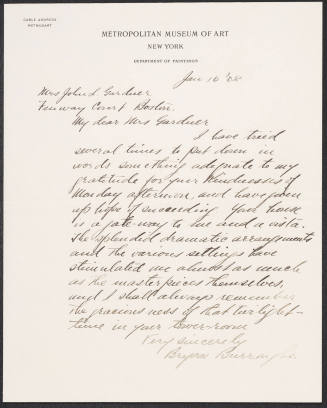

Bryson Burroughs

Painter; curator of paintings at MET

Burroughs, Bryson

Date born: 1869

Place born: Hyde Park (Boston area), MA

Date died: 1934

Place died: New York, NY

Painter and Curator of Paintings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1909-34. Burroughs was the son of Major George Burroughs and Caroline Bryson (Burroughs). His family moved to Cincinnati after his father's death. He studied at the Art Students League, NY, between1889-1891, leaving for Paris that year to study at the Academie Julian under Puvis de Chavannes. He married Edith Woodman (1871-1916) in England in 1893. He spent the year 1894 in Florence, returning to the United States in 1895. In 1906 the curator of painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Roger Fry (q.v.) appointed Burroughs his assistant. In 1907 Burroughs and Fry persuaded Edward Robinson (q.v.), the Assistant Director, to acquire at auction Renoir's Madame Charpentier and Her Children for $20,000. The price seemed so inflated that the Metropolitan trustees nearly fired Fry and Burroughs. When Fry resigned later the same year, Burroughs was made acting curator and then Associate in 1909. He was responsible for updating the paintings catalog for the museum. After his first wife's death, he married Louise Guerber (later a curator at the Metropolitan) in 1928. During the 1930s when the Metropolitan and the Museum of Modern Art, NY, had an informal arrangement to work together, Burroughs provided the text for an exhibition catalog for MoMA on Winslow Homer and other American artists. Although he was responsible for purchase of many European paintings for the museum (Brueghel's Harvesters and a Michelangelo drawing of the Lybian Sybil), he is most noted for adding American artists to the Metropolitan's collection. He died of tuberculosis at his home at age 65. His son, Alan Burroughs (1897-1964), was a lecturer in art at Harvard University and a research fellow at the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard; Burrough's daughter, Betty, married the painter Reginald Marsh.

Burroughs wrote enthusiastically about the modern French artists Cézanne and the Impressionists, yet his personal painting style was ironically the pallid academic genre of Puvis de Chevannes, his teacher in Paris.

Home Country: United States

Sources: Tomkins, Calvin. Merchants and Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2nd. ed. New York: Henry Holt, 1989, pp.107, 168; Saur Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon 15: 276-77; The Paintings of Bryson Burroughs (1869-1934): February 18-March 17, 1984. New York: Hirschl & Adler Galleries, 1984; Owens, Gwendolyn. "Pioneers in American Museums: Bryson Burroughs." Museum News 58 (May-June 1979): 51; [obituary:] "Bryson Burroughs Dies." New York Times November 17, 1934, p. 15.

Bibliography: and Mather, Frank Jewett, Jr., and Goodrich, Lloyd. Winslow Homer, Albert P. Ryder, Thomas Eakins. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1935; Catalogue of Paintings [of the Metropolitan Museum of Art]. 7-9th eds. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1924-1931; Catalogue of an Exhibition of Spanish Paintings from El Greco to Goya. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1928.

https://dictionaryofarthistorians.org/burroughsb.htm

BORN in 1869, Bryson Burroughs lived 65 years, working for the last 28 of them at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There, he began as assistant to Roger Fry and, when the British scholar and critic left in 1909, assumed his position as curator of paintings, doing much to further the museum's collection. Calvin Tomkins, in his ''Merchants and Princes,'' reports that Burroughs's coups included the first Cezanne to enter a public collection, ''La Colline des Pauvres,'' Bruegel's ''Harvesters'' and Van Eyck's ''Crucifixion and Last Judgment.'' The curator didn't neglect native talent either, organizing shows by Albert Pinkham Ryder and Thomas Eakins, as well as buying their works.

Throughout his career at the Met, Burroughs remained the painter he had trained to be in Cincinnati, where he grew up, and at the Art Students League and at academies in Paris, where he encountered Puvis de Chavannes. The French master affected many artists, from Gauguin to Maillol, but evidently none so much as Burroughs, whose paintings and drawings are now at Hirschl & Adler, 21 East 70th Street.

But despite his enlightened approach to the art of his own time, the American was far less of a modernist than Puvis. He adopted the French master's flatness and his faded palette, but apparently was most interested in keeping the great subjects of art alive - biblical stories, Greek myths and the like. Generally, this impulse is born of a deep intimacy with art history coupled with the na"ivete that is very much the byproduct of an academic life. It's odd enough that anyone, let alone a museum curator, should have painted, in 1912, Judith bearing the knife that did Holofernes in, the blood on it matching the fires in the enemy's camp in back of her. That a gallery should exhume the canvas in all seriousness, along with about 60 other paintings and drawings, seems very odd indeed. The show was selected by Douglas Dreishpoon from the Burroughs cache, which was found only last year in the loft of a Rhode Island barn.

