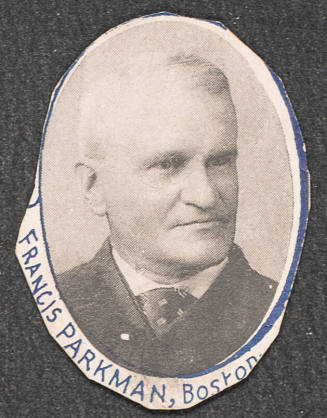

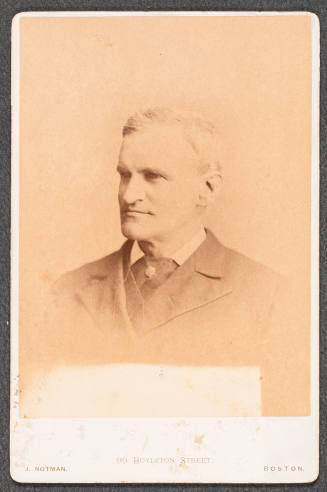

Francis Parkman

found: Amer. natl. biog. online WWW page, May 24, 2006 (Parkman, Francis (16 Sept. 1823-8. Nov. 1893), historian)

found: Wikipedia, viewed July 21, 2015 (Francis Parkman, Jr., born Sept. 16, 1823 in Boston, son of Reverend Francis Parkman Sr. (1788-1853); attended Harvard College; died in Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, Nov. 8, 1893) {https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Parkman}

Parkman, Francis (16 Sept. 1823-8 Nov. 1893), historian, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Francis Parkman, Sr., an orthodox Unitarian minister, and Caroline Hall. Parkman's paternal grandfather was Samuel Parkman, one of Boston's richest merchants. Parkman was a sickly child. His parents sought to improve his health by having him live on the Medford farm of his maternal grandfather from the time he was eight years of age until he was thirteen. When he was not attending the local school, Parkman collected bugs, eggs, rocks, and snakes, trapped small animals, and hunted birds with his bow and arrow. He also had a laboratory in a backyard shed, in which he conducted chemical experiments. In 1836 he went to live with his parents again, attended Gideon Thayer's famous private school in Boston (1836-1840), and entered Harvard College, where one of his professors was the historian Jared Sparks. Parkman interrupted his college education by taking wilderness trips in New England and an extended vacation in Europe from November 1843 to June 1844. He returned to graduate from Harvard (1844) and enroll in its law school, even though he had little interest in the profession of law. Between terms he enjoyed a rambling trip to Detroit to conduct research on Pontiac, the famous Ottawa chief. An inheritance from his wealthy grandfather made it unnecessary for him ever to work for a living.

Always determined to push himself physically to challenge chronic headaches and unsteady nerves, and in the vain hope of improving his weak eyesight, Parkman undertook a trip into the Wyoming Territory from March to October 1846. In this foolhardy but exhilarating adventure, he was accompanied by his cousin Quincy Adams Shaw. The two men explored along the California and Oregon Trail, traveling in the process from St. Louis to the environs of Fort Laramie, where they camped and hunted with the Sioux and studied frontier and Native-American tribal life. Once back in the East, Parkman found that it was most stressful to combine a modicum of law office work in New York City and steady writing of serial installments of The Oregon Trail (published in the Knickerbocker Magazine, Feb. 1847-Feb. 1849). His eyesight was so bad that he had to dictate portions of that masterpiece. He later made use of a wooden frame with wire "lines" over paper to enable him to write in semidarkness.

