Desmond FitzGerald

found: His Desmond's rising : memoirs, 1913 to Easter 1916, 2006 : t.p. (Desmond FitzGerald) p.9 (Thomas Joseph or Tommy was b. in Feb. 1888 ... in his teens Tommy decided to call himself 'Desmond')

found: McRedmond, L. Modern Irish lives, 1996 : (FitzGerald, Desmond, 1888-1947)

found: Oxford DNB : (FitzGerald, Thomas Joseph (Desmond), b. London 13 Feb. 1888, d. Dublin 9 Apr. 1947)

found: LC database, 23 May 2006, Memoirs of Desmond FitzGerald, 1913-1916, 1968 : (hdg.: FitzGerald, Desmond, 1889-1947)

FitzGerald, Thomas Joseph [Desmond] (1888–1947), politician in Ireland, was born at 62 Arthingworth Street, West Ham, London, on 13 February 1888, of Irish parents, the sixth child and fourth son of Patrick FitzGerald (d. 1908), stonemason and builder, of Castleisland, co. Kerry, and his wife, Mary Anne (d. 1927), daughter of William Scollard and his wife, Margaret, also of Castleisland. Brought up in London, Tommy FitzGerald adopted the romantic name Desmond (the name of the rulers of the Munster of his ancestors) in his late teens, when he had become a member of the imagist group of young London poets. On leaving school he took a job as a clerk and began to learn Irish. It was at a class of the Gaelic League that he met Mabel Washington McConnell (1884/5–1958), a graduate of Ireland's Royal University (through Queen's College, Belfast), then studying for her teaching qualification and doing part-time secretarial work for, among others, George Bernard Shaw.

They married on 13 May 1911 and moved to Brittany, living mainly at St Jean-du-Doigt, near Morlaix, where their first child, Desmond Patrick Jean-Marie, was born. In February 1913 they moved to Ireland, alerted to the nationalist stirrings (though Mabel was from a protestant, unionist background, she had already taken up the nationalist cause before meeting her nationalist, Roman Catholic husband). They took up residence in Irish-speaking co. Kerry, at Ventry Harbour, immersed themselves in the Irish language, and met up with other enthusiasts including Ernest Blythe, a future political colleague. Desmond joined the newly formed Irish Volunteers in November 1913, and he and Blythe recruited others to the cause, adhering to the rump volunteer grouping when the movement split on the outbreak of the First World War. By then a second son, Pierce, had been born (March 1914). Two further sons would complete the family: Fergus in February 1920, and Garret, a future taoiseach, in February 1926.

Expelled from co. Kerry in January 1915 on suspicion of signalling to German submarines, FitzGerald took his family to Bray, 12 miles south of Dublin, and soon busied himself organizing the volunteers in co. Wicklow. He spent six months in gaol that year for speaking against recruitment to the British army. At Easter 1916 he and his wife both found themselves in the General Post Office in Dublin, participating in a rising that he, for one, assumed would lead to his death. Mabel was sent home during that fateful week to look after her young family. Desmond survived but was sentenced to twenty years' penal servitude (later commuted to ten years), and experienced a variety of prisons in Ireland and England before being released in mid-1917. He endured a further ten months' imprisonment from May 1918 until March 1919. By then he had been elected to Westminster for the Pembroke division of Dublin in the 1918 general election, though as a Sinn Féin abstentionist he chose to sit in Dáil Éireann rather than the London parliament.

In the ensuing Anglo-Irish War, Desmond FitzGerald played a leading role as substitute director of propaganda for the Dáil government, from April 1919. He launched the underground Irish Bulletin in November 1919 and used his London connections to make contact with foreign journalists. His fluent French and his literary interests enabled him to ensure that the Irish case was successfully advanced in Europe and America. He was to carry on this responsibility, from January 1922, as minister for publicity outside the cabinet of the new Irish government. In September 1922 he entered the cabinet as minister for external affairs, holding this post until 1927, when he became minister for defence.

Desmond FitzGerald was thus one of the principal founders of the Irish Free State. He was described at the time by a visiting French journalist: ‘fair hair floating around a high forehead his appearance was of a noble, ardent and daring delicateness; and in his blue eyes shone simultaneously gaiety, tenderness, courage and poetry’ (Joseph Kessel, Témoin parmi les hommes, 1956, quoted in F. FitzGerald, xii). Later a colleague looked back to recall ‘a slight, delicate-looking young man with curly reddish hair and an aesthetic mien’ (Nichevo, ‘An Irishman's diary’, Irish Times, 12 April 1947). He was an intellectual revolutionary of literary and linguistic interests, with an enthusiasm for philosophy that was to stand him in good stead later.

