Lucie Duff Gordon

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n82249000

Gordon, Lucie Duff [née Lucie Austin], Lady Duff Gordon (1821–1869), travel writer and translator, was born on 24 June 1821 at 1 Queen Square, Westminster, London, near the statue of Queen Anne (this section was demolished in the 1880s and renamed Queen Anne's Gate), the only child of John Austin (1790–1859), jurist, and his wife, Sarah Taylor Austin (1793–1867). Her father, author of The Province of Jurisprudence Determined (1861), was a frequent invalid, and her mother, a member of the intellectually formidable Unitarian Taylor family of Norwich, was a gifted translator. Like her mother, Lucie Austin was trained in languages, and edited or translated ten books over an eighteen-year period. As a child, she knew the fifteen-year-old John Stuart Mill, a frequent visitor to the Austin household and, along with her cousin Henry Reeve, her closest companion. Other childhood experiences included visits to Jeremy Bentham's home. In 1827 the family travelled to Bonn, Germany, in order that her father could prepare to lecture at the new University of London. Here she attended school for the first time and gained fluency in German.

On their return to England in June 1828, John Austin became ill with distress over his teaching duties and eventually resigned his post. To economize, the family moved to 26 Park Road, near Regent's Park, in the summer of 1830, the first of several moves. There they lived next to John and Harriet Taylor, and Lucie Austin renewed acquaintance with John Stuart Mill and met Thomas Carlyle. At the age of ten she was sent to a classical school in Hampstead, where, under Dr George Edward Biber, she studied Greek. When she was thirteen, the family moved to Boulogne, France, where she met Heinrich Heine. There, in August 1833, she and her mother witnessed the sinking of the Amphitrite, which was transporting convict women to New South Wales. Mother and daughter worked side by side fruitlessly trying to save those who had been washed up on the beach. Only 4 of the 131 on board survived.

On their return to London, her father once again faced career setbacks and the family moved to 5 Orme Square, near Bayswater, and then to Hastings, where Lucie Austin made friends with Janet and Marianne North. She was sent to Miss Shepherd's boarding-school in Bromley Common in 1836, when John Austin was appointed to an investigative commission in Malta. While visiting the Norths, she was baptized into the Church of England without her family's knowledge.

When Lucie Austin was seventeen she was presented to the young Queen Victoria. She married Sir Alexander Cornewall Duff Gordon, third baronet (1811–1872), on 16 May 1840, a month before her nineteenth birthday. He was ten years older and a junior clerk at the Treasury. The couple moved to 8 Queen Square, London, close to Lucie's childhood home. There she had three children, Janet Ann [see Ross, Janet Ann], Maurice, and Urania. Another boy (also named Maurice), her second child, died in infancy. The household also included Hassan al-Bakkeet from the Sudan, who had been abandoned at the age of twelve by his former master because of encroaching blindness. The Duff Gordons provided medical treatment and a home for him until his death in 1849. As a young woman, Lucie Duff Gordon was described by both Alexander Kinglake and George Meredith as quite striking, tall with dark hair and a classic, commanding profile. She was the model for the character Lady Jocelyn in George Meredith's novel Evan Harrington and possibly an inspiration for Tennyson's The Princess. Her household, a lively social centre for progressive thinkers, was often visited by Charles Dickens, William Thackeray, Sydney Smith, the Carlyles, John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor, Richard Monckton Milnes, Richard Doyle, Caroline Norton, and Tom Taylor.

Lucie Duff Gordon established a reputation for translation, starting with Wilhelm Meinhold's Mary Schweidler, the Amber Witch (1844), which she believed to be a seventeenth-century chronicle, not initially knowing it was a literary hoax. Her translation nevertheless went through three editions in 1844, and was considered superior to the original. She next was attracted to accounts of travel in the Middle East, translating The Prisoners of Abdel-Kader by M. de France (François Antoine Alby) and The Soldier of the Foreign Legion by Clemens Lamping. She also translated and condensed Paul Feuerbach's Narratives of Remarkable Criminal Trials (1846).

