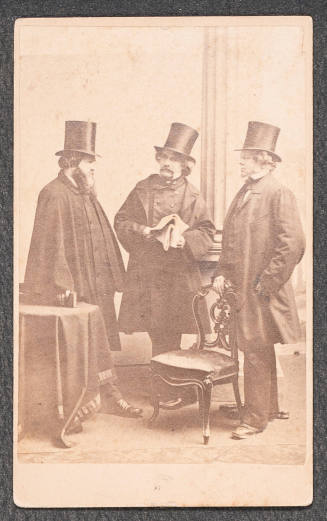

James Thomas Fields

Fields, James Thomas (31 Dec. 1817-24 Apr. 1881), publisher, editor, writer, and lecturer, was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the son of Michael Fields, a sea captain, and Margaret Beck Fields. His father died at sea before James's fourth birthday, leaving his devoted mother little more than the modest house where she raised her two sons. A gregarious and book-loving boy, James completed high school at the age of thirteen, then headed for Boston. Although college was never an option, a family friend arranged what turned out to be the next best thing: an apprenticeship with the booksellers Carter and Hendee at what is still known as the Old Corner Bookstore. Remaining at that workplace after Carter and Hendee sold out to Allen and Ticknor in 1832, and after William D. Ticknor became sole owner in 1834, the ambitious young clerk learned all about retail bookselling and brought home stacks of books to read every night. During the next few years he joined the Boston Mercantile Library Association and participated in its literary debates; he often attended plays and brought friends home to discuss them; and he regularly wrote and published poems.

Like most of his Boston counterparts, Ticknor was a bookseller who was also--if incidentally--a publisher. But in 1840 Fields began taking initiatives that would change the Old Corner's identity and his own. Conjoining his love of literature and his sound business sense, he persuaded Ticknor to publish Thomas De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and two other books by English authors requiring no royalty payments, then edited and wrote prefaces for all three. All sold well. In 1842 Fields persuaded Ticknor to publish the first authorized American edition of poems by the rising young English poet Alfred Tennyson, an authorization he secured by promising the 10 percent royalty that Tennyson wanted and a rival American publisher had refused. That volume also sold well. Another consequential initiative came in 1843. At a time when a distinctive American literature was still in its infancy and publishers were reluctant to gamble on its success, Fields persuaded Ticknor to publish John Greenleaf Whittier's Lays of My Home, and Other Poems. Again, Fields boosted a writer's income and reputation as well as the firm's.

Also in 1843, at the age of twenty-six, Fields became a junior partner in the new firm of William D. Ticknor & Company. Another man also became a partner that year--John Reed, Jr., who invested $8,000 in the firm. But "in consideration of his knowledge of the business" (to quote the articles of incorporation), Fields was required to invest only himself. Genially and shrewdly, he handled negotiations with authors and book reviewers as well as printers and bookbinders, responding to tastes that he also helped shape.

Fields broadened his participation in the world of letters in 1847 when he took his first trip abroad. To his great delight, he was welcomed into friendship by dozens of England's most eminent writers and publishers. By the time he returned to Boston, he had contracted for scores of new publications (as he would again do during all three of his subsequent trips abroad).

In 1849 Fields published his own Poems, a collection of competent verse studded with the kind of purple passages favored by period taste; it was the first of five such volumes. He also began to prepare the first collected edition of all De Quincey's work (which eventuated in twenty-three volumes). That same year Fields called on the renowned short story writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, who had just been fired from his job as surveyor of the Salem Custom House following the Whigs' presidential victory. That visit would have a major effect on Hawthorne's career and on subsequent American literary history.

