Arthur Hugh Clough

Clough, Arthur Hugh (1819–1861), poet, was born on 1 January 1819 at 5 Rodney Street, Liverpool, the second son of James Butler Clough (1784–1844), a Liverpool cotton merchant of Welsh extraction, and Anne Perfect (d. 1860), the daughter of a Yorkshire banker. In December 1822 the Cloughs, with their four children, emigrated to Charleston, South Carolina. The family continued to reside in America until 1836, but Arthur was taken back to England in 1828 and for a year attended a school in Chester. In 1829, with his elder brother Charles, he entered Rugby School; there he formed a great admiration for the headmaster, Thomas Arnold, who welcomed him into his family circle where he formed lifelong friendships with the two eldest boys, Matthew and Thomas. He was taught by Arnold to take life with great seriousness and imbued with a sensitivity of conscience which in later life he came to regard as excessive. During his time at Rugby he lived up to Arnold's ideals, working hard in class and winning many prizes, editing a school magazine, and taking a significant part in school government, and in spite of a frail constitution achieving renown in football, swimming, and running.

University life: religion and politics

In November 1836 Clough won a scholarship to Balliol and went into residence in October 1837. Balliol was now beginning to compete with Oriel as the centre of academic distinction in Oxford, and Clough had as fellow students Arthur Stanley, Benjamin Brodie, Benjamin Jowett, John Duke Coleridge, and Frederick Temple. Among his tutors were A. C. Tait and W. G. Ward; the latter became a very close and possessive friend during his undergraduate days. Partly through Ward, Clough was attracted by the Oxford Movement and fell for a while under the influence of John Henry Newman. He had been brought up in an evangelical tradition by his mother, and had imbibed liberal Christianity at Rugby, and it was the devotional and ascetic rather than the dogmatic and sacerdotalist aspects of Tractarianism that attracted him. His diaries at this time show the great strain caused by enduring the pull of conflicting theological traditions, and by bearing with patience the intellectual and emotional demands of Ward. Though he kept up an increasingly lively social life, and was active in student societies such as the Union and the Decade, Clough's academic work suffered; he postponed his final examinations, and when he sat them in 1841 he obtained only a second class. He walked to Rugby to tell Arnold that he had failed.

While a schoolboy Clough had written copious but indifferent verses, publishing many of them in the Rugby Magazine over the alias T. Y. C. (Tom Yankee Clough). He began to write again with greater maturity in his second year at Balliol, and submitted competent poems in two successive years as entries for the university's English verse prize. During his undergraduate years he also wrote a number of shorter verses in a variety of metrical forms. They display the influence of Wordsworth, particularly a sequence entitled ‘Blank Misgivings of a Mind Moving in Worlds not Realised’ which follows the theme and imitates the diction of the immortality ode. Most of these early verses are of biographical rather than poetic interest.

In November 1841 Clough sat the examination for a Balliol fellowship, but was again disappointed. However, two things brought him comfort during the academic year: Matthew Arnold was now a scholar at Balliol, and his father, Thomas Arnold, was lecturing in Oxford as regius professor of history. In March he sat examinations again, this time for the great prize of an Oriel fellowship; and this time he was successful, being elected on 1 April 1842. His happiness during the succeeding months came to an abrupt end when, in June, Arnold was struck down by a heart attack. Clough tried to console himself by a month of solitary walking in Wales. By Easter term 1843 his spirits had recovered somewhat, and his diary records him enjoying, with the two Arnold brothers, the Oxfordshire excursions later described so engagingly in Matthew's ‘Scholar-Gipsy’.

At Oriel, Clough found himself a colleague of Newman, but by this time he had ceased to feel any attraction to the Tractarian movement, which had now reached a point of crisis. In 1841 Newman had published Tract XC, which claimed that it was possible to subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England (as Oxford undergraduates and MAs were obliged to do) without rejecting anything of Catholic belief. Hebdomadal council condemned the tract, and at the behest of the bishop of Oxford, Newman brought the series of tracts to an end. Ward, at Balliol, wrote pamphlets in defence of the tracts and as a result had to resign his tutorship. Clough had his own problems with the Thirty-Nine Articles: if he was to proceed to his MA he would have to subscribe to them once again, and by 1843 he had begun to feel that subscription was a crippling bondage. In 1844 he did sign, stifling his doubts, but they were not suppressed for long. He may have been encouraged to subscribe by the need to support his family: his brother George had died in November 1843 and his father in October 1844.