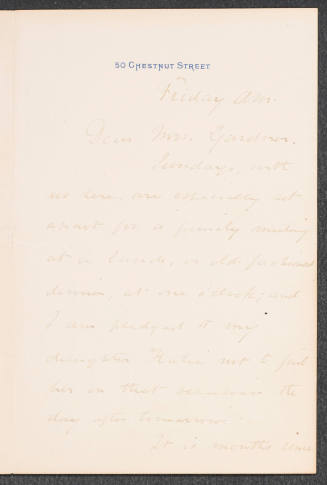

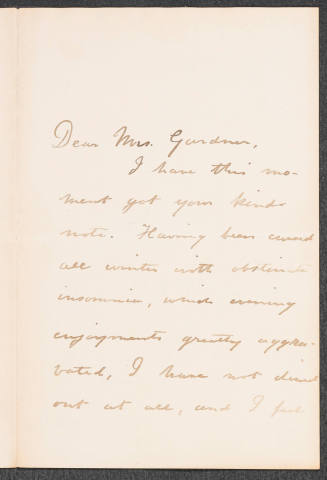

Parkman's life from this time on is a tragic but inspiring account of maladies resisted, publication often slowed but resolutely accomplished, and personal sorrows stoically met. He continued to suffer from weak eyes and blinding headaches, and later from rheumatism, indigestion, and insomnia. His phenomenal determination is suggested by the following passage in an 1849 letter to the archaeologist Ephraim George Squier: ". . . I can bear witness that no amount of physical pain is so intolerable as the position of being stranded and doomed to be rotting for year after year. However, I have not abandoned any plan, which I have ever formed and I have no intention of abandoning any until I am made cold meat of."

In 1850 Parkman married Catherine Scollay Bigelow, the daughter of Jacob Bigelow; they had three children. In 1858 Catherine Parkman died in childbirth.

In 1856 Parkman published a semiautobiographical novel, Vassall Morton, and by 1858 was deep into research for his France and England in North America. This monumental, multivolume effort was preceded by a separate work, The History of the Conspiracy of Pontiac (1851), and was concluded decades later with A Half-Century of Conflict (2 vols., 1892). The former work, revised and enlarged as The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada (2 vols., 1870), begins with an anthropological discussion of Native-American factionalism in the mid-eighteenth century, contrasts the French and the British in the New World, and then concentrates on the efforts of Pontiac to plot a concerted uprising. In all, there are seven titles in Parkman's historical series (some changed upon revision and republication) in nine volumes. Combined, they narrate the sweep of history from the sixteenth-century French pioneers in America to the epic Montcalm and Wolfe (ending with the French surrender of Canada in 1763). Parkman often traveled south and west of Boston, visited Canada at least nine times, and made research forays to England and the Continent six times. He kept splendid journals and wrote humane, detailed letters to a variety of personal and professional friends.

During the Civil War and later, Parkman sought solace by penning patriotic exhortations and by travel connected with his research (in Europe, along the eastern seaboard, and in the Midwest, Canada, upstate New York, and the Deep South). Becoming a conservative curmudgeon, he also enjoyed squabbling in print over democracy, extended suffrage, Canadian partisanship, and educational policies. At one time, when illness kept him from pursuing historical research and writing, he read scientific treatises on horticulture, supervised the preparation of a sixty-by-forty-foot garden and the construction of a greenhouse over it, and tended roses, lilies, and other blooms--often while in his wheelchair. He even developed the Lilium parkmanni and sold it to a British specialist. He also published a little handbook entitled The Book of Roses (1866), to share his successful techniques with fellow rosarians. Most important, to the end of his life, he continued updating and revising many of his historical volumes in an effort both to be accurate and also to heighten their overall unity. When his daughters wanted to get married, he gathered recommendations concerning their would-be fiancés and interviewed them narrowly. (Both young men became excellent sons-in-law.) Shortly after his seventieth birthday, Parkman succumbed to appendicitis and accompanying peritonitis and died in Boston.

Parkman is revered to this day for his Oregon Trail and for his splendid historical volumes. In its final form The Oregon Trail (entitled The California and Oregon Trail in 1849 and then Prairie and Rocky Mountain Life in 1852, before it took on its present title in 1872) is valuable for three main reasons. First, it accurately reports the observations of a daring young man from the East on a western trek three years before the gold rush of 1849 made Americans more interested in the Far West. Second, it is a fascinating chapter in the life of one of America's foremost historians, depicting freedom from the confining East and exploits on the Great Plains and in the Rocky Mountains. Parkman's bracing account bears comparison with the best of American nonfictional, book-length narratives, including, for example, Richard Henry Dana, Jr.'s Two Years before the Mast, Henry David Thoreau's Walden, Mark Twain's Roughing It, and Ernest Hemingway's Green Hills of Africa. And third, The Oregon Trail displays enduring, organic literary art. It has a sonata-like form: the young hero, as in a myth, leaves the known East; steps across the threshold into the unknown; meets several challenges while living with Native Americans; observes, becomes experienced, then almost sadly begins his return; and at last tries to go home again but finds himself permanently changed. Chapter 14, "The Ogillallah Village," is central to the subtly balanced, 27-chapter structure and thus functions as the keystone of the entire architecturally balanced work.

