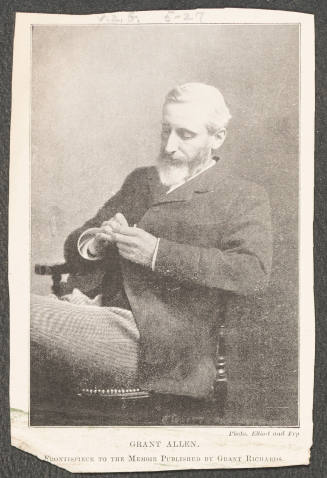

Grant Allen

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n50038383

J. S. Cotton, ‘Allen, (Charles) Grant Blairfindie (1848–1899)’, rev. Rosemary T. Van Arsdel, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, April 2016 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/373, accessed 1 Sept 2017]

llen, (Charles) Grant Blairfindie (1848–1899), writer on science and novelist, was born at Alwington, near Kingston, Ontario, Canada, on 24 February 1848, the second but only surviving son of Joseph Antisell Allen (1814–1900), a clergyman of the Church of Ireland who had emigrated to Canada between 1840 and 1842 and who survived his son by eleven months, dying at Alwington on 6 October 1900. His mother, Charlotte Catherine Ann (1817–1894), was the only daughter of Charles William Grant, fifth Baron de Longueuil.

Grant Allen (as he always styled himself) spent the first thirteen years of his life in the Thousand Islands region, on the upper St Lawrence River, where he developed a love of animals and flowers under the tutelage of his father. About 1861 the family moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where Allen had a tutor from Yale University. A year later the family went to France. Allen studied first at the Collège Impérial at Dieppe and later transferred to King Edward's School at Birmingham. In 1867 he was elected to a postmastership at Merton College, Oxford. His undergraduate career was interrupted by his marriage, at the age of twenty, to Caroline Anne Bootheway (1846–1872), daughter of William Bootheway, a labourer, on 30 September 1868. The marriage was a short one, however, as his wife, who had always been an invalid, soon died. Allen went on to gain a first class in classical moderations and a second class in the final classical school after only a year's reading. In 1871 he graduated BA but proceeded to no further degree. For the next three years he undertook what was to him the uncongenial work of a schoolmaster at Brighton, Cheltenham, and Reading.

On 20 May 1873 Allen married Ellen (1851–1936), the youngest daughter of Thomas Jerrard, a butcher, of Lyme Regis, Dorset, and shortly thereafter he accepted an appointment as professor of mental and moral philosophy at a college at Spanish Town in Jamaica, founded by the government for the education of native peoples. The experiment was a failure, and in 1876 the college was finally closed. Allen returned to England with a small sum of money in compensation for the loss of his post. His three years' experience in Jamaica, however, had an important influence on the development of his mind, having given him time to read and to allow his ideas to clarify. It was during this time that he, always proud of his Scottish blood, acquired a fair knowledge of Old English. He also studied philosophy and physical science and framed an evolutionary system of his own, based mainly on the works of Herbert Spencer. This period marked the end of his formal studies.

While at Oxford, Allen had contributed to a short-lived periodical, the Oxford University Magazine, of which only two numbers appeared (December 1869 and January 1870). When he returned from Jamaica in 1876, he resolved to support himself by his writing. His first book was an essay, Physiological Aesthetics (1877), which he dedicated to Spencer and published at his own risk. It did not sell, but it won for him some reputation and introduced his name to the editors of magazines and newspapers. At this time he began to publish popular scientific articles, some with an evolutionary moral, in The Cornhill, the St James's Gazette, and elsewhere. He also assisted Sir William Wilson Hunter in the compilation of the twelve-volume Imperial Gazetteer of India, in which he wrote the greater part of the articles on the North-Western Provinces, the Punjab, and Sind. For a short time he was on the staff of the Daily News and was also one of the regular contributors to London (1878–9), a short-lived periodical. During this early period (1879–83) his publications were scientific, such as his essay The Colour Sense (1879), which won high approval from Alfred Russel Wallace; three collections of popular scientific articles (Vignettes from Nature, 1881; The Evolutionist at Large, 1881; and Colin Clout's Calendar, 1882), the value and accuracy of which are attested by letters from Charles Darwin and T. H. Huxley; two series of botanical studies on flowers (The Colours of Flowers, 1882, and Flowers and their Pedigrees, 1883); and a short monograph, Anglo-Saxon Britain (1881).

