lyrics. Though it was produced without Kipling's knowledge, and though he was embarrassed by it then and afterwards, the book is technically Kipling's first and is now one of the rarissima in his bibliography.

Despite the army flavour of the United Services College, Kipling's interests at the time seem to have been almost wholly literary. His school-days ended in May 1882; an indifferent school record and his parents' lack of means put Oxford and Cambridge out of the question. For a brief time Kipling flirted with the idea of medicine (an admiration for doctors and an interest in the art of healing always remained with him). Kipling's parents were both occasional contributors to the Civil and Military Gazette (CMG), published in Lahore, where, in 1875, John Lockwood Kipling had been appointed head of both the newly founded Mayo School of Art and of the Lahore Museum. Through his parents' influence with the proprietors of the paper Kipling was offered a position as sub-editor and went to India in September 1882, arriving in Lahore towards the end of October. For the next six years and four months Kipling was to work uninterruptedly on newspapers in India.

Journalist in India

Though he was at first kept to routine editorial work, gradually Kipling began to write more, and more variously, for the paper—verse, an irregular column of local gossip, summaries of official reports, news paragraphs, and the like. In March 1884 he was sent to Patiala to report a state visit of the viceroy, and his success in this trial was such that from that point on the flow of his writing in the CMG is unchecked. The overflow found other outlets. In 1884 he and his sister published a collection of verses titled Echoes, exhibiting English life in India in the form of parodies of standard poets: Kipling's knowledge of American literature appears in his parodies of Emerson, Longfellow, and Joaquin Miller. For Christmas 1885 all four Kiplings published an annual called Quartette, containing such distinguished early work as ‘The Strange Ride of Morrowbie Jukes’ and ‘The Phantom 'Rickshaw’. These exhibit the remarkably precocious maturity—Kipling was not yet twenty when they were written—that prompted Henry James to write of Kipling as a youth who ‘has stolen the formidable mask of maturity and rushes about making people jump with the deep sounds, the sportive exaggerations of tone, that issue from its painted lips’ (James).

In 1886 Kipling published Departmental Ditties, lightly satirical verses about official life in India reprinted from the CMG. This, which Kipling always regarded as his first book, had a great success among the community it satirized. It also drew a brief, friendly notice from Andrew Lang in London, Kipling's first recognition in England.

As a journalist, Kipling was neither a civil servant nor a military officer, but could move freely among the different levels of Lahore society. The capital of the Punjab, Lahore abounded in high officials. It was also an army post, and Kipling discovered a new pleasure in observing and making friends with the officers and men of the British troops stationed at Fort Lahore and at Mian Mir, the nearby barracks. He wandered through the streets of Lahore at night, and though he claimed afterwards to have seen perhaps more of native life than in fact he did, he certainly paid that life more sympathetic attention than usually allowed to the English in India. In 1886, while still under age, he joined the masonic lodge Hope and Perseverance of Lahore, and was active in its affairs while he remained in Lahore. The prominence of masonic lore and masonic symbolism in Kipling's work from this time on is a recognized critical topic, as is the attraction to fraternal or exclusive organizations (for example Stalky & Co., Soldiers Three, the Seonee Pack, the Janeites) witnessed by his membership in the freemasons.

In November 1887 Kipling, now recognized as one of the best journalists in India, was transferred by his proprietors to their other, larger paper, The Pioneer, of Allahabad. Lahore had been Muslim; Allahabad, on the banks of the Ganges, was Hindu. Kipling made no secret of his preference for the Muslim element in India, a preference only reinforced by his residence in Allahabad. His work now mostly consisted in providing verse or fiction for his paper, or in carrying out special assignments. Kipling now travelled round India to produce the articles collected in From Sea to Sea (1900) as ‘Letters of marque’, ‘The city of dreadful night’, ‘Among the railway folk’, and ‘The Giridh coal-fields’, articles that combined the oldest India with the newest one of railways, factories, and other works of the raj. Before he went to Allahabad Kipling had been publishing a series of stories in the CMG under the title ‘Plain Tales from the Hills’, the hills being the high foothills of the Himalayas at Simla, the summer capital of British India where Kipling had spent several of his summer leaves. Simla society, with its gossip, jealousies, amours, and other amusements, gave Kipling his material; the ‘Plain Tales’ were a sort of ‘Departmental Ditties’ converted to prose and somewhat more serious. In book form Plain Tales from the Hills (1888) was an immediate hit.

