Richard Watson Gilder

found: NUCMC data from Rutgers Univ. Libr. for His Papers, 1874-1949 (Gilder Richard Watson, 1844-1909)

found: WwWA, 1897-1942 (Gilder, Richard Watson; b. Bordentown, N.J., Feb. 8, 1844; mng. ed. Newark, N.J., Advertiser; later, with Newton Crane, est. Newark Register; edited Hours at Home, a N.Y. monthly; mng. ed. Scribner's Monthly, 1870; editor-in-chief, 1881, under later name The Century; pres. Public Art League of US; mem. Council Nat. Civil Service Reform League; mem. Nat. Inst. Arts and Letters; an organizer of Internat. Copyright League; chmn. N.Y. Tenement House Commission, 1894; 1st pres. N.Y. Kindergarden Assn.; v.p. and acting pres. City Club; author of poems; home N.Y.C.; d. 1909)

found: Wikipedia, website viewed Febraury 18, 2016 (Richard Watson Gilder; born February 8, 1944, Bordentown, New Jersey; died November 19, 1909; American poet and editor; journalist and editor for Newark (New Jersey) Advertiser; LLD from Dickinson College in 1883)

Gilder, Richard Watson (8 Feb. 1844-18 Nov. 1909), editor and writer, was born in Bordentown, New Jersey, the son of the Reverend William Henry Gilder, a Methodist minister and headmaster of a "Female Seminary," and Jane Nutt. Most of Gilder's early education took place in another school for girls run by his family in Flushing, New York, but all the evidence suggests a normal and happy boyhood, which included precocious interests in things literary. When only twelve, he frequented the offices of the Flushing Long Island Times and learned something of the routines of publishing, from writing and layout to the setting of type. Following the death of his father in 1864, Gilder worked for some time as paymaster on the Camden & Amboy Railroad, got a job as a reporter on the Newark Daily Advertiser, and then, in 1869, joined Robert Newton Crane, an uncle of Stephen Crane, in the founding of the Newark Morning Register.

To make ends meet, Gilder got a second job as an editor of Hours at Home, a house organ for Charles Scribner and Company. The Morning Register survived until 1878, but Gilder soon left it to concentrate on Hours at Home, becoming sole editor for 1869-1870, the last year of its life. Scribner then replaced the magazine with the much more ambitious Scribner's Monthly Magazine, hiring Josiah Gilbert Holland as editor in chief and retaining Gilder as his assistant. The magazine grew steadily from its beginnings in November 1870, until it changed its name to the Century Monthly Magazine in November 1881, when Gilder became editor in chief. For the next twenty-eight years Gilder held one of the most powerful and prestigious positions in American publishing, as the Century overtook Harper's and the Atlantic Monthly as the most popular of the taste-setting triumvirate of American monthlies.

In many ways Gilder was responsible for the magazine's success. It was he who conceived the series of personal accounts of the events of the Civil War, written by the participants, from soldiers in the skirmish lines to Generals U. S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, and published as "Battles and Leaders of the Civil War" (1884-1889). That publishing coup was followed by the serialization of John G. Nicolay and John Hay's biography of Abraham Lincoln (1890), which further contributed to the increased popularity of the magazine. With the enormous success of those series, the editors of the Century took it upon themselves to help in the development of the "New South" by publishing a series under that general title by Edward S. King (1848-1896) and then seeking out the next generation of southern writers, including Thomas Nelson Page, Joel Chandler Harris, and George Washington Cable. Indeed, Gilder seemed to view the revitalization of the South as something of a personal duty for himself and his magazine, leaving western writers to the Atlantic and English writers to Harper's.

Gilder's literary tastes were always eclectic, however. He sought the best works by the best writers of his day wherever he could find them. He took on the greater part of William Dean Howells's fictional output when Howells briefly disengaged himself from the Atlantic. He pursued Henry James (1843-1916) for contributions until the hugely unsuccessful serialization of The Bostonians. He agreed to publish excerpts from Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn as a "teaser" in the months before it was published. And while most of literary New York turned its back on Walt Whitman and his Camden coterie, Gilder welcomed his poems to his magazine and even carried around a battered copy of Leaves of Grass to read to unsuspecting philistines.