On the other hand, there have been stranger revivals. Undoubtedly, many of the pictures are funny: Proserpine, back from the underworld, advances on her mother, Demeter, for all the world like a garden-party hostess uttering, ''Dahling!'' In another work, a plump and milky Venus hangs on the neck of a skinny Adonis, who is obviously more interested in the hound sharing their idyll, and when the goddess stars with Mars, she looks like a Reginald Marsh lovely, Mars like a Bellows pugilist. But there seems no doubt either that the humor is intentional and that Burroughs, however much he loved art, loved nature as much. In a 1931 scene of the banishment from Eden, Eve spins and Adam levers a rock, both of them burly enough for a Works Progress Administration mural. Still, the real interest is in two enchanting rabbits in the foreground being tended by Cain and Abel masquerading as Christopher Robin- type tots. Burroughs's Prodigal Son gets as big a welcome from a black- and-white dog as from his parents. It's all quite beautifully painted.

The artist was, by all accounts, an amiable man, who cherished family and friends, and the outdoor life just as much as he did art. So it's not improbable that Burroughs, knowing that he could never contribute to high art, painted these affectionate fantasies as a respite from being art's servant. (Through March 17.)

Also of interest this week: John Chamberlain (Fourcade, 36 East 75th Street): That this show overlapped briefly with the Willem de Kooning retrospective at the Whitney Museum is unfortunate. The coincidence is a reminder of John Chamberlain's debt to Abstract Expressionism, notwithstanding his alter ego as a crusher of automobile bodies and therefore a theoretical rebel. Actually, Chamberlain's neo-Dadaism predates pop, but the contradiction has earned him critical lumps. So has his pursuit of the same idea with few deviations for more than 30 years.

These are matters artists can usually get away with flouting if they either have luck or some intellectual compensation to offer. Chamberlain has not really had either, and though changes have occurred in his work, they haven't been conclusive. For instance, he is not the automatist he was, to the extent that he will use sheet metal as well as crushed autos and will apply his colors before, during and after the sculptural process. However, the artifice stops there, and the color, in its variousness and the seeming randomness of its application, positively fights the compositions, most of which are large and free-standing. Were the material not obviously metal dented, folded and rolled, the sculptures could be bolts of cloth stacked in picturesque disarray in a dry-goods store.

That this doesn't have to be the case is proved by ''Charcoal Fudge,'' a piece measuring 9 feet across that comprises a large squarish mass in black, of which one end extends into a beam shape, also black, while the other end sandwiches a few vertical folds of white before coming to rest against a slimmer, rounded form in red and yellow. It is the boldest image in the show. (Through March 31.)

Michael Hurson (Clocktower, 108 Leonard Street): In this show of drawings, Michael Hurson shares the spotlight with Henry Geldzahler making his debut as guest curator at the Institute of Art and Urban Resources. The display consists of about 60 works in charcoal, pastel, crayon, gouache and combinations thereof from 1969 to 1983. The Ohio-born Mr. Hurson has made a considerable advance on his early pictures of eyeglasses converted into little personages and of pool furniture and motel interiors.

Since then, he has turned his attention to human subjects, abstracting faces and bodies into a personal geometry not untouched by Cubism. It is, though, a Cubism closer to that practiced in the 1930's by Paris expatriates than to anything by Picasso or Braque. Mr. Hurson, furthermore, likes to exaggerate eyes in a manner recalling Alfred Maurer, and he also indulges in such comic-strip tricks as blobby noses and quaint stances. But in recent years he has come up with some quite startling images, notably the 1982 ''Fire Hydrant,'' which emerges from a layer of black-and- gray gouache superimposed on similarly ''woven'' layers of chalk.

Simpler, but no less striking images are a 1981 approximation of a Doric column defined mainly by its black-ink background and a recent work involving a white rectangle enclosed by a white frame, which is, in turn, rimmed by a frame drawn in black and brown, the whole contained in another real white frame and glazed. This moderately entertaining show is bound for the Art Institute of Chicago. (Through March 25.)

Stephen Ludlum and Peter Young (Oil and Steel, 157 Chambers Street): For his first New York solo, Stephen Ludlum shows eight canvases, most of them large and all exceedingly cryptic. The artist has two styles, both typified by one work in three parts. In the first is a portion of a huge clenched fist inscribed in white lines on black. In the second, the lower part of a pair of legs, black on white, stands on a pedestal from which flamelike shapes emanate. A third panel features the back view of what looks like a fireman gesturing at a smoking volcano, with the figures' form modeled in the same red that defines the sky, everything else being black. Mr. Ludlum has ability but strains too hard after obscurity.

Mr. Young has been showing for more than 10 years. As of now, he is a painter who covers tall canvases with a basket weave of lines in many colors, filling the interstices with still more colors. Also eight in number, the works look from afar like big slabs of petit point, tending either to green or red in their overall hue. Scrutinized more closely, they yield implications of architectural facades and ornament. Compulsive but impressive. (Through March 10.)

Daria Dorosh (A.I.R., 63 Crosby Street): Dariah Dorosh is a painter bent on questioning the relationship between a work of art, its viewer and the so-called real space in which both are ''confronted.'' She does so by hanging most of her vividly colored abstractions, which allude to Cubism and, seemingly, to Hans Hofmann, in conjunction with objects made by four architects. One of these is Harriet Balaran, who contributes a stubby but graceful Recamier sofa in black wood, mounted on bowling balls; another is Elizabeth Diller, represented by a mirror with part of its amalgam backing scraped away; the third is Mary Pepchinski, who designed a desk made by Matthew Wolff, a carpenter, and the fourth is Donna Robertson, author of a well- made wood fence painted dark green and flanked by stiles.

The canvases are attractive, so are the objects, and they complement one another nicely. The confrontation doesn't differ greatly from that on the furniture floors of better department stores. (Through March 10.)

http://www.nytimes.com/1984/03/02/arts/art-bryson-burroughs-work-inspired-by-myth.html?pagewanted=all