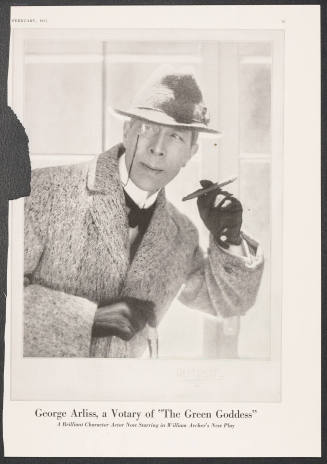

George Arliss

Arliss, George (10 Apr. 1868-5 Feb. 1946), actor, was born in London, England, the son of William Arliss-Andrews, a printer and publisher. His mother's name is unknown. He grew up in literate, cultured, and somewhat bohemian surroundings. The family home in Bloomsbury was close to the British Museum, and his father was patron of a circle of writers and eccentrics who frequented it. Privately educated, he became stagestruck at age twelve when introduced to amateur theatricals by Joseph and Henry Soutar, two sons of an acting family who also became actors.

Through the Soutars, Arliss was hired at eighteen to play walks-ons and extras at a suburban London theater, where he first appeared on the stage in 1886. Arliss learned stage craft and art in the following years through work in stock, repertory, and touring companies. After gaining better roles in road productions, he came to London's West End, playing a small role in a successful production, On and Off (1898). While still on tour, he wrote a farce, There and Back, which was performed by stock and amateur companies for years thereafter. Through the years he continued to write, without notable success. In September 1899 Arliss married actress Florence Montgomery; they had no children.

Arliss joined the company of prominent actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell, playing in productions of two of her starring vehicles, The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith and The Second Mrs. Tanqueray, in the 1900-1901 season. In 1901 he went with her company to present the plays in New York. "I was quite unprepared for what followed," he said in an interview for Windsor Magazine (Aug. 1932). After excellent notices, Arliss found himself "quite amazed when these were followed, by next post, by offers of engagements from American managers." He signed with David Belasco and appeared as the sinister Japanese official Zakkuri in The Darling of the Gods (1902) to widespread acclaim. He became a member of Minnie Maddern Fiske's outstanding company in 1904 and remained with it in New York and on tour through 1907, playing important character roles. It soon became evident that Arliss had star quality: a Chicago reviewer of his performance as a callous English aristocrat in The New York Idea wrote, "George Arliss . . . was exceptionally entertaining. His own personality is so vivid and attractive and his art so polished that his own skill and individuality carried rather an absurd part to classical distinction. He was welcomed with almost as much sincere enthusiasm as was the star" (Chicago News, 16 Oct. 1906).

Arliss arrived at stardom playing a Mephistophelean character in a comedy, The Devil (1908). Two productions of the play were presented at the same time because two producers both claimed to have rights to it. Arliss's performance was found superior by the public and carried the day. The New York Evening Journal (20 Aug. 1908) wrote, "His curious intonation, his mordant emphasis, his angular grace, went into the part a perfect fit. Never had we seen this kind of Satan--so brilliantly impertinent, so fashionably bad-mannered, so witty, so casual, and yet so deadly." His star status was confirmed permanently when he appeared in the title role of Disraeli (1911). A New York Times reviewer (19 Sept. 1911) predicted that "Mr. Arliss's highly interesting and skillfully contrived performance . . . will be chiefly responsible for the success of [the] play." It ran in New York and on tour until 1915.

Later stage successes came in the title role of Alexander Hamilton (1917), which he co-wrote, as the evil rajah in The Green Goddess (1921), and as the swaggering old shipowner in Old English (1924). His stage career ended with semisuccess in his only attempt at Shakespeare, playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (1928). Ultimately, he turned to talking pictures because he disliked the rigors of touring plays and thought playwrights of the 1920s had turned to bad or vulgar writing, which made it increasingly difficult for him to find suitable parts.

Arliss had been a stage star for twenty years because he had mastered the secret of remaining a star: giving the public a variety of roles that still showed off a consistently attractive and recognizable personality underneath. Arliss considered himself basically a character actor. His apprentice years had given him the ability to play many sorts of character roles. As a star, he specialized in three types of roles: historic figures, villains, and still-vital older gentlemen. To find plays for himself, he spent a great deal of time reading scripts, poring through hundreds. "He knows," reported Strand Magazine (Apr. 1932), "He knows with as much certainty as there is in this uncertain world whether a play is a George Arliss play. Since he was in a position to choose plays for himself, he has never chosen a failure." His starring roles always presented Arliss as a man of power, an autocrat who dominated others with the power of his mind. His forte was subtlety and finesse of movement and intonation. He could not convincingly play parts that demanded emotional abandon, a point that some critics of his Shylock noted. Arliss further remained recognizable by adapting the historical appearance of his famous men to his own distinctive face and physique.

