Walter Crane

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n79060706

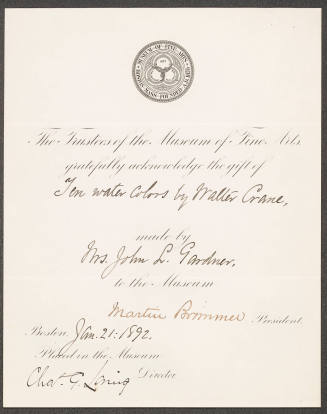

Crane, Walter (1845–1915), illustrator, designer, and painter, was born on 15 August 1845 at 12 Maryland Street, Liverpool, the third child of Thomas Crane (1808–1859), a portrait painter well established in the north-west of England, and his wife, Marie Kearsley. When he was three months old the family moved to Torquay because his father was thought to be consumptive, and Walter Crane spent a happy childhood there. His earliest memories included the ships in the harbour and the times the circus came to town. He was good at drawing but school brought on nervous attacks, so he stayed at home, learning from his father's work, stocking his mind from illustrated books, and sketching in the fields. Animals were his favourite subject. Thomas Crane's health improved in Torquay, and in 1857 he moved his family to London, hoping to get more work. Seeing a career in art for his son, he took him to the National Gallery and to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert). In January 1859 Walter Crane was apprenticed to the wood engraver W. J. Linton to learn the art of drawing on wood for illustration. He was thirteen. Six months later his father died.

Crane came thus abruptly out of childhood, walking from his mother's house in Notting Hill to Linton's workshop off the Strand each morning and back again in the evening. At the end of his three-year apprenticeship he could help to support his mother, sisters, and younger brother. But he had his own ambitions as well. He had entered a world of publishers, printers, artists, engravers, and journalists where art and commerce sat down together. This was the golden age of Victorian illustration, and he might one day shine alongside D. G. Rossetti and Charles Keene. He was reading Auguste Comte, J. S. Mill, Herbert Spencer, and Shelley and catching heady glimpses of how humanity, free of the old theologies, might take the future into its own hands. And he was painting on his own account, subjects from Keats and Tennyson. In 1862 his Lady of Shalott was hung at the Royal Academy. Though he was still in his teens and looking for work as a freelance illustrator, he seemed to have gone beyond his father.

In 1865 Crane was asked to contribute illustrations to a series of books for very young children, nursery rhymes and fairy tales, to be printed by Edmund Evans, the leading woodblock colour printer in London, and published by Routledge. Over the next ten years Crane illustrated thirty-seven of these Toy Books, as they were known. After the first nine his work began to emulate Japanese prints, with decorative compositions in flat, or very deep, perspective; and he began to furnish his pictures with the fashions and domestic bric-à-brac of the aesthetic movement, then on the rise in London—fans, blue-and-white china, and peacocks' feathers. Nursery rhymes and fairy tales are full of pigs going to market and dishes eloping with spoons. Crane had a taste for such fantasy, especially the anthropomorphic animals—was his name not a bird? His peculiar sensibility wedged animal lunacy up against high fashion. Picture books for children which did not moralize and colour printing from wood both flourished in the mid-Victorian period. Evans's skill and Crane's imagination raised them to new levels, and the Toy Books were an enormous success.

On 6 September 1871 Crane married Mary Frances Andrews (c.1846–1914), the daughter of a country gentleman from Essex, and they spent the next eighteen months in Italy. Crane worked at his book illustrations, painted in the landscape, and made portraits of his demure-looking wife. He was also working, in these years, on allegorical paintings with themes of human life and destiny inspired by the positivism of Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. He painted such allegories almost all his life, giving them such titles as The Bridge of Life and The Roll of Fate, and he valued them above his other work. It was his ambition to show them at the Royal Academy, but he showed there only once after 1862. Instead they appeared each year at the Dudley and the Grosvenor and other London galleries, never to any acclaim. That was hard to bear, and the success of his children's books put salt in the wound. The public acclaimed him as ‘the academician of the nursery’, but he wanted to be known as a distinguished allegorical painter. Much of his life was spent in pursuing this difficult ambition and, at the same time, in creating tolerable substitutes for it.

When the Cranes returned to London in 1873 they moved into a house in Wood Lane, Shepherd's Bush, then still on the edge of the city. Here, and later at Beaumont Lodge nearby, Crane lived and worked for almost twenty years. The couple entertained a lot and moved in the artistic and fashionable circles of Holland Park; George Howard, later twelfth earl of Carlisle, was a friend and patron, and so was Lord Leighton. Crane knew, and looked up to, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. At this time he widened the scope of his œuvre. He began to work as decorative artist, designing wallpapers, tiles, printed textiles, posters, stained glass, embroideries, decorative plasterwork. He was versatile and prolific. At first manufacturers wanted nursery tiles and nursery wallpapers, but he wanted to escape from the nursery. (Besides, he now had rivals there in Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott.) He began to illustrate books for adults and works of literature. And in his decorative work he developed a versatile, linear style with scrollwork and emblematic, vaguely classical figures derived from his allegorical paintings. The aesthetic movement flourished in the 1870s, raising the status of decorative art, taking it seriously. That was what Crane wanted. It seemed as if decorative art might be a third way, between his success as an illustrator and his aspirations as a painter.