It was FitzGerald, as minister for external affairs, who made Ireland's formal application to join the League of Nations in April 1923, seeing it admitted that September. He championed the small nation members there and laid the foundation for Ireland's election to the council in 1930. He also pioneered Ireland's role within the emerging British Commonwealth of Nations, attending, with Eoin MacNeill, the 1923 Imperial Conference. He was surprised at the trust shown the Irish Free State at this meeting, which thrust him to the centre of the empire's establishment. In time he was to gain appreciation of this organization of ‘sister’ nations in a troubled post-war world, though the free state was to remain a restless member throughout the period of its involvement.

It was important to the young state to demonstrate its independence from Britain, and FitzGerald made 1924 a landmark year by registering the Anglo-Irish treaty at the League of Nations (against British wishes, as it was deemed by London to be an inter-imperial and not a fully international agreement), by sending the first dominion envoy abroad (to Washington), and by refusing to be bound by parts of the 1923 Lausanne treaty when its ratification became due, as the free state had not been involved in its negotiation. He continued to take an independent stance at the League of Nations, and also used the 1926 Imperial Conference to assert further the equality and autonomy of the dominions. Later his experience was harnessed at the 1930 Imperial Conference, as the preparations were completed for the 1931 Statute of Westminster, which gave final legal recognition to dominion sovereignty.

Law and order remained a central preoccupation in the new state, after a civil war, after a threatened army mutiny in 1924, and with a continuing pattern of unorthodox and violent groups settling scores, ill restrained by an unarmed police force. The Ministry of Defence needed clear leadership and a strong will. This FitzGerald supplied, and from his appointment in June 1927 to February 1932, when the founding government was defeated in a general election, he oversaw the reduction in army numbers and an increase in discipline and effectiveness, so that the government's authority could be upheld in deteriorating economic and security circumstances, and the democratic process protected. This, however, led to clashes with senior officers and brought about Seán MacEoin's removal as chief of staff in 1929.

Out of office from 1932 FitzGerald remained a TD, moving from co. Dublin (which he had represented since 1922) to Carlow–Kilkenny, from 1932 to 1937 when he lost his seat. In 1938 he was elected to the Seanad, on the administrative panel, but was defeated in 1943 and, after failing to win back his old co. Dublin seat in 1944, he retired from politics. His record in the Seanad was deemed undistinguished, his concerns being too academic and philosophical. He had already become something of an expert Thomist, and he delivered courses in philosophy at Notre Dame University, Indiana, as a visiting professor, during parts of the year, from 1935 to 1938. The lectures formed the first four chapters of his Preface to Statecraft (1939) and the appointments helped to eke out his small ministerial pension. His fragment of autobiography, Memoirs of Desmond FitzGerald, covering the years 1913–16 and containing a good photographic portrait, did not appear until 1968, edited by his son Fergus, but his two-scene play, The Saint, had been produced by Lennox Robinson at the Abbey Theatre in September 1919.

An intellectual who lacked the common touch, a raconteur possessed of a superb memory, and a man of great physical and moral courage, FitzGerald mixed with literary figures, poets such as Pound, Eliot, and Yeats, the French philosopher Maritain, and the Irish cultural élite in general. His friendships traversed the political divide, and his honesty of purpose was respected by all sections. Although he had suffered from angina there was widespread shock at his sudden death from a heart attack at his home, Airfield, Donnybrook, Dublin, on 9 April 1947. His funeral, at the church of the Sacred Heart, Donnybrook, was attended by President O'Kelly and Taoiseach de Valera, political opponents, and by Britain's representative in Ireland, Sir John Maffey. He was buried in Glasnevin cemetery two days later. His wife survived him.

David Harkness

Sources

G. FitzGerald, All in a life: an autobiography (1991) · F. FitzGerald, ed., Memoirs of Desmond FitzGerald (1968) · D. Macardle, The Irish republic (1937) · D. W. Harkness, The restless dominion (1969) · M. Kennedy, Ireland and the League of Nations, 1919–46 (1996) · Irish Times (10 April 1947) · Nichevo, ‘An Irishman's diary’, Irish Times (12 April 1947) · Irish Times (14 April 1947) · Dáil Éireann: parliamentary debates (1919–37) [1st–8th Dáil] · b. cert. · m. cert.

Archives

University College, Dublin, MSS, P80

Likenesses

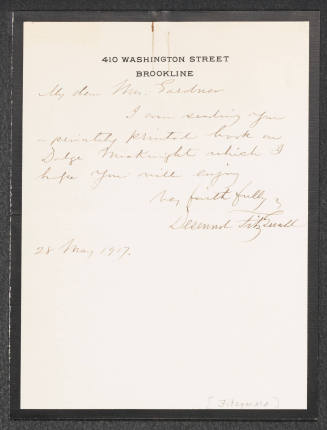

photograph, repro. in FitzGerald, ed., Memoirs

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

David Harkness, ‘FitzGerald, Thomas Joseph (1888–1947)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/52590, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Thomas Joseph FitzGerald (1888–1947): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52590