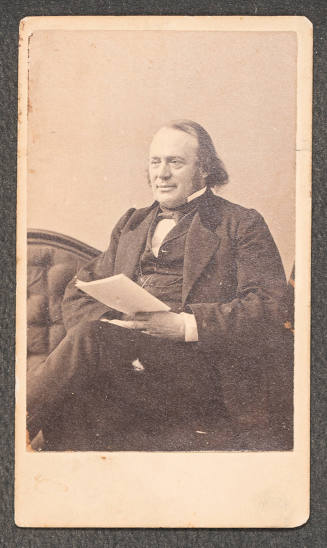

Louis Agassiz

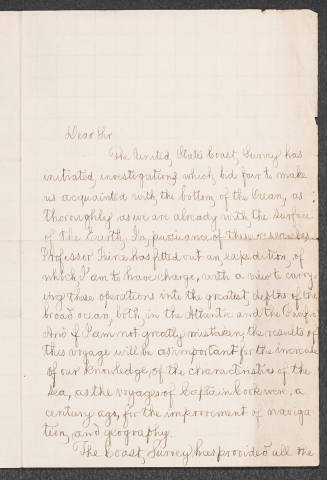

Agassiz, Louis (26 May 1807-14 Dec. 1873), zoologist and geologist, was born Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz in Motier, Switzerland, the son of Rodolphe Agassiz, a Protestant pastor, and Rose Mayor. Louis early in life spurned family pressure to become a businessman and planned to devote himself to the professional study of nature. At the age of twenty-one he predicted he would become "the first naturalist of his time, a good citizen and a good son. . . . I feel within myself the strength of a whole generation to work toward this end" (Lurie [1960], p. 31).

Such determination gained for Agassiz a superior education in the natural sciences. At the Universities of Heidelberg and Munich, and in the city of Paris, Agassiz's career was molded by contacts with leading men of science and philosophy. Naturalist Johann B. Spix allowed him in 1829 to publish a collection of the fishes of Brazil that Spix had made. Anatomist Ignaz Döllinger trained him in the use of the microscope and introduced him to the new and exciting science of embryology. Lorenz Oken's philosophy emphasized the romantic and idealistic significance of nature study.

Agassiz came to be identified with two distinct and often contradictory views of natural history, one precise and pragmatic, the other transcendental. This dualism was represented in the work of French anatomist Georges Cuvier who, knowing Agassiz in Paris, turned over to him his notable collection of fossil fish depictions and, with it, a view of nature that, while exact, also extolled the grandeur of the creative act. Geographer Alexander von Humboldt, adviser to the king of Prussia, was similarly charmed by Agassiz's intelligence and in 1832 arranged for a professorship for him at the Collège de Neuchâtel in Switzerland. In Carlsruhe Agassiz met and married in 1833 Cécile Braun. The two took residence in a small Neuchâtel apartment, soon filled by the arrival of three children.

Agassiz's Neuchâtel years were the most productive of his life, encompassing extraordinary activity in teaching, research, and instilling interest in natural history in the townsfolk. Aided by funds from European scientific societies, Agassiz spent 1832-1842 studying the fossil fish collections in museums and private holdings throughout Europe. The result was the six-volume Poissons fossiles, a study of more than 1,700 ancient fishes analyzed by the comparative method first taught by Cuvier. Unsurpassed in the nineteenth century, the study was the basis of Agassiz's fame and scientific fortune. It won high praise from distinguished naturalists such as Sir Charles Lyell and Richard Owen, English pioneers in geology and paleontology. The philosophy pervading these volumes was that an all-powerful deity had planned the entire range of past and present creation, making impossible any genetic connection between ancient and modern forms. Exact study, like that of the work on fossil fishes, would yield knowledge of the creative design. This view meant that Agassiz discovered many "new" species in order to prove the separate and special creation of species. Convinced his books would not be published unless he produced them himself, he established a publishing center at Neuchâtel, which employed the latest technology in photo duplication and issued the work of Agassiz and his assistants in the form of bibliographies, dictionaries, and research publications.