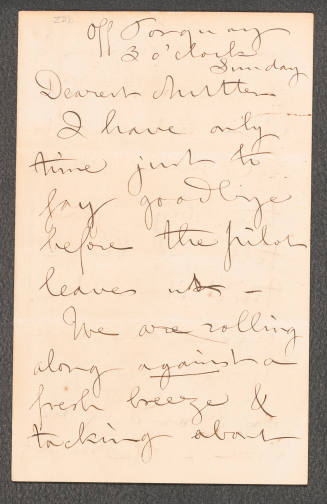

In 1851 Lucie Duff Gordon contracted tuberculosis and was forced to leave her family in search of a climate suited to her health. First she went to South Africa, and her letters home were published as Letters from the Cape (1864). In 1862, at the age of forty-one, she sailed to Egypt, where for seven years she lived in Luxor in a house built over the ruins of a temple. She wrote movingly of Egyptian village life and harshly of westernization. She was particularly critical of Viceroy Isma‘il Pasha at a time when he was seen as a progressive reformer. While the British applauded such ‘reforms’ as the building of the Suez Canal and railroads by the pasha, Lucie Duff Gordon noted the devastation brought to village life by forced labour and high taxes, necessary to support the projects. She wrote:

I care less about opening up the trade with Sudan and all the new railways ... food ... gets dear, the forced labour inflicts more suffering .... What chokes me is to hear Englishmen talk of the stick being ‘the only way to manage Arabs’ as if there could be any doubt that it is the easiest way to manage anybody, where it can be used with impunity. (Letters from Egypt, 86)

Her emphasis on common human experiences in her writing avoided stereotypes. She valued the Egyptians, ‘so full of tender and affectionate feelings’, and took her countrymen to task for their distrust of her neighbours, asking ‘Why do the English talk of the beautiful sentiment of the Bible and pretend to feel it so much, and when they come and see the same life before them[,] they ridicule it’ (ibid., 169). While her letters prophetically warned of the frustrations of the Egyptian people, they were ignored. Some of her harsher criticisms of government policy were removed in the early editions of her popular Letters from Egypt, 1863–1865 (1865) and Last Letters from Egypt (1875). While her health did improve in the dry heat of Luxor, she was only able to visit England twice. Finally succumbing to her long illness, she died in Cairo on 14 July 1869 and was buried in the city's English cemetery.

Lila Marz Harper

Sources

K. Frank, A passage to Egypt: a life of Lucie Duff Gordon (1994) · L. D. Gordon, Letters from Egypt, 1862–1869, ed. G. Waterfield (1969) · G. Waterfield, ‘Introduction’, in L. D. Gordon, Letters from Egypt, 1862–1869 (1969) · J. A. Ross, Three generations of Englishwomen: memoirs and correspondence of Mrs John Taylor, Mrs Sarah Austin and Lady Duff Gordon, rev. edn (1893) · J. Killham, Tennyson and ‘The Princess’: reflections of an age (1958) · S. Sassoon, Meredith (1948) · F. Shereen, ‘Lucie Duff Gordon’, British travel writers, 1837–1875, ed. B. Brothers and J. Gergits, DLitB, 166 (1996), 157–64

Archives

priv. coll.

Likenesses

H. W. Phillips, portrait, c.1852, NPG; repro. in Frank, A passage to Egypt · R. Cruikshank, portrait, repro. in Frank, A passage to Egypt · C. H. Jeens, stipple, BM, NPG; repro. in L. D. Gordon, Last letters from Egypt (1875) · G. F. Watts, drawing · drawing (aged eighteen), Downton House, Wales · two drawings

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice

Lila Marz Harper, ‘Gordon, Lucie Duff , Lady Duff Gordon (1821–1869)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/8175, accessed 18 Oct 2017]

Lucie Duff Gordon (1821–1869): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8175