From July 1878 Allen began to contribute short stories first to Belgravia and later to Longman's Magazine and The Cornhill under the pseudonym of J. Arbuthnot Wilson; these were later collected under the title of Strange Stories (1884). His first novel, Philistia, originally appeared as a serial in the Gentleman's Magazine and then was published in the standard three-volume edition in 1884, again under a pseudonym, Cecil Power. The book, a satire on socialism and modern journalism, was largely autobiographical. Although it was not a success with the public, he was encouraged to continue writing, and during the next fifteen years he brought out more than thirty works of fiction, which were both popular and profitable. In addition to healthy sales, in 1891 he won a prize of £1000 from Tit-Bits magazine for his novel What's Bred in the Bone. He had a knack for devising ingenious plots based on contemporary issues and on his wide experience. In All Shades (1886), set in Trinidad, deals with multicultural love; The Tents of Shem (1891) is set in Algeria; The Type-Writer Girl (1897), written under the pseudonym of Olive Pratt Rayner, seized upon the very topical subject of a university-educated woman struggling with the reality of earning her own living; The British Barbarians (1895) is a satire on British society seen from the vantage point of the twenty-fifth century.

Perhaps Allen's most notable and lasting achievement was the novel The Woman who Did (1895), the story of Herminia Barton, a Girton College girl who falls deeply in love with Alan Merrick but decides not to marry him on the grounds of female emancipation. They cohabit and she gives birth to a daughter, but after Merrick's sudden death tragedy overwhelms her life with remorseless precision. Allen honestly intended the novel as a polemic on the position of women and dedicated it to his wife, with whom he passed ‘my twenty happiest years’. It caused a great sensation, and the public read it eagerly, but they were shocked and also puzzled by its lack of humour. Allen's novel prompted two responses (Victoria Cross's The Woman who Didn't and Lucas Cleeve's The Woman who Wouldn't, both 1895), and the notoriety of The Woman who Did helped establish the ‘new woman’ novel as a genre. The novel also claimed the notice of many late twentieth-century feminists for its outspoken analysis of the female dilemma.

Allen's intellectual activity was not confined to novel-writing. He made regular contributions to newspapers, magazines, and reviews, some of which were collected and reprinted in Falling in Love, with other Essays on More Exact Branches of Science (1889) and Postprandial Philosophy (1894). He returned twice to the more abstruse science of his earlier days. In 1888 he brought out Force and Energy, which embodies the results of his lonely reading and cogitations in Jamaica (the first draft had been privately printed in 1876). Contemporary physicists generally declined to discuss his novel theory of dynamics, considering it that of an amateur. Allen nevertheless persisted in it, and in 1894 he presented a copy to a friend with the inscription: ‘It contains my main contribution to human thought. And I desire here to state that, when you and I have passed away, I believe its doctrine will gradually be arrived at by other thinkers’. His other serious work was The Evolution of the Idea of God (1897), an enquiry into the origin of religions. The book is crowded with anthropological lore and contains numerous brilliant aperçus, but it labours under the defect of attempting to explain everything by means of a single theory. In 1894 he issued The Lower Slopes, an unremarkable volume of poems written in his youth. More successful were the detective stories, written later in his life, many of which appeared in the Strand Magazine, and volumes of detective fiction, of which the most notable is An African Millionaire: Episodes in the Life of the Illustrious Colonel Clay (1897). Allen at this time also found a fresh interest in art. He had always been attracted to art as a handicraft, but the appreciation of painting and architecture came later, as the result of repeated visits to Italy. To his scientific mind they fell into their place as branches of human evolution. It is this unifying conception of art, as well as of history, that inspired the series of guidebooks on Paris, Florence, Venice, and the cities of Belgium (1897, 1898) which he wrote in his last years. Throughout all his mature work his interest in science and evolution informs his fiction:

As a scientist Allen was an evolutionist, and as a novelist one of his most persistent themes was the effect of heredity. Even his lighter and more popular works evidence not only his scientific outlook but also his persistent questioning of established convention and of institutions and officials that uphold it. (Christou, 11)

Allen never enjoyed robust health, and London was always distasteful to him. In 1881 he settled at Dorking in Surrey, where he delighted in botanical walks in the woods and on sandy heaths. However, nearly every year he was compelled to winter in southern Europe, usually at Antibes, though once or twice he went as far as Algiers and Egypt. In 1892 he bought a plot of land almost on the summit of Hindhead, Haslemere, Surrey, and built himself a villa which he called The Croft. Here he found that he could endure the severity of an English winter amid surroundings wilder than at Dorking, and with the society of a few congenial friends. He still made trips to the continent, chiefly to prepare his guidebooks. His favourite British holiday resort was on the River Thames, near Marlow. On 25 October 1899 he died of liver cancer at his home at Hindhead. His body was cremated at Woking, Surrey, the only ceremony being a memorial address by Frederic Harrison. He was survived by his second wife, and his only child, Jerrard Grant Allen.

J. S. Cotton, rev. Rosemary T. Van Arsdel