Between 1837 and 1843 Agassiz did remarkable work in glacial geology. In his paper "Discours pronomcé à l'overture des séances de la Société Helvétique des Sciences naturelles" (July 1837) and his book Études sur les glaciers (1840), he posited that a massive ice sheet had covered all of Europe and upon its retreat had left behind polished and scratched rocks and moraines to mark its path. The glacial period, or Ice Age, was cited as a gigantic catastrophe, brought about by the deity as still another demonstration of power and planning that made impossible the genetic relationship of animals and plants from one geological period to another. Although not original with Agassiz--a Swiss naturalist, Jean de Charpentier, had announced the glacial theory previously--Agassiz publicized it and applied glacial concepts to all of Europe.

Cécile Braun Agassiz left her husband and Neuchâtel in the spring of 1845. Never at home in the crude Swiss environment, she had become increasingly depressed and discomforted, especially by the seeming influence that Edward Desor, Agassiz's secretary, wielded over her husband. Overburdened with debt, Agassiz had to close the printing establishment, and, with the departure of former colleagues, friends, and wife, the scientific factory and productive environment was no more. When Agassiz's fortunes were at their lowest, however, fortuitous events intervened, a common experience in his life. Influenced by Humboldt, Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia announced a grant of $3,000 to Agassiz for a two-year study comparing the flora and fauna of the United States with that of Europe. Soon thereafter, John Amory Lowell, cotton manufacturer and head of the Lowell Institute, invited Agassiz to deliver a course of lectures at the institute, the exemplar of popular culture in New England.

Agassiz took America and New England by storm from his earliest days in the New World. Naturalists were eager to show him examples of fossils, and wealthy and established New Englanders were delighted by the Swiss savant with a charming accent who spoke with such ease and enthusiasm about ancient fish, powerful ice action, and the notables of European science and culture. Benjamin Silliman, Jr., a Yale chemist, said Agassiz was "full of knowledge on all subjects of science, and imparts it in the most graceful and modest manner and has, if possible, more of bonhomie than of knowledge" (Lurie [1960], p. 125). Asa Gray joined in the litany of praise: "Agassiz charms all, both popular and scientific! I observed to him that there was much quite new to me in his last lecture. . . . He replied that it would be equally new in Paris, much of it" (Lurie [1960], p. 127). Commoner and Brahmin alike were pleased to hear the reverence Agassiz accorded to God's efforts to order the "plan of creation in the animal kingdom," and his lectures of this title had to be repeated, so great was the demand for them. In less than two years of lecturing in America, he was able to repay almost $20,000 in European debts. After the death of his wife in Carlsruhe in July 1848, Agassiz arranged for his children to join him in the United States, and by 1850 the family was reunited.

Provision for both family and future was guaranteed by two events that wedded Agassiz permanently to the United States. In the fall of 1847 the Harvard University Corporation appointed him professor of zoology and geology in the newly established Lawrence Scientific School. The institution was to be based on the concept that technology and applied sciences were necessary skills in the new industrial economy then transforming the nation. Agassiz's appointment, though arranged by representatives of the new industrial elite such as Lowell and Abbott Lawrence, was discordant with these aims. It was also much desired by Harvard conservatives such as Francis Bowen, Cornelius Felton, and Charles Eliot Norton, all of whom saw in Agassiz a bulwark against radical ideas in science, such as the development theory.

In 1850 yet another tie was forged when Agassiz married Elizabeth Cabot Cary (Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz). Sixteen years his junior, "Lizzie" Cary was an uncommonly intelligent, modern young woman who made Agassiz his first real home. She was also a well-connected Bostonian, with a family background in mercantile and financial enterprises. Soon the Agassiz home on Oxford Street became the center of Cambridge intellectual life for foreigners, Bostonians, and Harvard professors. Alexander Agassiz was specially grateful for his new stepmother because he found in her a solid comfort and understanding love that soothed his recent maternal loss and encouraged his early ventures in natural science.

