George Dewey

Dewey, George (26 Dec. 1837-16 Jan. 1917), naval officer, was born in Montpelier, Vermont, the son of Julius Yemans Dewey, a prominent physician and insurance company president, and Mary Perrin. His mother died when Dewey was just five years old. After study at Norwich University, Dewey entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1854. The rambunctious plebe accumulated 113 demerits during his first year at the academy, but he graduated in 1858, fifth in his class of fifteen. After a cruise in the Mediterranean on the new frigate Wabash, he was commissioned a lieutenant and third in his class in April 1861.

Through the Civil War, Dewey served as executive officer on six major ships in eight campaigns as well as on patrol and blockade duty. While Dewey was executive officer on the old side-wheeler Mississippi during David G. Farragut's assault on New Orleans, his skipper entrusted him with navigating the ship on its dangerous movement through the barrier between Forts Jackson and St. Philip below the city. A year later, when the Mississippi's pilot ran it at full speed on a mud bank before Confederate batteries at Port Hudson, Dewey supervised evacuation of the crew under heavy enemy fire. After a stint on Farragut's flagship, the screw sloop Monongahela, on the lower Mississippi, Dewey served in 1864 on the third-rate, double-ended gunboat Agawan on the James River. He finished the war as executive officer on the regunned frigate Colorado during the attacks on Fort Fisher in December 1864 and January 1865. He then held the rank of lieutenant commander.

The twenty-five years following the Civil War were for Dewey years of honorable service, slow promotions, and little opportunity to demonstrate distinction. In 1866 he sailed for Europe on the screw sloop Kearsarge, famed victor over the Confederate raider Alabama. This was followed by brief spells as executive officer on the sloop Canandaigua, as flag lieutenant for the commander of the European Squadron, and as executive officer of the Colorado. In 1867 he joined the faculty at the Naval Academy, and that year he married Susan Boardman Goodwin, the daughter of a former governor of New Hampshire. She died in 1872, five days after giving birth to their only child, George Goodwin Dewey. Dewey's first command (1870-1871), the third-class sloop Narragansett, was cut short when he was ordered in January 1871 to the Supply, one of three vessels designated to carry relief to French victims of the siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War. After an assignment at the Torpedo Station in Newport, Rhode Island, Dewey immediately secured command once more of the Narragansett in 1873 and spent two years surveying the Gulf of California and the west coast of Mexico. For the next six years he was ashore with the Lighthouse Service at Boston (1875-1878) and as secretary of the Lighthouse Board in Washington (1878-1882).

By 1882 Dewey was bound for the Asiatic Station in command of the old sloop Juniata. At Malta, however, he was stricken with typhoid and an abscess on the liver and was put ashore in a British hospital. After an extended sick leave and promotion to captain, in 1884 he briefly commanded the cruiser Dolphin, the smallest of the first four ships of the steam and steel navy. When the Dolphin failed its initial trials, Dewey was given command of the steam sloop Pensacola, flagship of the European Station, from 1885 to 1888.

Dewey in 1889 began a four-year term as chief of the Bureau of Equipment at the Navy Department. He continued his comfortable Washington career with appointments on the Lighthouse Board, eventually holding the presidency (1893-1895). In October 1895 he was named president of the Board of Inspection and Survey. While with the latter board, he presided over inspections of five of the navy's first six battleships and in the spring of 1896 received his commission as a one-star commodore. Thanks in part to backing from the young assistant secretary of the navy, Theodore Roosevelt, Dewey commanded the Asiatic Squadron and broke his commodore's penant on his flagship, the Olympia, in Nagasaki Harbor on 3 January 1898.

Naval plans were already prepared for an attack on Manila should war break out between the United States and Spain. On 5 February 1898, just ten days after the sinking of the battleship Maine at Havana, Roosevelt alerted Dewey by a telegram marked "secret and confidential" that he should concentrate six ships of his command, all except the antiquated gunboat Monocacy, at Hong Kong and keep them coaled. Roosevelt further directed that, should war break out, Dewey was to prevent the Spanish squadron from leaving the Asiatic coast to attack the Philippines. At Hong Kong Dewey prepared his ships for action, impressed the new revenue cutter McCulloch into his service, and purchased the collier Nanshan and the British steamer Zafiro to transport supplies. Upon arrival of the cruiser Baltimore with much needed ammunition on 22 April, Dewey's squadron clearly outclassed the ships of the opposing Spanish in tonnage, speed, and gun power. He had assembled his ships at Mirs Bay, thirty miles up the China coast from neutral British Hong Kong, when on 24 April the Navy Department directed him to push ahead with "utmost endeavors" against the Spanish fleet and the Philippines.

