Lewis Morris

Morris, Sir Lewis (1833–1907), poet and educationist, was born on 23 January 1833 in Spilman Street, Carmarthen, the second of the five sons of Lewis Edward William Morris (d. 1872), a prosperous solicitor, and Sophia, the daughter of John Hughes, shipowner and merchant of the same town who had made a fortune as a drysalter. His great-grandfather was Lewis Morris (1701–1765) of Anglesey, a celebrated antiquary and, in 1751, one of the founders of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion. Despite his distinguished ancestry, a fervent ‘British/Welsh’ patriotism typical of his time, and a gift for languages, Morris had very little knowledge of Welsh, for social class and a wholly English education had insulated him from the richly Welsh-speaking culture of Carmarthen town and county.

Lewis Morris was educated at the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, Carmarthen (1841–7), at Cowbridge School (1847–50), and at Sherborne (1850–51). He graduated from Jesus College, Oxford, in 1856, and was the first student in thirty years to gain first-class honours in both classical moderations and Greats; two years later he was awarded the chancellor's prize for an English essay entitled ‘The greatness and decline of Venice’. Morris was admitted to Lincoln's Inn on 21 November 1856 and called to the bar on 18 November 1861, practising mainly as an equity draftsman and conveyancing counsel in London until 1880. The work, although financially rewarding, was not demanding and, for Morris, it had the advantage of allowing him time to write.

In 1868, according to early accounts of Morris's life, he married Florence Julia Pollard (1847–1927), the 21-year-old widow of Franklyn C. Pollard of New York, but no record of the marriage has been found. It seems, rather, that during the late 1860s, while living in Hampstead, he employed Florence as a housekeeper and that, shortly afterwards, they began living together as man and wife. By 1873 they had three children, but managed to conceal their liaison from the world, not announcing their marriage until 1902. Apart from the possibility of parental disapproval, it is not known why the relationship was kept a secret for so long, but Morris may have felt that Florence's Roman Catholicism would have prejudiced his chances of a political career. It almost certainly cost him the poet laureateship, as a result of Queen Victoria's disapproval on learning that he had a common-law wife and three children. Shortly after the appointment of Alfred Austin as poet laureate in January 1896, Morris (according to one of his descendants) married Florence Pollard and ‘went to considerable pains to legitimise his children—which was successfully achieved’.

Almost from the outset Morris enjoyed immense popularity as a poet and became a well-known figure in London literary circles and in Wales. Although his first book of lyrical verse, Songs of Two Worlds (three series, 1872, 1874, 1875; new edn in one vol., 1878), was published anonymously, with the appearance of The Epic of Hades in 1877 he won immediate and widespread fame. Written, he claimed, while he was commuting to work on the London Underground, this long poem in blank verse describes a visit to the classical underworld in a series of episodes in which characters such as Tantalus, Orpheus, and Aphrodite tell their tales and the author adds comment of a moralistic nature. The book lacks vitality, its effect amounting to little more than a vague sense of moral uplift, but it ran to twenty editions (more than 50,000 copies) during the poet's lifetime and is now generally considered to be his finest work.

Morris earned his vogue as a poet by his ability to express simple truths in lucid language and traditional metre. He dispensed a cheerful optimism about this world and the next which appealed, in particular, to the morality of middle-class Victorian England. In the anonymously published Gwen (1879), which owes something to Tennyson's ‘Maud’, he traced the course of a secret marriage in a rural setting and extolled the landscape of his native county. The first book of his to appear under his own name was Songs Unsung (1883). By the year of its publication the Morris ménage was settled at Penbryn (formerly Mount Pleasant), a small mansion which the poet inherited from his father, and renamed after his illustrious forebear's old home, above the village of Pen-sarn, in the parish of Llangunnor, about a mile from Carmarthen. There he was to spend the rest of his life in comfortable circumstances and enjoying a patriarchal relationship with local people. He was, by all accounts, a tall, handsome, bearded, powerfully built man with little trace of a Welsh accent; he dressed in Welsh tweeds and had a reserved, courteous, rather patrician manner which reflected what was thought to be his shy character. Some of his critics thought him a volatile man, lacking stability and patience, especially in his professional dealings, and tending to see intrigue where none existed.

