Charles Townsend Copeland

found: NUCMC data from Library of Congress Manuscript Division for His Collection, 1898-1925 (Copeland, Charles Townsend, 1860-1952; educator, editor, and author)

Charles Townsend Copeland, (born April 27, 1860, Calais, Maine, U.S.—died July 24, 1952, Waverly, Mass.), American journalist and teacher, who was preeminent as a mentor of writers and as a public reciter of poetry.

Copeland was educated at Harvard University (A.B., 1882), and, after a year as a teacher at a boys’ school in New Jersey and another at Harvard Law School, he was a drama critic and book reviewer for the Boston Advertiser and the Boston Post for nine years. In 1893 he returned to Harvard as an instructor in the English department, becoming assistant professor (1917) and Boylston professor (1925) until his retirement in 1928.

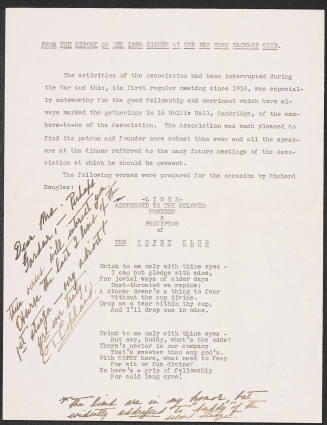

In his writing course at Harvard from 1905 Copeland had as students such later famous writers as poets T.S. Eliot and Conrad Aiken; historians Van Wyck Brooks and Bernard De Voto; journalists Heywood Broun, John Reed, and Walter Lippmann; playwrights S.N. Behrman and Robert Sherwood; novelists Oliver La Farge and John Dos Passos; critics Gilbert Seldes, Brooks Atkinson, and Malcolm Cowley; and editor Maxwell Perkins, who later edited Copeland. So great was Copeland’s popularity that his students founded an alumni association for him in 1907, which persisted until 1937. His Monday evening socials for students, with unannounced guests such as John Barrymore, Robert Frost, Ernest Hemingway, and Archibald MacLeish, became legendary. From 1906 to 1926 he lectured at Lowell Institute, Boston, in university extension courses on English literature.

His The Copeland Reader (1926), an anthology of selections from his favourite works, indicated the scope of his interests and was extremely popular. Encyclopedia Briannica, accessed 10/11/2017

Copeland, Charles Townsend (27 Apr. 1860-24 July 1952), educator, was born in Calais, Maine, the son of Henry Clay Copeland, a lumber dealer, and Sarah Lowell. A small, shy lad, he attended Calais High School, where he edited and wrote for the school paper. He matriculated at Harvard College in 1878, was an editor of the Harvard Advocate, and graduated in 1882 with an A.B. He taught in a private boys' school in Englewood, New Jersey (1882-1883), attended Harvard Law School unhappily (1883-1884), and after a long vacation in Calais worked for a few months in 1885 as a book reviewer for the Boston Advertiser. Transferring to the Boston Post, he reviewed books and plays for it until 1892. He was usually respectful in discussing books by established authors, but he was also among the first critics to explain the greatness of Rudyard Kipling, Leo Tolstoy, and Ivan Turgenev to Americans. Although Copeland read assiduously, he had ample time to attend plays in Boston, in the course of which he saw stars such as Lawrence Barrett, Sarah Bernhardt, Dion Boucicault, Edwin Booth, Benoit Constant Coquelin, Joseph Jefferson, Fanny Kemble, Lily Langtry, Julia Marlowe, Helena Modjeska, Ada Rehan, and Tommaso Salvini.