After determining that the Spanish admiral, Patricio Montojo, was not waiting for him at Subic Bay, thirty miles to the north of Manila Bay, Dewey at midnight on 30 April led his five cruisers and single gunboat with attending train through Boca Grande into Manila Bay, without heed to possible mines or enemy shore batteries. At 5:00 a.m. the commodore sighted Montojo's ships drawn up before the naval station at Cavite to the southwest of Manila, and at 5:35 a.m., on the bridge of the Olympia, he calmly advised the flagship's skipper, Captain Charles V. Gridley, "You may fire when you are ready Gridley." The Americans passed three times to the west and twice to the east, firing into the Spanish ships. When at about 7:35 a.m. the Americans withdrew into the bay to count their ammunition, the Spanish ships were in flames and sinking. Dewey returned to battle at 10:50 a.m. Within two hours every Spanish ship was out of action, and the guns ashore at neighboring Sangley Point were silenced. After Dewey threatened to bombard the city, the Spanish halted their futile fire from Manila and surrendered the guns and magazines at the entrances to the bay on 2-3 May. Dewey cut Manila's cable link with the outside world when the Spanish governor general refused to extend its use to the Americans. In due course, the commodore dispatched the McCulloch to Hong Kong with a message for transmission to Washington announcing his destruction of the Spanish squadron. He also reported that, while he could take Manila at will, he could not hold the city.

Even before receiving Dewey's victory messages, President William McKinley had decided to dispatch an army expeditionary force to Manila along with the cruiser Charleston and the monitors Monadnock and Monterey. Spain, however, also responded by ordering east an outwardly impressive force under Admiral Manuel de la Camara. Madrid recalled the Camara expedition after the American victory at Santiago de Cuba released powerful American ships for possible operations against Spain. Britain, Japan, France, and Germany all sent ships to observe developments at Manila. Especially disturbing to Dewey were the Germans, who by late June had assembled a force under Vice Admiral Otto von Diederichs that surpassed Dewey's squadron in gun power and tonnage and engaged in various mysterious activities.

Ultimately of more serious consequence to Dewey than either the Spanish or the Germans were the Philippine insurgents, who like the Cubans wanted to break away from Spain. Initially, he found it convenient to encourage insurgent operations against the Spanish without, it seems, seriously considering Filipino moves to form a government or their declaration of independence. As American forces increased in Manila Bay, relations between Americans and Filipinos became difficult. The Filipinos had laid siege to Manila, but with the arrival of Major General Wesley Merritt and the Third Army contingent, the American army force of 10,000 men was quite sufficient to occupy and hold Manila without any assistance from the insurgents.

The Spanish proved willing to surrender the city to the Americans if the insurgents were kept out. Through the mediation of the Belgian consul, a charade was worked out whereby on 13 August, after some token firing by the Americans on Fort San Antonio to the south of the city, the Spanish surrendered, and the Americans occupied the city without a fight. Unknown to Dewey, the Spanish government had already accepted an armistice providing that the United States would "occupy and hold the city, bay, and harbor of Manila."

Dewey avoided taking a clear position on the future of the islands. He did advise the president that Luzon was the most important island in the group since, in addition to Manila, it embraced Subic Bay, which he judged the finest location for a naval base. Aware of the disintegration of relations between Americans and Filipinos, especially after Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States by the Treaty of Paris in December 1898, Dewey recommended that a civilian commission be sent to the Philippines on a mission of conciliation. Unfortunately, the first Philippine Commission only began its work in the islands months after the outbreak of hostilities that committed the United States to a long war of conquest. Dewey escaped from this unpleasant small war by securing orders to return to the United States on grounds of ill health.

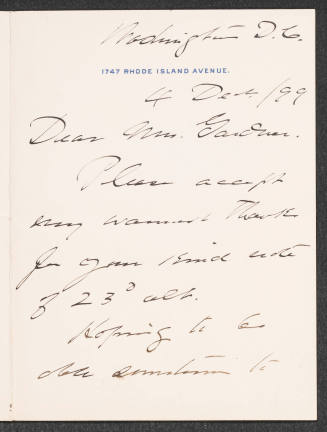

Dewey's victory of 1 May had projected him to a position of immense public adulation. Two weeks after the battle Congress increased the number of rear admirals so Dewey could be given two-star rank. In March 1899 Congress created for him the rank of admiral of the navy with provision that he might remain on active service for life. His triumphal return to the United States was climaxed by a parade down Fifth Avenue in New York, President McKinley's presentation on the steps of the Capitol of a jeweled sword, and the gift from the nation of a mansion in Washington, D.C. In 1899 he married a prominent Washington matron, Mildred McLean Hazen; they had no children. His marriage was not popular, and the public was outraged when Dewey gave his mansion to his new wife. His announcement in March 1900 of his willingness to run for president failed to generate any significant support. A prestigious position was found for the distinguished officer in 1900 when Secretary of the Navy John D. Long appointed him president of the General Board of the Navy, which Long created to serve as the secretary's highest advisory body on naval policy. Dewey's rank as senior officer in either army or navy also brought him the position of senior and presiding officer of the Joint Army and Navy Board, established in 1903, which was in some respects the predecessor of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