Speaking of Arliss's character, once an interviewer wrote, "He confesses to his share of the actor's vanity--boasts of it, in fact, says that it is inherent to the profession" (Pearson's, Feb. 1910). Yet offstage Arliss shunned public attention. He was devoted to his wife, a chief adviser who also played all of his stage and screen wives. She and his longtime theater dresser, Jenner, made sure his every need was met. Arliss ate vegetarian meals, walked every day, and faithfully returned home to England for three months every summer after performing nine months in the United States. His manner was quiet, studious, and cultured. He displayed both wit and humor in conversation and in his autobiography, which was written near the end of his stage career and titled Up the Years from Bloomsbury (1927). His long, thin, bony face with its beaky nose gained added distinctiveness by his lifelong use of a monocle offstage.

Arliss had begun making silent films in 1921, mainly repeating his major stage roles and in the process learning what acting for the camera required. With the arrival of talking pictures, he went seriously into film work at age sixty. "Harry Warner told me," he recalled, "that when he decided to do Disraeli he did not expect it to pay, but he was using me as an expensive bait to hook people into the cinema who had never been there before" (New York Times, 6 Feb. 1946). Instead, the film was an international smash hit, winning Arliss an Academy Award as best actor for the 1929-1930 season.

Having appeared successfully in his historic-figure persona, Arliss went on to his villain, in The Green Goddess (1930), and his grand old man, in Old English (1930). He remade two other silent films as talkies: The Ruling Passion (1922) became The Millionaire (1931), and The Man Who Played God (1922) retained its title for the 1932 version. By now, Arliss's box office power was such that he could demand run-through rehearsals of each production before camera work started. Two Photoplay articles (May 1931 and June 1933) show that he had control over the script, the choice of director, even the costumes and the actors' diction. In effect, he was a star who was the auteur of his own films. After making three comedies and Voltaire (1933), he reached the height of his film career in The House of Rothschild (1934), where he played both Mayer and Nathan Rothschild. According to the New York Times (15 Mar. 1934), "Mr. Arliss outshines any performance he has contributed to the screen, not excepting . . . Disraeli."

Later Hollywood films did not prove as successful. Arliss wound down his motion picture years back in England. His last appearance on screen was in a storybook comedy of eighteenth-century smuggling, Dr. Syn (1937). He played a pirate who has supposedly been hanged but who reappears as the parson of an English village, helping it prosper by directing its thriving smuggling enterprises, "a sort of maritime Robin Hood," according to the New York Times (15 Nov. 1937). Nevertheless, Arliss retired when his wife lost her eyesight. In 1940 he published a further part of his autobiography, My Ten Years in the Studios. He died at his home in Maida Hill, London.

Arliss claims a place in theatrical and film history for his fifty-year career as a character actor who attained and kept star status by his ability to give brilliant performances in roles he had chosen carefully to display his abilities and obscure his limitations and by his ability to dominate any production through the power of his personality.

Bibliography

Materials on his life and career are in the Billy Rose Theatre Collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center. Besides the books mentioned earlier, Arliss wrote an introduction to On the Stage (1928). Quotations of Arliss's own views on the stage and himself, along with theatrical criticisms of his work, are in William C. Young, Famous Actors and Actresses of the American Stage (2 vols., 1975). Articles about Arliss include W. P. Dodge, "The Actor in the Street," Theatre, Dec. 1909; B. N. Wilson, "The Autocrat of the Stage," Theatre, Oct. 1925; Harry Lang, "His Two Bosses," Photoplay, May 1931; John Gliddon, "The Art of George Arliss," Strand Magazine, Apr. 1932; W. S. Meadmore, "George Arliss Speaks," Windsor Magazine, Aug. 1932; Ruth Biery, "Arliss Puts His Foot Down," Photoplay, June 1933; and Ken Hanke, "George Arliss Reappraised," Films in Review, Nov. 1985. All articles include portraits and production stills. An obituary is in the New York Times, 6 Feb. 1946.

William Stephenson

Citation:

William Stephenson. "Arliss, George";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00034.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:20:47 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.