Richard P. Strong

Fortress Monroe, Virginia, 1872 - 1948, Boston

He was born in 1872, earned his medical degree at Johns Hopkins University and died in Boston on July 4, 1948.[1] wikipedia accessed 10/23/2017

Strong, Richard Pearson (18 Mar. 1872-4 July 1948), medical scientist and the first professor of tropical medicine at Harvard University, was born at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, the son of Richard P. Strong, a colonel in the U.S. Army, and Marion Burfort Smith. After attending the Hopkins Grammar School of New Haven, Connecticut, Strong enrolled at Yale University, having as his goal the study of medicine. As an undergraduate, Strong worked in the laboratories of Russell Chittenden, professor of physiological chemistry at the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, where he became excited at the prospect of applying new methods of precision and accuracy to medical diagnosis. He graduated in 1893, after completing a senior thesis on cholera.

Strong spent much of the following summer discussing which medical school to attend with pathologist William Welch while working in Welch's laboratory at the Johns Hopkins University. That fall Strong enrolled at Hopkins, which was then developing a reputation as the premier institution of scientific medicine in the country. Impressed by the clinical teaching of William Osler, Welch, and William Thayer, Strong was likely to be found with his microscope on the wards, where he occasionally detected obscure cases of malaria. Finding a parasite that no one had seen before, he identified it from a textbook as Strongyloides intestinalis and brought the specimen to Washington, D.C., where C. W. Stiles of the Army Medical School confirmed his diagnosis. "It then dawned on me," Strong later recalled in a letter to Johns Hopkins Medical School professor Alan M. Chesney, "that there did not seem to be anyone in this country who had devoted himself to the study of tropical diseases as a specialty, and I therefore decided to make this field my life work."

It proved a timely decision. After graduating in 1897 in the first Hopkins medical class and finishing his residency training at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Strong soon had an opportunity to acquire as much clinical and laboratory experience of tropical disease as he could wish. The Spanish-American War, and the subsequent annexation of a tropical empire, signaled a new demand for tropical expertise in the American medical profession. As first lieutenant and assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army, Strong was sent in 1899 to Manila, where he established and directed the Army Pathological Laboratory and was appointed to preside over the Army Board for the Investigation of Tropical Diseases in the Philippine Islands. He spent the next fourteen years studying tropical disease in the archipelago.

In 1902, at the request of Dean C. Worcester and Paul C. Freer, who were organizing civil scientific work in the Philippine Islands, Strong resigned from the army to become director of the biological laboratories of the Bureau of Science in Manila. The next year, in order to catch up with developments in bacteriological technique, Strong visited Germany, where he investigated cholera vaccines in the laboratories of Robert Koch and Paul Erlich. (As a result of this contact, Erlich later sent Strong some of the first specimens of Salvarsan or 606, which Strong used with dramatic success in the treatment of yaws.) On his return to the islands less than a year later, Strong resumed his duties at the biological laboratories, where he continued to experiment with cholera vaccines and began new studies of plague, dysentery, and beriberi. While much original work was accomplished--all of it published initially in the Philippine Journal of Science--Strong was often in despair, faced with adverse tropical conditions and difficulties in acquiring adequate equipment and appropriately trained American scientists. Original research was repeatedly frustrated by the demands of service work for the Bureau of Health, which, under Victor G. Heiser, its single-minded director, was attempting vigorously to suppress epidemic disease in the archipelago.

The Bureau of Science conducted many of its clinical trials of biological products on inmates of Manila's Bilibid Prison. In November 1906 Strong inoculated twenty-four men with a live cholera vaccine that had accidentally become contaminated with plague bacilli; thirteen subjects later died. Strong became despondent over the disaster--Freer described him as "pretty near crazy"--and offered to resign, but James F. Smith, the governor-general of the Philippines, instead appointed a general committee to investigate the incident. The committee criticized Strong for his failure to obtain voluntary consent from the prisoners and for the sloppy care of his incubators; but the attorney general found him innocent of criminal negligence, and the governor-general accordingly exonerated him.

Strong soon recovered from his humiliation. In 1907 he added an appointment as professor of tropical medicine at the new University of the Philippines to his duties at the Bureau of Science. In 1910 he also took over as chief of the medical department of the Manila General Hospital and organized the first meeting of the Far Eastern Association of Tropical Medicine.

Strong became a prominent and busy member of American colonial society. In 1901 he had married a recently divorced Englishwoman, Eleanor E. Mackay, but they separated within the year. Like many men in the islands, Strong demonstrated a passion for sport: he excelled at lawn tennis, was a keen hunter, and a dashing number one on a crack polo team. His consolation at the end of a hard day's work was to play a Beethoven sonata on his violin. When W. Cameron Forbes, later a governor-general of the islands, met Strong in 1905, he described him in his diary as "quite fat, also bald, and very suave and doctorial, Johns Hopkins, friend of Osler and Will Thayer, previously Yale, but a good fellow in spite of that and certain lingering Yaleness." In the small American community, it was Strong's conventional "doctorial" quality that was most admired.

