Thomas Hood

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n80040356

found: Before I go to sleep, 1990: t.p. (Thomas Hood) jkt. (prominent English poet and editor of the first half of the nineteenth century; best known for his satirical verse, as well as several serious poems)

Hood, Thomas (1799–1845), poet and humorist, was born on 23 May 1799 at 31 Poultry, London. His father, also Thomas Hood (1759–1811), bookseller and publisher, was a Scot from Tayside. His mother, Elizabeth Sands (d. 1821), came from a well-known London family of engravers. Hood was the third of six children, the second of two sons. The family moved to Islington, then pleasantly rural. Hood attended a dame-school in Tokenhouse Yard and, later, Dr Wanostracht's Alfred House Academy in Camberwell. When Hood was twelve both his father and brother died and he moved to a modest day school run by an elderly Scot, afterwards gratefully remembered. By fourteen he was working in a City office but became ill and, possibly apprenticed to his uncle Robert Sands, or Le Keux, began to learn engraving. When his health deteriorated in 1815 he was sent north to relatives in Dundee, where he stayed for about two years. He was already writing prose and verse and contributing anonymously to local papers.

Hood returned to London in the autumn of 1817, much improved in health. He was busy engraving, working from home, and he joined a literary society. In one of his entertaining letters he wrote in 1821: ‘Truly I am T. Hood Scripsit et sculpsit—I am engraving and writing prose and Poetry by turns’ (Hood, 27). 1821 was a year of mixed fortune. His mother died. That summer, however, Taylor and Hessey (Keats's publishers) took over the London Magazine after the death of its editor in a duel. John Taylor had worked for Hood's father and invited the young Thomas to become sub-editor. Hood was in his element: ‘I dreamt articles, thought articles, wrote articles ... The more irksome parts of authorship, such as the correction of the press, were to me labours of love’ (Jerrold, 99). His career as a literary journalist had begun.

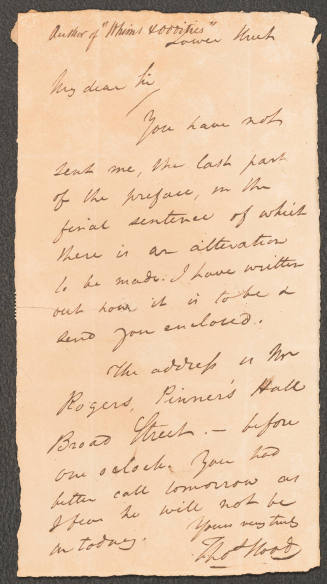

Apart from a novel, Tylney Hall (1834), some unremarkable prose, and minor writing for the stage, nearly all Hood's work, verse and prose, first appeared in magazines and annuals catering for the growing middle-class market. From 1821 to 1845 Hood was closely involved, as contributor or editor, with many of them, particularly the London Magazine, The Athenaeum, The Gem, the New Monthly Magazine, and Punch. He wrote—and illustrated, inventing visual puns—a series of Comic Annuals (1830–9), collected his magazine contributions into Whims and Oddities (1826 and 1827) and Whimsicalities (1844), and also published Hood's Magazine (1844–5). Hood wrote for a living, and was keenly alive to contemporary life and popular taste. His work provides insight into domestic reading and the development of periodical publishing in the first half of the nineteenth century.

As a young man at the London Magazine, Hood found himself ‘in rare company’: among the contributors were Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, Thomas De Quincey, and his own contemporary, Keats's friend John Hamilton Reynolds. His ‘Literary reminiscences’ in Hood's Own (1839) contain lively descriptions of the principal figures of the Romantic movement. Lamb became his mentor. In 1825 he collaborated with Reynolds in a successful volume of light satirical verse, Odes and Addresses to Great People, and published what Lamb termed his Hogarthian etching, The Progress of Cant. On 5 May 1825 he married Reynolds's sister Jane (1791–1846).

Hood's appearance accords oddly with his destined role of literary buffoon and laughter-maker: slight, unassuming, dressed in black, with what he himself on several occasions called ‘a Methodist face’ (Hood, 348). The Hoods settled at 2 Robert Street, Adelphi, London. Lamb's poem ‘On an Infant Dying as Soon as Born’ mourned their first child, but a daughter, Frances (1830–1878) [see Broderip, Frances Freeling], was born soon after they moved to Winchmore Hill; and, after they moved in 1832 to Lake House, Wanstead, a son, Tom Hood (1835–1874), was born; he was to follow his father's profession. Although constantly worried about money and health, the Hoods were a devoted, affectionate family as Memorials of Thomas Hood (1860), based on his letters and compiled by his children, testifies.

In the year Tom was born the Hoods faced financial ruin. Hood, happy in family and friends, inept or unfortunate in business dealings, invested in a publishing venture that failed. To economize and pay his debts the family moved to Koblenz in 1835; they remained in Europe for five years, the last three in Ostend. Hood worked on courageously although chronically ill. His rheumatic heart condition became much worse and he returned to London in 1840 to the care of his own doctor. The family lived first in various lodgings, finally settling at Devonshire Lodge, New Finchley Road, St John's Wood. Briefly, when he was editor of the New Monthly Magazine (1841–3), Hood's financial position improved, but became precarious again when he initiated a lawsuit over copyright (settled favourably after his death). One of Thackeray's Roundabout Papers gives a touching recollection of this ‘true genius and poet’ at this time. In 1844 several of his fellow writers, distressed by his financial hardship and rapidly deteriorating physical condition, petitioned Peel to grant him a civil-list pension; it was settled on his wife. Hood died at his London home, Devonshire Lodge, on 3 May 1845, his wife on 4 December 1846. He was buried on 10 May. In 1854 a memorial, paid for by public subscription, was erected over their grave in Kensal Green cemetery.