In 1884, after some friendly argument with William Morris, Crane became a socialist. He joined the Social Democratic Federation along with Morris, and as Morris changed allegiance Crane followed, joining the Socialist League later in 1884 and the Hammersmith Socialist Society in 1890. This was more a matter of personal loyalty than of shared beliefs, for the sources of Crane's socialism were different from Morris's: the radicalism of his master W. J. Linton, the positivist belief in progress, memories of the Paris commune of 1871. He became the artist of the cause, designing posters, trade-union banners, cartoons, and newspaper headings, adapting the emblematic figures of his paintings to socialist themes. His The Triumph of Labour, drawn for May day 1891 and reproduced in Crane's Cartoons for the Cause, 1886–1896 (1896), is a Renaissance-style triumphal procession rendered in the gritty texture of wood-engraving and filled with sturdy workers, bullock carts, and banners. Morris said it was the best thing he had ever done.

In the 1880s Crane also became active in the politics of art. The arts and crafts movement championed the claims of decorative art in the 1880s, as the aesthetic movement had in the 1870s, but it had more intellectual weight, and it had its own organizations. The Art-Workers' Guild, founded in 1884, brought architects and fine and decorative artists together under the banner of ‘the unity of art’. Crane was a founder member. But the guild was a private club, not an exhibiting body, so Crane and the metalworker W. A. S. Benson led a movement to establish a separate exhibiting body for the decorative arts. The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, founded in 1888, held large and successful exhibitions in London, at first annually and then triennially. Crane was president from 1888 to 1893, William Morris from 1893 until his death in 1896, and Crane again until 1912. The society was a public platform for Crane, and after Morris's death he was probably the best-known decorative artist in Britain. This was the kind of prominence he had wished to enjoy as a successful painter.

In 1892 the Crane family moved from Shepherd's Bush to 13 Holland Street, off Kensington Church Street. They now had three children, Beatrice (b. 1873), Lionel (b. 1876), and Lancelot (b. 1880); two others did not survive their early years. Mary Crane was no longer the demure figure of the Italian portraits but a plump, slightly fantastic woman who drove herself alone round Kensington in a buggy, flouting propriety in a William Morris flower-patterned dress. They lived a life of self-conscious bohemianism. The house was full of pewter and china, carved figures, Indian idols, a live alligator, model ships, a marmoset that slept in the fireplace, Crane's unsold paintings, all higgledy-piggledy and gathering dust. Amid all this Crane played the part of the artist, a small, dapper man with carefully curled moustaches and a little beard, a flowing yellow silk tie, and a velvet coat. Colleagues were apt to laugh at him, and they mostly thought his earliest works, the Toy Books, were the best. But he was a lovable figure, and they indulged his staginess. Both he and Mary Crane loved dressing up and they threw enormous parties. For Lionel's twenty-first birthday they invited seven hundred people. Crane dressed up as a crane and Mary as an enormous sunflower.

In the 1890s and 1900s Crane enjoyed fame and public honours. In 1891–2 a major retrospective exhibition of his work toured the United States. In 1893 he was appointed director of design at Manchester School of Art. From 1893 to 1896 his exhibition toured Europe, and he was delighted to find that German collectors and museums bought his allegorical paintings, which chimed with German symbolist work. In 1898 he was appointed principal of the Royal College of Art. Three separate monographs were published on his work. A new and much larger retrospective opened in 1900 at the Applied Arts Museum in Budapest, where he and Mary Crane were fêted. It then toured Austria and Germany. At this point the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, of which he was still president, was invited to assemble the English contribution to the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art, due to open in Turin in 1902. Lacking financial resources, Crane and others simply moved his exhibition to Turin and added other arts and crafts exhibits. Crane was decorated by Victor Emmanuel III for his part in the exhibition, and from then on called himself Commendatore Crane.

In these decades Crane published an autobiography and a half-dozen books in which, among various technical subjects, he set out his conviction that decorative art had a distinguished history and wide intellectual scope; that it was the art of the people and would flourish only when the people were free; and that the arts and crafts movement was its modern champion against the threat of commercialism and the machine. These were typical arts and crafts arguments and were learned mostly from Morris, though they lacked Morris's passionate medievalism and mature socialism. Some of these books were translated into Dutch, German, and Hungarian. The boy who found school difficult, the young man who illustrated children's books, was now an authority, a writer on art.