As a professor, Agassiz badgered Harvard authorities relentlessly, seeking money for a major museum that would stimulate the love of nature, instruct the public, and serve to train advanced students. By 1859 his efforts had wrested sums totaling about $600,000 from wealthy Bostonians and the state of Massachusetts to build a fireproof museum. The building, opened in November 1859, attracted an impressive number of students who had come to Cambridge to work under Agassiz. These postgraduate students--some of them subsidized by scholarship funds--had a unique opportunity to gain firsthand knowledge of nature unrestricted by the formalities that hindered European students. The great majority of practicing naturalists active during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries could trace their educational lineage to Agassiz and his museum.

Agassiz believed that a modern museum should also serve as a research storehouse for international exchanges and the needs of naturalists. In philosophical terms, he planned the museum to demonstrate the master plan the deity had fashioned for the natural world, thus showing the "type plan" of various classes and emphasizing the distinct and separate creation of species. With Agassiz's mania for collecting and identifying the "entire natural kingdom all at once," the museum was soon filled to overflowing with specimens. Agassiz always wanted still more; he scoured Europe for valuable collections and, in a great burst of activity, collected vast numbers of fish "species" during an exploration he and his wife made to Brazil and the Amazon in 1864-1865. Belief in special and separate creation drove his quest to find "new" species in an effort to prove the handiwork of God.

To some colleagues Agassiz and the character of his museum seemed to add little to conceptual knowledge of natural history, and he was criticized as "species mad." His once shining reputation was tarnished by a series of Boston debates over the evolution question in which he defended his position poorly in the eyes of some students and naturalists. His continued dogmatism led those unhappy with his views to refer to him as "prince of charlatans," where once they had praised the virtues of the "prince of naturalists." In the 1850s, moreover, Agassiz's adherence to special creationism led him to support the view that the different races of man were distinct species. In the hands of some defenders of slavery this meant that the white race was scientifically superior to the black because of different origins and physical characteristics. While Agassiz did not defend racial inequality, his position lent scientific credibility to the cause of southern intellectuals and further alienated Agassiz from liberal New England scientists and philanthropists.

Sensitive to the decline in his reputation, Agassiz determined to regain his former authority. He announced in 1855 the forthcoming publication of a projected ten-volume work, Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America, planned to comprise a survey of the totality of American natural history. The volumes would cost twelve dollars each, with publication to begin when 450 subscribers came forth. In total, there were more than 2,500 subscriptions, further testimony to the massive public appeal of Agassiz. Voicing his aspirations and apprehension, Agassiz told Sir Charles Lyell, "I have tried to make the most of the opportunities this continent has afforded me. Now I shall be on trial for the manner in which I have availed myself of them" (Lurie [1960], p. 196). Despite the fanfare surrounding the volumes, only four were ever published, and two were highly technical analyses of the embryology of North American turtles. The first volume (1857) comprised the notable Essay on Classification, a book that encapsulated Agassiz's views on classification, the philosophy of nature, and the sanctity of the species concept.

The work drew mixed public reviews. Published just two years before Charles Darwin's epoch-making Origin of Species (1859), Agassiz's views were repetitions of ideas he had learned long ago from Cuvier and repeated many times in books and lectures. Agassiz saw himself as the ideal modern naturalist who, by virtue of keen observations, described and analyzed empirical evidence that led to beliefs that were above and beyond experience. This was not a unique stance for naturalists of the 1850s: Gray, James Dwight Dana, and others searched for some comfortable ground allowing at once for empiricism and faith in a higher power. It was not Agassiz's science that such naturalists found essentially discomforting; rather, it was the layer of dogmatism and rectitude that encased his ideas and his unwillingness to credit diverse approaches.

