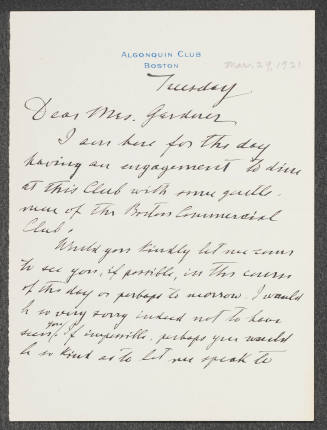

Roman Romanovich Rosen

Russian embassador to the U.S. in 1917

Baron Roman Romanovich Rosen (Russian: ????? ????????? ?????) (February 24, 1847 – December 31, 1921) was a diplomat in the service of the Russian Empire.

Contents [show]

Biography[edit]

Rosen was from a long line of russified Baltic German nobility (with a Swedish title, obtained when Livonia and Pomerania were Swedish territories) that included musicians and military leaders. One of his ancestors, another Baron Rosen, won distinction in command of the Astrakhanskii Cuirassier Regiment at the Battle of Borodino on September 7, 1812 for which he was noted in the official battlefield report to General Barclay de Tolly.[1] A Washington Post article dated July 5, 1905 claimed that, "Baron Rosen is of Swedish ancestry, his forebears having followed Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus in his invasion of Russia and settled there. He was chargé d'affaires at Tokyo and later at Washington, and was acting in a judicial capacity as the mouthpiece of an international tribunal that was regarded as discourteous to Japan. ... As judicial minister, he reformed the judicial system of Siberia." Actually, the family was originally from Bohemia (Habsburg territory) and included one Marshal of France and one Austrian Field-Marshal. Rosen’s mother was a Georgian, Elizabeth Sulkhanishvili.

Early career[edit]

Rosen graduated from the University of Dorpat and the Imperial School of Jurisprudence,[2] and joined the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Asiatic Department, rising to head the Japan Bureau in 1875. He helped draft the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1875), in which Japan exchanged its claims over Sakhalin for undisputed sovereignty over the entire Kurile islands chain.[2] He served as First Secretary of the Russian legation at Yokohama from 1875-1883. Rosen was then appointed to the Consulate-General of Russia in New York City in 1884, and then as temporary charge d’affairs to Washington DC from 1886-1889. In 1891, he opened the Russian legation in Mexico City, remaining in Mexico until 1893. He then returned to Europe, and was appointed ambassador Serbia, staying in Belgrade until 1897.[2]

Career in the Far East[edit]

During a short term as Russian minister to Tokyo in 1897–1898, Rosen concluded the Nishi-Rosen Agreement between Russia and Japan, whose articles recognized Japanese supremacy in Korea in exchange for an implicit recognition of Russia's exclusive rights to the Kwantung Leased Territory.[2] However, after he was publicly critical over increasing Russian military activity on the Korean coast and the Yalu River, he was suddenly transferred to the rather symbolic post as Ambassador of Russia to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1899. In 1900 his diplomatic career revived when he exchanged Munich for Greece, and in April 1903 his most important period commenced when he was reinstalled as Minister in Tokyo. Rosen was in Tokyo at the start of the Russo-Japanese War, which he had made every effort to prevent. When United States President Theodore Roosevelt attempted to mediate the hostilities, Rosen was chosen as new Russian ambassador to the United States in May 1905 and as Sergei Witte's deputy within the Russian peace delegation. Rosen traveled to New Hampshire for negotiations in a cessation of hostilities and a peace treaty. The resulting Treaty of Portsmouth was a diplomatic triumph, which ended the war on very favorable terms for Russia.[3]

Negotiating the Treaty of Portsmouth (1905) – from left to right: the Russians at far side of table are Korostovetz, Nabokov, Witte, Rosen, Plancon; and the Japanese at near side of table are Adachi, Ochiai, Komura, Takahira, Sato. The large conference table is today preserved at the Museum Meiji Mura in Inuyama, Aichi Prefecture, Japan.

Later career[edit]

