Walter Damrosch

Damrosch, Walter Johannes (30 Jan. 1862-22 Dec. 1950), conductor and composer, was born in Breslau, Prussia (now Wrocaw, Poland), the son of Leopold Damrosch, a conductor, and Helene von Heimburg, an opera singer. His father, a converted Jew, and his mother had met in Weimar, where Leopold was concertmaster of the ducal court orchestra led by Franz Liszt and Helene was a leading singer of opera and lieder. Moving to Breslau in 1858 as chief of the Orchesterverein, Leopold soon became a conductor distinguished enough to attract the attention of such luminaries as Liszt, Peter Cornelius, Richard Wagner, Carl Tausig, Anton Rubinstein, Joseph Joachim, Hans von Bülow, and Clara Schumann, all of whom were Leopold's personal friends. It was into this milieu that Walter Johannes was born.

In 1871 Leopold was offered the position of director of the Arion Society, and the Damrosches immigrated to New York City. There Leopold established himself anew as a conductor of the Arion Society, the Oratorio Society, German opera at the Metropolitan, and occasionally the New York Philharmonic. He also founded the rival New York Symphony Society in 1878.

In this professional atmosphere young Walter not only absorbed the necessary musical skills but also learned the value of diplomacy. He played piano well enough to know the standard repertory and express it with conviction. He mastered all the techniques of score reading, tempo memory, and baton control necessary for the successful conductor. His affability, extraordinary good looks, and articulateness enhanced these prodigious musical skills. When his father became ill, the 23-year-old Walter was therefore ready to step in to take his place. Conducting both Die Walküre and Tannhäuser at the Metropolitan Opera, he launched himself on a career that would last for decades into the twentieth century. In turn, besides conducting at the Metropolitan, he directed the New York Symphony Orchestra (also known as the Symphony Society of New York) and the Oratorio Society (from 1885) and founded the Damrosch Opera Company (1895).

In the 1920s he conducted concerts on radio's "NBC Music Appreciation Hour," and he became music adviser to the National Broadcasting Company in 1927. As a composer Damrosch confined himself to operas, most of which not only were performed but also achieved some degree of critical success: The Scarlet Letter (Boston, 1896), The Dove of Peace (Philadelphia, 1912), Cyrano de Bergerac (Metropolitan, 1913), and The Man without a Country (Metropolitan, 1937). Damrosch himself admitted to the "overwhelming influence of Wagner," and even such a sympathetic observer as Giulio Gatti-Casazza, then manager of the Metropolitan Opera, which awarded a $10,000 prize and production to Cyrano, emphasized the quality of the critic William J. Henderson's libretto and of the singers' performances, rather than the music, though he did say in his Memories of the Opera (1941) that "Damrosch is a good musician with a good experience of the theatre."

Damrosch's greatest talent lay in his ability to organize and sustain large artistic projects by gaining the interest and financial support of wealthy patrons. He became a veritable arts adviser to Andrew Carnegie, the industrialist, who subsequently gave funds for the construction of Carnegie Hall and for a time was president and chief financier of both Damrosch's New York Symphony Orchestra and his Oratorio Society. Damrosch was responsible for the invitation to Tchaikovsky to conduct his own works for the opening of Carnegie Hall in 1891. It was through Carnegie that Damrosch gained entry into the world of society and politics. In 1890 he married Margaret Blaine, daughter of the Republican candidate for president in 1884, James G. Blaine. They had eight children, only four of whom survived to adulthood and one of whom, Gretchen Damrosch Finletter, wrote a book of reminiscences that shows Walter and Margaret to have had a sharing and coequal relationship in which, generally speaking, he would be allowed the last word on artistic affairs; she was the authority on politics.

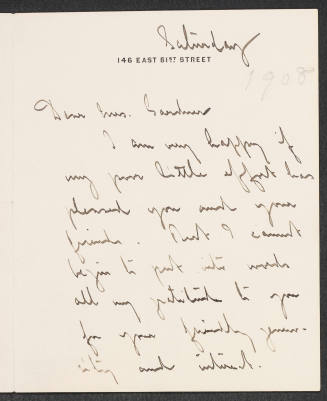

When the New York Symphony Orchestra was reorganized in 1903, Damrosch persuaded Harry Harkness Flagler, scion of two famous oil families, to become its patron. As permanent conductor, Damrosch introduced Sunday afternoon concerts to New York and took the symphony to every part of the United States, often to cities where a symphony orchestra had never been heard before.

During the American participation in World War I, Damrosch was a cultural ambassador to France, where he conducted concerts in Paris and later organized a bandmasters' training school for General John J. Pershing. He set in motion a series of events that included the first tour of Europe by an American orchestra (the New York Symphony Orchestra) and the founding of the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau, where Nadia Boulanger would nurture a generation of young American composers.

