William Crowninshield Endicott

Salem, 1826 - 1900, Boston

In 1853 Endicott established his own practice with Jairus Ware Perry, and for the next twenty years the firm of Perry and Endicott dominated the legal scene in Essex County, Massachusetts. Endicott argued the cases in court, and Perry performed the office work and legal research. Endicott also became active in local politics and served as a member of the Salem Council in 1852, 1853, and 1857. During his last term he was elected president of the council and in 1858 became the Salem city solicitor. Ideologically, Endicott began his political career as a Whig, but he became a Democrat in 1856 when the Whig party collapsed.

During the Civil War period, the Massachusetts Democratic party was always in the minority, and, as a result, Endicott did not fare well in electoral politics. After retiring from his position as city solicitor in 1863, Endicott lost three bids for the position of Massachusetts attorney general in 1866, 1867, and 1868. Endicott then ran for Congress in 1870 and again was defeated. Finally, Governor William B. Washburn, a Republican, appointed Endicott to the supreme judicial court in 1873 after the General Court of Massachusetts increased the number of associate justices to six. During his nine years on the bench, Endicott wrote 378 opinions, and not one was overruled during his lifetime.

Eventually, in 1882, the strain of public life took its toll, and Endicott resigned from the public bench owing to ill health. He spent the next eighteen months traveling in Europe and returned to the United States in 1883 to resume his private law practice in Salem. His respite from politics, however, did not last long. In 1884 the Democratic party petitioned him to run for governor. At first he refused, but eventually he relented with the understanding that he would make no public speeches during the campaign. The Democratic party leadership in Massachusetts believed that Endicott, a patrician who had never been allied with the machine, would be a strong candidate, but in the end he lost again in this strongly Republican state.

Like his earlier political losses, defeat did bring Endicott public exposure, which brought additional opportunities. In February 1885 Grover Cleveland offered him a position in his cabinet as secretary of war. It was in this position that Endicott would have the greatest impact on the history of the country. With Geronimo's surrender in 1886 and the conclusion of the Indian wars, the War Department could begin to attend to other matters: namely, internal reform and coastal defense. As a reformer, Endicott sought to improve the promotion process by proposing legislation requiring officers to pass an examination as a condition for promotion. He also attempted to lower the number of desertions from the army by petitioning Congress to enact legislation that granted police or private citizens the authority to arrest deserters.

Endicott's greatest legacy as secretary of war, however, was the Endicott Board of Fortifications. The board was convened in 1885 by President Cleveland in response to warnings by General Philip T. Sheridan and other military experts that new advances in rifled guns and gunpowder had rendered the country's coastal fortifications obsolete. After studying ports along both coasts and the Great Lakes, the Endicott Board recommended a $126 million program of fortification construction in twenty-seven major ports, including New York, San Francisco, Boston, the Great Lakes ports (including the St. Lawrence River), Hampton Roads, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore, Portland, and Narragansett Bay. The program was designed to protect cities against invasion, bombardment, and blockade. It called for the procurement of a large variety of expensive weapons to accomplish these diverse goals: floating batteries, large guns in heavily armored turrets, twelve-inch rifled mortars, torpedo boats, mines, electric cables, and searchlights.

By the program's conclusion in 1905, however, only $30.7 million had been appropriated for the project. Most of this cost reduction came from substituting shielded casemates, large guns, and floating batteries with light, dispersible, rapid-fire, high-powered guns. The genius of Endicott's plan was that it was flexible enough to adapt to changing military and technological conditions.