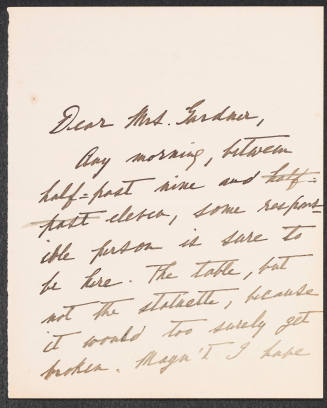

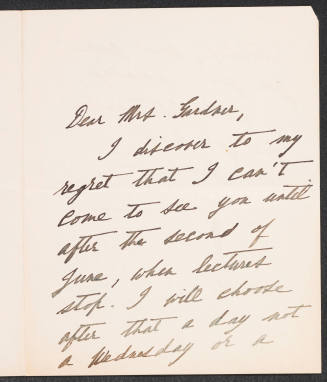

In 1893 Copeland returned permanently to Harvard. At first he was an instructor in English A, a required freshman composition course. An eloquent public speaker and reader, he had a deep and resonant voice (early in adulthood he considered becoming an actor but gave up the idea because of his diminutive size). He partly satisfied his desire to be histrionic by giving voluntary lectures on some of his favorite authors to immensely pleased groups until 1896. Both before and after this, he regularly invited swarms of undergraduates to his dormitory rooms, where they listened to his delightful conversation and were encouraged to share their literary insights. Copeland edited Letters of Thomas Carlyle to His Youngest Sister (1899), wrote Life of Edwin Booth (1901), and coauthored, with Henry Milner Rideout, a friend from Calais and his former pupil, Freshman English and Theme Correcting in Harvard College (1901). Copeland's handling of Carlyle's letters was professionally acceptable and included a sound introduction. His biography of Booth, published as part of Mark Antony DeWolfe Howe's brief Beacon Biographies, was based on previously published sources but was rendered valuable by Copeland's informed love of the theater. The book on composition was initially a useful text for Copeland's freshman course, given its requirement of daily written essays; but its fame soon spread to campuses nationwide. His own English 12 was also a writing course, in which students prepared weekly 1,000-word compositions and read them to Copeland. Enrollment was limited to thirty students.

Copeland also taught lecture courses on Dr. Samuel Johnson and his contemporaries, Sir Walter Scott, English letter writers, and English Romantic poets. His classes became so popular that as many as 250 students often enrolled in a given course. In the 1905-1906 academic year Copeland felt that his popularity might be due to his lenient grading; so he surprisingly flunked more than half of one class. Since several seniors would immediately be ineligible to graduate, the administration persuaded him to relent.

Copeland's promotion to assistant professor was delayed until 1910 because Harvard president Charles William Eliot called him "unproductive." In 1917 he was promoted to associate professor. In 1925, when he was sixty-five years of age, he was appointed to the coveted position of Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory. He retired three years later, by which time he was acknowledged as a major professional influence on many students who had gone on or would go on to achieve greater recognition than "Copey" himself, as they dubbed their favorite teacher. His students in English 12 alone included J. Donald Adams, Conrad Aiken, Robert Benchley, Earl Derr Biggers, Van Wyck Brooks, Heywood Broun, Malcolm Cowley, Bernard DeVoto, John Dos Passos, T. S. Eliot, Norman Foerster, Granville Hicks, Oliver La Farge, Walter Lippmann, Haniel Long, Maxwell Evarts Perkins, John Reed, Kermit Roosevelt, Gilbert Seldes, and Robert Sherwood. The most eminent of Copeland's nearby Radcliffe College students, who took writing courses he conducted there for decades, were Rachel Lyman Field, Katharine Fullerton Gerould, and Helen Keller.

Most of his students idolized Copeland. In The Story of My Life (1902), Keller waxed ecstatic in describing her response to Copeland's presentation of the Old Testament. On the dedication page of his Insurgent Mexico (1914), John Reed named Copeland and wrote: "I never would have seen what I did see had it not been for your teaching me." Maxwell Perkins became his publisher. Some students, however, found both his method and his substance unappealing. They bridled at his emphasis on the beginning and the ending of composition elements, his hatred of long sentences--which he called "swag-bellied"--and his demand for journalistic vividness. Brooks, Dos Passos, and Eliot, for example, went on record as feeling that they had not profited from his classes, while Aiken was put off by what he regarded as Copeland's vanity and demand for adulation.