Meanwhile Ward, having written a Romanizing book that gave great scandal, was degraded by the university in 1845, and resigned his Balliol fellowship in order to marry. He and his new wife became Roman Catholics in June, and Newman followed shortly afterwards. Many liberals in Oxford found Newman's departure a liberation; but Clough, partly under the influence of Carlyle and German biblical scholarship, had now moved so far from orthodoxy as to find the Anglicanism even of post-Tractarian Oxford burdensome. He began to seek alternatives to his Oriel tutorship, even though Matthew Arnold had joined him as a fellow in spring 1845. During his years as a tutor he was a conscientious teacher, and in the summer vacations he took reading parties of his pupils to Braemar and Loch Ness in Scotland.

In the years following 1845 Clough's attention turned to political matters. He wrote a number of letters in 1846 on political economy, which were published in a journal called The Balance. In the same year he made his first continental tour, visiting Germany, Switzerland, and the Italian Lakes. In 1847 he wrote a pamphlet on the Oxford Retrenchment Association urging, in spite of laissez-faire economists, that conspicuous consumption in England, and especially in Oxford, should be curtailed in order to help the Irish poor during the famine. By the end of his time at Oriel he had acquired a reputation as a political radical.

Clough's religious doubts, especially about the historicity of the gospels, persisted and increased, despite the patient but uncomprehending remonstrances of Provost Hawkins of Oriel. To the disturbing influence of Carlyle was added that of Emerson, whom he first met in November 1847. At the beginning of 1848, while his fellowship still had eighteen months to run, he resigned his tutorship, telling Hawkins that he could no longer adhere to the Thirty-Nine Articles.

1848 was a year of revolution throughout Europe. ‘Citoyen Clough’ spent the spring in Paris, witnessing the French revolution at first hand. Emerson was there too, and they saw each other daily during May and June. When Emerson left Liverpool for America in July, Clough saw him off. He lamented his departure: Carlyle, he complained, had led everyone out into the desert and left them there. Emerson, in reply, laid his hand on Clough's head, and told him he was to be bishop of all England.

The Bothie

Clough's next act, however, took both his Anglican and his Emersonian friends by surprise. He spent the summer writing, not a religious or socialist tract, but a narrative poem 1700 verses long, entitled The Bothie of Toper-na-Fuosich (changed in later editions to The Bothie of Tober-na-Vuolich). The poem was published in November: in the previous month Clough had finally resigned his fellowship at Oriel.

The poem is set in the context of a Scottish reading party, in which the tutor and his pupils bear a strong resemblance to Clough and his young friends. The characters are skilfully differentiated, and the holiday exuberance of youth is vividly portrayed; the poem is rich in colourful descriptions of natural scenery. The student hero is a radical poet, Philip Hewson, who combines a belief in the dignity of labour with a keen susceptibility to feminine beauty. After two abortive flirtations, he falls in love with a crofter's daughter, Elspie, and emigrates with her to New Zealand, whither, in reality, young Tom Arnold had emigrated in the previous December. The poem contains some pointed criticism of the relationship between the sexes and the classes in Victorian Britain, but it is at the same time a nostalgic farewell to the life of an Oxford tutor.

The Bothie is written in hexameter verses, in an imitation of the metre of Homer, but with the feet measured by stress, in accordance with the conventions of English verse, instead of by length, as in Greek. In most positions in a verse of this kind, the poet is free to place either one or two syllables between each stressed syllable, and this allows the kind of flexibility that Gerard Manley Hopkins later claimed for his newly invented sprung rhythm. Clough exploited the possibilities by writing in a variety of registers, ranging from colloquial and slangy dialogue, through lyrical natural description, to abstract political and philosophical theorizing. He imitated Homer not only in metre but also in features of style: the use of identifying epithets and stylized repetition, for instance, and the positioning of powerful, self-standing, similes at key points in the narrative.

Though some critics judged the narrative too inbred an Oxford production, and others found the hexameters too rough and irregular, most reviewers acclaimed The Bothie from the outset. The poem sold well and quickly established its author's reputation as a poet. Hard on its heels followed a second publication: in January there appeared Ambarvalia, a collection of verse by Clough and his Cambridge friend Thomas Burbidge.

This collection contained Clough's choice of the poems written during the years at Balliol and Oriel. Most are short poems, recalling the trials of student years and the journeys of the religious doubter. ‘Qui laborat, orat’, admired by Tennyson, expresses the tension of prayer to a God who is ineffable; ‘The New Sinai’ dramatizes the conflict between religion and science. There are poems of love and friendship in various moods and metres, and there is a surprisingly frank celebration of fleeting sexual impulse in ‘Natura Naturans’.

