Minnie Maddern Fiske

found: Thackeray's "Vanity Fair" ... 1899.

found: Her Mrs. Fiske, 1968 (Mrs. Fiske)

found: Minnie Maddern Fiske, 1962 (Minnie Maddern Fiske)

found: Amer., c1975 (Fiske, Minnie Maddern, 1865-1932; b. as Marie Auguster Davey; stage name: Minnie Maddern; m. to Harrison Grey Fiske)

Fiske, Minnie Maddern (19 Dec. 1864?-15 Feb. 1932), actress, playwright, and director, was born Marie Augusta Davey in New Orleans, Louisiana, the daughter of Thomas Davey, an actor-manager, and Minnie Maddern, a musician and actress. As an infant she performed during the entr'actes in her parents' company. Her dramatic debut occurred at the age of three, as the duke of York in Richard III. A succession of child parts followed, and she became a prodigy patterned after Lotta Crabtree and Clara Fisher (Clara Fisher Maeder), appearing opposite major performers of the 1860s and 1870s, including Laura Keene, Junius Brutus Booth, Barry Sullivan, Carlotta Leclercq, Edward Loomis Davenport, Sarah Scott-Siddons, Emma Waller, and Joseph Jefferson. Her parents separated when she was very young, and she was in her mother's custody during this period of intense touring and New York apprenticeship. Many accounts acknowledge that she was educated in convents in Cincinnati, St. Louis, and possibly Montreal, but the chronology is uncertain and formal schooling was minimal. Following her mother's death in 1879, she was raised by her maternal aunt Emma Stevens, whose daughter Emily Stevens also had a stage career.

Fiske's apprenticeship exposed her to a wide range of parts requiring skill in tragedy, melodrama, comic opera, travesty roles, and even the old woman line of business (the Widow Melnotte in Edward Bulwer-Lytton's The Lady of Lyons). She became a full-fledged star in 1882-1883 with the success of Fogg's Ferry, by Charles E. Callahan, and Caprice, by Howard Taylor (1884), "protean pieces" patterned after her unique talent. During the tour of Fogg's Ferry she wed one of the orchestral musicians, LeGrand White. This marriage was brief. Until her second marriage to Harrison Grey Fiske (a playwright and the editor and publisher of the New York Dramatic Mirror, the leading trade paper) in 1890 she was always known professionally as Minnie Maddern.

The actor and dramatist Dion Boucicault described Fiske as "no radiant Juliet, no stately Pauline, no majestic Parthenia. Here is only an odd morsel of humanity, half child, half woman; a creature with thin, wiry body, a pale face, nervous lips and wonderful eyes" (quoted in John Bouvé Clapp and Edwin Francis Edgett, Players of the Present [1899-1901], pp. 109-10). This explains her attraction as a child and ingenue performer. During the first three years of her marriage to Fiske she did not appear on stage but composed several plays (including The Rose, The Eyes of the Heart, Fontenelle, A Light for St. Agnes, and Countess Roudine), most of which were produced. During this sabbatical she came under the influence of European modernists, observing Eleonora Duse on her first American tour and following the controversies surrounding Henrik Ibsen's plays, especially during the 1889-1894 seasons. She resumed acting in late 1893 in her husband's play Hester Crewe; shortly after she was acclaimed as Nora in Ibsen's A Doll's House in a single benefit performance.

During the rest of the 1890s Fiske's repertoire alternated between the "advanced drama"--most notably adaptations of Thomas Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1897) and William Makepeace Thackeray's Vanity Fair (Becky Sharp, 1899)--and the most frivolous plays of the established repertoire, such as Frou-Frou (1894) and Divorçons (1897). This is typical of Ibsen's champions; the same pattern is evident in Janet Achurch and Elizabeth Robins, actresses who did much to promote opportunities for psychologically realistic acting and for new playwrights in England, while making their living in trivial comedies and outdated melodramas. Equal strength in comedy and tragedy, therefore, helped to forge the new hybrid style. Fiske's contribution to the history of acting in the United States was to foreground the internal processes of characters, giving subtext precedence over overt signals such as asides or monologues. She specialized in playing women who would not or could not speak about what they knew, and so she had to develop methods (such as pauses and nonlinguistic sounds) to indicate their state of mind.