In an age of doubt about older assumptions, Agassiz's views seemed moribund. Some naturalists were frustrated by this rigidity, since it seemed to them that Agassiz, with the concept of the glacial period, had provided a mechanism for change. Moreover, his emphasis on the interplay and plasticity that shaped the stages of embryology, that is, the history of individual development recapitulating the history of a species or group as well as the geological order of succession, was another intriguing mechanism for appreciating evolution. Darwin was intrigued by the idea of phylogeny recapitulating ontogeny, but Agassiz drew away from the idea of so-called "triple parallelism" because of fear it would become a useful tool for evolutionists and because he never intended the concept to confirm the evolution hypothesis. Even though Agassiz tried to understand evolution more sympathetically by making a trip around South America, retracing Darwin's voyage, this 1872 venture did not lead him to depart from his view that the evolution idea was "a scientific mistake, untrue in its facts, unscientific in its method, and mischievous in its tendency" (Lurie [1960], p. 298). Agassiz continued to view the Harvard museum as a repository of "facts" to disprove Darwin. But his many-faceted life of lecturing, administrating, and collecting left little time for careful, reflective study. Instead, much to the dismay of his American colleagues and Darwin's friends, Agassiz turned to strident anti-Darwinian attacks in the popular press, a stance that infuriated men such as Gray and Dana.

As a result, Agassiz found himself excluded from the politics of American science. He had been one of those who spearheaded the formation of the National Academy of Sciences in 1863, but perceived dictatorial methods of membership selection resulted in a stinging electoral defeat, another measure of a decline in his status. The professional sense of Agassiz as an impediment to free inquiry and publication was heightened by the complaint of his assistant on the Contributions, Henry James Clark, who claimed authorship of significant parts of the volumes on turtles. Agassiz's students also felt the anguish of alleged plagiarism and domination, and by 1863 many had left the museum on their own or at Agassiz's direction. Such a condition harked back to earlier controversies with coworkers such as Karl Vogt and Edward Desor in the field of embryology, each of whom made public the same kind of complaint. Agassiz defended his position on the grounds that works commenced under his direction or intellectual impulse were in fact his "intellectual property" and could not be taken casually by another. Although no one doubted his creativity, this position, which is not unusual in modern collaborative work, nevertheless placed Agassiz in uncomfortable situations throughout his career.

For Agassiz, there was no division between research and communication, and he lived for the ability to make his ideas known to others. He made a brief attempt to reaffirm his popular standing by organizing in the summer of 1873 the Anderson School of Natural History on Penikese Island in Massachusetts, where schoolteachers could learn to "study nature, not books," a lifelong aphorism that became attributed to him.

Agassiz remained at Harvard until his death. When he died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Americans deeply mourned his loss as if a pied piper of science had left them. The vision and image of Agassiz as a romantic, singular individual, energetically devoted solely to the study of nature remained fairly constant until recently, when more sober assessments have placed both his virtues and his faults in a more objective light.

Bibliography

The Agassiz papers are in the Houghton Library, Harvard University. Agassiz manuscripts are located at the Archives of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard. The papers of James Dwight Dana at Yale University, Asa Gray at Harvard, Alexander Dallas Bache at the Library of Congress, and James Hall at the New York State Museum, Albany, also contain useful Agassiz material. Bibliographies of Agassiz's publications are in Bibliographia zoologiae et geologiae (4 vols., 1848-1854); Jules Marcou, Life, Letters and Works of Louis Agassiz (2 vols., 1895); Agassiz, Monographies d'échinodermes vivans et fossiles . . . (4 vols., 1838-1842), Études sur les glaciers (1840), and Twelve Lectures on Comparative Embryology (1849); and Edward Lurie, ed., Essay on Classification by Louis Agassiz (1962); Geological Sketches (1866); Geological Sketches, Second Series (1876). Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, ed., Louis Agassiz: His Life and Correspondence (2 vols., 1885), is a labor of love by Agassiz's wife, with many useful letters. Lurie, Louis Agassiz: A Life in Science (1960; rev. ed., 1988), is the standard interpretation. Mary P. Winsor, Reading the Shape of Nature: Comparative Zoology at the Agassiz Museum (1991), contains useful information and analyses of Agassiz's role and concept of museum building.

Edward Lurie

Citation:

Edward Lurie. "Agassiz, Louis";

http://www.anb.org/articles/13/13-00016.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Wed Aug 07 2013 17:12:47 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)