During his years as president of the General Board, Dewey and other American naval men were ever alert to the supposed menace of Germany in the Atlantic. In a naval spectacle during the winter of 1902-1903, Dewey assumed command of forces drawn from the North Atlantic, Europe, and South Atlantic to participate in combined maneuvers to test the navy's capacity to meet foreign (German) naval aggression in the Western Hemisphere. With Dewey presiding and Germany in mind, the General Board in 1903 recommended a building program designed to provide the United States by 1920 with forty-eight battleships and an appropriate number of armored cruisers, cruisers, and destroyers. Dewey also strongly supported, over vigorous opposition from conservatives within the service, the shift to construction of the all big gun dreadnought type of battleship.

The advent of Japan as a possible antagonist after 1906 was attended by the most serious challenge to Dewey's views during his seventeen years with the General Board. Since 1898 Dewey had championed Subic Bay as the finest site for an American naval base in the Philippines. In 1906, however, the navy's battleships were concentrated in the Atlantic Fleet, ready to meet an assault from Germany. At the height of the immigration crisis with Japan in June 1907, the Joint Board, with Dewey as senior officer present, resolved that, should war with Japan become imminent, the larger American ships in Asia should withdraw to the eastern Pacific, where they would join the battleships moving from the Atlantic and then proceed to the Philippines. The light naval forces remaining in Asia together with available army forces would join in defense of the still undeveloped base at Subic Bay. The following month President Theodore Roosevelt ordered the Atlantic Fleet to move from the Atlantic to the Pacific in a test of the strategy for war against Japan. The strategy, however, was immediately challenged by Major General Leonard Wood, commanding general in the Philippines, who insisted that Subic Bay could not possibly be held against Japanese attack until the arrival of the fleet from the Atlantic. The Joint Board proposed that the navy continue to use Subic Bay until a base could be constructed on Manila Bay. Dewey and the navy, however, never accepted Manila Bay as the site for the main naval base in the western Pacific. Given the impasse between the army and the navy, the United States built no naval base west of Pearl Harbor before Japan struck on 7 December 1941, perhaps as significant a legacy from Dewey as his victory at Manila Bay.

Except for Subic Bay, Dewey as General Board president avoided identification with rival groups and controversial positions during the Roosevelt and William Howard Taft administrations. A true test of his tact came with the arrival of Woodrow Wilson in the White House and the populist secretary Josephus Daniels in the Navy Department. Somehow Dewey commanded the devotion of both Daniels and Daniels's vigorous critic, Rear Admiral Bradley Fiske, the aide for operations. Dewey apparently escaped unscathed when, at the outset of the new administration, Wilson threatened to abolish both the General Board and the Joint Board if they persisted with recommendations that, he feared, might disrupt his efforts to conciliate Japan. Dewey's skills were again tested after the outbreak of World War I, when Fiske and the advocates of preparedness agitated for measures that seemed to contradict Wilson's determination to avoid any action likely to disturb public opinion. Dewey managed to prevent open collision when he advised that the General Board's recommendations for the fiscal year 1915 be submitted in two letters, an open letter proposing to continue the program of the previous year and an unpublished letter calling for increased personnel. Perhaps because he suspected the new office might render superfluous the General Board and his leadership in the navy, Dewey accepted with some reluctance the new position of chief of naval operations created in 1915.

Infirmities of age notwithstanding, Dewey in October 1915 signed the General Board's recommendation that became the basis for the 1916 program to build a navy second to none. Only days before the passage of this 1916 bill, Dewey gave a final, much-headlined interview to the distinguished newsman George Creel, in which he vigorously defended both the navy and Secretary Daniels. Dewey died in Washington, D.C.

Bibliography

Collections containing Dewey's papers include the George Dewey Papers in the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress; the Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, RG 45, National Archives; and the General Board Records, National Archives. Dewey wrote The Autobiography of George Dewey (1916). See also Ronald Spector, Admiral of the New Navy, the Life and Career of George Dewey (1974); William R. Braisted, The United States Navy in the Pacific, 1897-1909 (1958); and Braisted, The United States Navy in the Pacific, 1909-1922 (1972).

William R. Braisted

Back to the top

Citation:

William R. Braisted. "Dewey, George";

http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00154.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:19:46 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.