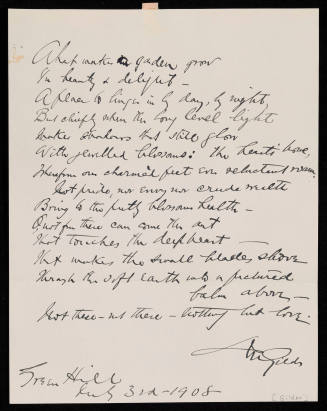

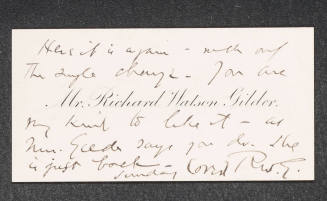

Gilder's own poetry was less successful, never rising much beyond the general mediocrity of the poetry of the day. His first volume of poems, The New Day (1875), was written under the influence of Dante's Vita Nuova (as popularized in Rossetti's English translation), and it helped him woo the young painter Helena de Kay (Helena de Kay Gilder), who became his wife in 1874; they had at least two children. Incredibly, The New Day had four editions between 1875 and 1887, several requiring more than one printing. Gilder's first collected edition of poems, Five Books of Song, had four editions between 1894 and 1900. Then, in 1908, Gilder was chosen as the first living poet to be included in Houghton Mifflin's projected series of "American Household Poets."

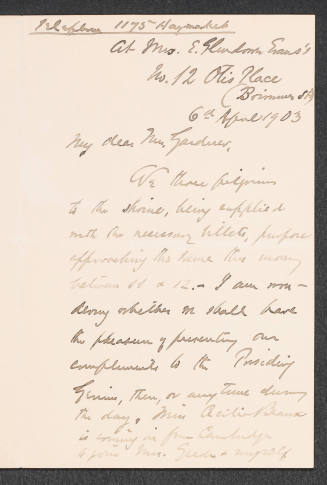

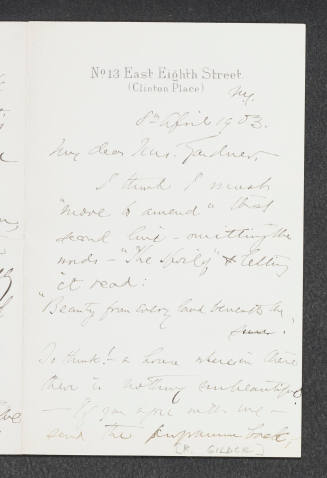

Gilder's position as the Century's editor and the respectability of his poetic output placed him in the center of the intellectual and artistic circles of New York. From their various addresses in lower Manhattan and their summer residences, first at Marion and later at Tyringham, Massachusetts, the Gilders exerted considerable influence on artistic matters. They were founding members of the Society of American Artists in 1877 and the Author's Club in 1882. Gilder was also important in many of the various reform campaigns opposed to the influence of Tammany Hall. As a personal friend of Grover Cleveland, and through long and significant participation in the American Copyright League, he was instrumental in the successful introduction of copyright legislation. Yet despite his best political intentions, Gilder sometimes found himself unable to accept the harsh realities in the world around him. For example, Gilder played an important role in cleaning up the slums of the East Side of New York City, serving in various capacities, including the chairmanship of the Tenement House Committee in 1894. Yet when Stephen Crane asked him to consider the manuscript of Maggie, a Girl of the Streets for publication in the Century, Gilder protested that it was "cruel" and gave examples of excessive detail. Crane interrupted, "You mean the story is too honest?" To his credit, Gilder nodded agreement, but Crane had to publish Maggie at his own expense. Gilder died in New York City.

Bibliography

The major manuscript sources for Gilder are the Gilder papers, Gilder letterbooks, and Century papers in the Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. Some of Gilder's letters were edited by his daughter, Rosamond Gilder, in Letters of Richard Watson Gilder (1916). A critical biography by Herbert F. Smith, Richard Watson Gilder (1970), includes a complete bibliography.

Herbert F. Smith

Back to the top

Citation:

Herbert F. Smith. "Gilder, Richard Watson";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00621.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:03:05 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.