In 1911 the American Red Cross and the War Department selected Strong to study the origins of an epidemic of pneumonic plague in Manchuria. In temperatures well below zero, and with few facilities and no effective precautions against the disease, Strong managed to determine that the epidemic's source was the tarbagan, an Asian marmot, and that the plague bacillus was airborne. His research and his prominent role at the international conference in Mukden secured his international reputation as Walter Reed's successor to the title of America's foremost expert on tropical diseases. In 1912 Johns Hopkins tempted Strong with a lectureship in tropical medicine, but the following year he accepted Harvard's first chair in the subject. Frederick C. Shattuck, the Jackson professor of clinical medicine at Harvard, had recruited Strong on the recommendation of his son, George C. Shattuck, who had spent three months in Strong's laboratory in 1907. Frederick Shattuck and Cameron Forbes both contributed money to help establish the position. In announcing the appointment, the Harvard Alumni Bulletin praised the university for taking up its part of the "white man's burden."

For the next twenty-five years, Strong presided over tropical medicine at Harvard. As finances became scarce, he deferred indefinitely his plan to build up a school to rival those of London or Liverpool; Harvard's School of Public Health took over the department in 1922, and with Strong's retirement in 1938, the subject was merged with comparative pathology. Nevertheless, Strong and his colleagues, including George Shattuck, Andrew W. Sellards, and Hans Zinsser, conducted extensive investigations of tropical problems. Strong himself led expeditions to Central and South America, Serbia, and central and southern Africa. His more important discoveries were the causes of oroya fever and the vector of onchocerciasis, or "river blindness." Most of these journeys were long and arduous: in order to survey the diseases of Liberia in 1926, Strong had crossed the country three times on foot, and he later walked across Africa from west to east. During this expedition he suffered terribly from heat and exhaustion, losing over forty pounds in weight. He continued, though, to play his violin at the conclusion of each day's walk. He undertook his last expedition at the age of sixty-two.

Strong made distinguished contributions to medical care during both world wars. In 1917 he joined the medical corps at Harvey Cushing's Base Hospital No. 5, rising through the war to the rank of colonel. For his contributions to the discovery of the cause of trench fever, Strong was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, while the British made him a Companion of the Bath, and the French installed him as an Officier de Légion d'honneur. Immediately after the war, Strong took charge of medical research for the American Red Cross. Active in the formation of the League of Red Cross Societies in 1919, Strong became, for a year, the first director of the medical section of the league. In the Second World War, at the age of sixty-nine, Strong again volunteered for service and so finished his career where he had been first inspired to begin it: at the Army Medical School, teaching tropical medicine to young physicians eager to identify parasites. During the 1940s, Strong also revised E. R. Stitt's standard textbook on tropical medicine.

Strong was president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine (1914), the Association of American Physicians (1925-1926), the American Society of Parasitologists (1927), and the American Academy of Tropical Medicine (1936). He was a trustee of the Carnegie Institution and a member of many scientific societies. In 1939 he received the Theobald Smith Medal of the American Academy of Tropical Medicine. When the American Foundation of Tropical Medicine established the Richard Pearson Strong Medal in 1943, its first recipient was Strong himself.

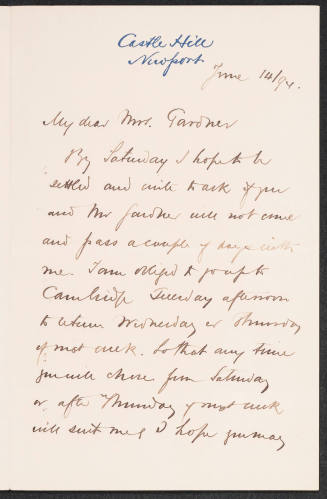

Strong's second marriage in 1916 to Agnes Leas Freer had ended in divorce. In 1936 he married Grace Nichols, who died in 1944. None of his marriages produced children. Strong, who in the past had been extremely gregarious, entertaining friends at his houses in Boston and Newport, Rhode Island, or at his many clubs (sixteen in the United States alone), withdrew from social life after the death of his third wife. He died in Boston after a protracted and painful illness. In 1952 the Belgian government endowed the Richard Pearson Strong chair of tropical medicine at the Harvard School of Public Health. Strong, a leader of the first generation of American medical scientists to receive rigorous laboratory training, contributed more than anyone else to the establishment of research and education in tropical medicine in the United States.

Bibliography

Strong's papers are located chiefly at the Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives at the Johns Hopkins University holds some interesting letters. Also relevant are the papers of W. Cameron Forbes at the Houghton Library, Harvard University. E. Waldo Forbes, "Richard Pearson Strong," in his Saturday Club: A Century Completed (1958), is an important source. See also Arthur S. Pier, American Apostles to the Philippines (1950); G. C. Shattuck, Tropical Medicine at Harvard (1954); and two articles by Eli Chernin, "Richard Pearson Strong and the Iatrogenic Plague Disaster in Bilibid Prison, Manila, 1906," Reviews of Infectious Diseases 11 (1989): 996-1004, and "Richard Pearson Strong and the Manchurian Epidemic of Pneumonic Plague, 1910-1911," Journal of the History of Medicine 44 (1989): 296-319.

Warwick Anderson

Back to the top

Citation:

Warwick Anderson. "Strong, Richard Pearson";

http://www.anb.org/articles/12/12-00891.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:23:44 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1890 - 1957, Big Sur, California

Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 1835 - 1910, at sea aboard the RMS Adriatic

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Preston, Lancashire, England, 1859 - 1907, London

New York, 1851 - 1934, New York

Ledbury, England, 1878 - 1967, near Abingdon, England

Boston, 1818 - 1890, Newton, Massachusetts