Ethel Barrymore

Barrymore, Ethel (16 Aug. 1879-18 June 1959), actress, was born Ethel May Barrymore in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Maurice Barrymore, an actor, and Georgiana Drew (Georgie Drew Barrymore), an actress. The second of three children (her brothers Lionel Barrymore and John Barrymore also distinguished themselves on stage and screen), Ethel was born into a family whose theatrical roots reached back four generations. Her mother, a spirited and popular comedienne, had married Maurice Barrymore (born Herbert Blyth in India), a handsome and fast-living matinee idol who had come to the United States from England in 1874. But Ethel would know neither parent well. Her grandmother, Louisa Lane Drew, one of the nineteenth century's leading comediennes and theater managers, was the family matriarch and a dominant figure in her granddaughter's life, particularly as her parents frequently were on tour.

Although born into a strongly Episcopalian family, Georgiana's conversion to Roman Catholicism led her to have Ethel baptized a Catholic, and at age six she was sent to live in a convent school in Philadelphia. At thirteen Ethel accompanied her mother to California where Georgiana was to convalesce from a bout with tuberculosis. Her mother's death soon thereafter thrust adult responsibilities on Ethel, and for the rest of her life she assumed a maternal role toward her brothers. Family fortune changed in another way. Returning to the convent school in autumn 1892, Ethel was informed a few months later that her grandmother had given up management of the Arch Street Theatre and that she must leave school and begin acting. "Suddenly there was no money, no Arch Street Theatre, no house, and I must earn my living," she recalled in her autobiography. She sacrificed her early dreams of a career as concert pianist to immediate necessities.

Although her acting experience was limited to childhood theatricals with her brothers, Barrymore joined her grandmother's Canadian tour of Sheridan's The Rivals. She soon learned the rigors of the road, experiencing even the humiliation of sneaking out of a hotel with the company for want of money. Nor did the Barrymore name always exempt her from the drudgery of making the rounds at theatrical agencies. Yet family ties did prove valuable. Her uncle John Drew, Jr., then a reigning star of drawing room comedies, prevailed on producer Charles Frohman to give her apprentice roles. She successfully understudied Elsie de Wolfe's Kate Fennel in The Bauble Shop (1894), which led Frohman to give her the part in a touring company. As a coquettish maid in John Drew's Rosemary (1895), she displayed the charm that would propel her to stardom.

An invitation from William Gillette to appear in his London production of Secret Service (1897) proved to be a decisive moment in Barrymore's career. Not only did London audiences take to her, but English society threw open its doors to this American cousin. With her wide interests and unaffected yet sophisticated manner, she charmed England's social and artistic elites. A series of English suitors (including Winston Churchill) sought her hand through the years. One of these was Laurence Irving, whose celebrated father, Henry Irving, offered her roles in The Bells (1897) and Peter the Great (1898).

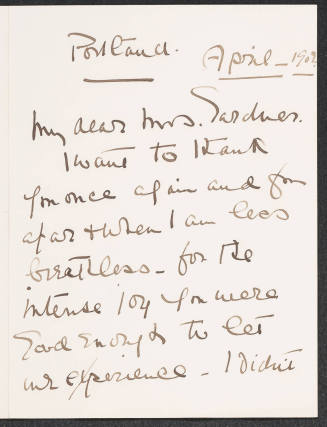

Barrymore returned to the United States in 1898 to discover that her English reception had made her an American celebrity. Frohman, America's leading theatrical producer, added her to his stable of stars. In 1900 he cast her as Madame Trentoni in Clyde Fitch's social comedy Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines. Its Broadway debut the next year was a sensation, thrusting Barrymore into stardom and making her a fashion trendsetter for young American women. She continued under Frohman's management until his death in 1915, playing with her "rare and radiant girlhood" the eternal ingenue in second-rate plays such as Cousine Kate (1903), Alice-Sit-by-the-Fire (1905), Her Sister (1907), and Lady Frederick (1908).

Although Barrymore enjoyed the adulation of stardom and the easy entrée into high society, she grew restless playing juveniles. Her attempt at Nora in A Doll's House (1905) failed. It remained for marriage, motherhood, and the vehicle of Arthur Wing Pinero's Mid-Channel (1910) to elevate her to more mature dramatic roles. This part was followed by other successes in The Shadow (1915), Edna Ferber's Our Mrs. McChesney (1915), and, most notably, Zoë Akins's Déclassée (1919), which enjoyed long runs in New York and on tour.