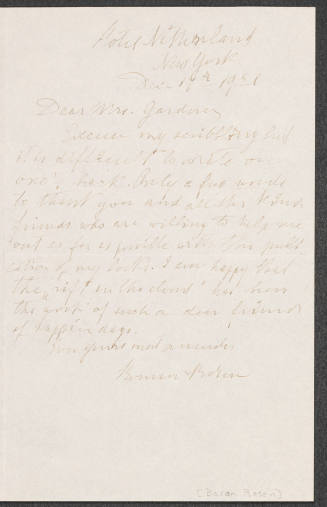

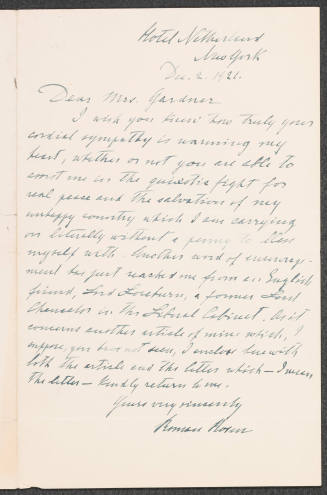

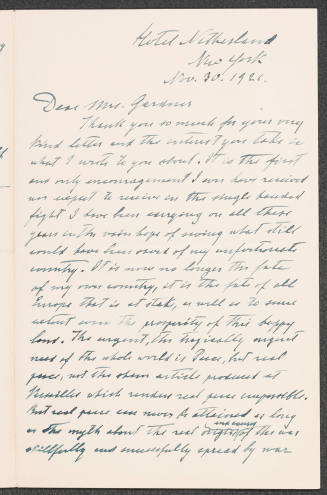

Rosen stayed in the United States until autumn 1911, when he was recalled to St. Petersburg to retire from the diplomatic service. He was subsequently appointed by Tsar Nicholas II to the State Council of Imperial Russia. He held this membership in the Russian parliamentary Upper House under the Constitution of 1905 until the overthrow of the monarchy by the February Revolution in 1917. After the Bolshevik takeover in November 1917 October Revolution and the subsequent persecution of the old political and social elites, Rosen and his family managed to escape from Russia with the help of Western diplomatic friends in the end of the year 1918. He spent his last years in poverty, working as a translator and business consultant.[2]

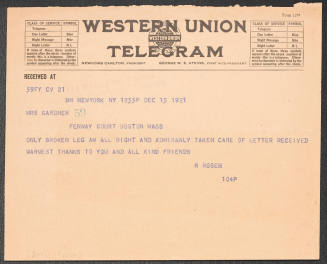

He got hit by a taxi while walking down the street on the night of December 14, 1921 in Manhattan, New York City.[4] This accident resulted in the fracture of his shin bone, and despite the fact that he was initially "cheerful[ly] unconcern[ed]" about this accident, Rosen died due to lobar pneumonia resulting from this accident on December 31, 1921, a little more than two weeks after this accident occurred.[2][4]

Legacy[edit]

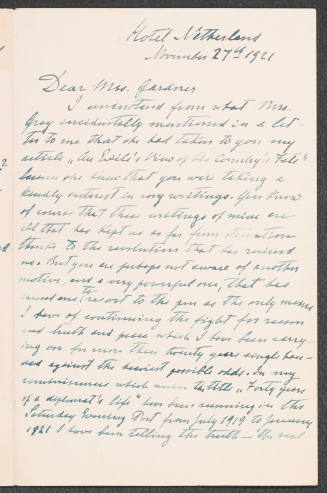

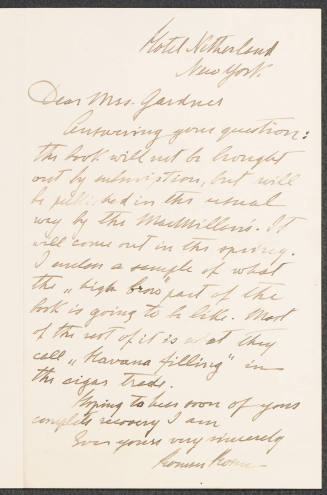

Rosen wrote a series of articles about European diplomacy and politics for The Saturday Evening Post covering the period from his first exile in Sweden to his life in the United States. The series was published in 41 parts from 1919–1921, and was posthumously issued as a 2-volume-book "Forty Years of a Diplomat's Life" in 1922.

Awards[edit]

Order of Saint Stanislaus Ribbon.PNG Order of St. Stanislaus, 1st degree, (1894)

Order of Saint Anne Ribbon.PNG Order of St. Anne, 1st degree (1898)

Saint vladimir (bande).png Order of St Vladimir, 2nd degree (1900)

Order of the White Eagle War Merit ribbon.jpg Order of the White Eagle, (1897)

Band to Order St Alexander Nevsky.png, Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, (1911)

Notes[edit]

Jump up ^ The report is available online

^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, p. 359-323-324.

Jump up ^ "Text of Treaty; Signed by the Emperor of Japan and Czar of Russia," New York Times. October 17, 1905.

^ Jump up to: a b "Baron Rosen Dies after Auto Injury. Ex-Russian Ambassador, 74, Whose Shin Bone Was Broken, Succumbs to Pneumonia. Struck Down On Dec. 14 One of Envoys Who Settled War Between Russia and Japan - Was a Diplomat for Forty Years. .." New York Times. 1922-01-01. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

References[edit]

Davis, Richard Harding, and Alfred Thayer Mahan. (1905). The Russo-Japanese war; a photographic and descriptive review of the great conflict in the Far East, gathered from the reports, records, cable despatches, photographs, etc., etc., of Collier's war correspondents New York: P. F. Collier & Son. OCLC: 21581015

Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5: The Scarecrow Press.

Korostovetz, J.J. (1920). Pre-War Diplomacy The Russo-Japanese Problem. London: British Periodicals Limited.

External links[edit]

The Museum Meiji Mura

online A bibliography of Rosen's articles in The Saturday Evening Post

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Rosen I.S. 1/5/2018

https://www.worldcat.org/identities/lccn-no00051809/ I.S. 1/5/2018