Like his father, Damrosch introduced many significant pieces to the American public by such composers as Ralph Vaughan Williams (the London and Pastoral symphonies), Jean Sibelius (Tapiola and the Fourth Symphony), Maurice Ravel (Daphnis et Chloë), and Arthur Honegger (Pacific 231). He conducted the premieres of Ernest Bloch's symphonic poem America, George Gershwin's Concerto in F (which Damrosch had commissioned), and many other American works by composers such as George W. Chadwick, Henry K. Hadley, Daniel Gregory Mason, John Alden Carpenter, Deems Taylor, Edward Burlingame Hill, and Aaron Copland.

During his professional career, Damrosch had the misfortune to stand comparison with some of the finest conductors in the world who were induced to come to the United States: Anton Seidl, Gustav Mahler, Wilhelm Gericke, Karl Muck, and Arturo Toscanini. Furthermore, he inherited the baggage of his father's bitter rivalries, such as that with the conductor Theodore Thomas. As a result, his successes seemed automatically to inspire hostility among influential critics like Henry T. Finck, a longtime admirer of Thomas. Finck once wrote that while Seidl devoted "body and soul" to his conducting, Damrosch could direct both Tristan and Die Meistersinger on the same day and come off looking "cool as a cucumber."

Later opinion was not as harsh. In fact, even the sometimes querulous Virgil Thomson said in 1942 that Damrosch "got the loveliest sound out of the Philharmonic I have ever heard anybody get" (The Musical Scene, p. 42). Some observers found Damrosch's habit of making comments about the music he was about to conduct annoying. Like an evangelist, he used the force of his personality to try to make the inherent difficulties of his subject seem less onerous and even more exciting to first-time audiences and children. From 1928 to 1948, as the radio apostle of good music he did more to make the United States the locus of twentieth-century musical activity than any other figure save perhaps Leonard Bernstein. Damrosch died at his home on Manhattan's East Side.

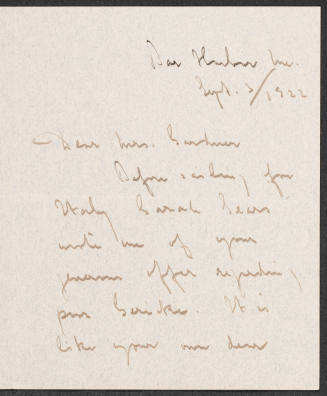

Damrosch was lauded during his lifetime with decorations from the French, Italian, Belgian, and Spanish governments; the silver medal of the Worshipful Company of Musicians of London; and the gold medal of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1922 several of his colleagues gave a concert to raise funds for the Walter Damrosch Fellowship in Music at the American Academy in Rome. Damrosch was president of the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1927-1929 and 1936-1941) and the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1941-1948), and he was the first president of the Musicians Emergency Fund (1933-1943).

In 1959 the city of New York established Damrosch Park in Lincoln Center on a 2.5-acre site next to the Metropolitan Opera House. It was dedicated to the "distinguished family of musicans"--Leopold, Frank Damrosch, and Walter Damrosch, Clara Damrosch Mannes (Walter's younger sister), and her husband David Mannes, founders of the Mannes College of Music.

Bibliography

Walter Damrosch's papers are in the Music Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Damrosch's autobiography, My Musical Life (1923; rev. ed., 1930), provides a selective factual account and should be read together with Lucy Poate Stebbins and Richard Poate Stebbins, Frank Damrosch: Let the People Sing (1945), for a more complete account of the family, especially its origins. Three doctoral dissertations deal largely with Damrosch's cultural and educational activities: Frederick Theodore Himmelein, "Walter Damrosch, a Cultural Biography" (Univ. of Virginia, 1972); William Ray Perryman, "Walter Damrosch: An Educational Force in American Music" (Indiana Univ., 1972); and M. Elaine Goodell, "Walter Damrosch and His Contributions to Music Education" (Catholic Univ. of America, 1973). For insight into his private life, see his daughter Gretchen Damrosch Finletter's From the Top of the Stairs (1946). W. J. Henderson, "Walter Damrosch," Musical Quarterly 18 (Jan. 1932): 1-8, is an objective but friendly evaluation written by the professional music critic who collaborated with Damrosch as his librettist for Cyrano. George Martin, The Damrosch Dynasty: America's First Family of Music (1983), provides a "kaleidoscopic . . . saga" of three generations of the Damrosches that helps place Walter's life in the context of his famous family.

Victor Fell Yellin

Online Resources

"Sic Vita" by Walter Damrosch

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mussm:@field(AUTHOR+@band(Damrosch,+Walter.+))

From the Library of Congress's American Memory website. A viewable score of Damrosch's composition in madrigal style "Sic Vita."

Back to the top

Citation:

Victor Fell Yellin. "Damrosch, Walter Johannes";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00275.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:15:30 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.