Archibald Cary Coolidge

found: Harvard University Library, July 08, 2015 Papers of Archibald Cary Coolidge : an inventory (Coolidge, Archibald Cary, 1866-1928; born and died in Boston, Massachusetts; Professor of History (1908-1928) at Harvard College and the first Director of the Harvard University Library (1910-1928). He was a scholar in international affairs, a planner of the Widener Library, a member of the American diplomatic service, and editor-in-chief of the policy journal, Foreign Affairs) {http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~hua09004}

found: Wikipedia, July 08, 2015 (Archibald Cary Coolidge; born March 6, 1866 in Boston; died January 14, 1928)[1] was an American educator. He was a Professor of History at Harvard College from 1908 and the first Director of the Harvard University Library from 1910 until his death. Coolidge was also a scholar in international affairs, a planner of the Widener Library, a member of the United States Foreign Service, and editor-in-chief of the policy journal, Foreign Affairs.) {https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archibald_Cary_Coolidge}

Coolidge, Archibald Cary (6 Mar. 1866-14 Jan. 1928), historian, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Joseph Randolph Coolidge and Julia Gardner, prominent Bostonians. His father was the great-grandson of Thomas Jefferson; his mother was the daughter of a banking and shipping magnate. Despite their wealth and social position, the Coolidge family was Spartan, staunchly Unitarian, and aloof from much of Boston society.

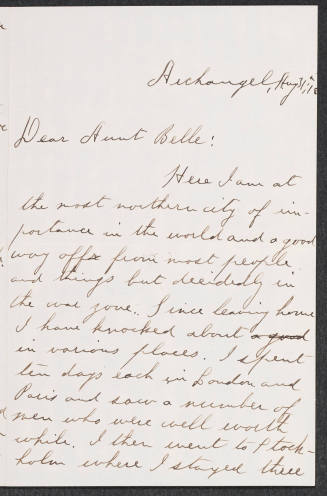

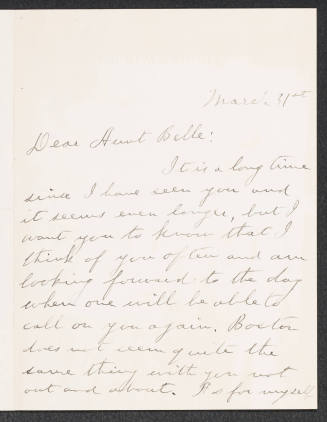

Coolidge attended Harvard College, graduating summa cum laude in history in 1887 and leaving shortly thereafter to study for a Ph.D. in history at the University of Freiburg, Germany. In Europe Coolidge traveled widely and attempted to broaden his experience beyond the confines of his university. He studied for a number of terms at both the University of Berlin and the École des Sciences Politiques in Paris and mastered a number of European languages, as well as Russian. In the winter of 1890-1891 he worked for six months as acting secretary of the legation in St. Petersburg, and afterward he traveled throughout Russia. The following spring he served as a private secretary to his uncle Thomas Jefferson Coolidge, the American minister to France. By the time Coolidge received his doctorate in 1892, he had grown firm in his belief that a complete education required extensive travel and varied experience. Unlike many of his American contemporaries he continued throughout his life to expose himself to new languages and cultures.

After serving briefly as secretary of the American legation in Vienna, Coolidge returned to Boston and to Harvard, becoming an instructor in history in 1893. Coolidge lavished his attentions on Harvard single-mindedly, undistracted by a family of his own. He proposed and taught Harvard's first course in Russian history and pushed the university to teach Russian and other Slavic languages and literature. He broadened the horizons of the historical discipline in the United States by advancing the study not only of Russia and Northern and Eastern Europe but of other regions long ignored by American historians, including Latin America.

Coolidge sought above all to analyze the past as dispassionately as possible. Unlike many of his peers he maintained a neutral view of Russian expansion and stressed this to his students. Coolidge's desire for historical objectivity steered him away from theory. His most famous book, The United States as a World Power (1908), went through ten editions as well as printings in French, German, and Japanese. Yet like his other two books, Origins of the Triple Alliance (1917) and Ten Years of War and Peace (1927), it was distinguished by its judicious tone rather than by any interpretative breakthroughs. The first two books grew out of a series of public lectures and the third out of a collection of magazine articles. Compared to many of his contemporaries, Coolidge produced few major works of archivally based historical scholarship.