Early in 1888 Kipling's proprietors, confident of their star young employee's productive power, made him editor of a new weekly supplement to The Pioneer called the Week's News, which provided a page to be filled each week with a new fiction. Kipling now began to pour out the stories that, collected and reprinted in the series of paperbacks called the Railway Library, made his name in India and, soon enough, in England and America as well. Carrying modestly anonymous illustrated covers drawn by John Lockwood Kipling, the series of volumes—the product of a single year—included Soldiers Three (1888), The Story of the Gadsbys (1888), In Black and White (1889), Under the Deodars (1889), The Phantom 'Rickshaw (1889), and Wee Willie Winkie (1889). This prodigality was no fluke. Kipling, throughout his career, always found more opportunities for fiction and poetry bidding for his attention than he could possibly respond to. As he wrote to his sister late in life, the ideas kept ‘rising in the head ... one behind the other’ (Kipling, letter, 8–10 March 1931). And so it always was.

Return to England and early fame

India was now too small for Kipling. Before the end of 1888 he had determined to return to England to try his fortunes as a writer, and early in March 1889 he sailed from Calcutta for London. He reversed the usual route and travelled to Singapore, China, and Japan, before crossing the north Pacific to San Francisco and then across the United States. He sent back stories at every stage of his journey to The Pioneer, later collected in From Sea to Sea. His companions on the voyage were Professor and Mrs Alex Hill, friends from Allahabad. Mrs Hill, an American, was more than an ordinary friend; she had been confidante and muse to Kipling and had exercised a strong attraction upon him during the entire period of his life in Allahabad. While staying with her family in Pennsylvania towards the end of his journey Kipling became engaged to her sister, Caroline Taylor. The engagement did not long survive Kipling's return to England, but it is a curious episode in his emotional life, apparently having more to do with his feelings towards Mrs Hill than towards her sister. The articles that Kipling sent back to India during his travels across the Pacific and the Atlantic were typical of his youthful manner—enthusiastic, unrestrained, sometimes tactless, but always striking and vivid. One of them reports his pilgrimage to the greatly admired Mark Twain in upstate New York. On his travels across the American continent Kipling saw reason to confirm his already formed opinion of the United States as an attractive but violent and lawless community. Did he in fact see a man shot dead in a Chinese gambling-hell in San Francisco? No matter. He wrote as though he had. Americans were a people ‘without the Law’.

Kipling at last arrived in England early in October 1889, took chambers in London, and almost at once entered into his fame. Some editors already knew his work, or had heard of it; others needed only to see some of it to bid eagerly for it. He had no interval of starving in a garret (nor did he ever have to worry about money) but rather had to defend himself against demands he could not possibly meet. He encountered this sudden success warily: publishers were rascals; editors wanted only to skim one's brains; the public cared only for the latest celebrity, no sooner exalted than cast aside. Kipling was determined that he would have nothing to do with this. He put his literary affairs in the hands of an agent and for the rest of his life had no direct dealings with publishers. He would be identified with no literary clique, and he sought to avoid publicity. He did join the Savile Club, and was gratified by the friendship of such men as Andrew Lang, H. Rider Haggard, Edmund Gosse, Thomas Hardy, and Sir Walter Besant. In the course of his life Kipling would have many other literary and artistic acquaintances—Henry James, for example, whose achievement Kipling fully appreciated—but he did not seek them out, and always seemed to prefer public men or men of action, Theodore Roosevelt or Dr Jameson, for example. A more agreeable side of this stand-offishness was Kipling's resolve never to criticize or to comment in print on the work of his fellow authors, a resolve strictly maintained throughout his life, despite the fact that his private comments and indirect published remarks show him to have been an extremely shrewd judge.