The Oregon Trail combines realism and romanticism: Parkman records data of Native-American camps, rituals, weapons, and hunting methods--in part to prepare himself for his later historical accounts of tribal allies and enemies of the French and English. More romantically, he lavishly describes the untainted beauty of western nature. He also admires mountain men, trappers, and guides, not to mention a noble Native American or two. Returning to eastern reality literally sickened Parkman.

It is less for The Oregon Trail, however, than for France and England in North America (9 vols., 1865-1892) that Parkman is extolled. Its volumes appeared thus: part 1, chronologically, of the series was Pioneers of France in the New World (1865; rev. ed., 1885); part 2, The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century (1867); part 3, The Discovery of the Great West (1869; rev. ed., La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West, 1879); part 4, The Old Régime in Canada (1874; rev. ed., 1894); part 5, Count Frontenac and New France under Louis XIV (1877); part 6, Montcalm and Wolfe (2 vols., 1884); and part 7, A Half-Century of Conflict (2 vols., 1892).

As for chronology, Pioneers of France concerns both the Huguenots' abortive settlement efforts in opposition to the Spanish in what is now Florida and also the heroic efforts of Samuel de Champlain to establish a foothold in what is now Canada. The Jesuits details the efforts of French Jesuit priests to Christianize Native Americans southwest of Quebec from about 1632 to 1670. La Salle is a thrilling narrative of the finding by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle of the Mississippi River and of his attempt to colonize the region for the glory of France and Louis XIV. The Old Régime is an anthology of essays on the religious, political, and social problems arising from efforts of the French to colonize eastern Canada from the 1630s to 1763. The central figure of Frontenac is Louis de Buade, Comte de Palluau et de Frontenac, a military courtier who became governor of Canada; Parkman especially relishes this brilliant, irascible leader. In the preface to his next title, Montcalm and Wolfe, the aging historian proudly explains his life's work:

The plan . . . was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. . . . These . . . volumes are a departure from chronological sequence. The period between 1700 and 1748 has been passed over for a time. When this gap is filled, the series of "France and England in North America" will form a continuous history of the French occupation of the continent.

Eight years later, Parkman put the last piece in place with A Half-Century of Conflict.

Most of the volumes of his history proved immensely popular. Pioneers of France and The Old Régime, for example, went into more than twenty editions each. La Salle, Montcalm and Wolfe, and Pontiac are especially admirable for their scholarly accuracy and painterly descriptions and for a narrative momentum reminiscent of Sir Walter Scott and James Fenimore Cooper.

Throughout the series, Parkman steadily dramatizes the physical hardihood evinced by his particular heroes when challenged by the big woods and big waters and when subduing military opposition. He praises the first settlers' moral strength in overcoming what he describes as barbaric Indian ferocity, and he portrays forward-looking British political liberty as defeating reactionary French theocratic absolutism. Examples abound. La Salle, whom Parkman calls "a grand type of incarnate energy and will," explored the Mississippi River again and again, literally canoeing hundreds upon hundreds of miles, tried to colonize what is now Texas, and was murdered by his own mutinous men. Parkman, who saw dualisms almost everywhere, explains that La Salle's "firmness, his courage, his great knowledge . . . and his untiring energy" were tragically "counterbalanced by a haughtiness of manner which often made him insupportable, and by a harshness towards those under his command which drew upon him an implacable hatred, and was at last the cause of his death." Still, the historian must express his admiration, and perhaps a touch of envy: "That very pride which, Coriolanus-like, declared itself most sternly in the thickest of the press of foes, has in it something to challenge admiration. Never, under the impenetrable mail of paladin or crusader, beat a heart of more intrepid mettle than within the stoic panoply that armed the breast of La Salle." When General James Wolfe, though dangerously ill in August 1789, retains his unsleepingly firm purpose, Parkman images the situation thus: ". . . as the needle, though quivering, points always to the pole, so, through torment and languor and the heats of fever, the mind of Wolfe dwelt on the capture of Quebec." Parkman found little in Native Americans to his liking and, in Jesuits, spills much graphic ink in depicting the torture of Father Jean de Brébeuf and also the Oneida war chief Ononkwaya, who, though burned with live coals and with his hands and feet cut off, crawled forward to snarl at his red-skinned torturers to the end.