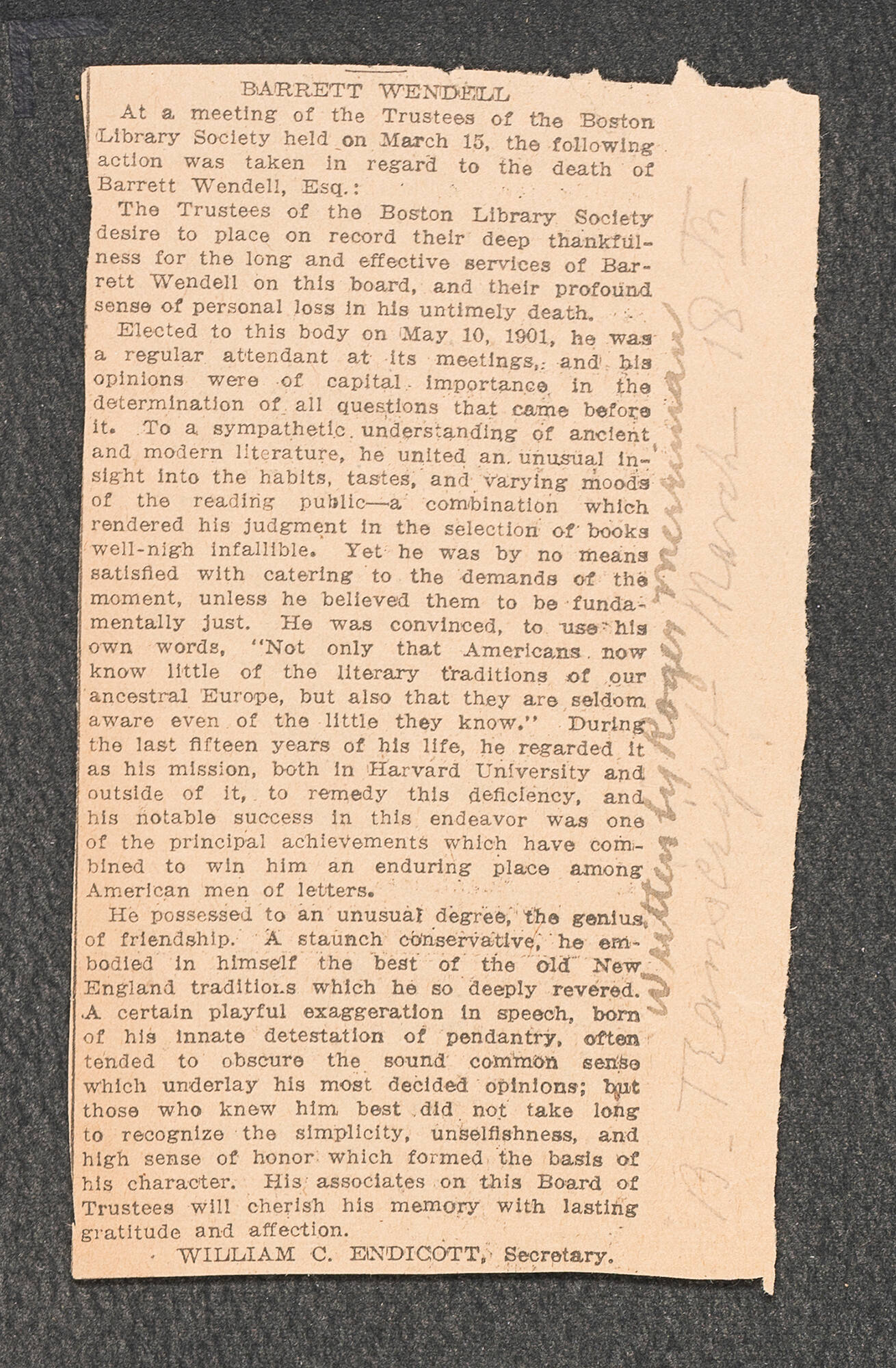

Endicott resigned with the Cleveland administration in 1889 and devoted the rest of his life to numerous charity efforts. Among other activities, he served as trustee of the Groton School, president of the Peabody Academy of Science, and president of the Harvard Alumni Association. Having married a wealthy cousin, Ellen Peabody, in 1859 and also having inherited money of his own, Endicott lived a patrician lifestyle during his final years, shuttling among residences in Boston, Danvers, and Salem. He had two children.

The day after Endicott's death in Boston, Secretary of War Elihu Root issued General Orders Number Sixty-nine to announce his death. In Root's words, Endicott was appointed to a position that, "though foreign to his training, he immediately rendered conspicuous by strict attention to duty and a keen interest in the army and its requirements." While it could be argued that Endicott's legal and political training prepared him well for the position of secretary of war, it is difficult to contest Root's claim that Endicott served admirably in this role. He initiated a reform process that eventually would flourish under Root. More significantly, his board report alerted the country to its strategic vulnerabilities and provided a road map for the construction of an effective system of strategic defense.

Bibliography

The personal papers of Endicott are held by the Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Essex, Mass. Official records of Endicott's term as secretary of war are at the National Archives. The most complete narrative of Endicott's life is Charles Francis Adams, Memoir of William C. Endicott, LL.D. (1902). For information on the Endicott Board, see Rowena A. Reed, "The Endicott Board--Vision and Reality," Periodical Journal of the Council on Abandoned Military Posts 11, no. 2 (Summer 1979): 3-17; and Edward Ranson, "The Endicott Board of 1885-86 and the Coast Defenses," Military Affairs 31, no. 3 (July 1967): 74-84.

John Darrell Sherwood

Back to the top

Citation:

John Darrell Sherwood. "Endicott, William Crowninshield";

http://www.anb.org/articles/05/05-00216.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:32:24 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Salem, Massachusetts, 1860 - 1936, Squam Lake, New Hampshire

American, 1869 - 1944