Kipling's return to London at the end of 1889 began a quarter-century of unbroken production of literary work of the highest originality, distinction, and popularity: three novels, four volumes of poems, twelve volumes of stories, including such unclassifiable inventions as the Jungle Books and Puck of Pook's Hill, four volumes of essays and sketches, and much miscellaneous writing, some of it uncollected, came from his pen between 1890 and 1914. It would be difficult to match this record for sustained quantity, variety, and quality in the whole of English literature. Kipling's fame grew immense, and was matched by his sales, which were measured in the millions world-wide and which were never much affected by the chops and changes in his critical reputation.

Kipling's first impact upon a wide public was as the poet of British India, including the British tommy, a subject quite new to most readers. It is likely that, despite all Kipling's varied later work, the Indian association will always come first whenever his name is mentioned. Kipling's ‘imperialism’ did not crystallize until after his return to England, when he saw that the realities of the empire at work were unknown to the people at home; thereafter it was a part of his artistic purpose to give a voice to the administrators, the soldiers, and their women who made the empire function. Two ideas running through his work arise in connection with his imagination of India but are not confined to it: the notion of a ‘law’ that must be obeyed as the condition of human society, and the notion that what we do is set for us by the conditions of our situation—by ‘history’. Thus Kipling's ‘imperialists’ are not swashbuckling conquistadores but men whose work has been laid upon them: in this sense they do not differ from the English at home or from any other historical community. Another theme, not yet much apparent but always present, was that of the occult—of things beyond the grasp of reason but nevertheless powerful. Kipling the man, as opposed to the artist, was hostile to such ideas: he held that his sister's long periods of mental disturbance were partly caused by the ‘soul-destroying business of “spiritualism”’ (Kipling, letter, 3 June 1927). Nevertheless, many stories, from the early ‘Phantom 'Rickshaw’ to the late ‘Wish House’, show how strongly Kipling the artist was drawn in that direction. Another marked interest was in giving to every kind of creature a voice—from the dialect of Soldiers Three to the canine speech of Thy Servant a Dog (1930): in doing this, Kipling displays one of the largest vocabularies in English literature.

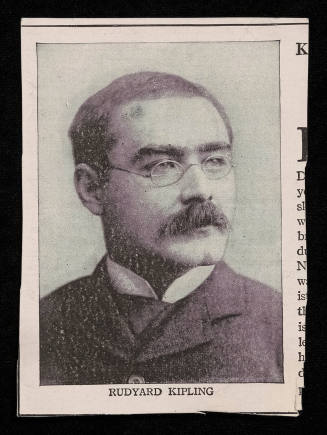

When Kipling burst upon the public in 1889 he was just about to turn twenty-four. A short, slight man, his notable features were bushy dark eyebrows, penetrating bright blue eyes behind thick spectacles, a full, bristling moustache, and a prominent cleft chin. These made him an easy mark for the caricaturists, the most formidable of them Max Beerbohm, upon whom Kipling long exercised the fascination of abomination. Kipling was beginning to lose his hair at the time he left India, and by the end of the 1890s he was bald on top, a strong contrast to the bushy eyebrows and moustache. He was inordinately fond of tobacco, as was his father, and enjoyed it in cigarettes, cigars, and pipes. Otherwise he was temperate in his habits, though he knew and enjoyed good food and wine until illness denied it to him (George Saintsbury's Notes on a Cellar-Book is dedicated to Kipling). Drunkenness he abhorred. His defective eyesight is supposed to have adversely affected his athletic ability, but he at least attempted to play polo and tennis in India. Fishing especially appealed to him, and he seems to have been at least a competent fly-fisherman. His daughter remembered him as ‘compact of neatness and energy. He never fumbled, and his gestures were alway expressive’ (Carrington, 517).

Kipling was no ordinary reader, but consumed books of every kind, rapidly and in large numbers. His years of journalism had taught him that no subject was without interest, and he enjoyed forms of print not usually regarded as attractive, including blue books (official government reports). Although a literary traditionalist, who knew English literature thoroughly and French literature well, and who delighted in the Latin of Horace, Kipling read widely in current literature as a matter of course. He claimed to be unmusical, though he was acutely sensitive to metrical form. Painting interested him, as one would expect in a man whose father and two of whose uncles were professional artists, and his own work in illustrating the Just So Stories shows that he had a distinct gift. But he does not seem to have paid any special attention to the graphic arts.