Fields offered the cash-strapped Hawthorne immediate publication of anything he had ready for the press. Though Hawthorne initially protested that he had nothing to show, Fields took home an unfinished narrative that Hawthorne had expected to include in what would be his third collection of short stories. But, aware that publishing Hawthorne's first novel would be a marketing coup and that novels sold better than short stories, the publisher persuaded the author to expand his dark story of Puritan Boston into the powerful novel that is still ranked among the best that America has ever produced, The Scarlet Letter (1850). From then on, Fields was Hawthorne's devoted friend as well as his exclusive publisher, shrewdly promoting and marketing all his work and steadily encouraging him to produce more of it. And, like many other eminent American writers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Hawthorne later said that he owed his "literary success, whatever it has been or may be," to his connection with Fields.

Two major changes in Fields's life occurred in 1854. When Reed withdrew from the business, Fields became a partner in the new firm of Ticknor & Fields. That same year, at the age of thirty-seven, he entered into a remarkably happy marriage with the twenty-year-old Ann West Adams (Annie Adams Fields). Fields's marriage to Adams was in fact his second marriage. In 1844 Fields had become engaged to Mary Willard, who died of tuberculosis; six years later he married Mary's sister Eliza, who soon died of the same disease. But after a brief courtship, he married Adams, a first cousin of the Willards', whose distinguished relatives included two U.S. presidents, and who would become one of the country's most celebrated literary hostesses as well as a poet, biographer, and social reformer. They were married until his death and had no children.

During the next sixteen years, Ticknor & Fields solidified its reputation as America's most important literary publisher. The firm's list of eminent American authors included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Holmes, Emerson, James Russell Lowell, Whittier, Hawthorne, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, and its English eminences included Tennyson, Robert Browning, William Makepeace Thackeray, Charles Dickens, and George Eliot. As they all knew, Fields hired Boston's best printers and bookbinders and maintained high production standards, and no publisher was a more skillful marketer. Even writers who could command higher fees from other publishers contracted with Ticknor & Fields. For reader and writer alike, the firm's imprint was a mark of quality.

Predictably, the Old Corner Bookstore became a favorite meeting place for cultured Bostonians. Writers stopped by to see new books (their own and others') and to converse with friends (Fields among them). Fields was "the literary partner of the house," as the New York editor and critic George William Curtis wrote years later, "the friend of the celebrated circle who have made . . . Boston . . . justly renowned" ("Editor's Easy Chair," Harper's 63 [July 1881]: 305). Friends who stepped into Fields's office for a chat might be invited to dine with him at a nearby restaurant, and his hospitality dramatically increased after 1856, when he and his wife moved into the new house on Charles Street that they would occupy for as long as they lived. During a single week, the Fieldses might give a dinner party for twelve and a reception for twenty while also entertaining several houseguests.

One of the happiest years of the Fieldses' life began when they sailed for England in June 1859, a year during which they began new intimacies (with Dickens and Stowe, among others) and solidified old ones. A particularly important event of that year was Ticknor's acquisition of the Atlantic Monthly, a two-year-old "Magazine of Literature, Art, and Politics," then edited by Lowell, which had gone bankrupt. Fields immediately undertook to increase the magazine's circulation by soliciting lively manuscripts from established writers (like Hawthorne) as well as from neophytes. By the time he became editor in the summer of 1861, the Atlantic had become the country's most prestigious and influential literary periodical. Its sphere of influence extended well beyond New England, with submissions and subscriptions flowing in from New York, Ohio, California, and even London.

As editor, Fields assumed responsibility for the entire magazine, deciding what to accept or reject, what to commission or cajole, what revisions to require, and how much to pay the author. And for both author and publisher, earnings multiplied when a series of Atlantic essays or a serialized novel appeared in book form.

Major changes in the firm followed Ticknor's unexpected death in the spring of 1864. Abandoning retail bookselling, Fields sold the Old Corner Bookstore and moved into larger quarters overlooking the Boston Common. And the Atlantic editor also acquired three additional magazines--the North American Review, Our Young Folks, and Every Saturday.

Another triumph was persuading Dickens to make his second U.S. reading tour. The five-month tour that began in the fall of 1867 was enormously profitable for both the author and the publisher, as was Dickens's authorization of Fields as his exclusive American publisher. Both of the Fieldses rejoiced in their intimacy with him, an intimacy that deepened when they visited him in 1869. They were both stunned by his death the following year.

