Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz

Agassiz, Elizabeth Cabot Cary (5 Dec. 1822-27 June 1907), college president, was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Her father, Thomas Graves Cary, was a businessman who became treasurer for the Hamilton and Appleton Mills in Lowell, Massachusetts, and her mother, Mary Ann Perkins, was one of the daughters of Thomas Handasyd Perkins, a wealthy citizen and leading benefactor in Boston. Raised in comfortable circumstances, she was educated at home. In 1850 she married the naturalist Louis Agassiz, who had recently been appointed professor at Harvard. Their marriage was a partnership in which Elizabeth Agassiz managed their complex household, was the devoted mother to three step-children, hostess, and assistant to her husband, who maintained that "without her I could not exist."

To ease the financial burdens of the family, Elizabeth Agassiz suggested opening a day school for girls in their home. Her husband agreed enthusiastically and recruited his Harvard colleagues James Russell Lowell, Conrad Felton, and Benjamin Peirce, among others, to teach their specialties, and himself gave a daily lecture on natural history. Elizabeth Agassiz directed the school (1855-1863), her step-son Alexander Agassiz taught mathematics, and his two sisters taught French and German. This unique day school drew seventy pupils a year from the Boston area and beyond and closed at the outbreak of the Civil War. In 1873-1874 Elizabeth Agassiz was informally involved in the administration of the Anderson School of Natural History, a coeducational summer school founded by Louis Agassiz on Penikese Island. There Louis Agassiz, and later Alexander Agassiz, provided advanced training in science to school and college teachers.

Although she had no formal training and disclaimed any technical expertise in science, Elizabeth Agassiz became a proficient scientific writer. She published two natural histories for children and with Louis Agassiz wrote A Journey in Brazil (1867), an account of the Nathaniel Thayer-funded expedition to the Amazon River based on her daily journals, letters home, and notes she took of Agassiz's shipboard lectures. She was official scribe of the Hassler expedition to South America (1871-1872) and wrote several articles about it for the Atlantic Monthly. After her husband's death in 1873, she compiled Louis Agassiz: His Life and Correspondence (1885), a graceful encomium that muted the harshness of his racist opinions.

Although a conservative on the question of women's rights, Agassiz consistently advocated higher education for women. She joined the Woman's Education Association (1872) and was a member of the committee that launched the Harvard Examinations for Women (1874). In 1879 she was invited to join the organizing committee of an experimental program for "Private Collegiate Instruction for Women" by Harvard professors, created to give women access to Harvard teaching at the undergraduate and graduate levels. The program, nicknamed the "Harvard Annex," flourished and was incorporated as the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women (1882). Agassiz became the first president (1882-1899) and honorary president (1900-1903). She always hoped that Harvard would absorb the Annex as a woman's department and as an inducement helped raise $100,000 for endowment. While she was unable to convince the Harvard Corporation to risk merger, because of its fear of coeducation, her tact and diplomacy helped secure an enduring relationship with Harvard. By an act of 1894 the society was incorporated as a degree-granting institution, coordinate with Harvard, and was renamed Radcliffe College (after Ann Radcliffe, the first woman donor to Harvard in 1643). The Harvard faculty provided all of Radcliffe's faculty, and Harvard's president agreed to cosign the diplomas, signifying equivalence to the Harvard diploma. To strengthen this loose institutional tie further, the Harvard Corporation served as Visitors of Radcliffe. Agassiz successfully quelled discontent among alumnae who disliked this compromise and did not wish to hurry into independence and among others who questioned Harvard's commitment to the education of women.

Agassiz was an effective fundraiser, eliciting funds from the Boston community through "parlor meetings." She purchased Fay House, the college's administrative center, and the surrounding properties that today form the Radcliffe Yard, and she acquired the land for the dormitory quadrangle, which was designed and laid out by her architect nephew, Guy Lowell. The funds for Agassiz House, the student center, were raised largely by her family as an eightieth birthday tribute in 1902.

While not the founder of the college, Agassiz was responsible, as much as any other single individual, for establishing a Harvard education for women and for putting Radcliffe on a permanent footing. At the time of her death, Charles Eliot Norton remembered her as "not a woman of genius or of specially brilliant intellectual gifts," but of judgment, character, and common sense. Said Harvard's president Charles William Eliot, "there never was in this community a more influential woman."