Italian influences

From April to August Clough was in Rome where, since the expulsion of Pius IX in 1848, Mazzini had presided over a short-lived Roman republic. Clough's letters give a vivid account of Garibaldi's defence of the city against the besieging French army under General Oudinot. With astonishing speed he exploited this experience in poetical form, writing an epistolary novel in five cantos, Amours de voyage. This poem, which is the most enduringly popular of his works, tells the story of Claude, a supercilious Oxford graduate who is initially contemptuous of Rome, and of a young English woman he meets on the grand tour, Mary Trevellyn. By the end of the story Claude has fallen in love both with Mary and with the Roman republic, only to lose them both, as the Trevellyns travel north without him and the French restore the rule of the pope. The first draft was finished shortly after his return to England, but the final version was not published until 1858 when it appeared in an American journal, the Atlantic Monthly.

Like The Bothie, the greater part of Amours de voyage is written in hexameters; Clough is now more at home with the metre, and there are fewer of those rugged lines which bring the reader up short, uncertain where to place a stress. Each canto is preceded and followed by a short poem in an English approximation to an elegiac distich. The characterization is not as vivid as in The Bothie, but there is a dramatic energy in the narration of episodes in the siege of Rome. The personality of the anti-hero, and the downbeat ending of the poem, puzzled some contemporary readers (including Emerson) but gave it an unusual appeal to twentieth-century taste.

In summer 1848 Clough visited Naples. While there he wrote the most successful of his poems on religious topics, ‘Easter Day’. It is an unblinking denial of the resurrection of Jesus, the central Christian doctrine, in words taken from the Christian scriptures themselves; it accompanies the denial with an unflinching vision of the hopes that are given up by one who abandons Christianity. Believers and unbelievers alike have admired its emotional and intellectual power.

In October of the same year Clough became the head of University Hall, London, a non-sectarian collegiate institution for students attending lectures at University College. He was not happy there, finding it no easier to accommodate himself to the principles of the Unitarians and Presbyterians who governed it than to the articles of the Church of England which had troubled him at Oriel. His principal consolation at this period was the friendship of Carlyle. From 1850 he held simultaneously a professorship of English language and literature at University College, and wrote a number of lectures on poets and poetical topics which have survived and were published posthumously.

The most productive period of these years was a visit to Venice in 1850 in which he started a dramatic poem, Dipsychus. This is a Faust-like dialogue between a tormented youth, in two minds (Dipsychus) about his future career, and a spirit (named in one version Mephistopheles) who represents the temptations of the world, the flesh, and the devil. The scenes of the dialogue are set, often not very convincingly, in different locations in Venice; the text was often revised but never completed, and there has been little agreement among posthumous editors about the best way of presenting its fragments. None the less, in its unfinished and uneven state it contains the most impressive embodiment of Clough's mature thought on religious topics. The dialogue is conducted in many different metres, from solemn quasi-Shakespearian blank verse to Gilbertian patter-songs.

Family life and later work

At the end of 1851 Clough left University Hall. He applied in vain for a professorship of classics in Sydney. It had become important for him to find alternative employment, because he was now in love with Blanche Mary Shore Smith (1828–1904) of Combe Hall, Surrey, a cousin of Florence Nightingale, to whom he became engaged in 1852. In October 1852 he sailed with W. M. Thackeray to America, where he spent nine months in a vain search for a suitable job. He was warmly welcomed by Emerson, Longfellow, Charles Eliot Norton, and other members of the Boston literary society that he described vividly in letters to his fiancée and to Carlyle. He undertook some private tutoring and worked on a revision of Dryden's translation of Plutarch, but had no success in finding a permanent job.

Meanwhile, however, Clough's friends in England found him a post as examiner in the education office, which enabled him to marry Blanche on 13 June 1854. She was a devoted wife, and bore him at least four children, including Blanche Athena Clough (1861–1960), college principal and educational administrator, but she never fully entered into his aesthetic and intellectual concerns. In 1860 Clough's mother died; he remained close to his sister Anne Jemima Clough (1820–1892), later to become the first principal of Newnham College, Cambridge. What time he had to spare from his exertions in the education office was now spent in assisting Florence Nightingale in her campaign to reform military hospitals. It was he who had escorted her to Calais in 1854 on her first voyage to the Crimea.

By 1861 Clough's health had broken down, and he was given sick leave for a foreign tour. He went to Greece and Constantinople, and began to write his last long poetical venture, a series of tales entitled Mari magno. In this work a young Englishman, a returning American, a lawyer, and a clergyman entertain each other on an Atlantic crossing by telling stories that illustrate different conceptions of marriage and the relationship between the sexes. The seven tales of this suite, though they contain a few skilful and moving passages, in both content and expression fall far short of the standard set by the hexameter poems of 1848–9.