By then the Fieldses had endured another kind of grief. In 1868 the popular essayist Gail Hamilton concluded that her old friend Fields had bilked her by switching her royalty payments from a percentage basis to a unit rate, and she convinced Hawthorne's widow Sophia Hawthorne that Fields had also cheated her. Though arbiters found no legal wrongdoing, Fields's reputation was stained, a stain Hamilton spread by publishing the thinly disguised attack on him entitled The Battle of the Books (1870). Presumably that attack, his burdensome business responsibilities, and his grief at Dickens's death figured in Fields's decision to retire from publishing at the end of 1870.

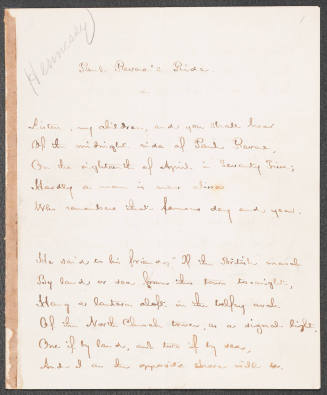

During his final decade, Fields continued to write essays and poems for the Atlantic and other periodicals--most notably essays on writers he had known that appeared first in the Atlantic and then as a volume entitled Yesterdays with Authors. He also began an enormously successful career as a lecturer. Whether he was booked into a village lyceum or a college auditorium, in Boston or the Midwest, and whether he spoke under an umbrella topic such as "Masters of the Situation" or "Cheerfulness" or focused on one of the many writers he had known and loved, Fields could be depended upon to entertain, instruct, and inspire. In 1875 his earnings enabled the Fieldses to build the summer cottage that still stands on the shores of Manchester, where they continued their long-established tradition of dispensing hospitality to their large circles of friends.

James T. Fields--the foremost publisher of good literature in mid-nineteenth-century America and one of the period's greatest magazine editors--died at Charles Street; he is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery.

Bibliography

The Fields Collection at the Huntington Library includes thousands of letters as well as notebooks, lecture notes, and other manuscripts. Other important holdings are at the Houghton Library of Harvard University, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Boston Public Library, and the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library. Fields's most important publication is Yesterdays with Authors (1872; expanded ed., 1877); Underbrush (1877) collects essays initially published in the Atlantic and other periodicals; and Ballads and Other Verses (1881) is his final collection of poems. He also produced a wide assortment of anthologies with such self-defining titles as Good Company for Every Day of the Year (1866). The three main biographies are Annie Fields, James T. Fields: Biographical Notes and Personal Sketches with Unpublished Fragments and Tributes from Men and Women of Letters (1881), W. S. Tryon, Parnassus Corner: A Life of James T. Fields, Publisher to the Victorians (1968), and James C. Austin, Fields of the Atlantic Monthly: Letters to an Editor, 1861-1870 (1953). Useful supplements include William Charvat's "James T. Fields and the Beginnings of Book Promotion, 1840-1855," included in The Profession of Authorship in America: 1800-1870, ed. Matthew Bruccoli (1968); Rosemary Fisk's unpublished 1985 doctoral dissertation, "The Profession of Authorship: Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Publisher, James T. Fields" (Rice Univ., 1984); John William Pye's James T. Fields: Literary Publisher (1987); and biographies of Annie Fields, including Rita K. Gollin's Annie Adams Fields: Woman of Letters (2002). Obituaries of Fields appeared in the Boston Transcript on 25 April 1881 and in the New York Times the following day; and "Recollections of James T. Fields" by his old friend Edwin P. Whipple appeared in the Atlantic Monthly 48 (Aug. 1881): 253-60.

Rita K. Gollin

Citation:

Rita K. Gollin. "Fields, James Thomas";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-03452.html;

American National Biography Online Jan. 2002 Update.

Access Date: Tue Oct 17 2017 15:07:16 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2002 American Council of Learned Societies. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.