John Drinkwater

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n50029152

Drinkwater, John (1882–1937), poet and playwright, was born at Leytonstone, Essex, on 1 June 1882, son of Albert Edwin Drinkwater (1852–1923), schoolmaster and, later, actor, and his wife, Annie Beck, née Brown (d. 1891). He was educated at Oxford high school from 1891 to 1897, leaving before his sixteenth birthday. Like his contemporary Harley Granville Barker, in later life he frequently expressed regret and embarrassment at not having had a university education. He had some leanings towards a theatre career but his father, who himself had deserted schoolteaching to become an actor in 1896, nevertheless steered his son in the direction of commerce, securing for him an appointment in the Nottingham offices of the Northern Assurance Company. The young Drinkwater did fairly well in his new profession, though he hated it throughout the twelve years of it that he had to endure. It provided (though only just) a livelihood and gave him independence of a sort, but he was desperately poor. He wrote in his autobiography that the very first book that he was able to buy for himself was The Ingoldsby Legends, and he had to wait until he was twenty before he dared lash out so extravagantly. He effected his escape eventually, partly by discovering his own writing talent and partly by way of an invitation from Barry Jackson, who was setting up a new and exciting provincial theatre in Birmingham. Jackson's invitation, founded upon some modest amateur acting experience that Drinkwater had had in Nottingham, was to play Feste in an amateur production of Twelfth Night in the extensive garden of The Grange, the palatial mansion belonging to Barry Jackson's father. Jackson was two years senior to John Drinkwater. Both were passionate about the theatre, and liked each other. In 1907 they joined forces to found a group of amateur actors which they called the Pilgrim Players. Eschewing light, popular fare, the Pilgrim Players gradually gained a serious-minded Birmingham audience for plays of quality. Among the players was Drinkwater's wife, Kathleen Walpole (Cathleen Orford; b. 1881/2) , whom he had married on 11 January 1906. After five years, with Jackson's money behind them, they turned their amateur theatre company into a professional one and erected a theatre building of their own, calling it the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. It opened in 1913 with a production of Twelfth Night, with Drinkwater as Malvolio and Cathleen Orford as Maria. Drinkwater had also written a prologue-like celebratory verse, ‘Lines for the Opening of the Birmingham Repertory Theatre’, to be spoken by Barry Jackson. It is among Drinkwater's Poems, 1908–1914 (1917). He became the new theatre's general manager—a position that included acting, directing, and play-writing as well as the more ordinary managerial duties. By 1918, when he left Birmingham in triumph to take his own play, Abraham Lincoln, to London and thence to New York, he had played about forty parts at the new Repertory Theatre and directed sixty productions in six years.

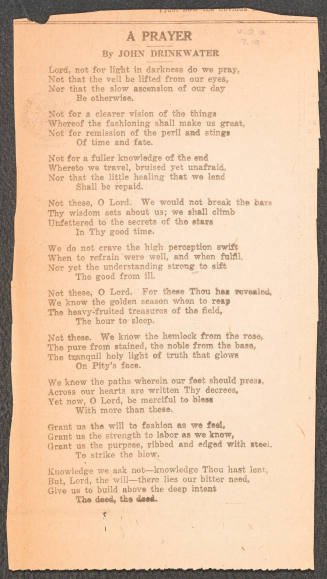

Also during his Birmingham years Drinkwater had established himself as a published poet whose lyric verses had begun to win a good deal of respect and to find their way into the better anthologies. In the second volume of his unfinished autobiography (Discovery, 1932) he tells about the moment, walking home late one night along the Moseley Road in January 1903, when he realized that poetry was his true vocation. His first small book of verse was The Death of Leander and other Poems (1906), and in the next twelve years he published three more, and contributed individual poems to eight or nine leading national magazines and anthologies, including Edward Marsh's Georgian Poetry (1912; see Georgian poets) and New Numbers (1914), published by the Dymock poets. These poems included the beautiful and much-anthologized ‘Moonlit Apples’, which appeared in his collection called Tides in 1917.

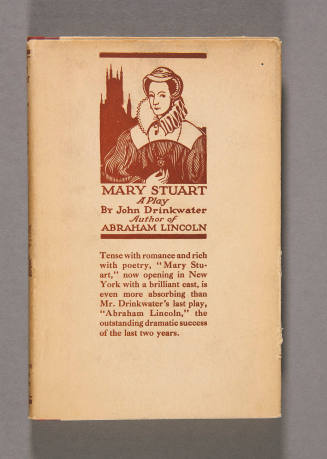

Drinkwater returned from America in 1920 a temporarily famous man, much respected for his plays and his poetry. But his writing, in the later 1920s and early 1930s—except in the case of Bird in Hand in 1927—failed to live up to the promise of his first, fine, careless rapture and his fame gradually declined. Bird in Hand was produced at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 1927, with Laurence Olivier and Peggy Ashcroft in the leading parts, under Drinkwater's direction. After an absence of many years he also returned to acting, though not at Birmingham. He played Prospero at the Regent's Park Open Air Theatre in 1933 and Duke Senior, also at Regent's Park, in 1934. Also in 1934 he played Malvolio at His Majesty's Theatre. All in all, it must in honesty be said that his reputation died before he did.

