Ruth Draper

Draper, Ruth (2 Dec. 1884-30 Dec. 1956), actor/monologist, was born and raised in New York City, the daughter of William H. Draper, a physician, and Ruth Dana, his second wife. Her maternal grandfather was Charles A. Dana, editor and part owner of the New York Sun, and her parents were affluent as well as educated. The seventh of William Draper's eight children (he had had two by a previous marriage), Draper was a shy, frail child, and school disagreed with her. Her parents hired a German governess, Hannah Henrietta Hefter, to school her at home, and it was thanks to Hefter that Draper carried a love of literature and languages throughout her life and work.

From an early age Draper showed a talent for impersonation, which eventually led her to develop character sketches that she performed in programs before wealthy New Yorkers beginning in 1902. In 1910 the pianist Ignace Jan Paderewski, a family friend, encouraged her to turn professional. Against her mother's wishes she decided to do so and began to develop a more extensive repertoire. By 1913 she was performing for the elite of London. After one of her performances, Queen Mary wrote in her diary that Draper recited "too delightfully."

Not a conventional actress, Draper rarely performed material that she did not write herself. Early on she played a lady's maid in A Lady's Name, starring Marie Tempest, in 1916, and in 1917 she appeared in August Strindberg's The Stronger, which ran on the same bill with her own sketch, The Actress, a piece that came to be viewed as one of her most brilliant character sketches. But reviews and her own strong feelings convinced Draper that she should confine herself to her own material. According to Neilla Warren, editor of Draper's letters, except for a couple of roles in a few all-star benefits in later years, after 1917 Draper never appeared in a program that she did not create for herself.

Draper's performances consisted of combinations of various five- to fifty-minute character sketches in which she often played multiple characters--and evoked many others--with the help of only a few props, hats, and shawls. Both dramatic and comic sketches found their way into her repertoire, which she continually expanded with new sketches until about 1940, after which she relied on older material. Draper was careful to acknowledge her debt to comedienne Beatrice Herford, whom she had seen in 1912 in a minimal production of The Yellow Jacket, staged with no scenery and few props. Draper appeared at the White House and began a series of foreign engagements; she was equally popular in the United States and Europe, owing in part to her ability to speak several languages, including French, in which she was fluent. Late in life, in 1955, she performed for three weeks with her nephew, dancer Paul Draper.

A few of Draper's popular character sketches included "The Actress," "Vive la France!," "A Scottish Immigrant at Ellis Island," "The Italian Lesson," and "The German Governess." As her obituary in the New York Times opined, Draper, "like most great artists, . . . had imitators, but probably no equal in the art of creating taut one-woman shows. The emotional range of her thirty-seven sketches and fifty-eight characters was as extraordinary as her devotion to her work." Much of Draper's material was derived from personal experience, obtained through extensive travel and keen powers of observation. Many of her monologues were recorded on a five-volume disk collection entitled The Art of Ruth Draper (Decca, 1954-1955).

Draper never married, but she had a passionate--though short-lived--affair with Lauro deBosis, a brilliant poet, scientist, and antifascist Italian revolutionary. Seventeen years her junior, deBosis happened into Draper's life when she was forty-three, and the couple spent only three and a half years together. DeBosis was killed in 1931 after a flight over Rome, during which he dropped 400,000 antifascist pamphlets on the city. Draper never completely recovered from his death. She convinced Oxford University Press to publish The Golden Book of Italian Poetry, a collection of poems deBosis had edited, and she translated his play, Icaro, into English and later had it translated into French. In 1934 she also set up, at Harvard, the Lauro deBosis Lectureship in the History of Italian Civilization, which continues to fund important Italian scholars.

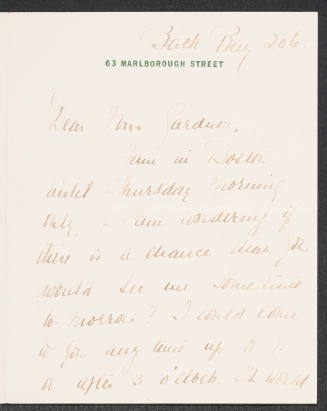

Although Draper looked upon New York and London as her theatrical homes, by the end of her life she had performed on all five continents, in most of the countries of the world, always with great success. A map of what Draper called her "strange wandering life"--in which each place in the world that she visited is marked with a gold star--is in a special reading room for children of members of the New York Society Library. Draper's friends, including notables in the arts and in society, were scattered across Europe, Great Britain, and North America.

Committed to helping those in need, Draper gave numerous benefit performances for various charities, including but not limited to churches, the Red Cross, and the Actors Benevolent Fund. In 1951 King George VI of England conferred upon her the Insignia of Honorary Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in recognition of her generosity to British philanthropies, especially during and after World War II; he also awarded her the honorary title of C.B.E. Draper received several honorary degrees from U.S. and British universities, including Cambridge University.

Draper died in her sleep at her New York apartment following a performance at the Playhouse Theatre. Her influence continues to be felt. Illustrious one-woman shows, including those of Lily Tomlin and Anna Deveare Smith, can be compared to the versatile performances that Draper gave nearly half a century before. Sometimes lonely, always full of dignity, Draper committed herself to performing but also to good works. Her letters are the succinct yet compassionate expressions of a citizen of the world during the first half of the twentieth century. She so impressed her friend and contemporary Lugné-Poë that he wrote, "I have never met an actress so sincerely humble when she steps out of her profession, whose success however she perfectly admits. . . . In my eyes she is always a great woman" (quoted in Warren, p. 38).

Bibliography

The most satisfying volume for studying Draper is The Letters of Ruth Draper 1920-1956, compiled and edited, with narrative notes, by Neilla Warren (1979). Also extremely helpful is The Art of Ruth Draper, both the book by Morton Zabel (1960), which includes a biography and many of Draper's monologues, and the five-volume set of disk recordings by Spoken Arts. Various references to Draper are included in Arthur Rubinstein, My Young Years (1973); Joyce Grenfell, Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (1976); Alexander Woollcott, Going to Pieces (1928); and Malvina Hoffman, Heads and Tails (1965). An obituary is in the New York Times, 31 Dec. 1956.

Cynthia M. Gendrich

Back to the top

Citation:

Cynthia M. Gendrich. "Draper, Ruth";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00322.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:23:43 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.