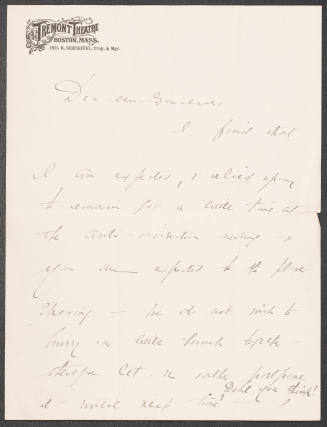

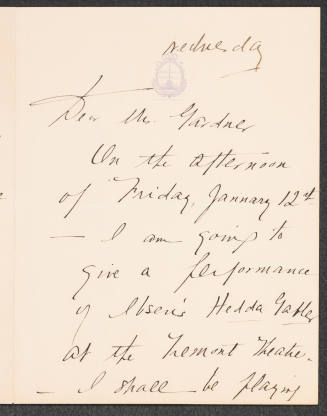

In 1901 the Fiskes embarked on the management of the Manhattan Theatre, establishing a company that aimed to bring the ideals of ensemble acting and minute attention to every detail of production to the United States. The repertoire was not exclusively modernist, but productions of Hedda Gabler, A Doll's House, Rosmersholm, Paul Heyse's Mary of Magdalene, and Langdon Mitchell's The New York Idea paralleled the objectives of the European free theater movement until the experiment collapsed as a resident company in 1906-1907 (tours continued until 1914). In 1908 she produced Salvation Nell, a play by Edward Shelton, the first product of George Pierce Baker's Harvard course to reach Broadway. Her performance was infamous for the sequence in which she held her drunken lover's head in her lap, motionless and silent, for ten minutes.

Unlike most players of the period, Fiske was not in the employ of the Theatrical Syndicate, which, from 1896, controlled a large number of theaters and forced companies to accept its dates, routes, and terms. This had two chief implications: first, she tried to surround herself with an entire complement of skilled performers, eschewing the single "star" system, and second, she had no access to booking the vast majority of bona fide theaters in New York and throughout the nation. The Fiskes' opposition to the Syndicate's star vehicles and stranglehold on real estate forced them to hire venues completely out of keeping with Minnie's fame. When an entente was reached in 1909 and the Syndicate allowed Salvation Nell to be booked into their theaters on independent terms, a series of critical but not financial successes ensued. They were forced to sell the New York Dramatic Mirror in 1911, and Harrison declared bankruptcy in 1914. By this time the couple were estranged and had parted on amicable terms; years of touring kept her on the road while he remained in New York.

Fiske appeared in at least two film versions of her stage roles, as Tess in Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1913) and as Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair (1915), but after 1915 she stuck to live performance. Revivals and potboilers paid the bills, but productions by Elmer Rice, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and Shakespeare are also notable. Her last performance occurred in Chicago late in 1931. She collapsed and three months later died at her home in Long Island, ending a sixty-five year career.

Fiske's acting has been described in diametrically opposed ways: stagey and nervous as well as consummately true to life. Her voice was sometimes criticized for overemployment of staccato passages and other times for slurring, though whether the power and control she acquired working in huge mid-nineteenth-century theaters had simply gone out of vogue or whether she was indulging in idiosyncrasy for growing naturalist tastes is impossible to definitively determine. She was conscious of the rules of acting and so could deliberately break them--such as speaking while facing upstage--paradoxically garnering the audience's full attention when a more orthodox actor might simply have been judged inept. Toward the end of her career, her technique of subtextually evoking characters' emotional lives had been absorbed into the general acting vocabulary; when she ceased to innovate, these "signatures" that she had taught audiences to recognize and appreciate seemed like clichéd claptraps from a bygone era. Her directing skills, particularly in the first decade of the twentieth century, brought her theater in line with the practices of the Moscow Art Theatre under Stanislavsky, though this was a coincidence. Her playwriting represents some of the first attempts to create an Americanized idiom in the realist school, capitalizing on Ibsen's and Duse's lead in creating complex characterizations for actresses.

Fiske had no biological children but in 1922 adopted an abandoned infant whom she named Danville Maddern Davey. She was an activist on behalf of animal rights, opposing trapping, bullfighting, and abuse of cart horses, serving as the first vice president of the International Humane Association. She was honored by Smith College in 1926 for being "the foremost living actress" and received the Good Housekeeping Award in 1931 in recognition of being among the twelve greatest living women.

Bibliography

Manuscript materials relating to Fiske are deposited at Harvard College Library (Harvard Theatre Collection), the New York Public Library, the University of Texas at Austin (Hoblitzelle Theatre Arts Library), and the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress also holds materials in the Prints and Photographs Division and the only known copy of the 1915 Kleine-Edison film of Vanity Fair (American Film Institute). Of her plays, only A Light from St. Agnes (1905?) has been published. Mrs. Fiske: Her Views on Actors, Acting, and the Problems of Production, as recorded by Alexander Woollcott, is an important source (1917), along with Archie Binns's biography, Mrs. Fiske and the American Theatre (1955). Recent dissertations include Elizabeth Lindsay Neill, "The Art of Minnie Maddern Fiske: A Study of Her Realistic Acting" (Ph.D. diss., Tufts Univ., 1970); Mary Ann Angela Messano-Ciesla, "Minnie Maddern Fiske: Her Battle with the Theatrical Syndicate" (Ph.D. diss., New York Univ., 1982); and Ellen Donkin, "Mrs. Fiske's 1897 Tess of the D'Urbervilles: A Structural Analysis of the 1897-98 Production" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Washington, 1982). An obituary is in the New York Times, 17 Feb. 1932.

Tracy C. Davis

Back to the top

Citation:

Tracy C. Davis. "Fiske, Minnie Maddern";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00397.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:38:21 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.