Within the first two years of his entering the London literary life, Kipling produced The Light that Failed (1890), Life's Handicap (1891), The Naulahka (1892, in collaboration with Wolcott Balestier), Barrack-Room Ballads (1892), and most of the stories collected in Many Inventions (1893); to this one may add Plain Tales from the Hills and the six volumes of the Railway Library, now reprinted from the Indian editions for the British and American public. Readers who had not heard of Kipling at the beginning of 1890 could have a whole shelf of Kipling by the end of 1892. Kipling several times broke down under the strain of his work, a strain complicated by the confusions of his personal life. The engagement to Caroline Taylor ended early in 1890; at the same time he encountered again a woman named Flo Garrard, to whom he had imagined himself engaged when he left England for India and who contributed to the figure of Maisie in The Light that Failed. Kipling renewed his pursuit of Flo Garrard for a time, unsuccessfully.

Marriage and residence in the United States

In August 1891 Kipling set out on a voyage around the southern hemisphere, making his first visit to South Africa and his only visits to New Zealand and Australia. In December he reached Lahore, where he learned of the sudden death of his friend, the American Wolcott Balestier, with whom he had collaborated on the romance called The Naulahka, and to whom Barrack-Room Ballads was dedicated. Kipling immediately left Lahore (he was never to return to India), arrived in London early in January, and at once married Balestier's sister, Caroline (1862–1939), by special licence on 18 January 1892. This curious story has never been elucidated, and hardly any record survives of the early history of the Balestier–Kipling relation. It has been suggested that the attraction between Wolcott Balestier and Kipling was homosexual, but, if so, it is hard to see how that explains Kipling's marriage to the sister. Kipling and Caroline Balestier had been known to each other since 1890 and there is some reason to think that there had been an understanding between them before Kipling set off on his voyage. Many, but by no means all, of those who knew the Kiplings did not like Mrs Kipling, finding her dictatorial, selfish, and ill-spirited. Whatever others thought, Rudyard and Caroline appear to have been happy in each other and maintained a steady mutual respect and affection through forty-four years of marriage.

They travelled as far as Japan on their wedding-journey, when the failure of Kipling's bank drove them back to Vermont, where Mrs Kipling's family then lived. There they bought property near Brattleboro, built a house, and began a family: Josephine, their first child, was born in 1893, Elsie, their second, in 1896. Kipling flourished in the isolation of Vermont in the citadel of his own house: here he wrote The Jungle Book (1894), The Second Jungle Book (1895), Captains Courageous (1897), and most of the stories collected in The Day's Work (1898); he also published the second collection of his poems, The Seven Seas (1896), mostly written between 1892 and 1896. He hoped in time to write stories about America (Captains Courageous is a very restricted venture); in the meantime, the subject of India grew steadily less prominent in his work. On his fairly frequent expeditions out of Vermont, Kipling made the acquaintance of a wide range of distinguished Americans, including Charles Eliot Norton, Theodore Roosevelt, Samuel Langley, Henry Adams, and Brander Matthews. Nevertheless, the American episode ended badly. Kipling was much troubled by the anti-English spirit aroused by a border dispute between Britain and Venezuela at the end of 1895. In 1896 he quarrelled with his brother-in-law, Beatty Balestier, had him arrested for threatened violence, and was humiliated in a courtroom hearing. In September the Kiplings left Vermont for England.

After a false start in Devon they settled at The Elms, Rottingdean, Sussex, where the Burne-Joneses also had a house. Here, in August 1897, the Kiplings' last child and only son, John, was born. Early in 1899 Kipling, with some idea of repairing his American relations, took his family to New York; there he and the children fell ill. Josephine and Kipling developed pneumonia, and for many days in February and March Kipling's struggle against death was headline news across the United States. At the crisis of Kipling's illness, Josephine died, unknown to him. Not until June was Kipling strong enough to return to England, never to visit the United States again.