It was only in his fifties that Morris began to take an interest in the language, literature, and history of Wales. His volume Songs of Britain (1887) contains some patriotic odes such as that on the jubilee of Queen Victoria and three long poems based on Welsh legends. But for the most part he went on writing poems on classical themes, many of which are vapid outpourings remarkable more for their length and fluency than for any literary quality. His last poem of any note, A Vision of Saints (1890), which he intended to be the Christian counterpart of the pagan Epic of Hades, consists of a series of nineteen monologues by people such as Elizabeth Fry and Father Damien whom he had selected for their ‘saintly’ qualities. His other books were Songs without Notes (1894), Idylls and Lyrics (1896), Harvest Tide (1901), and The Life and Death of Leo the Armenian: a Tragedy in Five Acts. A volume of his Selected Poems appeared in 1905, and the last edition of his Collected Poems (comprising some 840 double-columned pages) in the year of his death. A selection of his prose writings, mainly essays and speeches, in which he discussed his ideals as a poet, answered some of his severest critics, and expressed his progressive views of society, appeared under the title The New Rambler in 1905.

Many of the articles in The New Rambler deal with education and other aspects of the cultural life of Wales, which became—albeit somewhat belatedly—the second great passion to which Morris devoted his energies. In 1878, encouraged by Hugh Owen, he had been appointed joint honorary secretary of the recently established University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. He threw himself into all aspects of the college's work, drafting various appeals and constitutions on its behalf, and serving as its joint treasurer from 1889 to 1896, and thereafter, until his death, as one of its two vice-presidents. He was a dedicated member of a committee appointed in 1880 to look into the state of intermediate and secondary education in Wales, which recommended the establishment of two new university colleges at Cardiff and Bangor and the passing of the vital Intermediate Education (Wales) Act of 1889. He was particularly interested in the higher education of women, whom he believed to have a moral sensibility superior to that of men. After the establishment of the federal University of Wales in 1893 he became its junior deputy chancellor (1901–3). He was a prominent member of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion and served as chairman of the council of the National Eisteddfod Association after that body had been reformed by Sir Hugh Owen in 1880.

Morris was knighted in 1895 and received the honorary degree of DLitt from the University of Wales in the year before his death. Political success eluded him, however. He was a Gladstonian Liberal in favour of home rule and the disestablishment of the Church in Wales, but he suffered from a shyness often mistaken for hauteur and was never a popular public speaker. He stood as Liberal candidate in the Pembroke Boroughs in 1886 but lost the candidature at Carmarthen in 1892 when another Liberal was appointed as the official candidate. Although he failed to achieve his ambition to enter parliament, Morris remained an active Liberal and was a member of the political committee of the Reform Club and, for several years, its vice-chairman.

Morris died at Penbryn on 12 November 1907 and was buried in the family grave in the hilltop churchyard at Llangunnor four days later. His widow died on new year's eve 1927; in her obituary no personal detail was given. During his lifetime the literary reputation of Sir Lewis Morris was second only to that of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, but soon after his death it went into rapid decline. George Saintsbury in The Cambridge History of English Literature (1916) wrote: ‘He had, sometimes, a faculty—which in a satirist, would have been admirable—of writing things which looked like poetry till one began to think of them a little.’ Although Morris had several virtues both as man and poet, from the obloquy of this harsh judgment posterity has so far resolutely declined to rescue him.

Meic Stephens

Sources

D. Phillips, Sir Lewis Morris (1981) · M. Stephens, ed., The Oxford companion to the literature of Wales (1986) · DNB · L. Morris, The new rambler (1905) · d. cert.

Archives

NL Wales, corresp., journal and papers :: BL, letters to W. E. Gladstone, Add. MSS 44390–44516 · NL Scot., corresp. incl. with Lord Rosebery · NL Wales, letters to T. C. Edwards

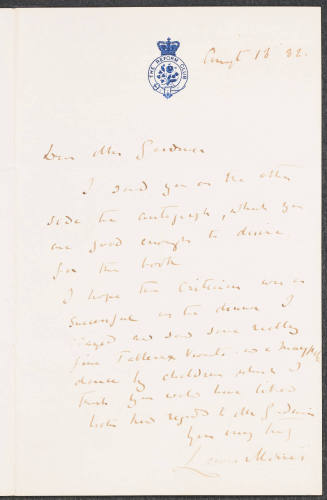

Likenesses

J. M. Griffith, finished by P. R. Montford, plaster bust, 1897–1900, NMG Wales · C. Morris, portrait, 1906; formerly at Penbryn, 1912 · W. & D. Downey, woodburytype photograph, NPG; repro. in W. Downey and D. Downey, The cabinet portrait gallery (1890) [see illus.] · H. Foulger, finished by B. A. Lewis, oils, U. Wales, Aberystwyth · W. G. John, plaster bust, U. Wales, Aberystwyth

Wealth at death

£13,416 10s.: probate, 20 Dec 1907, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Meic Stephens, ‘Morris, Sir Lewis (1833–1907)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2012 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/35114, accessed 20 Oct 2017]

Sir Lewis Morris (1833–1907): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35114