Parkman sets his character portrayals, as well as his dramatic narrative events, against a panoramic backdrop of such sacred coloration that one wonders whether he was not sorry that Europeans ever found and exploited the early American Eden. He knew nature in its varied moods, having hunted in rugged New England forests, camped along the Oregon Trail, and taken primitive means of transportation to numerous military outposts in search of archival materials. He had a true poet's ability to strip away the crusts of so-called civilization and imagine what America was like before it had been damaged by explorers, pioneers, settlers, soldiers, and other exploiters. He had a poet's pen as well: ". . . in the morning they embarked again, [and] the mist hung on the river like a bridal veil, then melted before the sun, till the glassy water and the languid woods basked breathless in the sultry glare" (La Salle). His humor could be simple, irreverent, or mordant. When a group of hospitable Native Americans entertain a Jesuit visitor, they "shared the feast together, his entertainers using as napkins their own hair or that of their dogs" (Jesuits). When New England artillerymen fire at Quebec's cathedral spire, we read this: "The Puritan gunners wasted their ammunition in vain attempts to knock it down. That it escaped their malice was ascribed [by the French] to miracle; but the miracle would have been greater if they had hit it" (Frontenac). As for certain unprepared French soldiers housed in Quebec, "lighted hand-grenades down the chimney, . . . exploding among the occupants, told them unmistakably that something was wrong" (Frontenac).

Francis Parkman was a great historian, squarely in the romantic narrative tradition. He belongs in the select company of George Bancroft, John Lothrop Motley, and William Hickling Prescott. Only the later Henry Adams, who was nonromantic in the extreme, can vie with Parkman for preeminence among nineteenth-century American historians. In the twentieth century, Samuel Eliot Morison qualifies as perhaps best for continuing in Parkman's grand tradition. Parkman is a timeless example for treating historical material with respect; for familiarizing himself with the topography of pertinent locales; and for being impartial in handling rival combatants, politicians, and religious leaders. He developed the rich style of an accomplished novelist. He employs the eyewitness point of view, sharpens it with pictorial and dramatic effects, and often includes ironic, theatrical asides.

Parkman has been criticized for routinely trumpeting the victory of progressive Protestantism over conservative Catholicism. This interpretation, however, is shallow. In truth, Parkman extolled French Huguenot seriousness and honor, admired the tough and perseverant French explorers, tried to come to terms with Native-American pagan stoicism, saw grim good in admittedly opportunistic Jesuits, admired British colonial policy and democratic decency, and emulated old New England energy but not its intolerance. He inveighed against Spanish treachery, French hypocrisy, British stolidity, Native-American cruelty and perfidy, and above all man's inhumanity to man and the despoilation of nature. It seems tempting to conclude, therefore, that the overarching message in Parkman's historical writings is a lament--that his beloved wilderness had lost the most by the time the long conflict ended in the New World. What remains, however, long after a careful reading of Parkman's stupendous France and England in North America is the picture of a pain-wracked, grimacing old historian savoring the exploits of his five favorite soldierly heroes--Champlain, Frontenac, La Salle, Pontiac, and Wolfe--and, like them, never giving up.

Bibliography

Most of Parkman's papers are located in the Houghton and Widener libraries of Harvard University, the Harvard Archives, and in the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. Repositories, among several others, also containing Parkman material are the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; the Library of Congress; the Detroit Public Library; the Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.; the State Historical Society of Wisconsin; and the Seminary Archives, Laval University. Francis Parkman, France and England in North America, ed. David Levin (2 vols., 1983), provides a detailed chronology. The Journals of Francis Parkman, ed. Wade Mason (2 vols., 1947), and Letters of Francis Parkman, ed. Wilbur R. Jacobs (2 vols., 1960), illuminate Parkman's personal and professional life. The best biography of Parkman is Mason Wade, Francis Parkman: Heroic Historian (1942; repr. 1972). The most substantial critical studies are Otis A. Pease, Parkman's History: The Historian as Literary Artist (1953; repr. 1968); Howard Doughty, Francis Parkman (1962); and Wilbur R. Jacobs, Francis Parkman, Historian as Hero: The Formative Years (1991). A useful short work is Robert L. Gale, Francis Parkman (1973), which stresses Parkman's literary qualities. The best comparative studies are David Levin, History as Romantic Art: Bancroft, Prescott, Motley, and Parkman (1959), and Richard C. Vitzthum, The American Compromise: Theme and Method in the Histories of Bancroft, Parkman, and Adams (1974). Gregory M. Pfitzer, Samuel Eliot Morison's Historical World: In Quest of a New Parkman (1991), places Parkman in the tradition of great narrative historians and identifies Parkman as the historian Morison's ideal and model.

Robert L. Gale

Back to the top

Citation:

Robert L. Gale. "Parkman, Francis";

http://www.anb.org/articles/14/14-00463.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 12:31:04 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.