While recuperating Kipling put together the articles in From Sea to Sea (2 vols., 1900), compelled by pirated American editions thus to reprint early work that he would otherwise have left in obscurity. About this time Kipling fought several cases in the American courts, always unsuccessfully, against what he regarded as piratical publishing. Stalky & Co. appeared at the end of 1899; Kim, which Kipling had matured for nearly a decade, in 1901; the Just So Stories, begun as stories for Josephine, were published serially from 1897 and collected in 1902. Kipling called Kim ‘a labour of great love’ and thought it ‘a bit more wise and temperate than much of my stuff’ (15 Jan 1900, Letters, 3.11). It is, effectively, his farewell to India, in the form of a romance that has pleased even many of those not disposed to like Kipling's work.

South Africa and England

After his serious illness Kipling was advised to spend his winters out of England. In the winter of 1898 he had taken his family to South Africa, where he had met Rhodes and Milner and had travelled as far as Bulawayo. He now determined to make South Africa his regular winter home, a decision that coincided with the outbreak of the South African War.

From this time until he abandoned it in 1908, South Africa played a large part in Kipling's life. His admiration for Rhodes, Milner, and Jameson was unqualified. In South Africa in the spring of 1900 he was delighted to serve briefly, at Lord Roberts's invitation, on the staff of a paper called The Friend, got out for the troops at Bloemfontein. Two of the journalists he met on the staff, Perceval Landon and H. A. Gwynne, remained lifelong friends. Kipling's one experience of live battle was outside Bloemfontein in March 1900.

South Africa and the war reinvigorated Kipling: ‘I'm glad I didn't die last year’, he wrote from Cape Town (7 April 1900, Letters, 2.14). The experience did him no good with his public, however. The British unpreparedness exposed by the early Boer successes persuaded Kipling and many others that the country needed fresh discipline. Kipling now took up the theme of preparedness through compulsory military service, and his hectoring of the British public on this subject (for example in ‘The Islanders’) alienated many readers. The poems of The Five Nations (1903) and the stories of Traffics and Discoveries (1904) are the main literary memorials of Kipling's South African adventure, but they are not only that. Two stories in the collection—‘They’ and ‘Mrs. Bathurst’—embody a delicacy of suggestion and a richness of allusion greater, perhaps, than what had been seen in Kipling's work before. They mark out the line of development leading to the great stories of Kipling's last decade. The contrast from this point on in Kipling's life between the stridency of his political views and the wide sympathy of his work shows how little we understand the relations of politics to literature. Unfortunately, much of Kipling's work continues to be judged through a simple connection of the two.

When Kipling and his family returned to Cape Town at the end of 1900 they lived in a house called The Woolsack, built for them by Rhodes in the grounds of his Cape Town estate. Here Kipling and his wife consulted with Rhodes about his scheme for international scholarships at Oxford (Kipling was later a Rhodes trustee), and here Kipling dreamed about a South African future after Rhodes's ideas, in which a dominant English population would create a golden peace and prosperity. The dreams were shattered by the great Liberal victory in Britain in 1906, followed by the return to responsible government of the Boers. Kipling saw this as the destruction of all that Rhodes had worked for; after a last stay in the winter of 1908 he left, bitterly disappointed, never to return to South Africa.

Kipling now turned to English history on the widest possible basis. In 1902 he bought a seventeenth-century house called Bateman's, Burwash, Sussex, where he spent the rest of his life, and where he made himself master of the traditions and topography of the region (the house is now a Kipling memorial owned by the National Trust). He was helped in this by the advent of automobile travel, of which he was an early and enthusiastic champion. As he wrote in April 1904,

The chief end of my car is the discovery of England. To me it is a land full of stupefying marvels and mysteries; and a day in the car in an English county is a day in some fairy museum where all the exhibits are alive and real and yet none the less delightfully mixed up with books.

Locomotion always fascinated Kipling, and to stories about ships (‘The Ship that Found Itself’) or trains (‘.007’) or airships in the future (‘With the Night Mail’) were now added car stories (‘Steam Tactics’). The ‘discovery of England’ was embodied in Puck of Pook's Hill (1906) and Rewards and Fairies (1910), supplemented by the poems that Kipling contributed to the History of England (1911), written as a school text by the Oxford historian C. R. L. Fletcher. Actions and Reactions (1909), a very miscellaneous col