From his elevation to professor in 1908 until his death in Boston, Coolidge continued his efforts to improve Harvard. After President Abbott Lawrence Lowell named him director of the university library in 1910, he overhauled the catalog and classification systems and increased the number and quality of the library's acquisitions. Urging Harvard to "buy first and find the money afterwards" (Byrnes, p. 120) and acting on this dictum, Coolidge personally purchased most of the 30,000 volumes in the university's Slavic collection and paid for their cataloging himself. He was critical in advancing the plans for Widener Library, the centerpiece of the university's famous library system.

Coolidge's lifelong work for Harvard did not prevent him from briefly serving the U.S. government as well. Coolidge was one of the first academics to join "The Inquiry," a research group convened by Colonel Edward M. House in 1917 to prepare the United States for the upcoming peace conference. Coolidge directed the Eastern European division, based in Widener Library, which gathered information about Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Russia's western frontier. In May 1918 he left the group to study conditions in Russia for the Department of State; the following year he spent five months in Vienna reporting on the situation in Central and Eastern Europe for the benefit of American postwar planners. He next joined the American Commission to Negotiate Peace in Paris to help draft the Austrian and Hungarian peace treaties and to assess the Austrian response to Allied proposals. He finished his work for the U.S. government after the war, when at Herbert Hoover's request he headed a liaison division of the American Relief Administration in Russia.

When Coolidge left Russia for Boston in March 1922, he was invited to become the first editor in chief of Foreign Affairs, the journal of the newly founded Council on Foreign Relations. Despite his desire to return to teaching and directing the library, Coolidge viewed his six years with the prominent quarterly as important for exposing the informed public to discussions of U.S. foreign policy and international affairs. As editor he outlined the policy that Foreign Affairs maintained throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, insisting that the journal "not devote itself to the support of any one cause, however worthy." He consciously sought articles from those he disagreed with, including the isolationist Senator William E. Borah.

Aside from his three books, Coolidge edited three others, wrote sixteen scholarly articles and numerous reviews, and contributed frequently to the Nation, the New York Evening Post, and Foreign Affairs. But Coolidge was not anxious for political influence; he believed strongly that a scholar should provide accurate information without becoming politically involved. Although he helped found one of the most famous journals in international affairs, he was circumspect about advancing his opinion if he thought it might influence political decisions. Reluctant to embroil himself in the debate over U.S. entry into World War I, for example, he avoided publicly announcing his opinion on the war's origins until after the United States had abandoned neutrality. Similarly, despite his formidable expertise on the problems of Central and Eastern Europe, it is unlikely that he significantly influenced the peace process. Coolidge usually preferred to make his contributions unobtrusively, as when he quietly trained students for scholarly or diplomatic careers. This political reticence, like his lack of interest in theory, has perhaps diminished his work in the eyes of recent historians. But by the standards of his day, Coolidge was eminent.

Bibliography

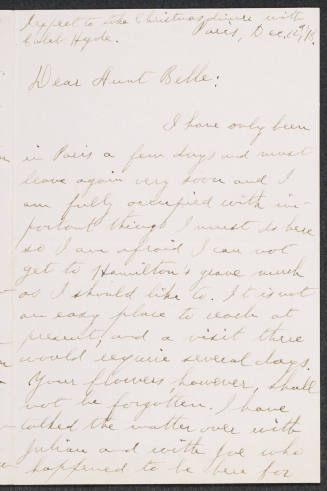

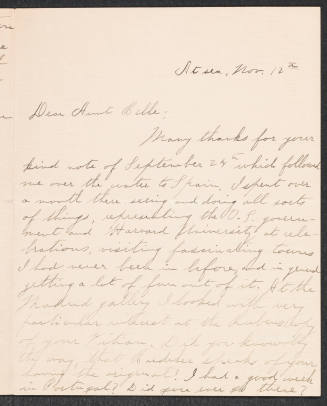

Coolidge's personal papers, which include his extensive correspondence and several unpublished manuscripts, are in the Harvard University Archives. The most recent biography is Robert F. Byrnes, Awakening American Education to the World: The Role of Archibald Cary Coolidge, 1866-1928 (1982). Byrnes's invaluable bibliographical essay and bibliography provide an excellent guide for further work on Coolidge. See also Robert A. McCaughey, International Studies and Academic Enterprise: A chapter in the Enclosure of American Learning (1984), pp. 74-82. An obituary is in the New York Times, 15 Jan. 1928.

Emily B. Hill

Citation:

Emily B. Hill. "Coolidge, Archibald Cary";

http://www.anb.org/articles/14/14-00118.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:06:38 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.