Crane loved appearing on the public stage, but there were flaws in his performance. At Manchester he failed to steer the school towards a more practical, arts and crafts kind of teaching as was hoped, and he resigned after three years. At the Royal College he resigned after only one year. At Turin the English contribution was criticized in the press as old-fashioned, ill-displayed, and dominated by one man. The truth is that Crane was not a good chairman and that he hung on to the presidency of the Exhibition Society too long. Around 1910 the society was in trouble, losing money on exhibitions and shaken by the discontent of younger members. The arts and crafts architect C. R. Ashbee, who was younger than Crane but had been with the society since the beginning, wrote after Crane's death:

He failed us in the crisis ... He could not give the younger men the lead they needed. That failure of his has I think destroyed the Society as a vital force ... Perhaps he was too gentle, too much a creature in a fairy story. (Ashbee, 266)

Ashbee was right. Crane's talent lay far from the public world, and by this time far in his past, with little children and domesticity. His best things were his lightest things. In the Beinecke Library at Yale University, and in the Houghton Library at Harvard University, are twenty-nine shiny black notebooks, in addition to which there are three notebooks in the Senate House Library, University of London. These are some of the stories he made up for his own children at bedtime, telling them in pictures. They were known in the family as the black books. There is not much in his work that is finer than the visual wit and tenderness of these books, which were the work, Crane tells us, of the odd half-hours of winter evenings.

On 18 December 1914 Mary Crane was found dead on the railway line near Kingsnorth in Kent. The coroner's jury returned a verdict of suicide during temporary insanity. Walter Crane did not long outlive his wife: he died at Horsham Cottage Hospital, in Sussex, on 14 March 1915.

Alan Crawford

Sources

W. Crane, An artist's reminiscences (1907) · I. Spencer, Walter Crane (1975) · G. Smith and S. Hyde, eds., Walter Crane, 1845–1915: artist, designer and socialist (1989) · W. Crane, The work of Walter Crane, with notes by the artist (1898) · P. G. Konody, The art of Walter Crane (1902) · A. Crane, ‘My grandfather, Walter Crane’, Yale University Library Gazette, 31/3 (1957), 97–109 · C. R. Ashbee, ‘The Ashbee memoirs’, 7 vols., 1938–40, V&A NAL, 7.265–8 · P. Stansky, Redesigning the world: William Morris, the 1880s, and the arts and crafts (1985) · C. Dakers, The Holland Park circle (1999) · The Times (21 Dec 1914), 5 · W. Rothenstein, Men and memories: recollections of William Rothenstein, 2 vols. (1931–2) · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1915) · m. cert.

Archives

Kensington Central Library, London, watercolours, drawings, designs, proofs, wallpapers, and corresp. · priv. coll., watercolours, drawings, designs, sketchbooks, family portraits, and corresp. · V&A, corresp. · Yale U., Beinecke L., letters and literary MSS :: BL, corresp. with Macmillans, Add. MS 55232 · BL, corresp. with May Morris, William Morris, G. B. Shaw, and others, Add. MS 50531 · BLPES, corresp. with Fabian Society and independent labour party · Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, Howard papers, corresp. with George Howard, earl of Carlisle · Harvard U., Caroline Miller Parker collection, drawings, designs, sketchbooks, MSS, proofs, and corresp. · Harvard U., Houghton L., letters to James Stanley Little · JRL, letters to M. H. Spielmann · Ransom HRC, corresp. with John Lane · Richmond Local Studies Library, London, corresp. with Douglas Sladen · U. Glas. L., letters to D. S. MacColl · UCL, letters to Sir Francis Galton · V&A, Forster Library, papers of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society · Yale U., Catherine Tinker Patterson collection, drawings, designs, MSS, proofs, and corresp.

Likenesses

Elliott & Fry, photograph, c.1875, NPG · G. Simonds, bronze bust, 1889, Art Workers Guild, London · G. F. Watts, oils, 1891, NPG [see illus.] · T. A. Gotch, photograph, 1906, RIBA · photograph, c.1910, NPG · W. Crane, self-portrait, oils, 1912, Uffizi Gallery, Florence · Barraud, photograph, NPG; repro. in Men and women of the day, 4 (1891) · W. Crane, self-portrait, print (aged sixty), BM · W. Rothenstein, lithograph, BM, NPG

Wealth at death

£3119 8s. 3d.: administration, 18 May 1915, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Alan Crawford, ‘Crane, Walter (1845–1915)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2013 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/32616, accessed 12 Oct 2017]

Walter Crane (1845–1915): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32616