Hood had endeared himself to the reading public. Although his early Keatsian collection of serious verse, The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies (1827), was not well received, much in the volume was distinctive: some of the shorter poems, ‘I remember, I remember’, ‘Silence’, and ‘Ruth’, for example, have a haunting quality that places them in many anthologies. The light-hearted banter and agile puns of Odes and Addresses, however, sold well. Hood, as he frequently said, became ‘a lively Hood for a livelihood’. Years of inventive comic verse followed, its boisterous fun and terse puns uncongenial to later tastes. It does, however, exhibit Hood's extraordinary technical virtuosity in handling form, metre, and language. Here Hood is wholly individual, ‘major’ not ‘minor’, as W. H. Auden judged: ‘like nobody but himself and serious in the true sense of the word’ (Auden, 17).

Hood was never wholly clown. Light and dark coexist in his world, and often a crude reality punctures the hilarious. He wrote sombre ballads such as The Dream of Eugene Aram (1829), and tender lyrics such as ‘The Death Bed’. ‘The Haunted House’ and ‘The Elm Tree’ share contemporary taste for the macabre. Hood preferred laughter to preaching as a vehicle for social criticism: before Dickens or Thackeray the serialized, manic history of Miss Kilmansegg and her Precious Leg (1840–41) attacked with comic vigour society's vulgar display of wealth. His Ode to Rae Wilson (1837) reacted sharply to attacks on his levity, revealing the generous humanitarian impulses behind his writing: love of his fellow men, compassion, a tolerant non-sectarian Christianity, and a strong preference for a cheerful philosophy of life. Hood spoke out early against slavery, campaigned for a copyright law, and drew attention to the poor, the rejected, the oppressed, those exploited, and those harshly judged in the midst of Victorian prosperity.

Near his death Hood engaged the hearts and consciences of his readers directly in a number of poems prompted by real incidents: ‘The Song of the Shirt’ (Punch, Christmas 1843) highlighted the plight of the underpaid seamstresses of the day; in 1844 ‘The Workhouse Clock’ addressed the hardship of the poor laws; ‘The Lay of the Labourer’, the suffering of the agricultural poor. ‘The Bridge of Sighs’, the purest poem of these public verses, sprang from a newspaper report of a suicide.

In his short life Hood saw ‘Romantic’ change into ‘Victorian’: he took tea with Wordsworth, dined with Dickens. Hood's work mirrors this change. Much of his writing has intrinsic merit; some is memorable, its range impressive, its style often forward-looking, and all is valuable to anyone concerned with the transitional period, literary and social, which it reflects.

Joy Flint

Sources

W. Jerrold, Hood: his life and times (1907) · The letters of Thomas Hood, ed. P. F. Morgan (1973) · F. F. Broderip and T. Hood, Memorials of Thomas Hood, 2 vols. (1860) [rev. with additions (1884)] · J. C. Reid, Thomas Hood (1963) · J. Clubbe, Victorian forerunner: the later career of Thomas Hood (1968) [incl. The progress of cant] · W. Jerrold, Thomas Hood and Charles Lamb (1930) [repr. ‘Literary reminiscences’, from Hood's own (1839), and Lamb's reviews of The progress of cant] · L. Brander, Thomas Hood (1963) · W. M. Thackeray, ‘On a joke I once heard from the late Thomas Hood’, Roundabout papers (1863) · W. H. Auden, introduction, Nineteenth century British minor poets, ed. W. H. Auden (New York, 1966) · A. Elliott, Hood in Scotland (1885) · J. Shattock, ed., The Cambridge bibliography of English literature, 3rd edn, 4 (1999)

Archives

Col. U., Rare Book and Manuscript Library, letters · Harvard U., Houghton L., papers · Hunt. L., letters · Morgan L., papers · NYPL, papers · priv. coll. · Ransom HRC, papers · U. Cal., Los Angeles, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, papers · Yale U., Beinecke L., papers :: BL, letters to Sir Charles Dilke and Maria Dilke, Add. MS 43899 · BL, corresp. with Sir Robert Peel, Add. MSS 40553–40554, 40560 · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Bradbury and Evans · Bristol Public Library, John Wright MSS · NL Scot., corresp. · NL Scot., letters to William Blackwood and Sons · University of Bristol, de Franck MSS

Likenesses

oils, c.1832–1834, NPG [see illus.] · portrait, c.1835, NPG · T. Lewis, oils, 1838, NPG · E. Davis, bust, 1844 · M. Noble, bust on monument, 1854, Kensal Green cemetery, London · F. Croll, line engraving, BM, NPG; repro. in Hogg, Weekly Instructor · Heath, engraving (after bust by Davis), repro. in Hood's Magazine (1845) · W. Holl, stipple (after T. Lewis), BM, NPG; repro. in Hood, Complete works, ed. W. Jerrold (1935) · D. Maclise?, drawing, priv. coll. · portrait, repro. in Jerrold, Thomas Hood

Wealth at death

negligible; appears to have died in debt: Reid, Thomas Hood; Clubbe, Victorian forerunner

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Joy Flint, ‘Hood, Thomas (1799–1845)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/13681, accessed 19 Oct 2017]

Thomas Hood (1799–1845): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13681