The early 1920s, however, also saw the dissolution of her marriage, which had taken place in 1909, to socialite Russell Griswold Colt. The union had produced three children, who remained with their mother. The first half of the decade also brought some stage failures, particularly the harsh reception given to her attempt at Shakespeare's Juliet in 1922 (although she was better received a few years later as Ophelia and Portia). Winning critical acclaim in The Second Mrs. Tanqueray (1924), two years later she found her best vehicle of the 1920s, Somerset Maugham's comedy The Constant Wife, in which she enjoyed three years' success. At the end of the play's run Lee Shubert and J. J. Shubert lured her to their management with the construction of the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, which she inaugurated in 1928 with the opening of The Kingdom of God.

The depression ushered in the most difficult period in Barrymore's career. Scarlet Sister Mary (1930) failed disastrously, and no other suitable roles came along in following years. Compounding her professional difficulties was acute financial distress (including an ongoing battle with the IRS over unpaid taxes) and a drinking problem, which made her a risk to put on stage.

To survive the thirties she reverted to two familiar strategies of the past. One was to return to the vaudeville stage, which she had done intermittently since 1912 in the one-act play The Twelve-Pound Look (1933). The other was to venture again to Hollywood. Although she had made several silent films beginning in 1914, she had publicly let her scorn of Hollywood be known. But financial need and the chance to act with both brothers (for the only time) led her to accept MGM's offer to make Rasputin and the Empress in 1932. Radio also came to her financial rescue, as she did a series of her old stage roles for NBC in 1936.

After appearing in a series of weak vehicles during the late 1930s, Barrymore's career took an abrupt turn for the better in 1940 in Emlyn Williams's The Corn Is Green. Her portrayal of Miss Moffat, a Welsh schoolteacher, became perhaps her most acclaimed role. The play ran in New York and on the road for three years, interrupted in 1944 to allow her to make the film None But the Lonely Heart (for which she received the Academy Award as best supporting actress).

The 1940s would become Ethel Barrymore's decade. Having salvaged a career that apparently was over in the early 1930s, she won new critical and public acclaim and an adulation known to few other American actresses, being once again touted as "first lady of the theater." But Barrymore would appear in only one further theatrical production of note, Embezzled Heaven (1944). A serious bout of pneumonia and various film offers led her to permanently move to southern California. She acted in twenty films (always in prominent supporting roles) from 1946 through 1957, most notably The Spiral Staircase (1946), for which she received another Academy Award nomination, and Night Song (1947). Two more Oscar nominations as best supporting actress followed for The Paradine Case (1947) and Pinky (1949). In the early 1950s she did some radio work and made several television appearances, even briefly hosting her own series, "The Ethel Barrymore Theater." She died in Los Angeles.

Barrymore epitomized stylish elegance. "Of all the people I have known," said the author Eliot Janeway, "Ethel was the most urbane, the most civilized, the most interested, the most articulate." These qualities also defined her stage presence. Her acting attained depth in the 1920s and a technical mastery that enabled her to maintain superb performances, even after long runs. She also had a much-admired (and imitated) voice and an imperious bearing that commanded respect, and her beauty remained scarcely diminished to the end of her life. By birth and manner, she represented the grand tradition of American theater, whose passing coincided with her career.

Bibliography

The major archival material on Ethel Barrymore resides in the Robinson Locke Scrapbooks at the Billy Rose Theatre Collection of the New York Public Library/Lincoln Center. Barrymore's autobiography, Memories (1955), lacks serious reflection on her life. The most astute biography (a collective biography of Ethel, Lionel, and John) is Margot Peters, The House of Barrymore (1990). Hollis Alpert, The Barrymores (1964), is likewise a collective portrait. Good short sketches are found in Notable American Women (1980) and Notable Women in the American Theatre (1989). An obituary appears in the New York Times, 19 June 1959.

Benjamin McArthur

Citation:

Benjamin McArthur. "Barrymore, Ethel";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00063.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:25:32 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.