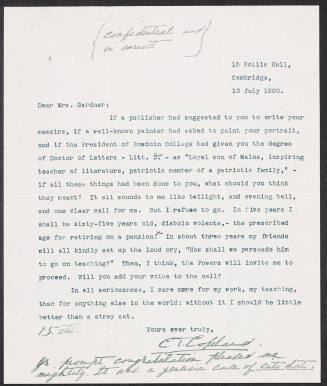

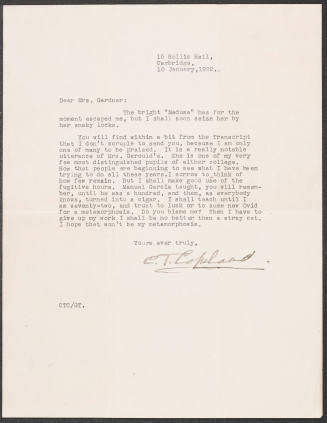

Copeland never became an outstanding biographer or critic. He devoted his limited physical energy to his teaching and informal, conversational tutoring. He always wrote by hand, slowly and with difficulty, and he was a habitual procrastinator. He spent a great deal of time enjoying food; he once rewrote Alexander Pope's "To err is human, to forgive divine" as "To eat is human, to digest divine," and he was too fond of alcohol, although he said he was a "drinkard" not a "drunkard." Being a lifelong bachelor, he lacked what might well have been a beneficial feminine influence for his professional betterment. In July 1920 he wrote Perkins that he preferred his teaching over anything else in life, that without such work he would be like "a stray cat." For years Perkins hoped that Copeland would write his memoirs, which, however, were forever postponed. Perkins did succeed in encouraging him to assemble, with Thurman Losson Hood, The Copeland Reader: An Anthology of English Poetry and Prose (1927), a financially successful 1,687-page book of passages lending themselves to oral presentation; and The Copeland Translations: Mainly in Prose from French, German, Italian and Russian (1934). Dedicated to Perkins, this 1,080-page book was a financial failure. Copeland planned to follow it with a Greek anthology but delayed and abandoned the idea in 1937, pleading insomnia and tinnitus to Perkins.

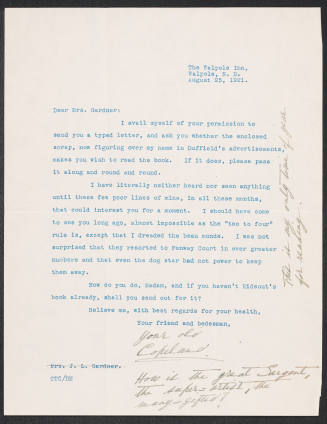

In 1928 Copeland went abroad for the first and only time, making pilgrimages to various English and Scottish literary shrines. In 1930 more than 300 friends met at the Harvard Club of New York City to honor him. Beginning in 1931, at the suggestion of Harvard's dean of freshmen, Copeland welcomed to his dormitory quarters, and after 1932 to his Cambridge apartment, two or three especially recommended freshmen for a lively talk each week during the school year; only when well into his eighties did he abandon this pleasure. Until 1937 he rejoiced in attending annual meetings, held every spring in New York, of the Charles Townsend Copeland Association, which had been founded by devoted friends in 1906. His last years were marked by a diminution of mental acuity, and he died in a hospital in Waverly, Massachusetts. Granville Hicks summed up Copeland's contradictory nature by commenting on "his absurd dignity, his amusing poses, his pretended ferocity, and his ironic courtesy." The conclusion of J. Donald Adams that Copeland "left his imprint upon more lives in their budding period than any other American teacher of his time" is more deservedly admiring.

Bibliography

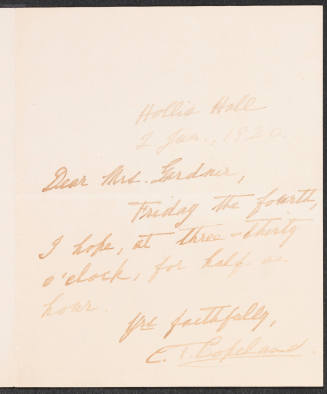

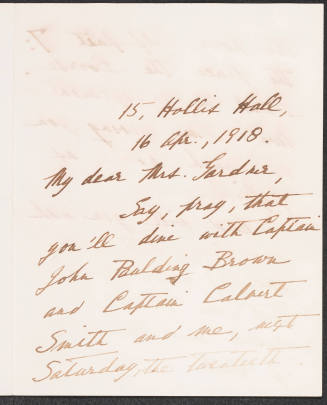

Copeland's papers are in the archives of Harvard University and in its Houghton Library. Additional correspondence is in the Robert Silliman Hillyer Papers, Syracuse University Library, and the William Stanley Beaumont Papers, University of Virginia Library. J. Donald Adams, Copey of Harvard: A Biography of Charles Townsend Copeland (1960), is the most informative biography. Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, "Charles Townsend Copeland," in her Fire under the Andes: A Group of North American Portraits (1927), pp. 125-41; Rollo Walter Brown, " 'Copey,' " in his Harvard Yard in the Golden Age (1948), pp. 121-37; and David McCord, "Copey at Walpole," in his In Sight of Sever: Essays from Harvard (1963), pp. 3-7, all describe Copeland's ability to share his passion for literature with others. "Copey," Time, 17 Jan. 1927, discusses the respect accorded to Copeland by students and friends. Granville Hicks, John Reed: The Making of a Revolutionary (1937), and Robert A. Rosenstone, Romantic Revolutionary: A Biography of John Reed (1975), reveal Reed's admiration for Copeland. Kermit Vanderbilt, American Literature and the Academy: The Roots, Growth, and Maturity of a Profession (1986), denigrates Copeland for his meager classroom treatment of American writers. An obituary is in the New York Times, 25 July 1952.

Robert L. Gale

Citation:

Robert L. Gale. "Copeland, Charles Townsend";

http://www.anb.org/articles/09/09-00201.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:08:34 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.