Drinkwater's marriage to Cathleen Orford was dissolved in 1920, and on 16 December 1924 he married, at the Kensington register office, the violinist Daisy Fowler (b. 1892/3); she was the daughter of Joseph Arthur Kennedy, schoolmaster, of Norwood, Adelaide, Australia, and formerly wife of Benno Moiseiwitsch, the Russian pianist. Their daughter, Penelope, was born in 1929. She is saluted in a group of six poems in Summer Harvest: Poems, 1924–33 (1933). Qua poetry they are mawkishly embarrassing; but as snatches of overheard private conversation or glances at the kind of private diaries that ought never to be published, they are interesting, informative, and moving.

There are signs in one of his books that Drinkwater, for all his passion and fervour, may have inadvertently missed his true calling. The book is The Gentle Art of Theatre-Going, commissioned for a Gentle Art of ... series and published in 1927. The circumstances of its publication strongly suggest that it was mere bread-and-butter work, but the text itself rises above this level. Its liveliness and persuasiveness suggest that he would have made a first-class theatre critic if he had given himself to that occupation on a regular and long-term basis.

Through the 1920s and 1930s Drinkwater lived a busy and useful public life. He belonged to many societies and committees, he travelled quite widely, he wrote a new play for Barry Jackson's new festival at Malvern (not a very good play, unfortunately), he wrote two volumes of autobiography—Inheritance (1931) and Discovery (1932); and throughout he retained to a large extent a boyish enthusiasm combined with a middle-aged worthiness. And he left behind, among a fair amount of lesser material, one extremely fine play (though just short of greatness), several short plays that ought still to be played but are not, and some poetry that still glints and gleams here and there (and was never as nerveless as its more severe critics made out). He had once been condemned by Middleton Murry (The Athenaeum, 5 Dec 1919), as being guilty of ‘a false simplicity’. The criticism is not without substance but there are among Drinkwater's various works some vivid and still-resonant exceptions. His total output amounted to seventeen plays (including an adaptation into English of a play about Napoleon by Benito Mussolini), nine volumes of verse, biographies of Pepys and Shakespeare, critical studies of Byron, Swinburne, and William Morris, and the two volumes of autobiography.

Drinkwater died at his home, North Hall, Mortimer Crescent, Maida Vale, London, of heart disease, on 25 March 1937. Several times, from quite early days onward, one finds him—in effect—writing his own epitaph, as in his poem about his family ancestors, ‘who were before me’ (Seeds of Time, 1921). The poem ‘Petition’ in the collection Olton Pools (1916) concludes:

That, when I die, this word may stand for me—

He had a heart to praise, an eye to see,

And beauty was his king.

Eric Salmon

Sources

DNB · J. C. Trewin, The theatre since 1900 (1951) · D. Perkins, A history of modern poetry (1976) · J. Drinkwater, Inheritance (1931) · J. Drinkwater, Discovery: being the second book of an autobiography, 1897–1913 (1932) · J. C. Trewin, The Birmingham Repertory Theatre, 1913–1963 (1963) · T. C. Kemp, The Birmingham Repertory Theatre, 2nd edn (1948) · G. W. Bishop, Barry Jackson and the London theatre (1933) · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1937) · b. cert. · m. certs. · d. cert.

Archives

BL, corresp. mainly with second wife, Add. MSS 62564–62567 · Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, corresp., literary MSS and papers · Indiana University, Bloomington, letters and literary papers · Ransom HRC, corresp. and literary MSS · Rutgers University, New Jersey, corresp. · Yale U., Beinecke L., papers :: BL, corresp. with Society of Authors, Add. MS 63237 · JRL, letters to Allan Monkhouse · King's Cam., memoir of Rupert Brooke · Royal Society of Literature, letters to Royal Society of Literature · Somerville College, Oxford, letters to Percy Withers · U. Leeds, letters to Sir Edmund Gosse FILM

BFINA, home footage SOUND

BL NSA, documentary recording · BL NSA, performance recordings

Likenesses

photograph, 1907 · W. Rothenstein, pencil drawing, 1917, Minneapolis Institute of Arts · W. Rothenstein, oils, c.1918, priv. coll.; on loan to NPG [see illus.] · A. Boughton, vintage bromide print, 1920–29, NPG · photographs, 1930–33, Hult. Arch. · W. Stoneman, photograph, 1931, NPG · photograph, 1933 · H. Coster, photographs, 1934, NPG · J. W. Thompson, chalk drawing, 1935, NPG · A. B. Sava, bronze head, RS · photograph (after Sava, 1931)

Wealth at death

£1577 16s. 6d.: probate, 5 May 1937, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Eric Salmon, ‘Drinkwater, John (1882–1937)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/32896, accessed 17 Oct 2017]

John Drinkwater (1882–1937): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32896

[Previous version of this biography available here: October 2009]