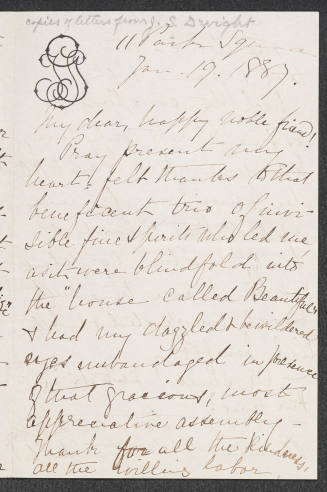

John Sullivan Dwight

Dwight, John Sullivan (13 May 1813-5 Sept. 1893), music critic, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of John Dwight, a physician and radical freethinker, and Mary Corey. He attended Boston Latin School and graduated from Harvard College in 1832, where he was active in its musical club, the Pierian Sodality; in 1836 he graduated from Harvard Divinity School. Along with friends from Harvard, he was an original member of the Transcendental Club; its members' religious, literary, and philosophical views, reflecting the influence of Immanuel Kant, pitted them against the prevailing Calvinist orthodoxy and Unitarian rationalism. He was also an early follower of Associationism, a movement based on precepts of universal harmony advanced by the utopian philosopher Charles Fourier. Dwight's thinking on music was a synthesis of the two philosophies. His root concept, first expressed in his 1835 essay "On Music," was simple: words were the language of thought; music was the language of feeling. He wrote that

music is both body and soul, like the man who delights in it. Its body is beauty in the sphere of sound--audible beauty. But in this very word beauty is implied a soul, a moral end, a meaning of some sort. . . . This beauty . . . results from the marriage of a spiritual fact with a material form. . . . [In music] the material part, which is measured sound, is the embodiment and sensible representative, as well as the re-acting cause, of that which we call impulse, sentiment, feeling, the spring of all our action and expression. In a word, it is the language of the heart.

In 1841, after a brief stint as minister of the Unitarian church in Northampton, Massachusetts, he resigned and joined Brook Farm, a community based on Associationist principles. There he took charge of the musical life of the community and became one of the principal contributors to its journal, The Harbinger. It was largely through Dwight's writing that music came to occupy an important place in transcendentalist thought. He argued that music had social functions of the greatest importance: to make men familiar with the beautiful and the infinite, to excite common feeling, to create common associations, and to unite individuals in common sympathies found in things eternal. He held that the conventional distinction between sacred and secular music was false, and that great music in itself was the language of natural religion and could help in building harmonious communities. But by his standards, not all music was equally qualified to convey these aesthetic, spiritual, and moral values. He regarded instrumental music as the highest form of pure musical expression, arguing that opera, with its inclusion of text and visual drama, "errs in undertaking the same office with her sister, speech, which is the voice of understanding and describes facts." He had even less regard for programmatic and popular music. According to his prospectus for The Harbinger, the journal would give little attention to "mere musical trifles"; rather, it would "constantly notice and uphold for study and for imitation music which does not merely seek to amuse, but which is the most enlightened outpouring of the composer's life," the most exemplary composers of which were Handel, Mozart, and, above all, Beethoven.

After the 1847 breakup of Brook Farm, Dwight returned to Boston where he directed an Associationist choir, lectured on musical matters, and served as a reviewer and music critic for journals there and in New York. In 1851 he married Mary Bullard, a member of his choir; they had no children. That same year he served briefly as musical editor of the Boston Commonwealth. The following year he gained the assistance of the Harvard Musical Association in launching Dwight's Journal of Music; he served as its sole editor until 1881, when publication ceased. The journal became America's most influential musical periodical; its circulation nationally at one time reached over fifteen hundred. The most frequent contributor of the journal's essays on music history, theory, and education, translations of important European musical writings (mostly German and French), concert and new music reviews, and national and international musical news and correspondence was Dwight himself. He continued to champion the music of Bach, Handel, Mozart, and Beethoven, while admonishing his readers that their judgments must not be swayed by the amiable applause of a miscellaneous audience. He was generally unsympathetic to contemporary American composers such as William Henry Fry and George Bristow and did not hesitate to use the pages of his journal to inveigh against the "narrow nationality" he found in their works. He was also critical of the concert works of another American, Anthony Philip Heinrich, whom he dismissed as one of those Romantics "who wish to attach a story to every thing they do." Although he had initially praised Negro minstrel melodies as "truly beautiful," he became vehement in his opposition as Stephen Foster's "Old Folks at Home" swept the country. Such tunes, he fumed, were "morbid irritations of the skin" that intruded on the taste for "better" music.

His canon of "better music" also excluded that of Richard Wagner, whose music dramas represented the musical avant-garde of the time. He was distressed by their "enormous orchestration, crowded harmonies, sheer intensity of sound, and restless, swarming motion without progress [that] seem to seek to carry the listeners by storm, by a roaring whirlwind of sound." But despite his antipathy to Wagner's music, Dwight allowed laudatory articles about it to appear in his Journal.

Financing his musical enterprises was a problem throughout his life. The music publisher Oliver Ditson took over the publishing of the Journal in 1858, but declining revenues and readership eventually forced its demise. At the height of its influence during the 1860s and early 1870s, however, Dwight was known as "the Autocrat of Music." Despite his biases, he played an important role in the development of American musical life.

His wife died in 1860 while he was away on his only trip to Europe. From 1873 to his death in Boston, he served as president and librarian of the Harvard Musical Association, where he also had his dwellings.

Bibliography

Dwight's biographer was a younger contemporary of the transcendental coterie: George Willis Cooke, John Sullivan Dwight: Brook-Farmer, Editor, and Critic of Music (1898; repr. 1973). For Dwight's contributions to transcendental views of music, see Irving Lowens, Music and Musicians in Early America (1964), pp. 257-61. Betty E. Chmaj, "Fry versus Dwight: American Music's Debate over Nationality," American Music 3 (1985): 62-84, delineates the position Dwight held as defender of conservative Europeanism against Fry and other champions of Americanism. Two dissertations contain more detailed explications of Dwight's writings and views: W. L. Fertig, "John Sullivan Dwight, Transcendentalist and Literary Amateur of Music (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Maryland, 1952), and W. W. Lebow, "A Systematic Examination of the Journal of Music and Art Edited by John Sullivan Dwight" (Ph.D. diss., UCLA, 1969). Dwight speaks for himself throughout the pages of Dwight's Journal of Music (1852-1881; repr. 1968).

Jean W. Thomas

Back to the top

Citation:

Jean W. Thomas. "Dwight, John Sullivan";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00345.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:25:54 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.