After a few weeks at home in June 1861 Clough went abroad again, and spent some time in the Pyrenees with the Tennysons. The attempt to recover his health was vain, and he died on 13 November in Florence, where he was buried in the protestant cemetery. His death was mourned by Matthew Arnold in his elegy Thyrsis which, like ‘The Scholar-Gipsy’, recreates the Oxford companionship of the two poets.

Afterlife

Besides Dipsychus and Mari magno many of Clough's best shorter poems remained unpublished at his death. Among them are a number of biblical lays based on the book of Genesis, a Browning-like monologue on Louis XV (‘Sa majesté très Chrétienne’), and the two poems most often anthologized, ‘Say not the struggle naught availeth’ and ‘The Latest Decalogue’.

An edition of Clough's poems was published by his wife in 1862, with a memoir by F. T. Palgrave in England, and one by C. E. Norton in Boston. In 1865 a volume of Letters and Remains contained the first printing of Dipsychus and of ‘Easter Day’. A new collection, Poems and Prose Remains, appeared in 1869 with a memoir by his wife.

Critical response to these posthumous publications was mainly very favourable. From the 1860s it was not uncommon to regard Clough as an equal partner of a poetic fraternity whose other members were Tennyson, Browning, and Arnold. A reaction against his poetry, however, set in during the 1890s, with Swinburne and Saintsbury. In the first half of the twentieth century Lytton Strachey sniggered at Clough's association with Florence Nightingale, and Leavis exalted the talents of Hopkins above all four of the original Victorian quartet.

In 1941 Winston Churchill, anxious to secure American co-operation in the fight with Hitler, broadcast some lines from ‘Say not the struggle naught availeth’ which ended ‘Westward, look, the land is bright’. This brought some at least of Clough's poetry back to the national consciousness, and in the post-war years several critics were willing to hail him as the most modern of Victorian poets. The first modern edition of the poems appeared in 1951, and a fuller, critical edition, in 1974. The 1960s and 1970s saw a series of biographies and literary studies appear on both sides of the Atlantic. Changing fashions in English departments in universities have led, since 1980, to comparative neglect of Clough's œuvre, though popular editions of the principal poems have continued to appear regularly. The start of the twenty-first century has seen welcome signs of a renewed interest in this most intelligent of Victorian poets.

Anthony Kenny

Sources

The poems of Arthur Hugh Clough, ed. F. C. Mulhauser, 2 vols. (1974) · Correspondence of Arthur Hugh Clough, ed. F. L. Mulhauser, 2 vols. (1957) · The Oxford diaries of Arthur Hugh Clough, ed. A. Kenny (1990) · R. K. Biswas, Arthur Hugh Clough: towards a reconstruction (1972) · C. Ricks, ed., The new Oxford book of Victorian verse (1987) · M. Thorpe, ed., Clough: the critical heritage (1972) · R. M. Gollin, W. E. Houghton, and M. Timko, Arthur Hugh Clough: a descriptive catalogue (1966) · Selected prose works of Arthur Hugh Clough, ed. B. B. Trawick (1966) · Burke, Gen. GB

Archives

Balliol Oxf., journals and papers · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. and drafts of poems · LUL, letters · UCL, letters :: BL, corresp. with Florence Nightingale, Add. MS 45795 · Harvard U., Norton MSS · LMA, papers as secretary of Nightingale Fund council · Oriel College, Oxford, letters to Dr Hawkins · Wellcome L., memo of conversations with Florence Nightingale

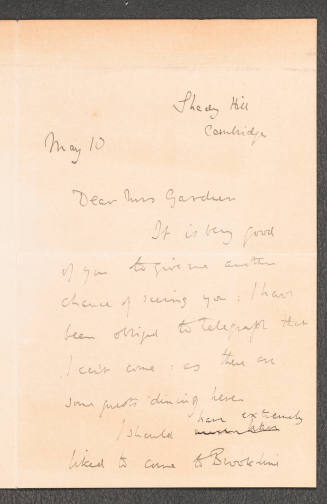

Likenesses

S. Rowse, chalk drawing, 1860, NPG [see illus.] · T. Woolner, marble bust, 1863, Rugby School · S. Laurence, portrait (after S. Rowse, 1860), Oriel College, Oxford; copy of drawing, Oriel College, Oxford · Richmond, portrait, Oriel College, Oxford · F. W. de Weldon, bust (after early etching), Charleston city hall, South Carolina · death mask, Balliol Oxf. · drawing, NMG Wales · plaster bust (after marble bust by T. Woolner, 1863), NPG

Wealth at death

£4000: probate, 18 Feb 1862, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Anthony Kenny, ‘Clough, Arthur Hugh (1819–1861)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2007 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/5711, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Arthur Hugh Clough (1819–1861): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5711