Bibliography

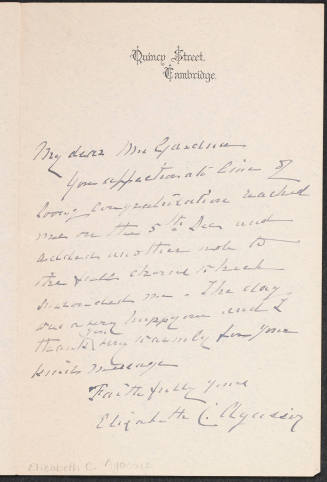

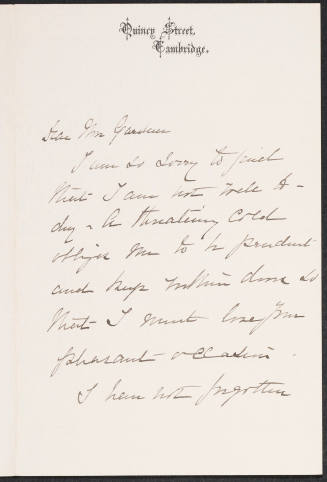

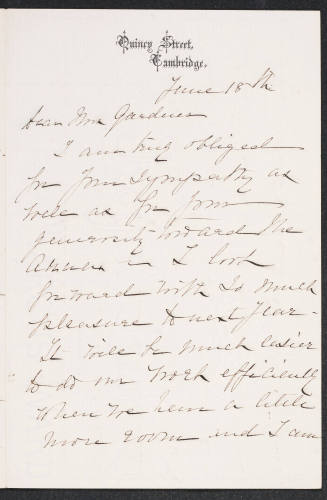

Elizabeth Agassiz's personal papers, including diaries, letters from the Thayer and Hassler expeditions, and other correspondence, are in the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College. Her president's papers are in the Radcliffe College Archives. Other correspondence is in the Elizabeth Briggs Papers and other alumnae collections in the Radcliffe College Archives and in the Louis Agassiz Collection in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. Her works in print, in addition to those mentioned in the text, include A First Lesson in Natural History (1859), Seaside Studies in Natural History (1865) with Alexander Agassiz, and five articles published between 1866 and 1873 in the Atlantic Monthly. Two of the five articles described the voyage on the Amazon River and were incorporated into A Journey In Brazil; three described the Hassler expedition: "The Hassler Glacier in the Straits of Magellan, Atlantic Monthly, Oct. 1872, pp. 472-78; "In the Straits of Magellan," Atlantic Monthly, Jan. 1873, pp. 89-95; and "A Cruise through the Galapagos," Atlantic Monthly, May 1873, pp. 579-84. Her Radcliffe College commencement speeches are in the Harvard Graduates' Magazine (1894-1899). Lucy Allen Paton, The Life of Elizabeth Cary Agassiz: A Biography (1919), contains many extracts from Agassiz's letters and diaries. Louise Hall Tharp, Adventurous Alliance (1959), is still the best biography. Sally Schwager, "Harvard Women: A History of the Founding of Radcliffe College" (Ed.D. thesis, Harvard Univ., 1982), is informative about Agassiz's role in Radcliffe's history and contains an extensive bibliography. Stephen Jay Gould, "This View of Life: Flaws in a Victorian Veil," Natural History 87, no. 6 (June-July 1978), discusses Elizabeth Agassiz's deletions of her husband's racist opinions. The diaries and letters of students who attended the Agassiz School are quoted in Edward Waldo Forbes, "The Agassiz School," Cambridge Historical Society (1954); Mrs. John D. Seaver, Seaview Gazette 11, no. 7 (Feb.-Mar. 1894); and Georgina Schuyler, Radcliffe Bulletin 10 (May 1908).

Jane S. Knowles

Citation:

Jane S. Knowles. "Agassiz, Elizabeth Cabot Cary";

http://www.anb.org/articles/09/09-00007.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Wed Aug 07 2013 17:18:43 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)